The Perception of Labor Control and Employee Overtime Behavior in China: The Mediating Role of Job Autonomy and the Moderating Role of Occupational Value

Abstract

1. Introduction

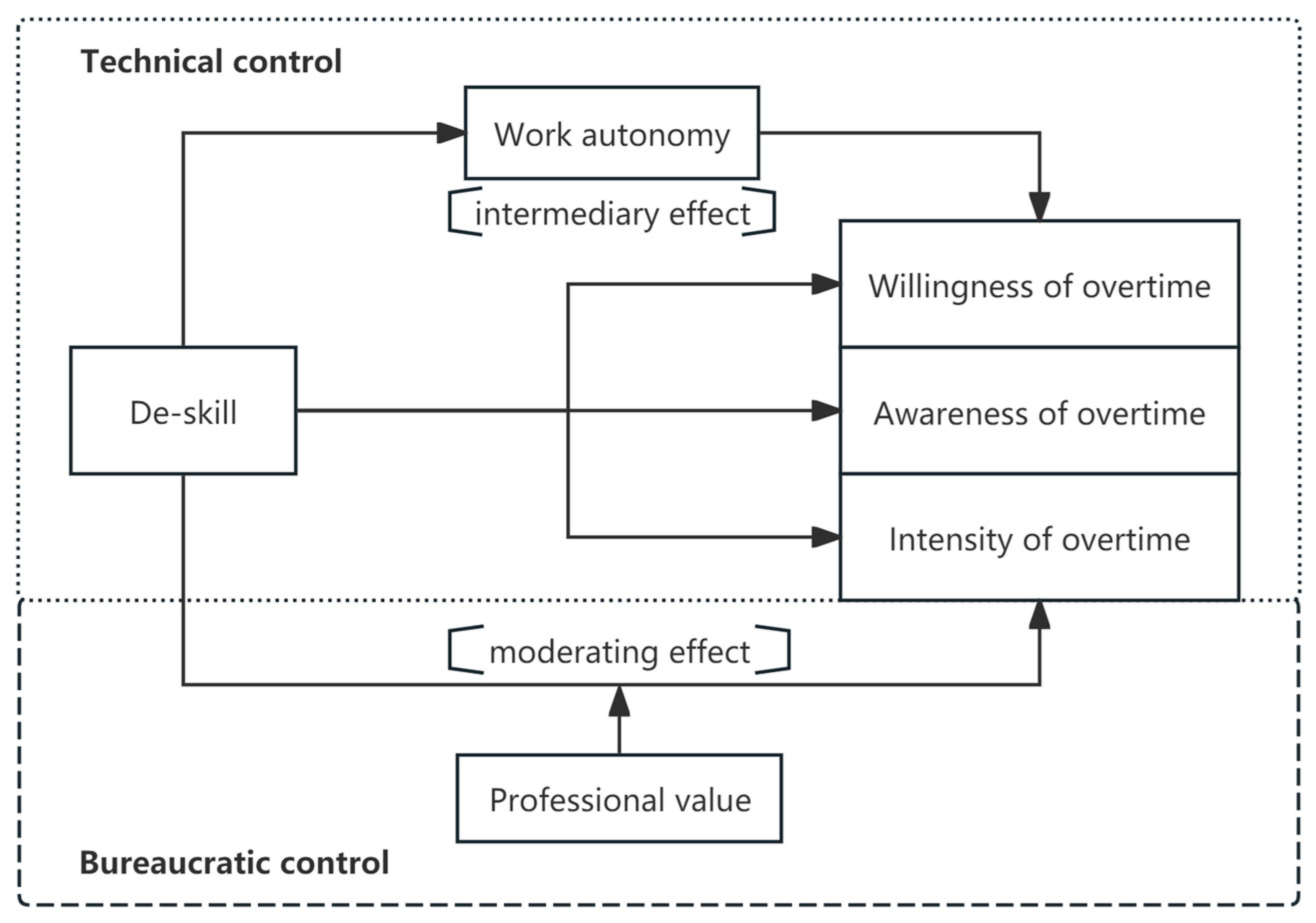

2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1. The Concept and Extension of Overtime Work

