Quality of Life in Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review of the Impact of Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychological Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Process, Eligibility Criteria and Data Extraction

2.3. Methodological Quality Appraisal

3. Results

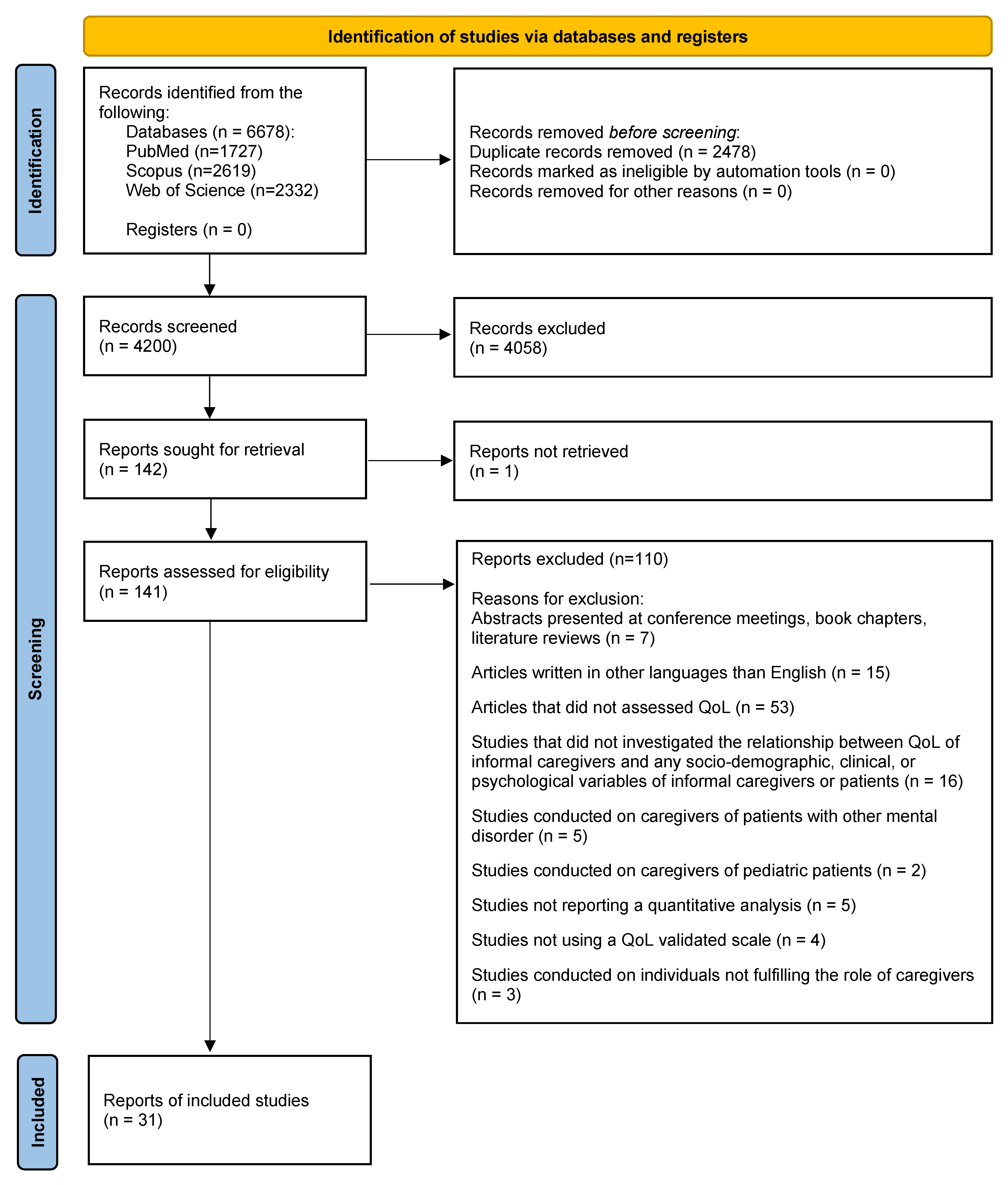

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.3. Critical Assessment and Methodological Quality of the Included Articles

3.4. Sociodemographic Factors

3.4.1. Gender

3.4.2. Age

3.4.3. Educational Level

3.4.4. Employment Status

3.4.5. Kinship

3.4.6. Living Situation

3.4.7. Marital Status

3.4.8. Family Income

3.4.9. Physical Health

3.4.10. Time Spent Caregiving

3.4.11. Ethnicity

3.4.12. Patients’ Sociodemographic Factors

3.5. Patient’s Clinical Factors

3.5.1. Duration of Illness

3.5.2. Symptom Severity

3.5.3. Number of Hospitalizations and Comorbidities

3.6. Caregiver’s Psychological Factors

3.6.1. Burden of Care

3.6.2. Coping Strategies

3.6.3. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

3.6.4. Social and Family Support

3.6.5. Hope and Religious Involvement

3.6.6. Affiliate Stigma and Expressed Emotion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PwS | patient(s) with schizophrenia |

