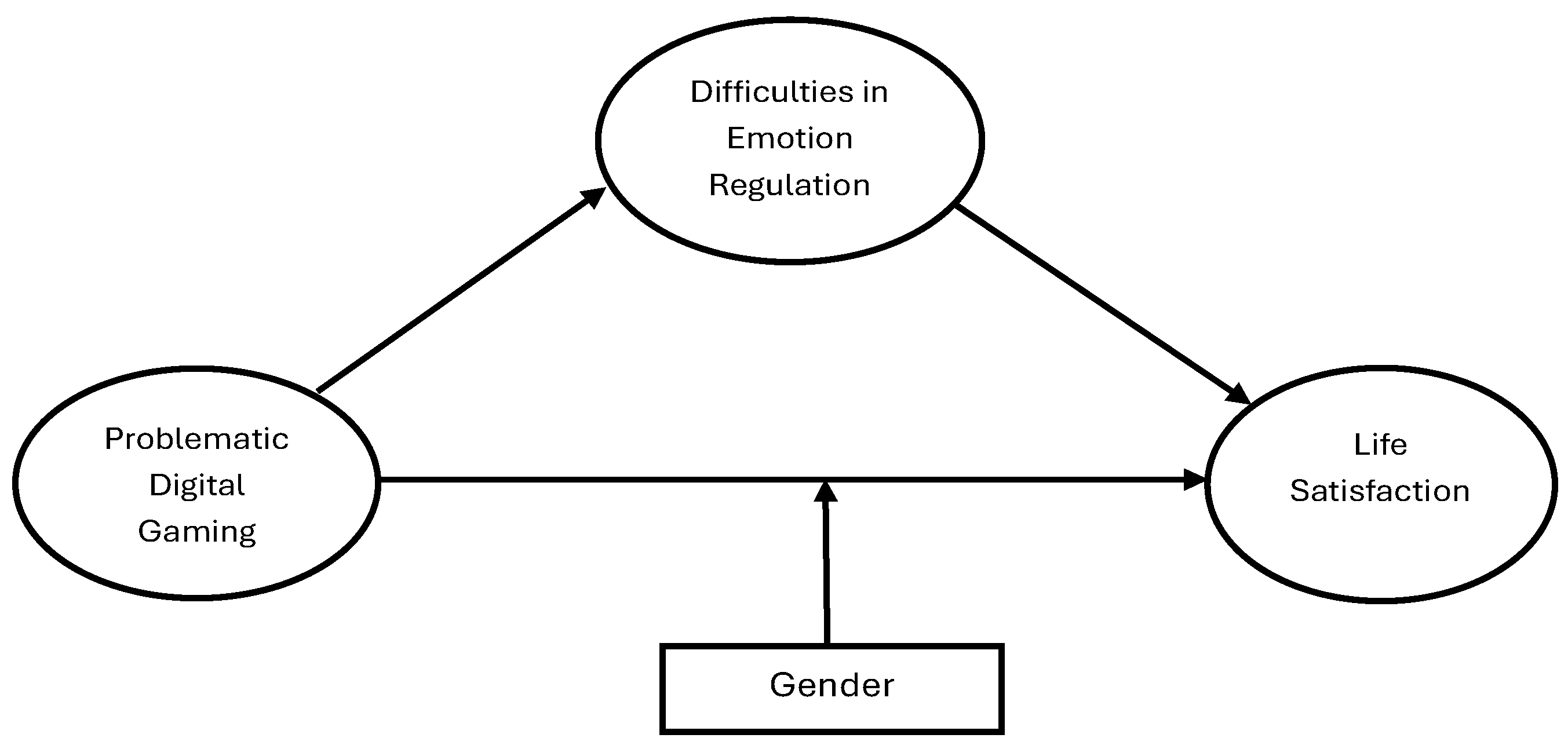

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation as a Mediator and Gender as a Moderator in the Relationship Between Problematic Digital Gaming and Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Problematic Digital Gaming and Life Satisfaction

