On the Prospective Application of Behavioral Momentum Theory and Resurgence as Choice in the Treatment of Problem Behavior: A Brief Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

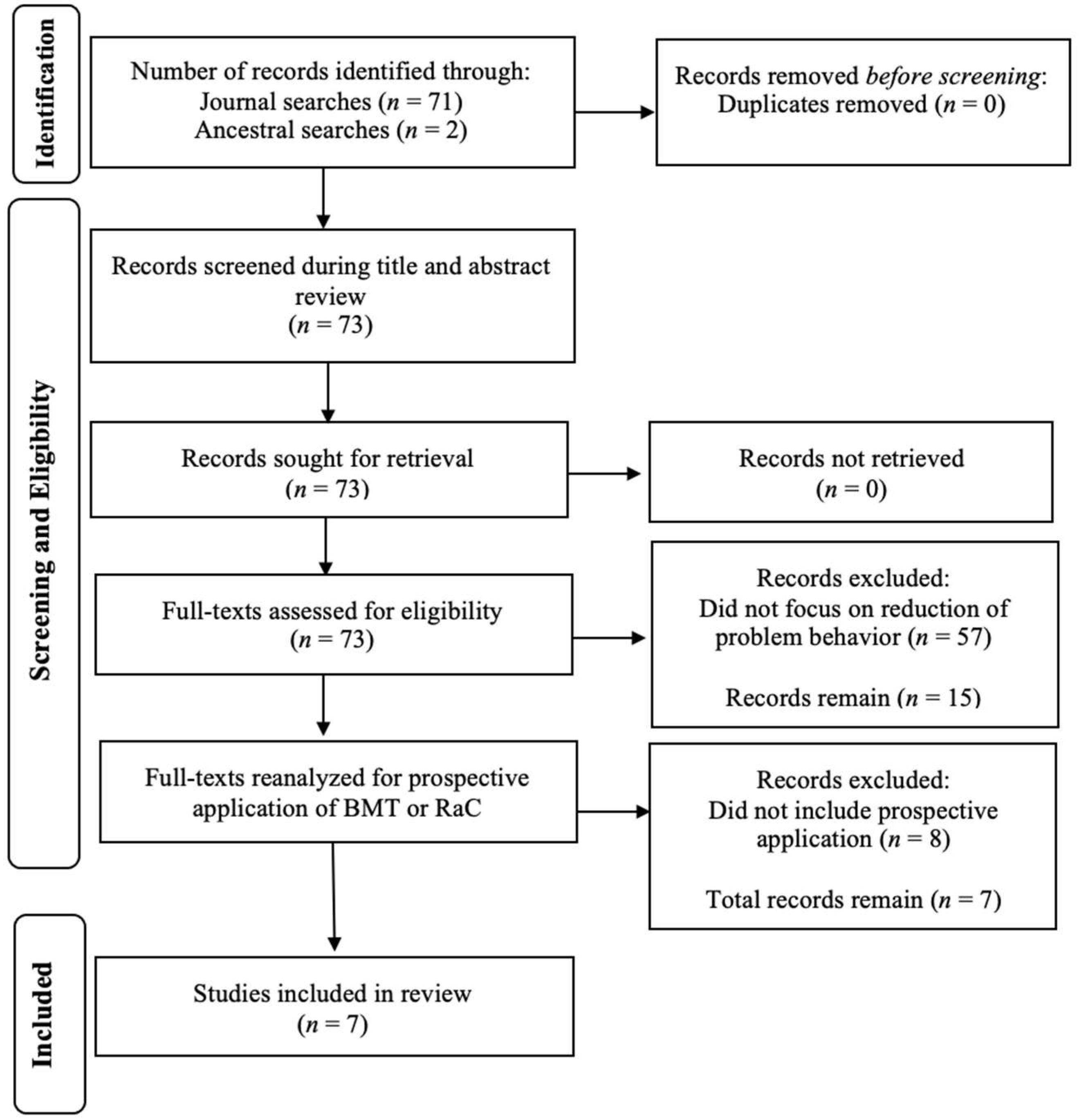

2. Methods: Prevalence of Prospective Applications of BMT and RaC

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Potential Barrier: Lack of Familiarity with Quantitative Models

