UMAI-WINGS: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Implementing mHealth Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Intervention in Reducing Intimate Partner Violence Among Women from Key Affected Populations in Kazakhstan Using a Community-Based Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global and National Overview of IPV

1.2. IPV and Risk Factors in Key Affected Populations (KAPs)

1.3. Multiple Risk Factors Drive IPV Among KAPs

1.4. Structural Barriers in Kazakhstan

- (1)

- Lack of surveillance data: national household surveys exclude KAPs, preventing the timely identification of IPV hotspots;

- (2)

- Fragmented services: there is little coordination between mainstream IPV services and programs serving women from KAPs;

- (3)

- Stigma and discrimination: widespread blame of KAPs for the violence they experience inhibits access to support;

- (4)

- Limited community engagement: few mechanisms exist to mobilize stakeholders for inclusive policy and service development.

1.5. Study Rationale and Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Intervention: UMAI-WINGS Community Coordinated Response Model and Role of the Community Action and Accountability Board (CAAB)

- (1)

- Developing a shared charter: at the outset, CAAB members collaboratively created a shared vision and operating agreement to guide their work in addressing IPV/GBV in the community.

- (2)

- Reviewing local IPV/GBV data: the CAAB reviewed existing data on the prevalence and dynamics of IPV/GBV among KAPs in their communities, fostering shared understanding of the magnitude and complexity of the problem.

- (3)

- Service mapping and gap analysis: CAAB members conducted a comprehensive mapping of local IPV/GBV-related services, identified service gaps (e.g., lack of inclusive shelters, legal aid, or mental health care), and pinpointed structural barriers (e.g., stigma, discrimination, exclusionary policies, and lack of transportation) that prevent KAP women from accessing care.

- (4)

- Network building across sectors: the CAAB facilitated the development of a cross-sectoral network to enhance service coordination, streamline referrals, and strengthen the safety net for women experiencing IPV.

- (5)

- Capacity building and training: CAAB members were trained on the UMAI-WINGS intervention content and implementation procedures; trainings also covered how to interpret and use UMAI-WINGS data for planning and advocacy, promoting evidence-informed local responses to IPV/GBV.

- (6)

- Participatory adaptation: CAAB feedback was central to adapting the original WINGS model; CAABs and KAP representatives informed ethical adjustments, content refinement, and cultural tailoring, especially regarding safety planning components for women engaged in sex work and transgender women, where the highest risk and greatest barriers were identified.