2.2. The Mediating Role of Difficulties in Emotion Regulation

2.3. The Moderating Role of Gender

2.4. Present Study

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

4.2. Testing for Moderated Mediation

5. Discussion

5.1. The Relationship Between Problematic Digital Gaming and Life Satisfaction

5.2. The Mediating Role of Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Between Problematic Digital Gaming and Life Satisfaction

5.3. The Moderating Role of Gender

5.4. Contribution and Limitations

5.5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akeren, İ., Çelik, E., Yayla, İ. E., & Özgöl, M. (2025). The effect of self-regulation on the need for psychological help through happiness, resilience, problem solving, self-efficacy, and adjustment: A parallel mediation study in adolescent groups. Children, 12(4), 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.; DSM-5-TR). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anlı, G., & Taş, İ. (2018). The validity and reliability of the game addiction scale for adolescents-short form. Electronic Turkish Studies, 13(11), 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayllón-Salas, P., & Fernández-Martín, F. D. (2024). The role of social and emotional skills on adolescents’ life satisfaction and academic performance. Psychology, Society & Education, 16(1), 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, D. (2021). An investigation of the relationships between digital game addiction, behavioral-emotional problems, and negative cognitive errors in middle school students [Master’s thesis, Dokuz Eylul University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2925388854). Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/ortaokul-öğrencilerinde-dijital-oyun-bağımlılığı/docview/2925388854/se-2 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Azpiazu Izaguirre, L., Fernández, A. R., & Palacios, E. G. (2021). Adolescent life satisfaction explained by social support, emotion regulation, and resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 694183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basyouni, S. S., & Keshky, M. E. S. E. (2021). The role of emotion regulation in the relation between anxiety and life satisfaction among Saudi children and adolescents. Journal of Psychology & Clinical Psychiatry, 12(2), 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussone, S., Trentini, C., Tambelli, R., & Carola, V. (2020). Early-life interpersonal and affective risk factors for pathological gaming. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canale, N., Elgar, F. J., Pivetta, E., Galeotti, T., Marino, C., Billieux, J., King, D. L., Lenzi, M., Dalmasso, P., Lazzeri, G., Nardone, P., Camporese, A., & Vieno, A. (2025). Problem gaming and adolescents’ health and well-being: Evidence from a large nationally representative sample in Italy. Computers in Human Behavior, 168, 108644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C. B., Cabral, J. M., Teixeira, M., Cordeiro, F., Costa, R., & Arroz, A. M. (2023). “Belonging without being”: Relationships between problematic gaming, internet use, and social group attachment in adolescence. Computers in Human Behavior, 149, 107932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C. M., & Neto, D. D. (2025). From healthy play to gaming disorder: Psychological profiles from emotional regulation and motivational factors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 14(1), 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Calvo, J., King, D. L., Stein, D. J., Brand, M., Carmi, L., Chamberlain, S. R., Demetrovics, Z., Fineberg, N. A., Rumpf, H.-J., Yücel, M., Achab, S., Ambekar, A., Bahar, N., Blaszczynski, A., Bowden-Jones, H., Carbonell, X., Chan, E. M. L., Ko, C.-H., de Timary, P., … Billieux, J. (2021). Expert appraisal of criteria for assessing gaming disorder: An international Delphi study. Addiction, 116(9), 2463–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavioni, V., Grazzani, I., Ornaghi, V., Agliati, A., & Pepe, A. (2021). Adolescents’ mental health at school: The mediating role of life satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 720628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamarro, A., Díaz-Moreno, A., Bonilla, I., Cladellas, R., Griffiths, M. D., Gómez-Romero, M. J., & Limonero, J. T. (2024). Stress and suicide risk among adolescents: The role of problematic internet use, gaming disorder and emotional regulation. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T. M., & Aldao, A. (2013). Gender differences in emotion expression in children: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 139(4), 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, S., Wong, H. K., Chen, Y., Zhang, S., & Li, C. S. R. (2024). Sex differences in the effects of individual anxiety state on regional responses to negative emotional scenes. Biology of Sex Differences, 15(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Mokhtar, M., & McGee, R. (2025). Impact of internet addiction and gaming disorder on body weight in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 61(2), 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H. J., Lee, T. S. H., & Wu, W. C. (2025). The influence of children’s emotional regulation on internet addiction during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of depression. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, S. C., Chen, W. C., & Wu, P. Y. (2023). Daily association between parent−adolescent relationship and life satisfaction: The moderating role of emotion dysregulation. Journal of Adolescence, 95(6), 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, C., Lansing, A. H., & Houck, C. D. (2022). Perceived strengths and difficulties in emotional awareness and accessing emotion regulation strategies in early adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(9), 2631–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çan, G., Günüç, S., Topbaş, M., Beyhun, N. E., Şahin, K., & Somuncu, B. P. (2021). The examining of ınternet addiction and its related factors in children aged 6–18 years. Sakarya Medical Journal, 11(2), 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, E., & Ertürk, K. (2022). The effect of forgiveness psychoeducation on forgiveness and life satisfaction in high school students. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(1), 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelikkaleli, Ö., Ata, R., Alpaslan, M. M., Tangülü, Z., & Ulubey, Ö. (2025). Examining the roles of problematic internet use and emotional regulation self-efficacy on the relationship between digital game addiction and motivation among turkish adolescents. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dağlı, A., & Baysal, N. (2016). Adaptation of the satisfaction with life scale into Turkish: The study of validity and reliability. Electronic Journal of Social Sciences, 15(59). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, Y. (2024). Çocukların dijital oyun bağımlılıklarının incelenmesi. Muallim Rıfat Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 6(1), 24–42. [Google Scholar]