| QoL | quality of life |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PICO | Patient/Population, Intervention/Exposure, Comparison and Outcome |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| WHOQoL-Bref | World Health Organization Quality of Life scale—abbreviated version |

| Schizophrenia Caregiver Quality of Life Questionnaire | S-CGQoL |

| SF-36 | Short Form-36 Health Survey |

| SF-12 v1 | Short Form-12 Health Survey, version 1 |

| SD | standard deviation |

| PANSS | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation |

References

- Addington, J., & Heinssen, R. (2012). Prediction and prevention of psychosis in youth at clinical high risk. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(1), 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adewuya, A. O., Owoeye, O. A., & Erinfolami, A. R. (2011). Psychopathology and subjective burden amongst primary caregivers of people with mental illness in South-Western Nigeria. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 46(12), 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcañiz, M., & Solé-Auró, A. (2018). Feeling good in old age: Factors explaining health-related quality of life. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango, C., Buitelaar, J. K., Correll, C. U., Díaz-Caneja, C. M., Figueira, M. L., Fleischhacker, W. W., Marcotulli, D., Parellada, M., & Vitiello, B. (2022). The transition from adolescence to adulthood in patients with schizophrenia: Challenges, opportunities and recommendations. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 59, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A. G., & Voruganti, L. N. P. (2008). The burden of schizophrenia on caregivers. PharmacoEconomics, 26(2), 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadalla, A. W., Ohaeri, J. U., Salih, A. A., & Tawfiq, A. M. (2005). Subjective quality of life of family caregivers of community living Sudanese psychiatric patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(9), 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbeito, S., Sánchez-Gutiérrez, T., Becerra-García, J. A., González Pinto, A., Caletti, E., & Calvo, A. (2020). A systematic review of online interventions for families of patients with severe mental disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, L., Caqueo-Urízar, A., Richieri, R., Lancon, C., Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J., & Auquier, P. (2012). Quality of life among caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: A cross-cultural comparison of Chilean and French families. BMC Family Practice, 13(1), 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G. M., Couchman, G. M., Perlesz, A., Nguyen, A. T., Singh, B., & Riess, C. (2006). Multiple-family group treatment for English- and Vietnamese-speaking families living with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services, 57(4), 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P. F., Miller, B. J., Lehrer, D. S., & Castle, D. J. (2009). Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 35(2), 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caqueo-Urízar, A., Alessandrini, M., Zendjidjian, X., Urzúa, A., Boyer, L., & Williams, D. R. (2016a). Religion involvement and quality of life in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia in Latin-America. Psychiatry Research, 246, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caqueo-Urízar, A., Urzúa, A., & Boyer, L. (2016b). Caregivers’ perception of patients’ cognitive deficit in schizophrenia and its influence on their quality of life. Psicothema, 2(28), 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, W., Chan, S. W., & Morrissey, J. (2007). The perceived burden among Chinese family caregivers of people with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(6), 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J. Y. A., Yeo, Y. T. T., & Goh, Y. S. (2024). Effects of psychoeducation on caregivers of individuals experiencing schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 33(6), 1962–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, M., West, S., Hunt, G. E., McLean, L., & Kornhaber, R. (2020). A Qualitative systematic review of caregivers’ experiences of caring for family diagnosed with schizophrenia. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(8), 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M., Lima, A. F. B. d. S., Silva, C. P. d. A., Miguel, S. R. P. d. S., & Fleck, M. P. d. A. (2022). Quality of life of family primary caregivers of individuals with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia in south of Brazil. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(4), 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Font, J., & Vilaplana-Prieto, C. (2022). Mental health effects of caregivers respite: Subsidies or supports? The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 23, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csoboth, C., Witt, E. A., Villa, K. F., & O’Gorman, C. (2015). The humanistic and economic burden of providing care for a patient with schizophrenia. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(8), 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černe Kolarič, J., Plemenitaš Ilješ, A., Kraner, D., Gönc, V., Lorber, M., Mlinar Reljić, N., Fekonja, Z., & Kmetec, S. (2024). Long-term impact of community psychiatric care on quality of life amongst people living with schizophrenia: A systematic review. Healthcare, 12(17), 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, R., Dardi, A., Serafini, V., Amorado, M. J., Ferri, P., & Filippini, T. (2024). Psychoeducational intervention for caregivers of adolescents and young adults with psychiatric disorders: A 7-year systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13, 7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, D. G., Short, R., & Vitaliano, P. P. (1999). Predictors of burden and infectious illness in schizophrenia caregivers. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61(4), 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foldemo, A., Gullberg, M., Ek, A.-C., & Bogren, L. (2005). Quality of life and burden in parents of outpatients with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(2), 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisquini, P. D., Soares, M. H., Machado, F. P., Luis, M. A. V., & Martins, J. T. (2020). Relationship between well-being, quality of life and hope in family caregivers of schizophrenic people. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 73(Suppl. 1), e20190359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, Z., & Bowling, A. (2004). Quality of life from the perspectives of older people. Ageing & Society, 24(5), 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geriani, D. (2015). Burden of care on caregivers of schizophrenia patients: A correlation to personality and coping. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 9(3), VC01–VC04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P., Doley, M., & Verma, P. (2020). Comparative study on caregiver burden and their quality of life in caring patients of schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 8(2), 689–698. [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay, N., Vyas, N. S., Testa, R., Wood, S. J., & Pantelis, C. (2011). Age of onset of schizophrenia: Perspectives from structural neuroimaging studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37(3), 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, P. B., Macias, C., & Rodican, C. F. (2016). Does competitive work improve quality of life for adults with severe mental illness? Evidence from a randomized trial of supported employment. