Alcohol vs. Cocaine: Impulsivity and Alexithymia in Substance Use Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Sample Characteristics

2.2. Psychometric Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Differences

3.2. Psychological and Clinical Measures

3.3. CUD-Only vs. Poly-Substance Use Comparison

3.4. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achab, S., Nicolier, M., Masse, C., Vandel, P., Bennabi, D., Mauny, F., & Haffen, E. (2013). Alexithymia and impulsivity as common features in addictive disorders. Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy, 4(3), 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D. A., & Taylor, G. J. (1994). The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38(1), 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, E. S. (1985). Impulsiveness subtraits: Arousal and information processing. In J. T. Spence, & C. E. Izard (Eds.), Motivation, emotion, and personality (pp. 137–146). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Boden, J. M., & Fergusson, D. M. (2011). Alcohol and depression: Causation, mechanisms, and treatment. Alcohol Research & Health, 34(2), 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Bressi, C., Taylor, G., Parker, J., Bressi, S., Brambilla, V., Aguglia, E., Allegranti, I., Bongiorno, A., Giberti, F., Bucca, M., Todarello, O., Callegari, C., Vender, S., Gala, C., & Invernizzi, G. (1996). Cross validation of the factor structure of the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: An Italian multicenter study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 41(6), 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T. A., Avery, J. C., Jones, M. D., Anderson, L. K., Wierenga, C. E., & Kaye, W. H. (2018). The impact of alexithymia on emotion dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa over time. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(2), 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centanni, S. W., Morris, B. D., Luchsinger, J. R., Bedse, G., Fetterly, T. L., Patel, S., & Winder, D. G. (2020). Endocannabinoid control of the insular–amygdalar circuit regulates alcohol intake. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 14, 580849. [Google Scholar]

- Chaim, C. H., Almeida, T. M., de Vries Albertin, P., Santana, G. L., Siu, E. R., & Andrade, L. H. (2024). The implication of alexithymia in personality disorders: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craparo, G., Gori, A., Iraci Sareri, G., & Caretti, V. (2014). Antisocial and psychopathic personalities in a sample of addicted subjects: Differences in psychological resources, symptoms, alexithymia, and impulsivity. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(7), 1580–1586. [Google Scholar]

- Crews, F. T., Vetreno, R. P., Broadwater, M. A., & Robinson, D. L. (2016). Adolescence, alcohol, and the developing brain: Insights from studies in humans and animal models. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 38(2), 255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Dalley, J. W., & Ersche, K. D. (2019). Neural circuitry and mechanisms of waiting impulsivity: Relevance to addiction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences, 374, 20180145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EMCDDA. (2022). EMCDDA operating guidelines for the European Union Early Warning System on new psychoactive substances. EMCDDA. [Google Scholar]