- Deniz, M. E., Kurtulus, H. Y., & Kaya, Y. (2024). Family communication and bi-dimensional student mental health in adolescents: A serial mediation through digital game addiction and school belongingness. Psychology in the Schools, 61(11), 4375–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezhapoun, M. (2025). The relatıonshıp between lıfe satısfactıon and mental health of adolescents. TMP Universal Journal of Research and Review Archives, 4(1), 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Plinio, S. (2025). Panta Rh-AI: Assessing multifaceted AI threats on human agency and identity. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 11, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, H., & Tas, I. (2022). The relationship between game addiction, emotional autonomy and emotion regulation in adolescents: A multiple mediation model. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science, 6(4), 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekşi, H., & Erik, C. (2023, July 20–21). Difficulties in emotion regulation scale-8: Adaptation to Turkish [Paper Presentation]. 2st International Congress of Educational Sciences and Linguists, Warsaw, Poland. Available online: https://www.icssietcongress.com/_files/ugd/2a6f60_a246f8a809bd4a9dbb739a725c8cc4a4.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Ercengiz, M., & Şar, A. H. (2017). The role to predict the internet addiction of emotion regulation in adolescents. Sakarya University Journal of Education, 7(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdian, A., & Hidayat, D. (2024). Life satisfaction in adolescents: A systematic literature review. Bisma The Journal of Counseling, 8(1), 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, C., & Gordon, I. (2025). The imperfect yet valuable difficulties in emotion regulation scale: Factor structure, dimensionality, and possible cutoff score. Assessment, 32(5), 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, A., Jáuregui, P., Sánchez-Marcos, I., López-González, H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Attachment and emotion regulation in substance addictions and behavioral addictions. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estupiñá, F. J., Bernaldo-de-Quirós, M., Vallejo-Achón, M., Fernández-Arias, I., & Labrador, F. (2024). Emotional regulation in gaming disorder: A systematic review. The American Journal on Addictions, 33(6), 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenkrog, S., Rittmann, L. M., Klüpfel, L., Delfs, S., & Stumm, J. (2025). Media addiction in children and adolescents—A study protocol for development, piloting and evaluation of a sustainable, integrative rehabilitation program (MeKi). Frontiers in Adolescent Medicine, 3, 1524971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, I., & Gorriz, A. (2024). The Self-esteem, emotional regulation, and their relationship with the risk of self-harm and physical and emotional well-being in adolescents. Calidad De Vida Y Salud, 17(2), 2–17. Available online: https://revistacdvs.uflo.edu.ar/index.php/CdVUFLO/article/view/437 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Filipovič, V., Dědová, M., & Mihaliková, V. (2023). Relationships of school climate, parental support, life satisfaction, and internet gaming disorder among adolescents. Journal of Educational Sciences & Psychology, 13(2), 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetan, S., Bonnet, A., & Pedinielli, J. L. (2012). Self-perception and life satisfaction in video game addiction in young adolescents (11–14 years old). L’Encéphale, 38(6), 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geniş, Ç., & Ayaz-Alkaya, S. (2023). Digital game addiction, social anxiety, and parental attitudes in adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Children and Youth Services Review, 149, 106931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardina, A., Schimmenti, A., Starcevic, V., King, D. L., Di Blasi, M., & Billieux, J. (2024). Problematic gaming, social withdrawal, and escapism: The Compensatory-Dissociative Online Gaming (C-DOG) model. Computers in Human Behavior, 155, 108187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A. L., Schmit, M. K., & McCall, J. (2023). Exploring adolescent social media and internet gaming addiction: The role of emotion regulation. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, 44(1), 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M., Rovella, A., Barrera, A., & González, M. (2023). Relationships of emotion regulation to procrastination, life satisfaction and resilience to discomfort. Interacciones, 9, e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, S., Zhang, W., Tang, Y., Zhang, J., & He, Q. (2024). Prevalence of internet gaming disorder among Chinese adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 102, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Leal, R., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Faria, L., Costa, A., & Cabello, R. (2024). The role of emotional intelligence and gender in the relationship between implicit theories of emotions and aggression: Moderated mediation model in young individuals. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1), 2363352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-León, M. I. (2025). Serious games to support emotional regulation strategies in educational intervention programs with children and adolescents. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon, 11(4), e42712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, W. L. (2023). A review on the evaluation of video game addiction as a legitimate disorder. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 11(3), 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H. C., & Kao, S. F. (2021). The relationship between internet addiction, game addiction, and life satisfaction in high school students: Parents’ attitude toward their children’s online behavior as a moderating variable. Journal of Research in Education Sciences, 66(4), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollett, K. B., & Harris, N. (2020). Dimensions of emotion dysregulation associated with problem video gaming. Addiction Research & Theory, 28(1), 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008, June 19–20). Evaluating model ft: A synthesis of the structural equation modelling literature. 