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 43(2), 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandón, P., Jenaro, C., & Lemos, S. (2008). Primary caregivers of schizophrenia outpatients: Burden and predictor variables. Psychiatry Research, 158(3), 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J., Caqueo-Urízar, A., & Kavanagh, D. J. (2005). Burden of care and general health in families of patients with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(11), 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A., Callaghan, P., & Lymn, J. S. (2015). Evaluation of the impact of a psycho-educational intervention for people diagnosed with schizophrenia and their primary caregivers in Jordan: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, L., Hawthorne, G., Farhall, J., O’Hanlon, B., & Harvey, C. (2015). Quality of life and social isolation among caregivers of adults with schizophrenia: Policy and outcomes. Community Mental Health Journal, 51(5), 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, C.-Y., Lu, H.-L., & Tsai, Y.-F. (2020). Caregiver burden and health-related quality of life among primary family caregivers of individuals with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. Quality of Life Research, 29(10), 2745–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issac, A., Nayak, S. G., Yesodharan, R., & Sequira, L. (2022). Needs, challenges, and coping strategies among primary caregivers of schizophrenia patient: A systematic review & meta-synthesis. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 41, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kate, N., Grover, S., Kulhara, P., & Nehra, R. (2013a). Positive aspects of caregiving and its correlates in caregivers of schizophrenia: A study from north India. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry, 23(2), 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kate, N., Grover, S., Kulhara, P., & Nehra, R. (2013b). Relationship of caregiver burden with coping strategies, social support, psychological morbidity, and quality of life in the caregivers of schizophrenia. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 6(5), 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kate, N., Grover, S., Kulhara, P., & Nehra, R. (2014). Relationship of quality of life with coping and burden in primary caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60(2), 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K., & Ghourmulla Alghamdi, A. (2020). Moderated moderation of gender and knowledge on the relation between burden of care and quality of life among caregivers of schizophrenia. Pharmacophore, 11(3), 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Khatimah, C. H., Adami, A., Abdullah, A., & Marthoenis. (2022). Quality of life, mental health, and family functioning of schizophrenia caregivers: A community-based cross-sectional study. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 14(1), e12467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y., Yamada, S., Kamijima, K., Kogushi, K., & Ikeda, S. (2024). Burden in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia, depression, dementia, and stroke in Japan: Comparative analysis of quality of life, work productivity, and qualitative caregiving burden. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulhara, P. (2012). Positive aspects of caregiving in schizophrenia: A review. World Journal of Psychiatry, 2(3), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S., Singh, P., Shah, R., & Soni, A. (2017). A study on assessment of family burden, quality of life and mental health in caregivers of patients with schizophrenia. International Archives of BioMedical and Clinical Research, 3, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. C., Yang, Y. K., Chen, P. S., Hung, N. C., Lin, S. H., Chang, F. L., & Cheng, S. H. (2006). Different dimensions of social support for the caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: Main effect and stress-buffering models. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 60(5), 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, A., Xu, C., Nicholas, S., Nicholas, J., & Wang, J. (2019). Quality of life in caregivers of a family member with serious mental illness: Evidence from China. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(1), 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J., Lambert, C. E., & Lambert, V. A. (2007). Predictors of family caregivers’ burden and quality of life when providing care for a family member with schizophrenia in the People’s Republic of China. Nursing & Health Sciences, 9(3), 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima-Rodríguez, J. S., de Medina-Moragas, A. J., Fernández-Fernández, M. J., & Lima-Serrano, M. (2022). Factors associated with quality of life in relatives of adults with serious mental illness: A systematic review. Community Mental Health Journal, 58(7), 1361–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-C. (2024). Caregiving experience associated with unpaid carers of persons with schizophrenia: A scoping review. Social Work in Mental Health, 22(2), 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, P. F., Lungu, C.-M., Ciobîcă, A., Balmus, I. M., Boloș, A., Dobrin, R., & Luca, A. C. (2023). Metacognition in schizophrenia spectrum disorders—Current methods and approaches. Brain Sciences, 13(7), 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margetić, B. A., Jakovljević, M., Furjan, Z., Margetić, B., & Boričević Maršanić, V. (2013). Quality of life of key caregivers of schizophrenia patients and association with kinship. Central European Journal of Public Health, 21(4), 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Carrasco, M., Fernández-Catalina, P., Domínguez-Panchón, A. I., Gonçalves-Pereira, M., González-Fraile, E., Muñoz-Hermoso, P., Ballesteros, J., & The EDUCA-III Group. (2016). A randomized trial to assess the efficacy of a psychoeducational intervention on caregiver burden in schizophrenia. European Psychiatry, 33, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marutani, T., Chhim, S., Nishio, A., Nosaki, A., & Fuse-Nagase, Y. (2020). Quality of life and its social determinants for patients with schizophrenia and family caregivers in Cambodia. PLoS ONE, 15(3), e0229643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2023). Evidence-based practice in nursing healthcare (5th ed.). Wolters. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, E., Iwasaki, M., Sakai, I., & Kamizawa, N. (2012). Sense of coherence and quality of life in family caregivers of persons with schizophrenia living in the community. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 26(4), 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, K., Sfetc, R., Currie, M., Lisy, K., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., & Mu, P.-F. (2020). Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). (2014). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: Treatment and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK). Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178 (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Neikrug, S. M. (2003). Worrying about a frightening old age. Aging & Mental Health, 7(5), 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, S., Vilaplana, M., Haro, J. M., Villalta-Gil, V., Martínez, F., Negredo, M. C., Casacuberta, P., Paniego, E., Usall, J., Dolz, M., Autonell, J., & NEDES Group. (2008). Do needs, symptoms or disability of outpatients with schizophrenia influence family burden? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(8), 612–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohaeri, J. U. (2001). Caregiver burden and psychotic patients’ perception of social support in a Nigerian setting. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 36(2), 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku-Boateng, Y. N., Kretchy, I. A., Aryeetey, G. C., Dwomoh, D., Decker, S., Agyemang, S. A., Tozan, Y., Aikins, M., & Nonvignon, J. (2017). Economic cost and quality of life of family caregivers of schizophrenic patients attending psychiatric hospitals in Ghana. BMC Health Services Research, 17(S2), 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Mckenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z., Li, T., Jin, G., & Lu, X. (2024). Caregiving experiences of family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia in a community: A qualitative study in Beijing. BMJ Open, 14(4), e081364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., Xu, R., Li, Y., Li, L., Song, L., & Xi, J. (2024). Dyadic effects of stigma on quality of life in people with schizophrenia and their family caregivers: Mediating role of patients’ perception of caregivers’ expressed emotion. Family Process, 63(3), 1655–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quah, S. (2014). Call for proposals. Sociology of Health & Illness, 36(4), 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajji, T. K., Ismail, Z., & Mulsant, B. H. (2009). Age at onset and cognition in schizophrenia: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 195(4), 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribé, J. M., Salamero, M., Pérez-Testor, C., Mercadal, J., Aguilera, C., & Cleris, M. (2018). Quality of life in family caregivers of schizophrenia patients in Spain: Caregiver characteristics, caregiving burden, family functioning, and social and professional support. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 22(1), 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S., Chant, D., Welham, J., & McGrath, J. (2005). A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Medicine, 2(5), e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R., & Sherwood, P. R. (2008). Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. The American Journal of Nursing, 108(Suppl. S9), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H. J., Brożek, J., Guyatt, G., & Oxman, A. D. (Eds.). (2013). GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group. Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Shiraishi, N., & Reilly, J. (2019). Positive and negative impacts of schizophrenia on family caregivers: A systematic review and qualitative meta-summary. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(3), 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S., & Balakrishnan, S. (2023). Family caregiving in schizophrenia: Do stress, social support and resilience influence life satisfaction?—A quantitative study from India. Social Work in Mental Health, 21(1), 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S., Balakrishnan, S., & Ilangovan, S. (2017). Psychological distress, perceived burden and quality of life in caregivers of persons with schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health, 26(2), 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, P., & Matheiken, S. T. (2010). Caregivers in schizophrenia: A cross cultural perspective. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 32(1), 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R., Keshavan, M. S., & Nasrallah, H. A. (2008). Schizophrenia, “Just the Facts”: What we know in 2008. Schizophrenia Research, 100(1–3), 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thara, R., Kamath, S., & Kumar, S. (2003). Women with schizophrenia and broken marriages—Doubly disadvantaged? Part II: Family perspective. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 49(3), 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group. (1998). Development of the world health organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine, 28(3), 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristiana, R. D., Triantoro, B., Nihayati, H. E., Yusuf, A., & Abdullah, K. L. (2019). Relationship Between caregivers’ burden of schizophrenia patient with their quality of life in indonesia. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health, 6(2), 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2013). Psychiatric comorbidity among adults with schizophrenia: A latent class analysis. Psychiatry Research, 210(1), 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukpong, D., & Ibigbami, O. (2021). Sizofreni ve bipolar duygulanim bozuklugu hastalarina bakim verenlerin yasam kalitelerinin karsilastirilmasi: Bir guneybati nijerya calismasi. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 32(1), 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, R., Haider, A., Ramzan, Z., & Mansoori, S. (2021). Quality of life satisfaction among caregivers of schizophrenic patients. Annals of Abbasi Shaheed Hospital and Karachi Medical & Dental College, 26(2), 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadher, S., Desai, R., Panchal, B., Vala, A., Ratnani, I. J., Rupani, M. P., & Vasava, K. (2020). Burden of care in caregivers of patients with alcohol use disorder and schizophrenia and its association with anxiety, depression and quality of life. General Psychiatry, 33(4), e100215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Os, J., & Kapur, S. (2009). Schizophrenia. The Lancet, 374(9690), 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volanen, S. M., Lahelma, E., Silventoinen, K., & Suominen, S. (2004). Factors contributing to sense of coherence among men and women. European Journal of Public Health, 14(3), 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Z., Meng, X.-D., Zhang, T.-M., Weng, X., Li, M., Luo, W., Huang, Y., Thornicroft, G., & Ran, M.-S. (2023). Affiliate stigma and caregiving burden among family caregivers of persons with schizophrenia in rural China. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 69(4), 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winahyu, K. M., Hemchayat, M., & Charoensuk, S. (2015). Factors Affecting Quality of Life among Family Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia in Indonesia. Journal of Health Research, 29(Suppl. 1), S77–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerriah, J., Tomita, A., & Paruk, S. (2022). Surviving but not thriving: Burden of care and quality of life for caregivers of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and comorbid substance use in South Africa. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 16(2), 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZamZam, R., Midin, M., Hooi, L. S., Yi, E. J., Ahmad, S. N., Azman, S. F., Borhanudin, M. S., & Radzi, R. S. (2011). Schizophrenia in Malaysian families: A study on factors associated with quality of life of primary family caregivers. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 5(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zauszniewski, J. A., Bekhet, A. K., & Suresky, M. J. (2008). Factors associated with perceived burden, resourcefulness, and quality of life in female family members of adults with serious mental illness. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 14(2), 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Year | Country Study Design n, Mean (SD) Age, % of Female Caregivers Patients’ Setting | QoL Measure | Main Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Factors of Caregivers | Patient’s Sociodemographic and Clinical Factors | Psychological Factors of Caregivers | |||