- Evren, C., Cınar, O., Evren, B., & Celik, S. (2012). Relationship between defense styles, alexithymia, and personality in alcohol-dependent inpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53(6), 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evren, C., Evren, B., Dalbudak, E., & Cakmak, D. (2008). Alexithymia and personality in relation to social anxiety among male alcohol-dependent inpatients. Archives of Neuropsychiatry, 45(3), 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Fossati, A., Di Ceglie, A., Acquarini, E., & Barratt, E. S. (2001). Psychometric properties of an Italian version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11) in nonclinical subjects. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(6), 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giustiniani, J., Nicolier, M., Pascard, M., Masse, C., Vandel, P., Bennabi, D., Achab, S., Mauny, F., & Haffen, E. (2022). Do individuals with internet gaming disorders share personality traits with substance-dependent individuals? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 9536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A., Craparo, G., & Caretti, V. (2014). Psychological characteristics of addicts with psychopathic and antisocial tendencies. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55(7), 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, K. A., & Witkiewitz, K. (2015). Depression as a mediator of alcohol treatment outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(1), 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Leeman, R. F., & Potenza, M. N. (2014). Similarities and differences between pathological gambling and substance use disorders: A focus on impulsivity and compulsivity. Psychopharmacology, 231(19), 4251–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loree, A. M., Lundahl, L. H., & Ledgerwood, D. M. (2015). Impulsivity as a predictor of treatment outcome in substance use disorders: Review and synthesis. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34(2), 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaker, P. H., Davis, L. W., Hunter, N. L., Nees, M. A., & Wickett, A. (2005). Alexithymia and schizophrenia: Associations with symptoms, neurocognition, and social function. Psychiatry Research, 135(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Martinotti, G., Di Nicola, M., Tedeschi, D., Cundari, S., & Janiri, L. (2009). Empathy ability is impaired in alcohol-dependent patients. The American Journal on Addictions, 18(2), 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, R. K., & Weiss, R. D. (2019). Alcohol use disorder and depressive disorders. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 40(1), arcr-v40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosca, A., Miuli, A., Mancusi, G., Chiappini, S., Stigliano, G., De Pasquale, A., Di Petta, G., Bubbico, G., Pasino, A., Pettorruso, M., & Martinotti, G. (2023). To bridge or not to bridge: Moral judgement in cocaine use disorders, a case-control study on human morality. Social Neuroscience, 18(5), 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, S., Haddad, C., Fares, K., Malaeb, D., Sacre, H., Akel, M., Salameh, P., & Hallit, S. (2021). Correlates of emotional intelligence among Lebanese adults: The role of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, alcohol use disorder, alexithymia and work fatigue. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma-Álvarez, R. F., Ros-Cucurull, E., Daigre, C., Perea-Ortueta, M., Serrano-Pérez, P., Martínez-Luna, N., Salas-Martínez, A., Robles-Martínez, M., Ramos-Quiroga, J. A., Roncero, C., & Grau-López, L. (2021). Alexithymia in patients with substance use disorders and its relationship with psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 659063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S. C., Ugale, R., Zhang, H., Tang, L., & Prakash, A. (2008). Brain chromatin remodeling: A novel mechanism of alcoholism. Journal of Neuroscience, 28(14), 3729–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepe, M., Di Nicola, M., Panaccione, I., Franza, R., De Berardis, D., Cibin, M., Janiri, L., & Sani, G. (2023). Impulsivity and alexithymia predict early versus subsequent relapse in patients with alcohol use disorder: A 1-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Review, 42(2), 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadock, B. J., & Sadock, V. A. (2009). Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Saeedi Rashkolia, A., Manzari Tavakoli, A., Zeinaddiny Meymand, Z., & Hosseini Fard, S. M. (2022). The effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy on alexithymia, emotion regulation, and psychological capital of male substance abusers treated by addiction treatment centers in Kerman. Addict Health, 14(2), 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffers, J., Völlm, B. A., Rücker, G., Timmer, A., Huband, N., & Lieb, K. (2010). Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6, CD005653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G. J., Bagby, R. M., & Parker, J. D. (1997). Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thorberg, F. A., Young, R. M., Sullivan, K. A., & Lyvers, M. (2009). Alexithymia and alcohol use disorders: A critical review. Addictive Behaviors, 34(3), 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2023). World Drug Report 2023. United Nations. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2023.html (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Urueña-Méndez, G., Dimiziani, A., Belles, L., Goutaudier, R., & Ginovart, N. (2023). Repeated cocaine intake differentially impacts striatal D(2/3) receptor availability, psychostimulant-induced dopamine release, and trait behavioral markers of drug abuse. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(17), 13238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van’t Wout, M., Aleman, A., Bermond, B., & Kahn, R. S. (2007). No words for feelings: Alexithymia in schizophrenia patients and first-degree relatives. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48(1), 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, J., Green, M. F., Shaner, A., & Liberman, R. P. (1993). Training and quality assurance with the brief psychiatric rating scale: “The drift busters”. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 3(4), 221–244. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2018). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274603 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Zargar, F., Bagheri, N., Tarrahi, M. J., & Salehi, M. (2019). Effectiveness of emotion regulation group therapy on craving, emotion problems, and marital satisfaction in patients with substance use disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 14(4), 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberman, N., Yadid, G., Efrati, Y., & Rassovsky, Y. (2020). Who becomes addicted and to what? psychosocial predictors of substance and behavioral addictive disorders. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziółkowski, M., Gruss, T., & Rybakowski, J. K. (1995). Does alexithymia in male alcoholics constitute a negative factor for maintaining abstinence? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 63(3–4), 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizzi, A., Berri, I. M., Occhipinti, M., Escelsior, A., & Serafini, G. (2024). Psychological dimensions in alcohol use disorder: Comparing active drinkers and abstinent patients. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1420508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex (Alc) | Sex (Coca) | Age (Alc) | Age (Coca) | Educyears (Alc) | Educyears (Coca) | Employed (Alc) | Employed (Coca) | Marital Status (Alc) | Marital Status (Coca) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 39.0 | 80.00 | 39.00 | 80.00 | 39.000 | 80.000 | 39.000 | 80.000 | 39.00 | 80.00 |

| Mean | 0.25 | 0.900 | 52.41 | 38.36 | 11.949 | 12.650 | 0.385 | 0.700 | 1.077 | 0.650 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.44 | 0.302 | 10.20 | 7.818 | 3.839 | 3.691 | 0.493 | 0.461 | 0.900 | 0.597 |

| Minimum | 0.00 | 0.000 | 30.0 | 19.00 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Maximum | 1.00 | 1.000 | 74.0 | 57.00 | 18.000 | 25.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 3.000 | 2.000 |