2.4. Community Engagement and Capacity Building in Intervention Trial

2.5. Measurement

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

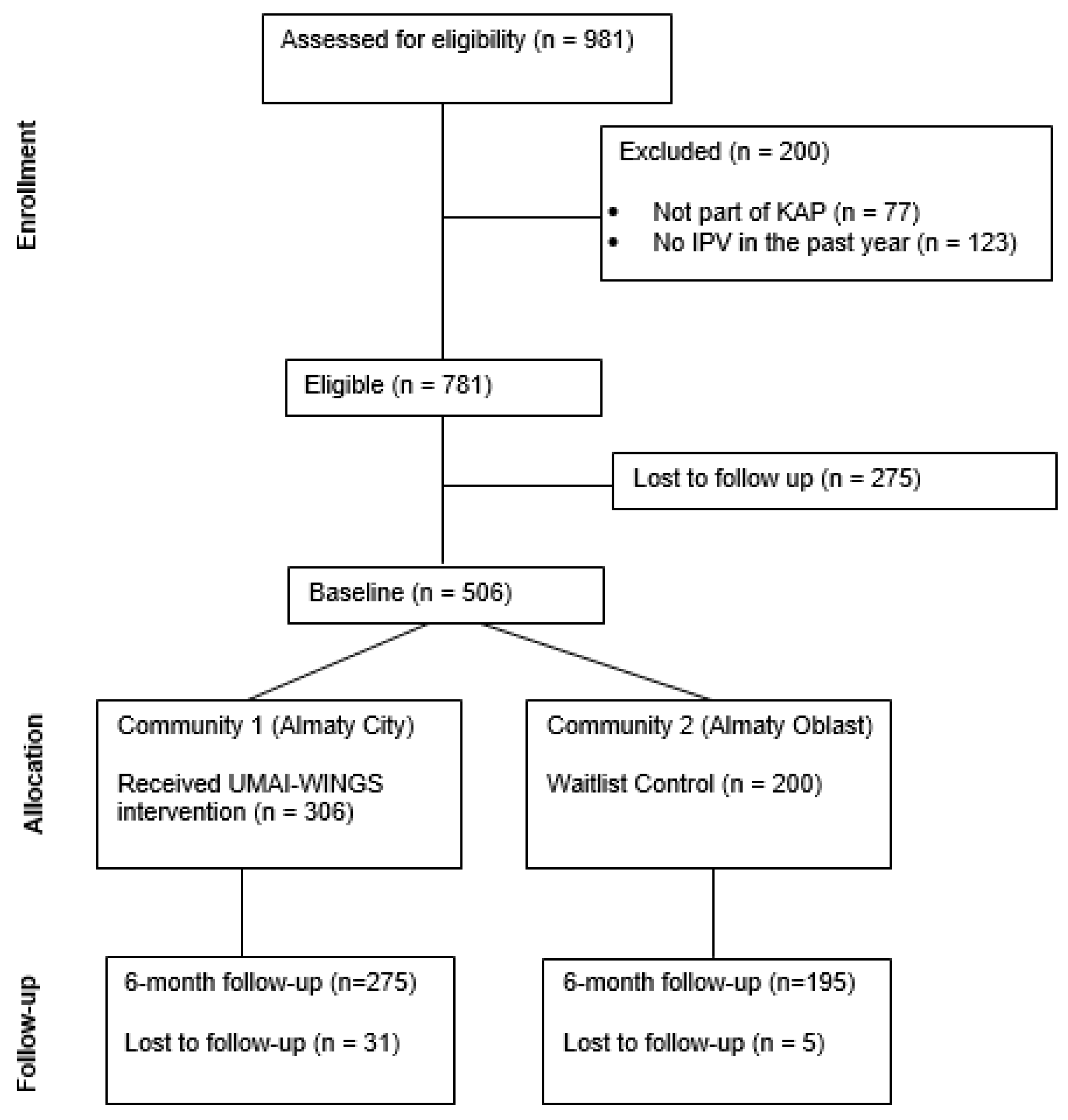

3.1. Sample Flow and Retention

3.2. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.3. Baseline Group Comparisons