| (Ribé et al., 2018) | Spain Cross-sectional n = 100, 60.1 (11.7), 82% Outpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ⇑ age—⇓ QoL (physical and social domains). ♀—⇓ QoL (physical and social domains). ⇑ education—⇑ QoL (social and environmental domains). Employment—⇑ QoL (physical domain). Living with the patient—⇓ QoL (social and environmental domains). | Early-onset schizophrenia in patients—⇓ QoL | ⇑ caregiving burden—⇓ QoL in all domains. Strong social support—⇑ psychological, social, and environmental QoL domains. ⇑ Family APGAR scores—⇑ QoL. |

| (Stanley et al., 2017) | India Cross-sectional n = 75, 49.4, 37.5% Inpatients | S-CGQoL | No significant correlation was found between caregiver age and QoL. ♂—⇑ QoL (mean = 93.9) than ♀ (mean = 91.2). ⇓ income—⇓ QoL. | ⇑ severe symptoms—⇓ QoL (p < 0.05). | ⇑ caregiver burden—⇓ QoL across all domains (r = −0.34, p < 0.01). |

| (Kate et al., 2014) | India Cross-sectional n = 100, 46 (11.6), 35% Outpatients and inpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | Rural background—⇑ QoL in the social health domain. | Clinical variables of the patients, including symptom severity and illness duration, showed no significant correlations with caregivers’ QoL. | Coping styles: seeking social support—⇓ QoL; collusion—⇓ QoL (physical health, social relationships, and environmental domains); and coercion—⇓ QoL (general health and environmental domains). ⇑ spirituality, religiousness, and personal beliefs—⇑ QoL. |

| (Margetić et al., 2013) | Croatia Case–control n = 138, 52.6 (14.4), 63.8% Outpatients | QLESQ-SF | ⇑ age—⇓ QoL (r = −0.464, p = 0.0001). Parents and children of patients—⇓ QoL than siblings (F = 3.567, p = 0.031). Single, divorced, or widowed caregivers—⇓ QoL. | QoL—no correlation with PANSS scores, GAF scores, length of illness, or number of hospitalizations. | n.s. |

| (Mizuno et al., 2012) | Japan Cross-sectional n = 34, 63.3 (13.3), 79.4% Outpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ⇑ age—⇑ psychological and environment QoL scores. Living with patients—⇓ psychological and environmental QoL. | n.s. | ⇑ sense of coherence—⇓ QoL. |

| (Quah, 2014) | Singapore Cross-sectional n = 47, no mean age, 55.3% Patients’ setting n.s. | WHOQoL-Bref | n.s. | n.s. | Caregivers providing more than 6 h daily (role overload)—⇓ QoL. ⇑ role distress—⇓ QoL across all domains. |

