3. Results

3.1. Correlations of Courage Measures and the Four Predictors

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

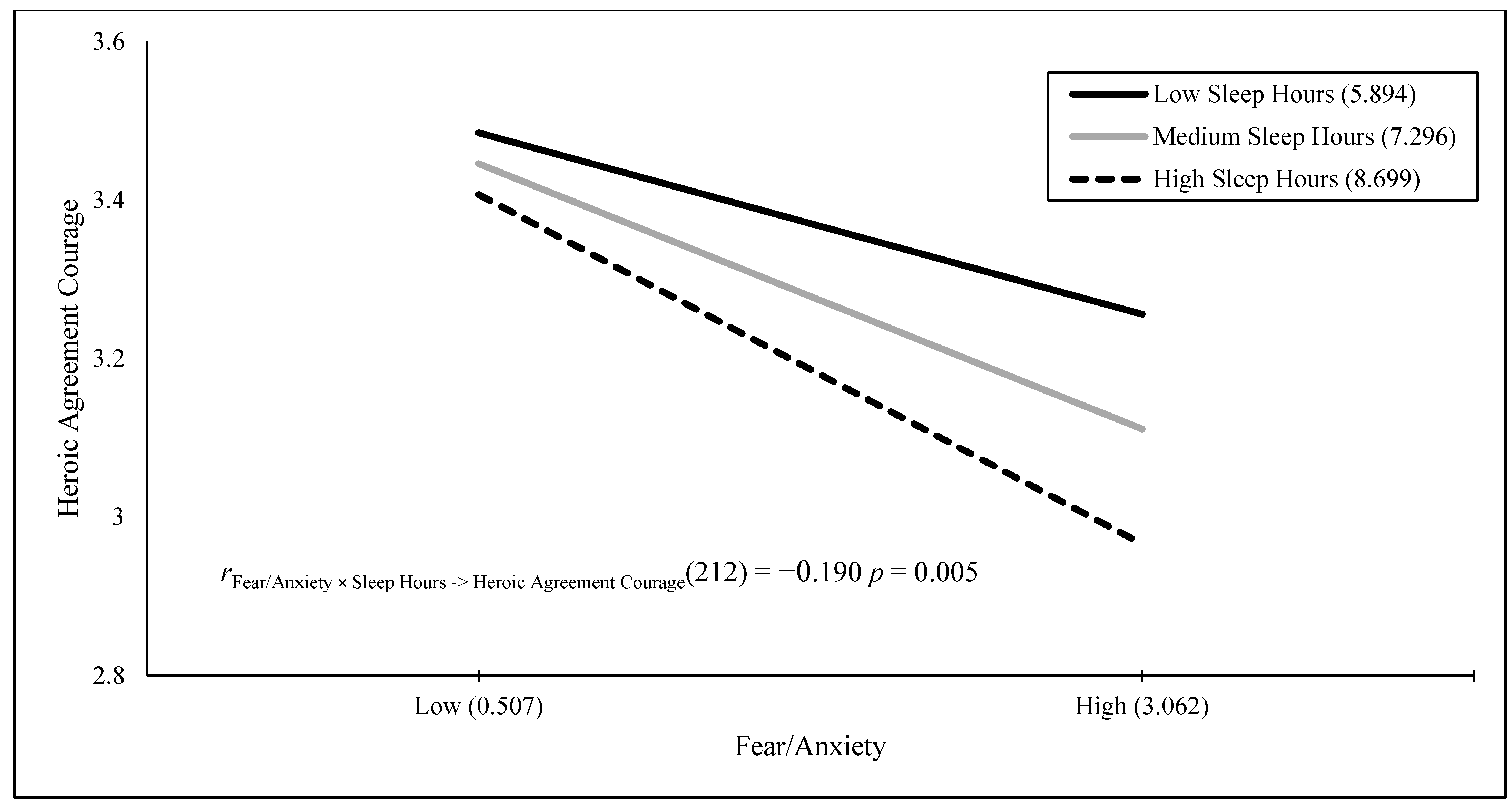

Table 7 present the correlations, and they are listed below. Heroic agreement courage was negatively correlated with hours of sleep,