3.4. IPV Outcomes

3.5. Acceptability

3.6. Safety

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Study

4.2. Strength and Implications of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, J. B., Lent, B., Schmidt, G., & Sas, G. (2000). Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. The Journal of Family Practice, 49(10), 896–903. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. J., Lowe, H., Gibbs, A., Smith, C., & Mannell, J. (2023). High-risk contexts for violence against women: Using latent class analysis to understand structural and contextual drivers of intimate partner violence at the national level. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(1–2), 1007–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CABAR.Asia. (n.d.). What’s wrong with women’s crisis centres in Kazakhstan? Available online: https://cabar.asia/en/what-s-wrong-with-women-s-crisis-centres-in-kazakhstan (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- El-Bassel, N., Mukherjee, T. I., Stoicescu, C., Starbird, L. E., Stockman, J. K., Frye, V., & Gilbert, L. (2022). Intertwined epidemics: Progress, gaps, and opportunities to address intimate partner violence and HIV among key populations of women. The Lancet HIV, 9(3), e202–e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, L., Goddard-Eckrich, D., Hunt, T., Ma, X., Chang, M., Rowe, J., McCrimmon, T., Johnson, K., Goodwin, S., Almonte, M., & Shaw, S. A. (2016). Efficacy of a computerized intervention on HIV and intimate partner violence among substance-using women in community corrections: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health, 106(7), 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, L., Jiwatram-Negrón, T., Nikitin, D., Rychkova, O., McCrimmon, T., Ermolaeva, I., Sharonova, N., Mukambetov, A., & Hunt, T. (2017). Feasibility and preliminary effects of a screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment model to address gender-based violence among women who use drugs in Kyrgyzstan: Project WINGS (Women Initiating New Goals of Safety). Drug and Alcohol Review, 36(1), 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, L., Marotta, P. L., Goddard-Eckrich, D., Richer, A., Akuffo, J., Hunt, T., Wu, E., & El-Bassel, N. (2022). Association between multiple experiences of violence and drug overdose among Black women in community supervision programs in New York City. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(23–24), NP21502–NP21524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, L., Raj, A., Hien, D., Stockman, J., Terlikbayeva, A., & Wyatt, G. (2015a). Targeting the SAVA (substance abuse, violence, and AIDS) syndemic among women and girls: A global review of epidemiology and integrated interventions. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 69(Suppl. 2), S118–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, L., Shaw, S. A., Goddard-Eckrich, D., Chang, M., Rowe, J., McCrimmon, T., Almonte, M., Goodwin, S., & Epperson, M. (2015b). Project WINGS (Women Initiating New Goals of Safety): A randomised controlled trial of a screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) service to identify and address intimate partner violence victimisation among substance-using women receiving community supervision. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 25(4), 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, L., Bhowmik, J., Apputhurai, P., & Nedeljkovic, M. (2023). Factors and consequences associated with intimate partner violence against women in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLOS ONE, 18(11), e0293295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Rights Watch. (2024, April 23). Kazakhstan: New law to protect women improved, but incomplete. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/04/23/kazakhstan-new-law-protect-women-improved-incomplete (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Jiwatram-Negrón, T., El-Bassel, N., Primbetova, S., & Terlikbayeva, A. (2018). Gender-based violence among HIV-positive women in Kazakhstan: Prevalence, types, and associated risk and protective factors. Violence Against Women, 24(13), 1570–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, T. I., Terlikbayeva, A., McCrimmon, T., Primbetova, S., Mergenova, G., Benjamin, S., Witte, S., & El-Bassel, N. (2023). Association of gender-based violence with sexual and drug-related HIV risk among female sex workers who use drugs in Kazakhstan. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 34(10), 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M., Ellsberg, M., Balogun, A., & Garcia-Moreno, C. (2021). Risk and protective factors for GBV among women and girls living in humanitarian settings: Systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussabekova, S. A., Mkhitaryan, X. E., & Abdikadirova, K. R. (2024). Domestic violence in Kazakhstan: Forensic-medical and medical-social aspects. Forensic Science International: Reports, 9, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ORDA. (2024). “Kazakhstan police received over 100,000 domestic violence complaints this year”, 20 December 2024. Available online: https://en.orda.kz/kazakhstan-police-received-over-100000-domestic-violence-complaints-this-year-4234/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Peitzmeier, S. M., Malik, M., Kattari, S. K., Marrow, E., Stephenson, R., Agénor, M., & Reisner, S. L. (2020). Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and correlates. American Journal of Public Health, 110(9), e1–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabri, B., & Young, A. M. (2022). Contextual factors associated with gender-based violence and related homicides perpetrated by partners and in-laws: A study of women survivors in India. Health Care for Women International, 43(7–8), 784–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senem Sel, S. (2024). International Relations Review. Domestic Violence in Kazakhstan: Calls for Criminalization. May 2. Available online: https://www.irreview.org/articles/2024/4/29/domestic-violence-in-kazakhstan-calls-for-criminalization (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney-McCoy, S., & Sugarman, D. B. (1996). The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. (n.d.). HIV status: Challenges that women face. Available online: https://www.undp.org/kazakhstan/stories/hiv-status-challenges-women-face (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- World Bank Group. (2024). Women, Business and the Law 2024. Available online: https://wbl.worldbank.org/content/dam/documents/wbl/2024/pilot/WBL24-2-0-Kazakhstan.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

| Univariable | Bivariable Comparisons | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample (n = 458) | Almaty Oblast—Control (n = 194) | Almaty City—Intervention (n = 264) | p-Value | |

| Age | 36.7 (9.0) | 36.1 (9.0) | 37.0 (9.0) | 0.285 |

| Nationality | ||||

| Kazakh | 169 (36.9%) | 89 (45.9%) | 80 (30.3%) | <0.001 |

| Russian | 142 (31.0%) | 38 (19.6%) | 104 (39.4%) | |

| Other | 147 (32.1%) | 67 (34.5%) | 80 (30.3%) | |

| Education | ||||

| 9th grade or lower | 101 (22.1%) | 37 (19.1%) | 64 (24.2%) | 0.258 |

| Secondary education | 145 (31.7%) | 57 (29.4%) | 88 (33.3%) | |

| High school | 161 (35.2%) | 77 (39.7%) | 84 (31.8%) | |

| Bachelor’s or more | 51 (11.1%) | 23 (11.9%) | 28 (10.6%) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 46 (10.0%) | 12 (6.2%) | 34 (12.9%) | 0.019 |

| Not married/other | 412 (89.96%) | 182 (93.8%) | 230 (87.1%) | |

| Homelessness (past year) | 186 (40.6%) | 104 (53.6%) | 82 (31.1%) | <0.001 |

| Food insecurity (past year) | 254 (55.5%) | 133 (68.6%) | 121 (45.8%) | <0.001 |