2.2. Labor Control and Overtime Behavior

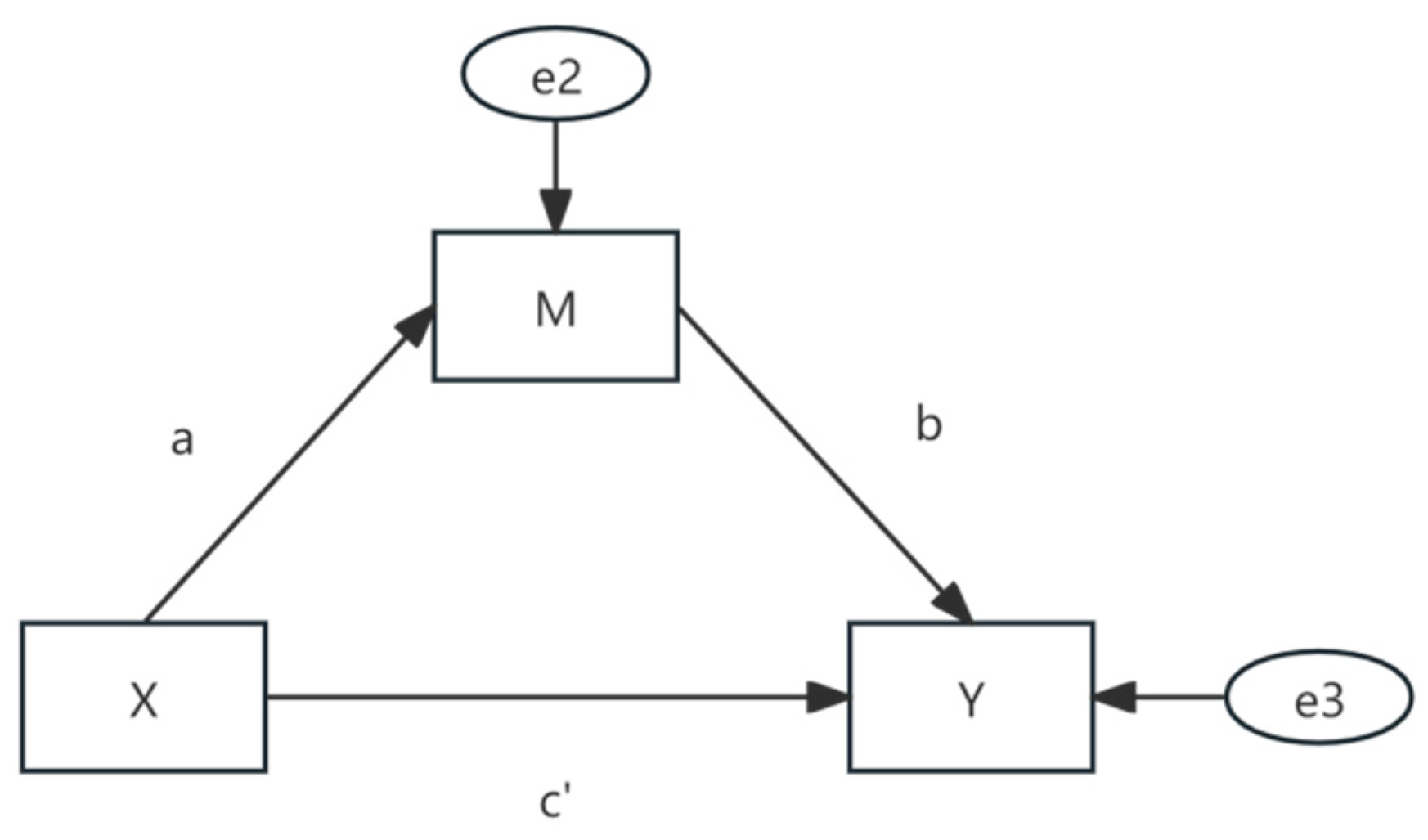

2.3. The Mediating Effect of Job Autonomy

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Career Value Orientation

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Use and Variable Setting

3.1.1. Dependent Variables

3.1.2. Independent Variables

3.1.3. Mediating and Moderating Variables

3.2. Statistical Models

4. Overtime Work Under Labor Control

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Overtime Work Behavior

4.2. Technical Control and Employee Overtime

4.2.1. The Impact of Labor “De-Skilling” on Employees’ Willingness to Work Overtime

4.2.2. The Impact of Labor “De-Skilling” on Employees’ Cognition of Overtime

4.2.3. The Impact of Labor “De-Skilling” on Employees’ Overtime Intensity

4.3. The Mediating Role of Employees’ Job Autonomy

4.3.1. The Role of Labor “De-Skilling” on Employees’ Job Autonomy

4.3.2. The Mediating Effect of Job Autonomy on Employees’ Willingness to Work Overtime

4.3.3. The Mediating Effect of Job Autonomy on Employees’ Cognition of Overtime Work

4.3.4. The Mediating Effect of Job Autonomy on the Overtime Intensity of Employees

4.4. The Moderating Effect of Employees’ Occupational Value Orientation

4.4.1. The Moderating Effect of Occupational Value Orientation on Employees’ Willingness to Work Overtime

4.4.2. The Moderating Effect of Occupational Value Orientation on Employees’ Cognition of Overtime Work

4.4.3. The Regulating Effect of Occupational Value Orientation on the Overtime Intensity of Employees

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. The Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, D. H., Levy, F., & Murnane, R. J. (2003). The skill content of recent technological change: An empirical exploration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1279–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beckers, D. G., Van der Linden, D., Smulders, P. G., Kompier, M. A., Taris, T. W., & Geurts, S. A. (2008). Voluntary or involuntary? Control over overtime and rewards for overtime in relation to fatigue and work satisfaction. Work & Stress, 22(1), 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Braverman, H. (1978). Labor and monopoly capital: The degradation of labor in the twentieth century (S. Fang, L. Wu, & Y. Lin, Trans.; pp. 65–172). Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burawoy, M. (2008). Manufacturing consent: The changes in the labor process of monopoly capitalism (R. Li, Trans.; pp. 1–193). Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H., & Shi, Y. (2016). De-technologization of labor process, politics of spatial production and overtime overtime—An analysis based on data from the 2012 China labor force dynamics survey. Journal of Northwestern Normal University (Social Science Edition), 53(1), 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z., Wang, Y., & Lee, C. (2018). Work orientation and overtime work: The compensatory role of income vs. skill development. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(4), 763–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H., & van der Horst, M. (2020). Flexible working and unpaid overtime in the UK: The role of gender, parental and occupational status. Social Indicators Research, 2, 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1988). Empowerment as a process: Integrating theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeringer, P. B., & Piore, M. J. (1971). Internal labor markets and manpower analysis. D.C. Heath and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R. (1979). Contested terrain: The transformation of the workplace in the twentieth century. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, S. J., Korczynski, M., Shire, K., & Tam, M. (1995). On the front line: Organization of work in the information economy. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48(2), 233–258. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Z., Xiao, M., Wang, H., & Shan, C. (2021). What are the pros and cons? A review and prospects of overtime work research. China Human Resource Development, 38(12), 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Times. (2018). Hunan Hengyang Foxconn exposed: Workers work 80 h of overtime a month with an hourly wage of 14.5 yuan. Available online: https://society.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnK9j2r (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Guo, F. (2022). The impact of wage rate increase on overtime labor of migrant workers. Journal of Population, 44(04), 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Harilal, K. N. (1989). Deskilling and wage differentials in construction industry. Economic& Political Weekly, 24, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett, S. A., & Carolyn, B. L. (2007). Extreme jobs: The dangerous allure of the 70-h workweek. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Higher Education Foxconn Research Group. (2010). General report on foxconn research in colleges and universities. Available online: https://tech.sina.com.cn/it/2010-10-09/09574726168.shtml (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H., & He, X. (2020). “No Overtime, No Life”: The labor system of internet knowledge laborers. Exploration and Controversy, 5, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, W., & Zhong, K. (2018). Another kind of entertainment to death?—Experience, illusion, and labor control in the production process of variety entertainment programs. Sociological Research, 3(06), 159–185+245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A. L. (2018). Precarious lives: Job insecurity and well-being in rich democracies. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katherine, M. R., & Cynthia, A. T. (2012). High tech tethers and work-family conflict: A conservation of resources approach. Engineering Management Research, 1(1), 29. [Google Scholar]