| (Kate et al., 2013b) | India Cross-sectional n = 100, 45.9 (11.6), 35% Outpatients and inpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | n.s. | n.s. | ⇑ caregiver burden, especially in the tension domain—⇓ QoL across all domains. |

| (Stanley & Balakrishnan, 2023) | India Cross-sectional n = 75, 46.24, 62.7% Inpatients | The Satisfaction with Life Scale | n.s. | n.s. | Stress had significant direct effects on resilience (effect = 1.39, p < 0.01) and QoL (effect = 0.70, p < 0.001). Resilience mediated the relationship between stress and QoL (effect = 0.09, p < 0.01). Social support did not moderate the relationship between stress and resilience (p > 0.05) but was (+) correlated with resilience and QoL. |

| (Khatimah et al., 2022) | Indonesia Cross-sectional n = 106, 43, 85.8% Outpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ⇑ age—⇓ QoL (in the physicological and environmental domains). Higher education—⇓ QoL (in the psychological and environmental domains (β = −0.775, p = 0.005)). Employed caregivers—⇑ QoL (in the environmental and psychological domains (β = 1.869, p = 0.008, β = 1.112, p = 0.035)). | General functioning of patients—⇑ QoL. | ⇑ stress—⇓ QoL in all domains: physical health (β = −0.134, p = 0.004); environment (β = −0.134, p = 0.004); and overall QoL (β = −0.224, p = 0.033). Anxiety and depression (−) impacted QoL scores. Environment: depression (β = −0.156, p = 0.005); anxiety (β = −0.149, p = 0.001). Social relationships: depression (β = −0.068, p = 0.012); overall QOL (β = −0.232, p = 0.023; β = −0.335, p = 0.004) |

| (Tristiana et al., 2019) | Indonesia Cross-sectional n = 222, 44.05 (9.61), 31.1% Outpatients | S-CGQoL | ♂—⇑ QoL (p = 0.003). Married caregivers—⇑ QoL (p = 0.045). Longer caregiving duration—no significant correlation with QoL. | n.s. | ⇑ caregiving burden—⇓ QoL (r = −0.434, p < 0.001). |

| (Francisquini et al., 2020) | Brazil Cross-sectional n = 117, 56.7 (15.7), 74.4% Outpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ⇑ age—⇓ QoL, particularly in social relationships (r = −0.401, p < 0.01). | n.s. | ⇑ hope—⇓ QoL in all domains (r = 0.342–0.595, p < 0.05). |

| (Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2016b) | Bolivia, Chile, Peru Cross-sectional n = 253, 54.7 (14.4), 67.7% Outpatients | S-CGQoL | n.s. | ⇑ neurocognitive deficits—⇓ QoL (r = −0.32, p < 0.05). | n.s. |

| (Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2016a) | Bolivia, Chile, Peru Cross-sectional n = 253, 54.7 (14.4), 67.7% Outpatients | S-CGQoL | ♀—⇓ QoL in the material burden dimension (β = −0.15, p < 0.05). Mothers—⇓ QoL in the psychological and physical well-being and psychological burden and daily life domains. Aymara ethnicity—⇓ QoL scores in the relationships with family (β = −0.17, p < 0.05) and material burden (β = −0.24, p < 0.01) dimensions. ⇑ income—⇑ QoL in the material burden domain (β = 0.25, p < 0.01). | ⇑ severe symptoms—⇓ QoL in psychological and physical well-being (β = −0.29, p < 0.01) and psychological burden and daily life (β = −0.28, p < 0.01). Earlier onset of schizophrenia—⇓ QoL. Unawareness of mental disorder—⇓ QoL (β = −0.23, p < 0.001). ⇑ patients age—⇑ QoL in the material burden dimension (β = 0.19, p < 0.05). | ⇑ subjective burden—⇓ QoL (in psychological and physical well-being). Religious Involvement—not significantly associated with overall QoL, except for a (-) correlation in the psychological and physical well-being domains (β = −0.17, p < 0.05). |

| (Khan & Ghourmulla Alghamdi, 2020) | Saudi Arabia Cross-sectional n = 150, 44.7 (13.1), 65.3% Patients’ setting n.s. | S-CGQoL | There is no significant difference between gender means. Higher knowledge about schizophrenia—⇑ QoL (r = 0.236, p < 0.01). The interaction between knowledge and gender significantly affected QoL (three-way interaction R2 change = 3.64%, F = 7.24, p < 0.01). | n.s. | ⇑ caregiving burden—⇓ QoL (r = −0.43, p < 0.01). |

| (Geriani, 2015) | India Cross-sectional n = 110, 43.82, 73% Patients’ setting n.s. | WHOQoL-Bref | Caregivers from nuclear families—⇑ environmental QoL compared to those from joint families (p < 0.01). | n.s. | ⇑ burden levels—⇓ QoL in the physical, psychological, social, and environmental domains (p < 0.05). Good coping strategies—⇑ environmental QoL (p = 0.037). |