3.1.1. Potential Solution: Develop and Disseminate Model-Specific Training and Tutorials

3.1.2. Potential Solution: Expanding Training in Quantitative Models Through Coursework and Certification Standards

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RaC | Resurgence as Choice |

| BMT | Behavioral Momentum Theory |

| JABA | Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis |

| JEAB | Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior |

| 1 | This also includes if BMT or RaC was mentioned in part. For example, if an article had the keyword “behavioral momentum”, those were included in the first step. For the purpose of this review, we did not make a distinction between RaC (Shahan & Craig, 2017), and Resurgence as Choice in Context (RaC2; Shahan et al., 2020). |

| 2 | The articles included through the ancestral search (a) included, “…A prospective analysis”, in its title (i.e., Greer et al., 2024) or (b) otherwise met every other criteria for inclusion sans mentioning a model in the keyword, title, or abstract. Therefore, we reviewed those articles. Although BMT or RaC was not mentioned in the title, keywords, or abstract, those two articles met every other inclusion criteria. Given the scant nature of this research, it seemed wise to include them. |

| 3 | Consider BMT, RaC, and Resurgence as Choice in Context (RaC2). BMT has substantial empirical evidence; it has led to further understanding of behavioral persistence and relapse and is one of the models that has been successfully applied in a prospective manner. However, researchers have recently identified several shortcomings of BMT (e.g., failure to fully account for disruptive effects of alternative reinforcement; see (Shahan & Craig, 2017) and (Shahan & Sweeney, 2011) for discussions). Thus, RaC was developed to account for the shortcomings of BMT. Shortly thereafter, RaC2 emerged to better account for the local effects of rapid alternation between different schedules of alternative reinforcement and other procedural arrangements. |