r(212) = −0.147,

p = 0.032, and the Fear/Anxiety × Hours of Sleep interaction,

r(212) = −0.190,

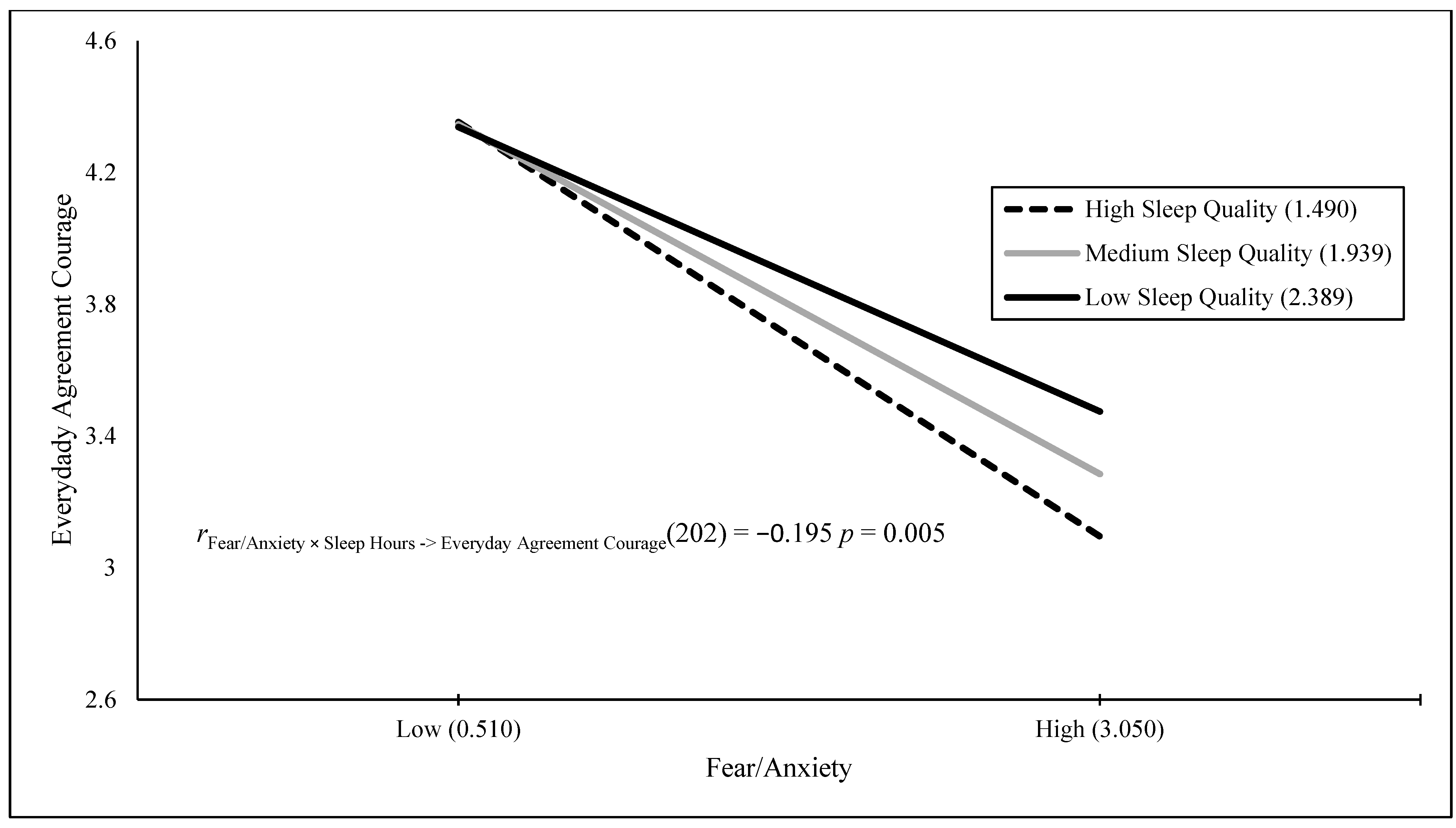

p = 0.005. In addition, everyday agreement courage was negatively correlated with fear/anxiety,