- Kunda, G. S. (1992). Engineering culture: Control and commitment in a high-tech corporation. Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. (2021). The involvement and regulation of unpaid labor in the digital economy. Social Science, 11, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q., & Liu, J. (2020). Beyond the sentiment: A study of the factory polity of “voluntary overtime work” in internet small and medium-sized enterprises. Social Development Research, 7(01), 204–224+246. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., Chen, Y., Qi, H., & Xu, Z. (2012). Survival wage, overtime labor and the sustainable development of china’s economy. Review of Political Economy, 3(03), 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M. (2019). 996 Overtime work system: A study on management control changes in internet companies. Science and Society, 3, 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, C., & Chen, Y. (2014). Research on hidden forced labor in the textile industry in the transition period—Taking a large joint-stock state-owned textile enterprise in southern Jiangsu as a case. Journal of Harbin Institute of Technology (Social Science Edition), 5, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1972). The complete works of Marx and Engels (Compilation and Translation Bureau of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin’s Writings of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China Trans.; Vol. 23, pp. 463–464). People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C. (2003). Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2022). The burnout challenge: Managing people’s relationships with their jobs. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, W., & Feng, X. (2020). A study on overtime work and psychosocial consequences of 996 working youths—An empirical analysis based on CLDS data. China Youth Studies, 5, 76–84,99. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, G. R., & Hackman, J. R. (1980). Work redesign. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, R. N. S., & Barron, P. E. (2007). Developing a framework for understanding the impact of deskilling and standardisation on the turn over rand attrition of chefs. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26(4), 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T. (2011). Analysis of the criteria for determining working hours. Law Science, 5, 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. (1983). A study of the nature and causes of national wealth (D. Guo, & Y. Wang, Trans.; p. 62). Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z., & Huang, J. (2021). Overtime dependency system: Re-examining the problem of excessive overtime work of young migrant workers. China Youth Studies, 8, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Super, D. E. (1957). The psychology of careers. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. (2007). In search of meaning. Shanghai Pictorial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., & Fang, C. (2022). Raising wages or reducing overtime? Institutional differences in contemporary youth job satisfaction. China Youth Studies, 1, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. (2016). The system construction of working time benchmark and legislative improvement. Legal Science (Journal of Northwest University of Politics and Law), 1, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. (1922). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F. (2007). The labor process of capitalism: Transformation from fordism to post-fordism. Journal of Renmin University of China, 2, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y., & Ye, X. (2020). Technological upgrading and labor downgrading?—A sociological examination based on three “machine-for-human” factories. Sociological Research, 3, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X. (2020). Taking the self as an enterprise—Over-marketization and self-management of R&D employees. Sociological Research, 35(6), 136–159. [Google Scholar]

- You, Z. (2016). Management control and workers’ resistance—A review of relevant literature in the study of capitalist labor process. Sociological Research, 4, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X., Huang, Y., & Li, M. (2021). Industry competition, corporate strategy and employee subjectivity: A multi-case study based on the phenomenon of overtime work of employees in Internet enterprises. China Human Resource Development, 38(11), 106–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhilian Recruitment. (2025). Research report on workplace satisfaction index 2024. Available online: https://www.eeo.com.cn/2025/0120/707528.shtml (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Zhu, Z. (2018). Self-employment choice and market returns of migrant workers—An empirical test based on the 2014 national mobile population dynamics monitoring survey data. Population and Economy, 5, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, J. (2018). From managed hands to managed minds—A study of overtime under the perspective of labor process. Sociological Research, 33(3), 74–91. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Name | Variable Type | Mean/Percent | Standard Deviation | Indicates | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overtime hours | Continuous variable | 8.20 | 12.19 | Weekly overtime (h) Value range: [0, 120] | 5263 |

| Objective overtime | Binary categorical variable | No = 47.7%; Yes = 52.3% | 0.500 | 0 = no; 1 = yes | 5263 |

| Subjective overtime | Binary categorical variable | No = 67.4%; Yes = 32.6% | 0.469 | 0 = no; 1 = yes | 5263 |

| Voluntary overtime | Binary categorical variable | No = 35.7%; Yes = 64.3% | 0.479 | 0 = no; 1 = yes | 1719 |

| Unconscious overtime | Binary categorical variable | No = 37.9%; Yes = 62.1% | 0.485 | 0 = no; 1 = yes | 2750 |

| Age | Continuous variable | 40.25 | 10.938 | Value range: [18, 64] | 5263 |

| Sex | Binary categorical variable | Female = 44.6%; Male = 55.4% | 0.497 | 0 = female; 1 = male | 5263 |

| Educational level | Binary categorical variable | College degree or below = 68.8%; College and above = 31.2% | 0.464 | 0 = junior college or below; 1 = college degree or above | 5263 |

| Household registration | Binary categorical variable | Rural = 58.9%; Town = 47.1% | 0.499 | 0 = rural; 1 = town | 5263 |

| Trade unionist | Binary categorical variable | No = 66.9%; Yes = 33.1% | 0.470 | 0 = no; 1 = yes | 5263 |

| Labor contract | Binary categorical variable | No = 46.8%; Yes = 53.2% | 0.499 | 0 = no; 1 = yes | 5263 |

| Provide accommodation | Binary categorical variable | No = 83.3%; Yes = 16.7% | 0.373 | 0 = no; 1 = yes | 5263 |