| Income (USD) | 412.22 (472.34) | 412.53 (399.91) | 411.99 (519.92) | 0.990 |

| Key affected population | ||||

| Sex workers | 335 (73.1%) | 163 (84.0%) | 172 (65.2%) | <0.001 |

| Persons who use drugs | 266 (58.1%) | 146 (75.3%) | 120 (45.5%) | <0.001 |

| Persons living with HIV | 140 (30.6%) | 34 (17.5%) | 106 (40.2%) | <0.001 |

| Univariable | Bivariable Comparisons | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample (n = 458) | Almaty Oblast—Control (n = 194) | Almaty City—Intervention (n = 264) | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | |

| Psychological | ||||

| Baseline | 296 (64.6%) | 127 (65.5%) | 169 (64.0%) | 0.97 (0.83, 1.15) |

| Six-month follow-up | 256 (55.9%) | 146 (75.3%) | 110 (41.7%) | 0.56 (0.48, 0.66) |

| Sexual | ||||

| Baseline | 288 (62.9%) | 123 (63.4%) | 165 (62.5%) | 0.98 (0.84, 1.16) |

| Six-month follow-up | 252 (55.0%) | 137 (70.6%) | 115 (43.6%) | 0.63 (0.54, 0.74) |

| Physical | ||||

| Baseline | 267 (58.3%) | 130 (67.0%) | 137 (51.9%) | 0.77 (0.66, 0.90) |

| Six-month follow-up | 211 (46.1%) | 143 (73.7%) | 68 (25.8%) | 0.30 (0.23, 0.40) |

| Multivariable Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| aRR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Past 6-month intimate partner violence | ||

| Psychological | 0.77 (0.69, 0.86) | <0.0001 |

| Sexual | 0.73 (0.63, 0.85) | <0.0001 |

| Physical | 0.71 (0.63, 0.80) | <0.0001 |

| Multivariable Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| aRR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Past 6-month psychological IPV | ||

| Persons living with HIV | 1.05 (0.79, 1.40) | 0.748 |

| Persons who use drugs | 1.23 (0.92, 1.63) | 0.160 |

| Sex workers | 1.03 (0.78, 1.37) | 0.833 |

| Past 6-month sexual IPV | ||

| Persons living with HIV | 0.91 (0.71, 1.18) | 0.478 |

| Persons who use drugs | 1.07 (0.78, 1.48) | 0.678 |

| Sex workers | 1.06 (0.79, 1.41) | 0.697 |

| Past 6-month physical IPV | ||

| Persons living with HIV | 1.03 (0.81, 1.32) | 0.796 |

| Persons who use drugs | 0.95 (0.74, 1.22) | 0.690 |

| Sex workers | 0.97 (0.74, 1.28) | 0.838 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Terlikbayeva, A.; Primbetova, S.; Gatanaga, O.S.; Chang, M.; Rozental, Y.; Nurkatova, M.; Baisakova, Z.; Bilokon, Y.; Karan, S.E.; Dasgupta, A.; et al. UMAI-WINGS: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Implementing mHealth Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Intervention in Reducing Intimate Partner Violence Among Women from Key Affected Populations in Kazakhstan Using a Community-Based Approach. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 641. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050641

Terlikbayeva A, Primbetova S, Gatanaga OS, Chang M, Rozental Y, Nurkatova M, Baisakova Z, Bilokon Y, Karan SE, Dasgupta A, et al. UMAI-WINGS: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Implementing mHealth Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Intervention in Reducing Intimate Partner Violence Among Women from Key Affected Populations in Kazakhstan Using a Community-Based Approach. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):641. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050641

Chicago/Turabian StyleTerlikbayeva, Assel, Sholpan Primbetova, Ohshue S. Gatanaga, Mingway Chang, Yelena Rozental, Meruert Nurkatova, Zulfiya Baisakova, Yelena Bilokon, Shelly E. Karan, Anindita Dasgupta, and et al. 2025. "UMAI-WINGS: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Implementing mHealth Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Intervention in Reducing Intimate Partner Violence Among Women from Key Affected Populations in Kazakhstan Using a Community-Based Approach" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 641. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050641

APA StyleTerlikbayeva, A., Primbetova, S., Gatanaga, O. S., Chang, M., Rozental, Y., Nurkatova, M., Baisakova, Z., Bilokon, Y., Karan, S. E., Dasgupta, A., & Gilbert, L. (2025). UMAI-WINGS: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Implementing mHealth Intimate Partner Violence Prevention Intervention in Reducing Intimate Partner Violence Among Women from Key Affected Populations in Kazakhstan Using a Community-Based Approach. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 641. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050641