7th European Conference on Research Methodology for Business and Management Studies (pp. 195–200), London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S., Jeong, E. J., & Kim, J. (2023). Effects of problematic game use on adolescent life satisfaction through social support and materialism. Social Integration Research, 4(2), 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Ren, Y., Zhu, J., & You, J. (2022). Gratitude and hope relate to adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: Mediation through self-compassion and family and school experiences. Current Psychology, 41(2), 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartol, A., Üztemur, S., Griffiths, M. D., & Şahin, D. (2024). Exploring the interplay of emotional intelligence, psychological resilience, perceived stress, and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study in the Turkish context. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A., Türk, N., Batmaz, H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2024). Online gaming addiction and basic psychological needs among adolescents: The mediating roles of meaning in life and responsibility. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 22(4), 2413–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekkonen, V., Tolmunen, T., Kraav, S. L., Hintikka, J., Kivimäki, P., Kaarre, O., & Laukkanen, E. (2020). Adolescents’ peer contacts promote life satisfaction in young adulthood—A connection mediated by the subjective experience of not being lonely. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, 110264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircaburun, K., Alhabash, S., Tosuntaş, Ş. B., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: A simultaneous examination of the Big Five of personality traits, social media platforms, and social media use motives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabas, S., Adak, I., Karakus, O. B., & Toksoy, Z. E. (2025). Learning disability as a determinant of digital behavior in adolescents with ADHD: A cross-sectional study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükturan, A. G., Horzum, M. B., Korkmaz, G., & Üngören, Y. (2022). Investigating the relationship between personality, chronotype, computer game addiction, and sleep quality of high school students: A structural equation modelling approach. Chronobiology International, 39(4), 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L., Zhu, M., Dai, J., Li, M., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The mediating roles of emotional regulation on negative emotion and internet addiction among Chinese adolescents from a development perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 608317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Z., Le, J., Chen, X., Tang, Y., Shen, H., & Huang, Q. (2025). Gender differences in problematic gaming among Chinese adolescents and young adults. BMC Psychiatry, 25(1), 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P. Y., Lin, H. C., Lin, P. C., Yen, J. Y., & Ko, C. H. (2020). The association between emotional regulation and internet gaming disorder. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, B., O’Brien, J. M., Peña, P. A., Galla, B. M., D’Mello, S., Yeager, D. S., Defnet, A., Kautz, T., Munkacsy, K., & Duckworth, A. L. (2022). Large studies reveal how reference bias limits policy applications of self-report measures. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 19189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., Mo, B., Yang, P., Li, D., Liu, S., & Cai, D. (2023). Values mediated emotional adjustment by emotion regulation: A longitudinal study among adolescents in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1093072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z., Sun, X., Guo, Y., & Yang, S. (2021). Mindful parenting is positively associated with adolescents’ life satisfaction: The mediating role of adolescents’ coping self-efficacy. Current Psychology, 42(19), 16070–16081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudoun, F. M., Larsson-Lund, M., Boyle, B., & Nyman, A. (2024). The process of negotiating and balancing digital play in everyday life: Adolescents’ narratives. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31(1), 2435922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Moosbrugger, M., Smith, D. M., France, T. J., Ma, J., & Xiao, J. (2022). Is increased video game participation associated with reduced sense of loneliness? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 898338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahamid, F. A., & Bdier, D. (2021). Aggressiveness and life satisfaction as predictors for video game addiction among Palestinian adolescents. Journal of Concurrent Disorders, 3(2), 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheux, A. J., Garrett, S. L., Fox, K. A., Field, N. H., Burnell, K., Telzer, E. H., & Prinstein, M. J. (2025). Adolescent social gaming as a form of social media: A call for developmental science. Child Development Perspectives, 19(1), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makas, S., & Koç, M. (2025). The mediating effect of emotional schemas in the relationship between online gaming addiction and life satisfaction. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, N., Mullick, T., Mazumdar, S., & Das, S. (2023). A study on self-esteem and life satisfaction among adolescents aged 14–19 years attending adolescent-friendly health clinic, Medical College, Kolkata. National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 13(11), 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroney, N., Williams, B. J., Thomas, A., Skues, J., & Moulding, R. (2019). A stress-coping model of problem online video game use. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., & Hau, K. T. (1996). Assessing goodness of fit: Is parsimony always desirable? The Journal of Experimental Education, 64(4), 364–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J., Koenig, J., Nashiro, K., Yoo, H. J., Cho, C., Thayer, J. F., & Mather, M. (2023). Sex differences in neural correlates of emotion regulation in relation to resting heart rate variability. Brain Topography, 36(5), 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miniksar, D. Y., & Kılıç, M. (2023). The relationship between attachment styles and emotion regulation difficulties in adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Sakarya Medical Journal, 13(2), 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R. (2020). Emotional regulation and life satisfaction among housewives. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 8(3), 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaeipour, L., Jabarbeigi, R., Lari, T., Osooli, M., & Jafari, E. (2025). Gaming disorder and psychological distress among Iranian adolescents: The mediating role of sleep hygiene. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T., & Bonnaire, C. (2021). Intrapersonal and interpersonal emotion regulation and identity: A preliminary study of avatar identification and gaming in adolescents and young adults. Psychiatry Research, 295, 113627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J. M., Chu, J., Zamora, G., Ganson, K. T., Testa, A., Jackson, D. B., Costello, C. R., Murray, S. B., & Baker, F. C. (2023). Screen time and obsessive-compulsive disorder among children 9–10 years old: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 72(3), 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, A., Gul, M., & Niazi, Y. (2024). The association between loneliness, social anxiety, and gaming addiction in male university students. Bulletin of Business and Economics (BBE), 13(1), 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y., Wang, T., Guo, M., Zhou, F., Ma, W., Qiu, W., Gao, J., & Liu, C. (2025). The relationship between physical activity, life satisfaction, emotional regulation, and physical self esteem among college students. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 15899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira-López, A., Rial-Boubeta, A., Guadix-García, I., Villanueva-Blasco, V. J., & Billieux, J. (2023). Prevalence of problematic Internet use and problematic gaming in Spanish adolescents. Psychiatry Research, 326, 115317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurmagandi, B., & Suratmini, D. (2024). The correlation between depression with online game addiction among adolescents: Systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 15(1), 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogelman, H. G., & Kahveci, D. (2024). Examining the effect of preschool children’s resilience on emotion regulation skills. Sakarya University Journal of Education Faculty, 24(1), 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, S., & Özekes, M. (2020). Relationship between basic psychological needs and problematic internet use of adolescents: The mediating role of life satisfaction. ADDICTA: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 7(4), 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavicini, F., Pepe, A., & Mantovani, F. (2022). The effects of playing video games on stress, anxiety, depression, loneliness, and gaming disorder during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: PRISMA systematic review. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(6), 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, F., Steinberg, L., & Sharp, C. (2022). The development and validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale-8: Providing respondents with a uniform context that elicits thinking about situations requiring emotion regulation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 105(5), 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, A., & Topal, M. (2022). Relationship between digital game addiction with body mass index, academic achievement, player types, gaming time: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 5(4), 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, E., Vijayakumar, N., Rakesh, D., & Whittle, S. (2021). Neural correlates of emotion regulation in adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analytic study. Biological Psychiatry, 89(2), 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwaningsih, E., & Nurmala, I. (2021). The impact of online game addiction on adolescent mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences, 9(F), 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohilla, S. (2018). Gender difference in gaming addiction among adolescents. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research, 6(1), 461–462. Available online: https://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIR1801088.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Russo-Netzer, P., & Tarrasch, R. (2024). The path to life satisfaction in adolescence: Life orientations, prioritizing, and meaning in life. Current Psychology, 43(18), 16591–16603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvan, S., Bekar, P., Erkul, M., & Efe, E. (2025). The relationship between digital game addiction and levels of anxiety and depression in adolescents receiving cancer treatment. Cancer Nursing, 48(1), 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satapathy, P., Khatib, M. N., Balaraman, A. K., Kaur, M., Srivastava, M., Barwal, A., Prasad, G. V. S., Rajput, P., Syed, R., Sharma, G., Kumar, S., Singh, M. P., Bushi, G., Chilakam, N., Pandey, S., Brar, M., Mehta, R., Sah, S., Gaidhane, A., … Samal, S. K. (2024). Burden of gaming disorder among adolescents: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Public Health in Practice, 9, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J. B., Chan, G., Leung, J., Stjepanović, D., & Connor, J. P. (2024). The nature and characteristics of problem gaming, with a focus on ICD-11 diagnoses. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 37(4), 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schettler, L., Thomasius, R., & Paschke, K. (2022). Neural correlates of problematic gaming in adolescents: A systematic review of structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Addiction Biology, 27(1), e13093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schettler, L. M., Thomasius, R., & Paschke, K. (2024). Emotional dysregulation predicts problematic gaming in children and youths: A cross-sectional and longitudinal approach. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(2), 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S., Zadtootaghaj, S., Sabet, S. S., & Möller, S. (2021, June 14–17). Modeling and understanding the quality of experience of online mobile gaming services. 2021 13th International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX) (pp. 157–162), Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, S. (2023). Life satisfaction and motherhood: The influence of emotion regulation and psychological flexibility. SACAD: John Heinrichs Scholarly and Creative Activity Days, 2023(2023), 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrucca, L., Saqr, M., López-Pernas, S., & Murphy, K. (2023). An introduction and tutorial to model-based clustering in education via Gaussian mixture modelling. arXiv, arXiv:2306.06219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaborn, K., Iseya, S., Hidaka, S., Kobuki, S., & Chandra, S. (2024, May 11–16). Play across boundaries: Exploring cross-cultural maldaimonic game experiences. 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–15), Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skripkauskaite, S., Fazel, M., & OxWell Study Team. (2022). Time spent gaming, device type, addiction scores, and well-being of adolescent English gamers in the 2021 OxWell survey: Latent profile analysis. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 5(4), e41480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szcześniak, M., Bajkowska, I., Czaprowska, A., & Sileńska, A. (2022). Adolescents’ self-esteem and life satisfaction: Communication with peers as a mediator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Taş, I. (2023). The relationship between social ignore and social media addiction among adolescents: Mediator effect of satisfaction with family life. Youth & Society, 55(4), 708–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taş, I. (2025). The role of social exclusion and gender in the relationship between family life satisfaction and game addiction among adolescents. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taş, İ., Karacaoğlu, D., Akpınar, İ., & Taş, Y. (2022). Examining the relationship between family life satisfaction and digital game addiction in adolescents. Online Journal of Technology Addiction and Cyberbullying, 9(1), 28–42. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/ojtac/issue/71122/1081361 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Tomaszek, K., Muchacka-Cymerman, A., & Bosacki, S. (2020). Profiles of problematic internet use and psychosocial functioning in adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C. C., Kim, J. Y., Chen, Q., Rowell, B., Yang, X. J., Kontar, R., Whitaker, M., & Lester, C. (2025). Effect of artificial intelligence helpfulness and uncertainty on cognitive interactions with pharmacists: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 27, e59946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tülübaş, T., Karakose, T., & Papadakis, S. (2023). A holistic investigation of the relationship between digital addiction and academic achievement among students. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(10), 2006–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçur, Ö., & Dönmez, Y. E. (2021). Problematic internet gaming in adolescents, and its relationship with emotional regulation and perceived social support. Psychiatry Research, 296, 113678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usán Supervía, P., & Quílez Robres, A. (2021). Emotional regulation and academic performance in the academic context: The mediating role of self-efficacy in secondary education students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Neut, D., Peeters, M., Boniel-Nissim, M., Klanšček, H. J., Oja, L., & Van Den Eijnden, R. (2023). A cross-national comparison of problematic gaming behavior and well-being in adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 12(2), 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. L., Song, K. R., Zhou, N., Potenza, M. N., Zhang, J. T., & Dong, G. H. (2022). Gender-related differences in involvement of addiction brain networks in internet gaming disorder: Relationships with craving and emotional regulation. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 118, 110574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, B., Muthen, B., Alwin, D. F., & Summers, G. F. (1977). Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociological Methodology, 8, 84–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, H. C., & Watson, P. M. (2023). Critical consumers: How do young women with high autonomous motivation for exercise navigate fitness social media? Computers in Human Behavior, 148, 107893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N., Hou, Y., Jiang, Y., Zeng, Q., & You, J. (2024). Longitudinal relations between social relationships and adolescent life satisfaction: The mediating roles of self-compassion and psychological resilience. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 33(7), 2195–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Q., Liu, F., Chan, K. Q., Wang, N. X., Zhao, S., Sun, X., Shen, W., & Wang, Z. J. (2022). Childhood psychological maltreatment and internet gaming addiction in Chinese adolescents: Mediation roles of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and psychosocial problems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 129, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y., & Tang, L. (2024). The symptom network of internet gaming addiction, depression, and anxiety among children and adolescents. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 29732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y., Yang, Q., & Lei, F. (2023). The relationship of internet gaming addiction and suicidal ideation among adolescents: The mediating role of negative emotion and the moderating role of hope. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, M., & Pandey, N. (2025). Relationship between online gaming, aggression and impulsiveness among young adults: A review. IAHRW International Journal of Social Sciences Review, 13(1), 242–245. [Google Scholar]