| (Marutani et al., 2020) | Cambodia Cross-sectional n = 59 Outpatients | SF-12 v1 | ♂—⇓ QoL (mental health component). ⇓ household economic status (insufficient to meet basic needs)—⇓ QoL. Employed caregivers—⇑ QoL. Caregivers with chronic physical disease—⇓ QoL (physical component). | The severity of the patient’s illness, the caregiving duration, and DUP—no direct correlation with the caregiver’s QoL. | n.s. |

| (Ukpong & Ibigbami, 2021) | Nigeria Cross-sectional n = 100, 56.13 (12.99), 63% Outpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ⇑ age—⇓ QoL (in all domains). Married caregivers—⇓ QoL in the psychological health, social relationships, and environmental domains. ⇑ caregiving duration—⇓ QoL (in the physical, psychological, and social domains. | ⇑ illness duration—⇓ QoL (in the physical, psychological, and environmental domains). Employed patient—⇑ caregiver QoL in the physical domain. ⇑ patient’s age—⇓ QoL (physical domain). | ⇑ caregiving burden—⇓ QoL across the psychological, social, and environmental domains. Depressive and anxiety symptoms—⇓ QoL in the psychological, social, and environmental domains. |

| (Wang et al., 2023) | China Cross-sectional n = 253, 47.43% Patients’ setting n.s. | WHOQoL-Bref | ♂—⇑ QoL score (mean = 85.14, SD = 11.27) compared to ♀(mean = 82.35, SD = 10.09). | n.s. | ⇑ levels of affiliate stigma—⇓ QoL. ⇑ caregiving burden—⇓ QoL (in all domains). |

| (Opoku-Boateng et al., 2017) | Ghana Cross-sectional n = 444, 47, 57% Outpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ♀—⇓ QoL. Caregivers with tertiary education—⇑⇑ QoL. Married caregivers—⇑ QoL. Close proximity to the psychiatric service—⇑ overall QoL. Receiving support from family in caregiving—⇑ physical and psychological QoL. | n.s. | Depression, anxiety, and stress levels—⇓ QoL. ⇑ caregiving burden—⇓ QoL. |

| (Yerriah et al., 2022) | South Africa Cross-sectional n = 101, 53.1 (14.2), 82.2% Outpatients and inpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ⇑ age—⇓ QoL (in the physical and social domains). ⇑ education levels—⇑ QoL (in the physical and social domains). Being married—⇑ QoL in the social domain score. ⇑ income—⇑ QoL in the physical, social, and environmental domains. | Patient with comorbidity—⇓ QoL physical domain. | ⇑ caregiving burden—⇓ QoL (in all domains). |

| (Boyer et al., 2012) | France, Chile Cross-sectional French: n = 245, 60.6, 67.1% Chilean: n = 41, 54.3, 63.4% Outpatients | SF-36 | Mothers—⇓⇓ QoL across all domains. Living with the patient—⇓ QoL mental composite domain. Employed caregivers—⇑ QoL in the physical composite domain. ⇑ age—⇓ QoL in the physical composite domain. | n.s. | n.s. |

| (Kate et al., 2013a) | India Cross-sectional n = 100, 46 (12), 35% Outpatients and inpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | No significant correlations were found between sociodemographic factors and caregiver QoL. | n.s. | ⇑ positive caregiving experience—⇑ QoL in all domains. ⇑ scores in spirituality, religiousness, and personal beliefs—⇑ QoL. |

| (Li et al., 2007) | China Cross-sectional n = 96, 47 (12), 57.3% Inpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ⇑ age—⇓ QoL (physical health and psychological domains). ⇑ household income—⇑⇑ QoL (in the physical and psychological domains). ⇑ education levels—⇑ psychological, social, and environmental QoL. ⇑ caregiver physical health—the strongest predictor of ⇑ QoL. | ⇑ illness duration and more hospitalizations of the patient—⇓ QoL. | n.s. |

| (ZamZam et al., 2011) | Malaysia Cross-sectional n = 117, 47 (12), 52.1% Outpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | Parents—⇓ QoL in the physical health domain. Higher education—⇑ QoL. Employed caregivers—⇑ QoL (in the physical and psychological domains). ♀—⇓ QoL in the physical domain. ⇑ caregiver health—⇑ QoL in the physical, psychological, and environmental domains. | ⇑ illness duration and multiple hospitalizations—⇓ QoL. Later illness onset—⇑ social relationships QoL. Caregivers of patients attending day care programs—⇓ QoL across all domains. ⇑ severity of symptoms—⇓ QoL in the physical and environmental domains. Caregivers of employed patients or of patients with higher educational levels—⇑ QoL in the psychological domain. | ⇑ caregiver stress levels—⇓ QoL in the psychological and environmental domains. |

| (Vadher et al., 2020) | India Cross-sectional n = 50, 46.7 (14.2), 40% Outpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ♀—⇓ QoL in the environmental domain. | n.s. | ⇑ caregiver burden of care—⇓ QoL in all domains. |