r(210) = −0.236,

p = 0.001, the Fear/Anxiety × Poor Sleep interaction,

r(202) = −0.195,

p = 0.005, and the Fear/Anxiety × Hours of Sleep interaction,

r(210) = −0.249,

p = 0.001. Total (heroic and everyday) agreement courage was negatively correlated with hours of sleep,

r(205) = −0.139,

p < 0.05, fear/anxiety,

r(205) = −0.238,

p = 0.001, the Fear/Anxiety × Poor Sleep interaction,

r(197) = −0.197,

p = 0.005, and the Fear/Anxiety × Hours of Sleep interaction,

r(205) = −0.275,

p < 0.001.

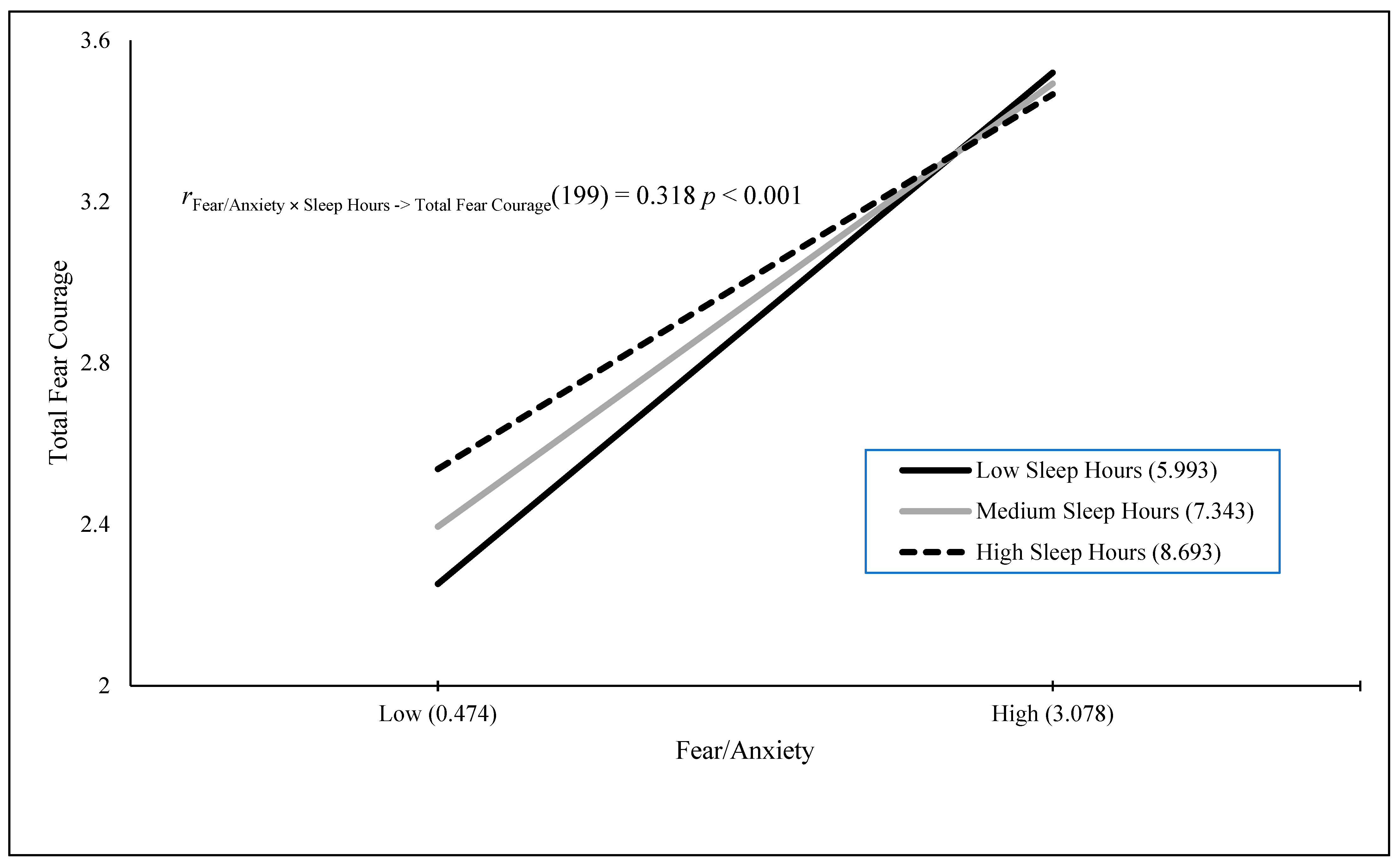

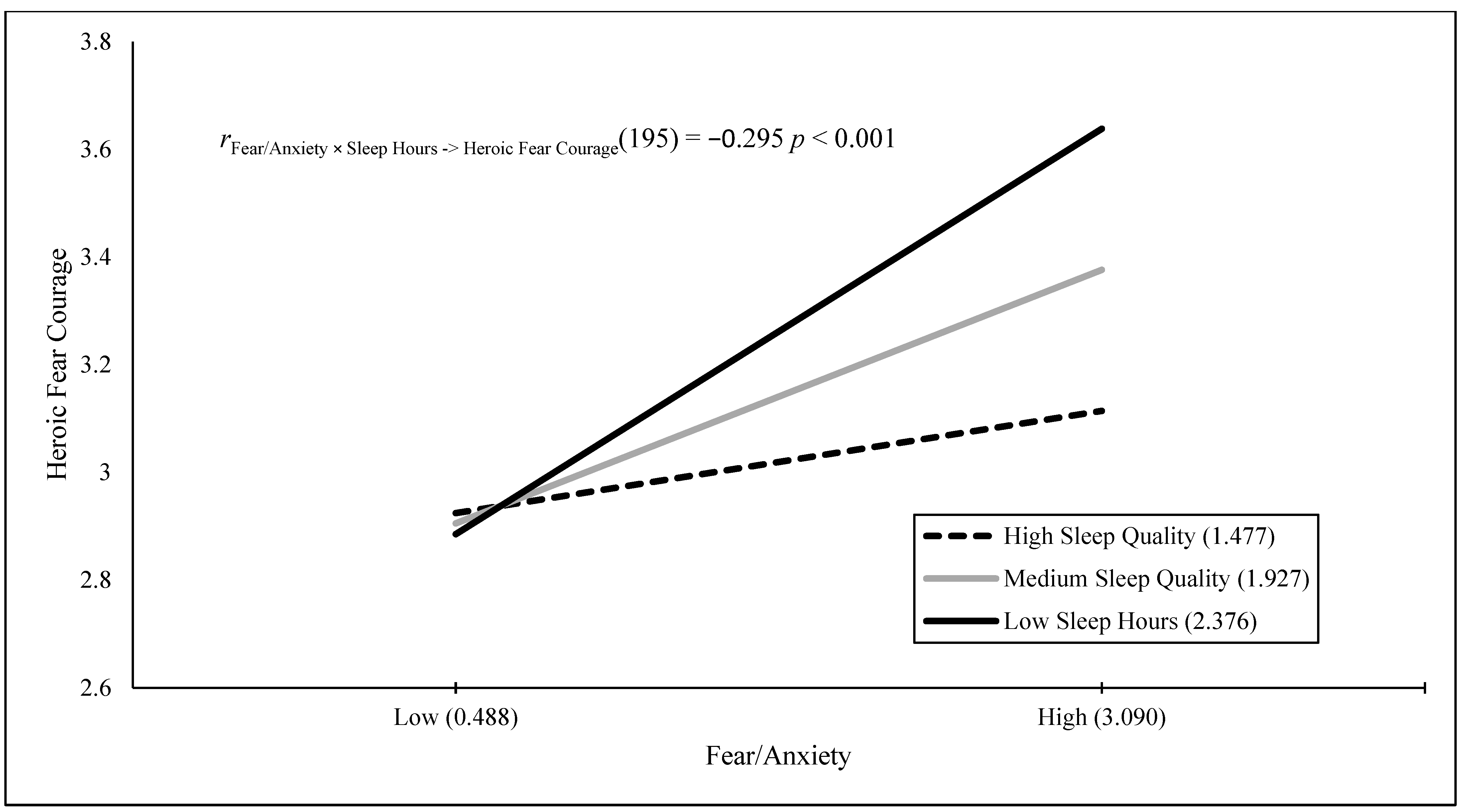

Fear when engaging in heroically courageous actions was positively correlated with poor sleep quality, r(195) = 0.250, p < 0.001, fear/anxiety, r(204) = 0.209, p = 0.003, the Fear/Anxiety × Poor Sleep interaction, r(195) = 0.295, p < 0.001, and the Fear/Anxiety × Hours of Sleep interaction, r(204) = 0.197, p = 0.005. Fear when engaging in daily courageous actions was positively correlated with poor sleep quality, r(198) = 0.295, p < 0.001, fear/anxiety, r(206) = 0.401, p < 0.001, Fear/Anxiety × Poor Sleep interaction, r(198) = 0.414, p < 0.001, and the Fear/Anxiety × Hours of Sleep interaction, r(206) = 0.371, p < 0.001. Fear when engaging in heroically and daily courageous actions was positively correlated with poor sleep quality, r(191) = 0.306, p < 0.001, fear/anxiety, r(199) = 0.345, Fear/Anxiety × Poor Sleep interaction, r(191) = 0.397, p < 0.001, and the Fear/Anxiety × Hours of Sleep interaction, r(199) = 0.318, p < 0.001.