References

- Association for Behavior Analysis International [ABAI]. (n.d.). Verified course sequence program. Available online: https://www.abainternational.org/vcs/bacb.aspx (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Baum, W. M., & Rachlin, H. C. (1969). Choice as time allocation. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 12(6), 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB]. (2022). BCBA test content outline (6th ed.). BACB. Available online: https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/bcba-outline-6thEd/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Briggs, A. M., & Greer, B. D. (2021). Intensive behavioral intervention units. In A. Maragakis, C. Drossel, & T. J. Waltz (Eds.), Applications of behavior analysis to healthcare and beyond. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, A. R. (2023). Resistance to change, of behavior and of theory. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 120(3), 440–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A. R., Sullivan, W. E., & Roane, H. S. (2019). Further evaluation of a nonsequential approach to studying operant renewal. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 112(2), 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critchfield, T. S., & Reed, D. D. (2009). What are we doing when we translate from quantitative models. The Behavior Analyst, 32(2), 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, E. S. L., Kranak, M. P., Fielding, C., Curiel, H., & Miller, M. M. (2023). Behavior analysis in college classrooms: A scoping review. Behavioral Interventions, 38(1), 219–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowdy, A., & Jacobs, K. W. (2019). An empirical evaluation of the disequilibrium model to increase independent seatwork for an individual diagnosed with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(3), 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falligant, J. M., Kranak, M. P., McNulty, M. K., Schmidt, J. D., Hausman, N. L., & Rooker, G. W. (2021). Prevalence of renewal of problem behavior: Replication and extension to an inpatient setting. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 54(1), 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, W. W. (Principal Investigator). (2015–2020). Preventing relapse of destructive behavior using behavioral momentum theory. Project No. 7R01HD083214-06 [Grant]. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. Available online: https://reporter.nih.gov/search/qTZJS6aINU6vbnZ9fuYEFw/project-details/10129514#details (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Fisher, W. W., Greer, B. D., Fuhrman, A., Saini, V., & Simmons, C. (2018). Minimizing resurgence of destructive behavior using behavioral momentum theory. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 51(4), 831–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, W. W., Greer, B. D., Mitteer, D. R., & Fuhrman, A. M. (2022). Translating quantitative theories of behavior into improved clinical treatments for problem behavior. Behavioural Processes, 198, 104639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, W. W., Greer, B. D., Shahan, T. A., & Norris, H. M. (2023). Basic and applied research on extinction bursts. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 56(1), 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, W. W., Saini, V., Greer, B., Sullivan, W., Roane, H., Fuhrman, A., Craig, A., & Kimball, R. (2019). Baseline reinforcement rate and resurgence of destructive behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 111(1), 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, B. D. (2021, May 27–31). SQAB tutorial: Using quantitative theories of relapse to improve functional communication. Association for Behavior Analysis International 47th Annual Convention, Online. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, B. D., Fisher, W. W., Retzlaff, B. J., & Fuhrman, A. M. (2020). A preliminary evaluation of treatment duration on the resurgence of destructive behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 113(1), 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, B. D., Fisher, W. W., Romani, P. W., & Saini, V. (2016a). Behavioral momentum theory: A tutorial on response persistence. The Behavior Analyst, 39(2), 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, B. D., Fisher, W. W., Saini, V., Owen, T. M., & Jones, J. K. (2016b). Functional communication training during reinforcement schedule thinning: An analysis of 25 applications. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 49(1), 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, B. D., & Shahan, T. A. (2019). Resurgence as choice: Implications for promoting durable behavior change. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52(3), 816–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, B. D., Shahan, T. A., Fisher, W. W., Mitteer, D. R., & Fuhrman, A. M. (2023). Further evaluation of treatment duration on the resurgence of destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 56(1), 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, B. D., Shahan, T. A., Irwin Helvey, C., Fisher, W. W., Mitteer, D. R., & Fuhrman, A. M. (2024). Resurgence of destructive behavior following decreases in alternative reinforcement: A prospective analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 57(3), 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustyi, K. M., Ryan, A. H., & Hall, S. S. (2023). A scoping review of behavioral interventions for promoting social gaze in individuals with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 100, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin Helvey, C., Fisher, W. W., Greer, B. D., Fuhrman, A. M., & Mitteer, D. R. (2023). Resurgence of destructive behavior following differential rates of alternative reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 56(4), 804–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J., Kranak, M. P., Mitteer, D. R., Melanson, I., & Fahmie, T. A. (2025). A scoping review of consecutive controlled case series studies. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 58(2), 270–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killeen, P. R., & Sitomer, M. T. (2003). MPR. Behavioural Processes, 62(1–3), 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranak, M. P., & Falligant, J. M. (2021). Further investigation of resurgence following schedule thinning: Extension to an inpatient setting. Behavioral Interventions, 36(4), 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureano, B., & Falligant, J. M. (2023). Modelling behavioral persistence with resurgence as choice in context (RaC2): A tutorial. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 16(2), 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, F. C., & Critchfield, T. S. (2010). Translational research in behavior analysis: Historical traditions and imperative for the future. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 93(3), 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitteer, D. R., Greer, B. D., Randall, K. R., & Haney, S. D. (2022). On the scope and characteristics of treatment relapse when treating destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 55(3), 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muething, C., Call, N., Pavlov, A., Ringdahl, J., Gillespie, S., Clark, S., & Mevers, J. L. (2020). Prevalence of renewal of problem behavior during context changes. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(3), 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review?: Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic and a scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, J. A. (2002). Measuring behavior momentum. Behavioural Processes, 57(2–3), 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, J. A. (2008). Control, prediction, order, and the joys of research. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 89(1), 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, J. A., Craig, A. C., Cunningham, P. J., Podlesnik, C. A., Shahan, T. A., & Sweeney, M. M. (2017). Quantitative models of persistence and relapse from the perspective of behavioral momentum theory: Fits and misfits. Behavioural Processes, 141(1), 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevin, J. A., & Grace, R. C. (2000). Behavioral momentum and the law of effect. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23(1), 73–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevin, J. A., & Shahan, T. A. (2011). Behavioral momentum theory: Equations and applications. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 44(4), 877–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, D., Hoerger, M., & Mace, F. C. (2014). Treatment relapse and behavior momentum theory. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(4), 814–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, D. D., Niileksela, C. R., & Kaplan, B. A. (2013). Behavioral economics: A tutorial for behavior analysts in practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 6(1), 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, V., Fisher, W. W., & Pisman, M. D. (2017). Persistence during and resurgence following noncontingent reinforcement implemented with and without extinction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 50(2), 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieltz, K. M., Wacker, D. P., Ringdahl, J. E., & Berg, W. K. (2017). Basing assessment and treatment of problem behavior on behavioral momentum theory: Analyses of behavioral persistence. Behavioural Processes, 141(1), 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahan, T. A. (2022). A theory of the extinction burst. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 45(3), 495–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahan, T. A., Browning, K. O., & Nall, R. W. (2020). Resurgence as choice in context: Treatment duration and on/off alternative reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 113(1), 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahan, T. A., & Craig, A. R. (2017). Resurgence as choice. Behavioural Processes, 141(1), 100–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahan, T. A., & Greer, B. D. (2021). Destructive behavior increases as a function of reductions in alternative reinforcement during schedule thinning: A retrospective qualitative analysis. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 116(2), 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahan, T. A., Sutton, G. M., Allsburg, J. V., Avellaneda, M., & Greer, B. D. (2024). Resurgence following higher or lower quality alternative reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 121(2), 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahan, T. A., & Sweeney, M. M. (2011). A model of resurgence based on behavioral momentum theory. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 95(1), 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S. W., & Greer, B. D. (2023). Behavioral momentum theory. In J. L. Matson (Ed.), Handbook of applied behavior analysis: Integrating research into practice (pp. 123–139). Springer Nature Switzerland AG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 429–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trump, C. E., Herrod, J. L., Ayers, K. M., Ringdahl, J. E., & Best, L. (2021). Behavior momentum theory and humans: A review of the literature. The Psychological Record, 71(1), 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgeon, S., & Lanovaz, M. J. (2020). Tutorial: Applying machine learning in behavioral research. Perspectives on Behavior Science, 43(4), 697–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacker, D. P., Harding, J. W., Berg, W. K., Lee, J. F., Schieltz, K. M., Padilla, Y. C., Nevin, J. A., & Shahan, T. A. (2011). An evaluation of persistence of treatment effects during long-term treatment of destructive behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 96(2), 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kranak, M.P.; Falligant, J.M.; Jones, C.; Stephens, M.; Wessel, M. On the Prospective Application of Behavioral Momentum Theory and Resurgence as Choice in the Treatment of Problem Behavior: A Brief Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050688

Kranak MP, Falligant JM, Jones C, Stephens M, Wessel M. On the Prospective Application of Behavioral Momentum Theory and Resurgence as Choice in the Treatment of Problem Behavior: A Brief Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):688. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050688

Chicago/Turabian StyleKranak, Michael P., John Michael Falligant, Chloe Jones, Meredith Stephens, and Megan Wessel. 2025. "On the Prospective Application of Behavioral Momentum Theory and Resurgence as Choice in the Treatment of Problem Behavior: A Brief Review" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050688

APA StyleKranak, M. P., Falligant, J. M., Jones, C., Stephens, M., & Wessel, M. (2025). On the Prospective Application of Behavioral Momentum Theory and Resurgence as Choice in the Treatment of Problem Behavior: A Brief Review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050688