- Yaman, F., Çubukcu, A., Küçükali, M., & Yurdakul, I. K. (2020). Social media usage and digital game play of middle and high school students. Sakarya University Journal of Education Faculty, 20(2), 160–174. [Google Scholar]

- Yazici, Z. N., & Kumcağız, H. (2021). The relationship between problematic online game usage, depression, and life satisfaction among university students. Educational Process: International Journal, 10(1), 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M. A., & Uslu, O. (2023). The Mediation of emotion regulation strategies in the relationship between internet addiction and life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educational Process: International Journal, 12(4), 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Zhang, L., Su, X., Zhang, X., & Deng, X. (2025). Association between internet addiction and insomnia among college freshmen: The chain mediation effect of emotion regulation and anxiety and the moderating role of gender. BMC Psychiatry, 25(1), 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, S. M., Hutagalung, F. D., Abd Hamid, H. S. B., & Taresh, S. M. (2025). The power of emotion regulation: How managing sadness influences depression and anxiety? BMC Psychology, 13(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M., Babar, M. S., Babar, M., Sabir, F., Ashraf, F., Tahir, M. J., Ullah, I., Griffiths, M. D., Lin, C.-Y., & Pakpour, A. H. (2022). Prevalence of gaming addiction and its impact on sleep quality: A cross-sectional study from Pakistan. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 78, 103641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., & Zhen, R. (2022). How do physical and emotional abuse affect depression and problematic behaviors in adolescents? The roles of emotional regulation and anger. Child Abuse & Neglect, 129, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zysberg, L., & Raz, S. (2019). Emotional intelligence and emotion regulation in self-induced emotional states: Physiological evidence. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 1. Life Satisfaction | 1 | |||||