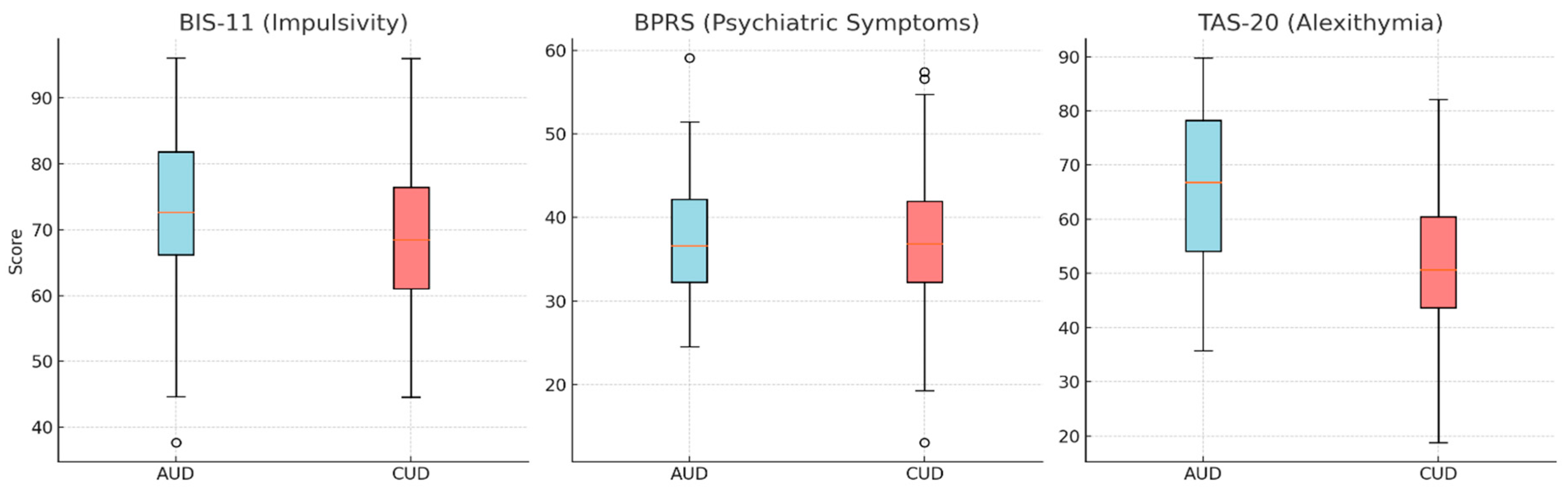

| BIS-11 (Alc) | BIS-11 (Coca) | BPRS (Alc) | BPRS (Coca) | TAS-20 (Alc) | TAS-20 (Coca) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | 39 | 80 | 39 | 80 | 39 | 80 |

| Mean | 68.590 | 69.400 | 40.744 | 37.513 | 59.615 | 52.737 |

| SD | 12.115 | 11.170 | 9.397 | 8.812 | 15.508 | 12.758 |

| Minimum | 45.000 | 37.000 | 24.000 | 20.000 | 21.000 | 25.000 |

| Maximum | 92.000 | 92.000 | 61.000 | 59.000 | 92.000 | 89.000 |

| Predictor | β (Coef.) | Std. Error | z-Value | p-Value | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.025 | 0.028 | 0.909 | 0.364 | −0.029 | 0.079 |

| Education (years) | 0.075 | 0.074 | 1.014 | 0.312 | −0.070 | 0.219 |

| BIS-11 (impulsivity) | −0.019 | 0.029 | −0.669 | 0.505 | −0.075 | 0.037 |

| BPRS (Psych. Syntoms) | 0.062 | 0.038 | 1.616 | 0.106 | −0.013 | 0.137 |

| TAS-20 (Alexithymia) | 0.045 | 0.025 | 1.814 | 0.070 | −0.004 | 0.093 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mosca, A.; Bubbico, G.; Cavallotto, C.; Chiappini, S.; Allegretti, R.; Miuli, A.; Marrangone, C.; Ciraselli, N.; Pettorruso, M.; Martinotti, G. Alcohol vs. Cocaine: Impulsivity and Alexithymia in Substance Use Disorder. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 711. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060711

Mosca A, Bubbico G, Cavallotto C, Chiappini S, Allegretti R, Miuli A, Marrangone C, Ciraselli N, Pettorruso M, Martinotti G. Alcohol vs. Cocaine: Impulsivity and Alexithymia in Substance Use Disorder. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):711. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060711

Chicago/Turabian StyleMosca, Alessio, Giovanna Bubbico, Clara Cavallotto, Stefania Chiappini, Rita Allegretti, Andrea Miuli, Carlotta Marrangone, Nicola Ciraselli, Mauro Pettorruso, and Giovanni Martinotti. 2025. "Alcohol vs. Cocaine: Impulsivity and Alexithymia in Substance Use Disorder" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 711. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060711

APA StyleMosca, A., Bubbico, G., Cavallotto, C., Chiappini, S., Allegretti, R., Miuli, A., Marrangone, C., Ciraselli, N., Pettorruso, M., & Martinotti, G. (2025). Alcohol vs. Cocaine: Impulsivity and Alexithymia in Substance Use Disorder. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 711. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060711