3.2. Regression Analyses of the Courage Measures Accounted for by the Four Predictors

The results of a stepwise regression Model 1 showed that the Fear/Anxiety x Hours of Sleep interaction, B = −0.023 (SE = 0.008), t(203) = −2.822, p = 0.005, negatively predicted 3.8% of the variance in heroic agreement courage. In addition, the results of a stepwise regression Model 2 showed that fear/anxiety, B = −0.663 (SE = 0.187), t(201) = −3.540, p < 0.001 negatively predicted 7.6% of the variance, and the Fear/Anxiety × Poor Sleep interaction, B = 0.126 (SE = 0.062), t(201) = 2.038, p = 0.043, positively predicted an additional 1.9% of the variance for a total of 9.5% of the variance in everyday agreement courage. Furthermore, the results of a stepwise regression Model 1 with the Fear/Anxiety × Hours of Sleep interaction, B = −0.028 (SE = 0.007), t(197) = −4.186, p < 0.001, negatively predicted 8.2% of the variance in total (heroic and daily) agreement courage.

The results of a stepwise regression Model 1 showed that the Fear/Anxiety × Poor Sleep interaction,

B = 0.126 (

SE = 0.029),

t(195) = 4.311,

p < 0.001, positively predicted 8.7% of the variance in fear when engaging in heroically courageous actions. The results of a stepwise regression Model 1 showed that fear/anxiety,

B = 0.565 (

SE = 0.087),

t(198) = 6.506,

p < 0.001, positively predicted 17.6% of the variance in fear when engaging in daily courageous actions. The results of a stepwise regression Model 1 with the Fear/Anxiety × Poor Sleep interaction,

B = 0.157 (

SE = 0.026),

t(191) = 5.972,

p < 0.001, positively predicted 15.7% of the variance in fear when engaging in heroically and daily courageous actions.

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 visually present the results of four significant interactions predicting courage variables. Whereas

Figure 1 displays that sleep is differentially related to courage only at low fear/anxiety levels,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 show that sleep differentially predicts courage only at high levels of fear/anxiety. Although the

Figure 1 results neither support nor refute the prediction that dysfunctional sleep combines with high fear/anxiety and leads to high courage, the results in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 partially support this hypothesis, with the greatest differences in courage due to sleep occurring at high fear/anxiety. Moreover, the results in

Figure 4 fully support the interaction hypothesis.