| 2. Problematic Digital Gaming | −0.455 ** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Goal | −0.538 ** | 0.407 ** | 1 | |||

| 4. Impulse | −0.526 ** | 0.454 ** | 0.700 ** | 1 | ||

| 5. Non-acceptance | −0.499 ** | 0.480 ** | 0.698 ** | 0.707 ** | 1 | |

| 6. Strategy | −0.567 ** | 0.387 ** | 0.779 ** | 0.717 ** | 0.723 ** | 1 |

| Mean | 14.83 | 20.42 | 5.85 | 5.52 | 4.98 | 5.44 |

| SD | 5.49 | 8.02 | 2.10 | 2.36 | 2.35 | 2.29 |

| Skewness | −0.17 | 0.64 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.36 |

| Kurtosis | −1.18 | −0.43 | −0.81 | −1.00 | −0.92 | −0.85 |

| İndices | Perfect Fit Limit | Acceptable Fit Limit | Scale Indices | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2/DF | 0–2.5 | ≤5 | 2.62 | Acceptable |

| RMSEA | ≤05 | ≤08 | 0.06 | Acceptable |

| SRMR | ≤05 | ≤08 | 0.05 | Perfect |

| CFI | ≥95 | ≥90 | 0.92 | Acceptable |

| GFI | ≥90 | ≥85 | 0.85 | Acceptable |

| IFI | ≥95 | ≥90 | 0.92 | Acceptable |

| Gender | Effect Type | Path | β and p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Direct Effect | Problematic Digital Gaming → Life Satisfaction | −0.33, <0.001 |

| Indirect Effect | Problematic Digital Gaming → Difficulties in Emotion Regulation → Life Satisfaction | −0.18, <0.001 | |

| Total Effect | Combined | −0.51, <0.001 | |

| Male | Direct Effect | Problematic Digital Gaming → Life Satisfaction | −0.12, >0.001 |

| Indirect Effect | Problematic Digital Gaming → Difficulties in Emotion Regulation → Life Satisfaction | −0.39, <0.001 | |

| Total Effect | Combined | −0.51, <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yayla, İ.E.; Dombak, K.; Diril, S.; Düşünceli, B.; Çelik, E.; Yildirim, M. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation as a Mediator and Gender as a Moderator in the Relationship Between Problematic Digital Gaming and Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081092

Yayla İE, Dombak K, Diril S, Düşünceli B, Çelik E, Yildirim M. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation as a Mediator and Gender as a Moderator in the Relationship Between Problematic Digital Gaming and Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081092

Chicago/Turabian StyleYayla, İbrahim Erdoğan, Kübra Dombak, Sena Diril, Betül Düşünceli, Eyüp Çelik, and Murat Yildirim. 2025. "Difficulties in Emotion Regulation as a Mediator and Gender as a Moderator in the Relationship Between Problematic Digital Gaming and Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081092

APA StyleYayla, İ. E., Dombak, K., Diril, S., Düşünceli, B., Çelik, E., & Yildirim, M. (2025). Difficulties in Emotion Regulation as a Mediator and Gender as a Moderator in the Relationship Between Problematic Digital Gaming and Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081092