| Job autonomy | Continuous variable | 5.15 | 1.988 | Value range: [3, 9] | 5263 |

| Annual income (logarithm) | Continuous variable | 9.59 | 2.781 | Value range: [0, 15] | 5263 |

| Development orientation | Continuous variable | 61.24 | 17.029 | Value range: [0, 100] | 5263 |

| Survival orientation | Continuous variable | 72.97 | 14.253 | Value range: [0, 100] | 5263 |

| Objective Overtime | Subjective Overtime | Voluntary Overtime | Unconscious Overtime | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 52.25 | 32.64 | 64.34 | 62.15 |

| No | 47.75 | 67.36 | 35.66 | 37.85 |

| Total | 100 (5263) | 100 (5263) | 100 (1719) | 100 (2750) |

| Variable | Reference Model | Labor Control Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| De-skilling of labor | −0.407 *** | ||

| (0.114) | |||

| Personal characteristics | Age | −0.006 | −0.005 |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | ||

| Gender (male = 1) | −0.037 | −0.075 | |

| (0.105) | (0.106) | ||

| Household registration (town = 1) | −0.275 * | −0.303 * | |

| (0.123) | (0.125) | ||

| Education level (college or above = 1) | 0.147 | 0.094 | |

| (0.131) | (0.133) | ||

| Income | 0.061 ** | 0.059 ** | |

| (0.019) | (0.020) | ||

| Enterprise characteristics | Union (have = 1) | −0.245 * | −0.298 * |

| (0.117) | (0.118) | ||

| Labor contract (have = 1) | 0.0314 | −0.0412 | |

| (0.114) | (0.116) | ||

| Accommodation available (Yes = 1) | 0.419 ** | 0.432 ** | |

| (0.136) | (0.136) | ||

| Constant | 0.323 | 0.562 + | |

| (0.288) | (0.301) | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0230 | 0.0174 | |

| Observations | 1719 | 1719 | |

| Variable | Reference Model | Labor Control Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| De-skilling of labor | 0.362 *** | ||

| (0.087) | |||

| Personal characteristics | Age | 0.0160 *** | 0.0142 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | ||

| Gender (male = 1) | −0.138 + | −0.106 | |

| (0.084) | (0.084) | ||

| Household registration (town = 1) | −0.0356 | −0.0193 | |

| (0.097) | (0.097) | ||

| Education level (college or above = 1) | −0.394 *** | −0.345 ** | |

| (0.119) | (0.119) | ||

| Income | −0.0256 + | −0.0222 | |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | ||

| Enterprise characteristics | Union (have = 1) | −0.354 *** | −0.297 ** |

| (0.102) | (0.103) | ||

| Labor contract (have = 1) | −0.494 *** | −0.430 *** | |

| (0.088) | (0.090) | ||

| Accommodation available (yes = 1) | −0.347 *** | −0.350 *** | |

| (0.099) | (0.100) | ||

| Constant | 0.680 ** | 0.463 * | |

| (0.217) | (0.223) | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.046 | 0.051 | |

| Observations | 2750 | 2750 | |

| Variable | Reference Model | Labor Control Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| De-skilling of labor | 1.343 ** | ||

| (0.492) | |||

| Personal characteristics | Age | −0.120 *** | −0.127 *** |

| (0.025) | (0.025) | ||

| Gender (male = 1) | 1.690 *** | 1.803 *** | |

| (0.469) | (0.469) | ||

| Household registration (town = 1) | −4.749 *** | −4.68 *** | |

| (0.553) | (0.554) | ||

| Education level (college or above = 1) | −5.308 *** | −5.129 *** | |

| (0.542) | (0.547) | ||

| Income | 0.052 | 0.064 | |

| (0.102) | (0.102) | ||

| Enterprise characteristics | Union (have = 1) | −1.546 ** | −1.340 ** |

| (0.503) | (0.509) | ||

| Labor contract (have = 1) | −1.060 * | −0.840 + | |

| (0.492) | (0.493) | ||

| Accommodation available (yes = 1) | 3.495 *** | 3.503 *** | |

| (0.717) | (0.716) | ||

| Constant | 11.45 *** | 10.64 *** | |

| (1.392) | (1.429) | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.086 | 0.087 | |