4. Discussion

The goal of the current study was to examine whether fear/anxiety would combine with sleep measures (amount in hours and poor sleep quality) to predict unique variance in courage measures. Courage was defined as the willingness to be brave despite fear, and it was measured by willingness to engage in heroic, daily, and both types of courageous acts, as well as fear when engaging in heroic, daily, and both types of courageous acts. Fear/anxiety combined with a sleep measure to predict five of the six courage measures. In addition, these interaction variables were the sole predictor in four of the five analyses and the secondary predictor of courage in one analysis. The figures for four of these interactions provide varying degrees of support for the interaction hypothesis, with the first figure neither supporting nor refuting the hypothesis, the second and third figures partially supporting the hypothesis, and the final figure fully supporting the interaction hypothesis. Therefore, the current study was successful in terms of its main goal.

The findings suggest that sleep alone did not significantly predict courage in regression models, including fear/anxiety and the fear/anxiety by sleep interactions, meaning that sleep did not influence courage on its own. While this result seems to contradict past research showing that sleep deprivation was connected to risky/poor decision-making (e.g.,

LoPresti et al., 2016), which is positively related to courage (

Bowers et al., 2022;

Norton & Weiss, 2009), two facts might explain the different results. First, the studies demonstrating a relationship between sleep deprivation and risky decision-making did not examine courage. Second, these studies did not examine sleep along with fear/anxiety and the fear/anxiety by sleep interaction as predictors of risk-taking or courage.

The fact that we did not find a relationship between sleep deprivation and courage in the current study was not surprising because the past literature failed to demonstrate such a relationship. In fact, we had to consult the literature on sleep and risky decision-making (e.g.,

LoPresti et al., 2016) and the literature on risky decision-making and courage (

Chowkase et al., 2024;

Rachman, 2004) to suggest that a link might exist between sleep deprivation and courage. Although we did not find a relationship between sleep deprivation and courage in the literature or the current study, we did find that sleep deprivation and fear/anxiety combined to predict courage. Presumably, poor sleep clouded participants’ cognition (

Csipo et al., 2021;

Lei et al., 2017) and helped them ignore high fear levels and provide courageous responses.

As the ratio of women to men favored women by 2 to 1, this difference could have accounted for the results, because women report higher rates of sleep deprivation than men (

Yaqoot et al., 2016). Although our ratio pales in comparison to nationwide ratios of nearly 4 to 1, with women representing 78% of undergraduate students and 71% of graduate psychology students (

National Science Foundation & National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, 2018 as cited in

Gruber et al., 2021), it could have been an issue. Therefore, future studies should replicate the current study with 250 men and 250 women and determine if the results differ for men and women, such that those results match the results in the current study better for women than men. The population composition may have influenced sleep deprivation, as college students are known for their chronic sleep deprivation. Future research should replicate and extend the current method using non-college students.

As the measure in the current study evaluated hypothetical behaviors, future research could target actual behaviors that demand courage, such as the BAT spider procedure, the BART balloon procedure, and the Iowa Gambling Task. These studies could determine if the results from the current study on imagined actions extend to actual behaviors. Similar findings in these proposed studies to the results in the current study would provide credence for the speculation that sleep deprivation inhibits cognition to override fear and enhance courageous actions. The participants could also be asked if they think their sleepiness helped reduce their fear and increased their courage. Although participant responses could help confirm the cognitive clouding explanation, they cannot refute it because participants may not be aware of the effect even if it is occurring.

The results of this study can be used to help encourage or reduce courageous behaviors. For example, firefighters and police officers must engage in courageous actions, which could be high in newbies and low in journeymen/journeywomen or vice versa. Novice firefighters or police officers may show low levels of courage, and they should increase them. Alternatively, these individuals may show very high levels of courage, which could heighten their anxiety and impair their decision-making, further increasing their courage. Therefore, the goal would be to teach novices to match the willingness to engage in heroic and everyday courage and fear experienced when engaging in these acts of their supervisors and/or experts in the field.