| (Usman et al., 2021) | Pakistan Cross-sectional n = 150, 45.36 (3.85) 36.7% Outpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | Caregivers aged 31–60 years—⇑ QoL, compared to those aged < 30 years or > 60 years. Employed caregivers—⇑ QoL (p = 0.040). ⇑ household income—⇑⇑ QoL. Parents—⇑ QoL scores compared to spouse, offspring, sibling, or other. Caregivers with chronic physical illnesses—⇓⇓ QoL. Caregivers of patients aged >30 years—⇑ QoL compared to caregivers of younger patients (p < 0.001). | n.s. | n.s. |

| (Hsiao et al., 2020) | China Cross-sectional n = 157, 54.94 (2.22) 63.7% Inpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ⇑ age—⇓ QoL (in the physical and psychological domains). ⇓ education—⇓ QoL. ⇓ income—⇓ QoL in all domains. Employed caregivers—⇑ physical, psychological, and social QoL. Parents—⇓ QoL scores. | ⇑ psychiatric symptom severity—⇓ QoL in all domains. | ⇑ mutuality score (better caregiver–patient relationships)—⇑ QoL across all domains. Effective family coping strategies—⇑ QoL across all domains. |

| (Winahyu et al., 2015) | Indonesia Cross-sectional n = 137, 47.36 (12.22) 74.45% Outpatients | S-CGQoL | Employed caregivers—⇑ QoL (Beta = 0.15, p = 0.024). Gender, period of being a caregiver, and health status—no significant correlation with QoL. | n.s. | ⇑ caregiver burden of care—⇓ QoL (Beta = −0.39, p < 0.001). ⇑ perceived social support—⇑⇑ QoL (Beta = 0.40, p < 0.001). |

| (Peng et al., 2024) | China Longitudinal n = 161, 66.32 (10.52) 49.07% Outpatients | WHOQoL-Bref | ⇑ age—⇓ QoL (in the physical and psychological domains). ⇑ education levels—⇑ QoL (in the psychological domain). ⇑ income—⇑ QoL. | ⇑ psychiatric symptom severity—⇓ QoL in all domains. | ⇑ expressed emotion—⇓⇓ QoL. ⇑ internalized stigma—⇓⇓ QoL |

| (Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2016a) | Bolivia, Chile, Peru Cross-sectional n = 253, 54.7 (14.4), 67% Outpatients | S-CGQoL | Being female, older, unemployed, Aymara, and having a low family income—⇓ QoL levels. | n.s. | Greater perception of patient’s neurocognitive and social cognitive deficits—⇓ QoL in family relationships. |

| (Ghosh et al., 2020) | India Cross-sectional n = 35, 42.5 (12.1), 37.1% Patients’ setting n.s. | WHOQoL-Bref | n.s. | n.s. | ⇑ caregiver burden of care—⇓ QoL in the psychological domain (p = 0.040) and the environmental domain (p = 0.030). |

| Article | Study Design | Question Number | Overall Score | Methodological Quality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| (Ribé et al., 2018) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Stanley et al., 2017) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Kate et al., 2014) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 5 62.5% | moderate |

| (Margetić et al., 2013) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 5 62.5% | moderate |

| (Mizuno et al., 2012) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Quah, 2014) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Kate et al., 2013b) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Stanley & Balakrishnan, 2023) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Khatimah et al., 2022) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Tristiana et al., 2019) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Francisquini et al., 2020) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2016b) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2016a) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Khan & Ghourmulla Alghamdi, 2020) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Geriani, 2015) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Marutani et al., 2020) | cross-sectional | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 87.5% | high |

| (Ukpong & Ibigbami, 2021) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Wang et al., 2023) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 5 62.5% | moderate |

| (Opoku-Boateng et al., 2017) | cross-sectional | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 87.5% | high |

| (Yerriah et al., 2022) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Boyer et al., 2012) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Kate et al., 2013a) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 5 62.5% | moderate |

| (Li et al., 2007) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (ZamZam et al., 2011) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Vadher et al., 2020) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Usman et al., 2021) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Hsiao et al., 2020) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Winahyu et al., 2015) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8 100% | excellent |

| (Peng et al., 2024) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2016b) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

| (Ghosh et al., 2020) | cross-sectional | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 6 75% | moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gagiu, C.; Dionisie, V.; Manea, M.C.; Covaliu, A.; Vlad, A.D.; Tupu, A.E.; Manea, M. Quality of Life in Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review of the Impact of Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychological Factors. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050684

Gagiu C, Dionisie V, Manea MC, Covaliu A, Vlad AD, Tupu AE, Manea M. Quality of Life in Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review of the Impact of Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychological Factors. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):684. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050684

Chicago/Turabian StyleGagiu, Corina, Vlad Dionisie, Mihnea Costin Manea, Anca Covaliu, Ana Diana Vlad, Ancuta Elena Tupu, and Mirela Manea. 2025. "Quality of Life in Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review of the Impact of Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychological Factors" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050684

APA StyleGagiu, C., Dionisie, V., Manea, M. C., Covaliu, A., Vlad, A. D., Tupu, A. E., & Manea, M. (2025). Quality of Life in Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review of the Impact of Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Psychological Factors. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 684. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050684