| Observations | 5263 | 5263 | |

| Variable | Job Autonomy Model |

|---|---|

| De-skilling of labor | 0.120 * |

| (0.059) | |

| Individual and firm characteristic variables | Controlled |

| Constant | 5.525 *** |

| (0.157) | |

| Observations | 5263 |

| R-squared | 0.022 |

| Type | Coefficient | Self-Service Standard Error | Z-Value | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | −0.008 | 0.004 | −1.96 | 0.050 | −0.016 | −0.001 |

| Direct effect | −0.083 | 0.025 | −3.19 | 0.001 | −0.137 | −0.034 |

| Total effect | −0.091 | 0.026 | −3.55 | 0.000 | −0.141 | −0.041 |

| Proportion of mediating effect | 8.5% | |||||

| Type | Coefficient | Self-Service Standard Error | Z-Value | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | −0.001 | 0.001 | −1.33 | 0.183 | −0.004 | 0.000 |

| Direct effect | 0.082 | 0.199 | 4.23 | 0.000 | 0.045 | 0.125 |

| Total effect | 0.081 | 0.195 | 4.16 | 0.000 | 0.044 | 0.120 |

| Proportion of mediating effect | −1.7% | |||||

| Type | Coefficient | Self-Service Standard Error | Z-Value | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | 0.076 | 0.042 | 1.80 | 0.048 | 0.007 | 0.159 |

| Direct effect | 1.267 | 0.498 | 2.54 | 0.011 | 0.287 | 2.245 |

| Total effect | 1.343 | 0.499 | 2.69 | 0.007 | 0.364 | 2.321 |

| Proportion of mediating effect | 5.7% | |||||

| Variable | Voluntary Overtime | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control Variable | Controlled | ||

| Independent variable | De-skilling of labor | −0.365 ** | −0.346 ** |

| (0.115) | (0.116) | ||

| Occupational value orientation | Development orientation | 0.016 *** | 0.012 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.003) | ||

| Survival orientation | −0.0001 | −0.004 | |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | ||

| Interaction term | Labor de-skilling × development orientation factor | −0.010 + | |

| (0.006) | |||

| Labor de-skilling × survival-oriented factor | 0.009 | ||

| (0.007) | |||

| Constant | −0.418 | 0.098 | |

| (0.465) | (0.477) | ||

| Observations | 1719 | 1719 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0312 | 0.0317 | |

| Variable | Voluntary Overtime | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control Variable | Controlled | ||

| Independent variable | De-skilling of labor | 0.397 *** | 0.381 *** |

| (0.088) | (0.088) | ||

| Occupational value orientation | Development orientation | −0.001 | 0.004 |

| (0.003) | (0.002) | ||

| Survival orientation | −0.006 * | −0.008 + | |

| (0.003) | (0.004) | ||

| Interaction term | Labor de-skilling × development orientation factor | 0.010 * | |

| (0.005) | |||

| Labor de-skilling × survival-oriented factor | 0.004 | ||

| (0.006) | |||

| Constant | 0.975 ** | 0.805 * | |

| (0.367) | (0.391) | ||

| Observations | 2750 | 2750 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.054 | 0.053 | |

| Variable | Voluntary Overtime | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control Variable | Controlled | ||

| Independent variable | De-skilling of labor | 1.123 * | 1.130 * |

| (0.496) | (0.497) | ||

| Occupational value orientation | Development orientation | −0.068 ** | −0.034 * |

| (0.021) | (0.015) | ||

| Survival orientation | 0.087 *** | 0.073 *** | |

| (0.016) | (0.020) | ||

| Interaction term | Labor de-skilling × development orientation factor | 0.067 * | |

| (0.031) | |||

| Labor de-skilling × survival-oriented factor | 0.027 | ||

| (0.033) | |||

| Constant | 8.953 *** | 7.700 *** | |

| (2.130) | (2.078) | ||

| Observations | 5263 | 5263 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.094 | 0.093 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, T. The Perception of Labor Control and Employee Overtime Behavior in China: The Mediating Role of Job Autonomy and the Moderating Role of Occupational Value. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050691

Dong W, Wang Y, Zhao T. The Perception of Labor Control and Employee Overtime Behavior in China: The Mediating Role of Job Autonomy and the Moderating Role of Occupational Value. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):691. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050691

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Wei, Yijie Wang, and Tingting Zhao. 2025. "The Perception of Labor Control and Employee Overtime Behavior in China: The Mediating Role of Job Autonomy and the Moderating Role of Occupational Value" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050691

APA StyleDong, W., Wang, Y., & Zhao, T. (2025). The Perception of Labor Control and Employee Overtime Behavior in China: The Mediating Role of Job Autonomy and the Moderating Role of Occupational Value. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050691