Based on the results of the current study, sleep deprivation and fear/anxiety could be enhanced to increase courage, or they could be decreased to reduce courage. Many fields may already be ahead of this suggestion, as military personnel, police officers (

LoPresti et al., 2016), firefighters, and emergency room doctors (

Bowers et al., 2022) are often sleep deprived, and their jobs demand courage. However, achieving higher courage levels than their supervisors or experts in the field could lead to overconfidence (

Gal & Rucker, 2021) and poor decision-making (

Pury et al., 2024), which could be dangerous for them and the people who count on them to make solid decisions. Therefore, researchers would need to determine the levels of courage experienced by novices and experts in dangerous positions demanding courage using the adapted version of the Woodard-Pury Courage Scale-23 presented in the current study. At that point, courage-increasing or -decreasing programs could be created using relevant fear-provoking situations and techniques that enhance sleep deprivation or sufficient sleep. The individuals could be trained in safe environments rather than learning on the job, which reduces risk for them and the public they serve.

The current study included some limitations. The first limitation of the current study was the sample size. Although we may have found additional effects with a larger sample than the one used in the current study, we found many significant effects that supported the goals and hypotheses in this study. However, future studies could increase the sample size to increase the power and improve the representativeness of the findings. Replication is another way to increase the representativeness and generalization of the results. Similarly, women, as mentioned previously, comprised two-thirds of the sample in the current study; so, future replications could increase the representativeness of the results with large samples containing equal numbers of men and women.

Another limitation was the design of this study, as the current study used a cross-sectional design; these studies can determine correlation, but not causation. Future experiments can manipulate sleep in a sleep lab and fear using movie clips and/or relaxation methods to assess the individual and combined effects of these variables on courage. The randomization of participants to conditions would also control for additional limitations involving habits that increase or reduce stress levels, such as smoking and busy schedules, as well as exercise and meditation, respectively. As shown by

Pury et al. (

2024), political leaning strongly influenced determinations of courage in other individuals, which means that it could have affected the results in the current study. Therefore, future research should measure political leaning and other types of beliefs (e.g., religion) and statistically control their influence on courage.

Some relevant factors could have influenced sleep and fear/anxiety, such as caffeine intake, stress, and comorbid mental health conditions (e.g., depression). Caffeine is a widely used stimulant and can disrupt sleep patterns, especially when consumed before sleeping (

Drake et al., 2013). In addition, caffeine increases anxiety (

Jin et al., 2016). Therefore, caffeine consumption could have influenced these predictors and their individual and combined relations to courage (

Zunhammer et al., 2014). In addition, psychological distress comorbid with anxiety, such as depression, could influence sleep (

Alvaro et al., 2013), complicating the relationship between sleep deprivation and courage. Future studies should control these variables when replicating the current study.

In summary, the goals of the current study were achieved, and the hypotheses were supported. Specifically, poor sleep (in hours and overall sleep quality) combined with fear/anxiety and predicted unique variance for both everyday courage and heroic courage. Although the current study successfully found that fear/anxiety combined with sleep measures to predict various measures of courage, future research should determine the mechanisms behind these findings. Further study on this topic may help researchers understand the optimal levels of courage in different settings, as well as methods to achieve those levels of courage. To potentially apply these findings to real-world settings, future research would first need to extend the procedures in the current study to novices and experts in particular fields (e.g., safety and medicine) and manipulate sleep and fear/anxiety to make novices more like experts. Future research should also control for personal beliefs, such as political leaning. Although the idea of being a fearless superhero seems enticing at first blush, the current study showed that we need fear to overcome, but we also may need a little brain fog from sleep deprivation to jump into threatening situations. Therefore, the conclusion of this work for now is that, as Captain Kirk told Bones in Star Trek: The Final Frontier, fear is needed as it helps us survive, defines us, reveals our limitations and abilities, and it also combines with poor sleep to stay our courage.