Health Behaviors in the Context of Optimism and Self-Efficacy—The Role of Gender Differences: A Cross-Sectional Study in Polish Health Sciences Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

3.2. Setting

3.3. Variables and Instruments

3.4. Study Size

3.5. Statistical Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Psychological Resources and Health Behaviors in the Study Group with Respect to Previous Research Findings

5.2. Dispositional Optimism and Self-Efficacy as Determinants of Health Behaviors

5.3. Gender as a Modifier of the Relationship Between Self-Efficacy, Dispositional Optimism, and the Intensity of Health Behaviors

6. Implications

7. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adorni, R., Zanatta, F., D’Addario, M., Atella, F., Costantino, E., Iaderosa, C., Petarle, G., & Steca, P. (2021). Health-related lifestyle profiles in healthy adults: Associations with sociodemographic indicators, dispositional optimism, and sense of coherence. Nutrients, 13(11), 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowicz, J. (1972). In the search of the definition of health. Studia Filozoficzne, 9, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A., & Wood, R. (1989). Effect of perceived controllability and performance standards on self-regulation of complex decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(5), 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart, M., Szpinda, M., Radzimińska, A., Goch, A., & Zukow, W. (2015). Poczucie własnej skuteczności a zachowania zdrowotne = Self-efficacy and health behawior. Journal of Education, Health and Sport, 5(8), 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyrami, M., Asadi, S., & Hosseini Asl, M. (2015). Prediction of the changes of health behaviors based on the sense of coherence, self-efficacy, optimism and pessimism in students. Journal of Modern Psychological Researches, 9(36), 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bill, V., Wilke, A., Sonsmann, F., & Rocholl, M. (2023). What is the current state of research concerning self-efficacy in exercise behaviour? Protocol for two systematic evidence maps. BMJ Open, 13(8), e070359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, G. D. (1994). Health psychology: Integrating mind and body (pp. 490–498). Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Bjuggren, C. M., & Elert, N. (2019). Gender differences in optimism. Applied Economics, 51(47), 5160–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borek, I., Drzastwa, W., Hanna, M.-Z., Aleksandra, O., & Ewa, B.-R. (2016). Health behaviours and self efficacy of students in maintenance the health. Annales Academiae Medicine Silesianis, 70, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwald, P., & Hobfoll, S. E. (2021). Die Theorie der Ressourcenerhaltung: Implikationen für Stress und Kultur. In T. Ringeisen, P. Genkova, & F. T. L. Leong (Eds.), Handbuch stress und kultur: Interkulturelle und kulturvergleichende perspektiven (pp. 77–89). Springer Fachmedien. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2014). Dispositional optimism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(6), 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celano, C. M., Beale, E. E., Freedman, M. E., Mastromauro, C. A., Feig, E. H., Park, E. R., & Huffman, J. C. (2020). Positive psychological constructs and health behavior adherence in heart failure: A qualitative research study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 22(3), 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodkowski, Z. (2023). Optimism in the opinion of the surveyed students of Rzeszów universities. Forum Pedagogiczne, 13(1), 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholewa, K., Majda, A., & Zalewska-Puchała, J. (2015). Analisys of health behaviors of Pakistanis in Europe. Hygeia Public Health, 50(1), 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins, E. M., Kim, J. K., & Solé-Auró, A. (2011). Gender differences in health: Results from SHARE, ELSA and HRS. European Journal of Public Health, 21(1), 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, W., & Cross, C. (2018). Biostatistics: A foundation for analysis in the health sciences (11th ed.). Wiley. Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Biostatistics%3A+A+Foundation+for+Analysis+in+the+Health+Sciences%2C+11th+Edition-p-9781119496571 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Dawson, C. (2023). Gender differences in optimism, loss aversion and attitudes towards risk. British Journal of Psychology, 114(4), 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionigi, A., Casu, G., & Gremigni, P. (2020). Associations of self-efficacy, optimism, and empathy with psychological health in healthcare volunteers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumit, R., Habre, M., Cattan, R., Abi Kharma, J., & Davis, B. (2022). Health-promoting behaviors and self-efficacy among nursing students in times of uncertainty. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 19(6), 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2018). Special eurobarometer 472: Sport and physical activity. Special eurobarometer 472: Sport and physical activity. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/s2164_88_4_472_eng?locale=en (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- European Commission. (2022). Eurobarometer 525–sport and physical activity [text]. European Commission. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_22_5573 (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Fasano, J., Shao, T., Huang, H., Kessler, A. J., Kolodka, O. P., & Shapiro, C. L. (2020). Optimism and coping: Do they influence health outcomes in women with breast cancer? A systemic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 183(3), 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, I., Jacquet, F., & Leroy, N. (2011). Self-efficacy, goals, and job search behaviors. Career Development International, 16(5), 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesconi, C., Niebauer, J., Haber, P., Moser, O., Weitgasser, R., & Lackinger, C. (2023). [Lifestyle: Physical activity and training as prevention and therapy of type 2 diabetes mellitus (Update 2023)]. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift, 135(Suppl 1), 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, S. M. (2020). Lifestyle (medicine) and healthy aging. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 36(4), 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürtjes, S., Voss, C., Rückert, F., Peschel, S. K. V., Kische, H., Ollmann, T. M., Berwanger, J., & Beesdo-Baum, K. (2023). Self-efficacy, stress, and symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents: An epidemiological cohort study with ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Mood & Anxiety Disorders, 4, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, M. (2016). Sense of generalized self-efficacy versus dietary choices of young women engaged in fitness for recreational purposes. Medycyna Ogólna i Nauki o Zdrowiu, 22(3), 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giltay, E. J., Geleijnse, J. M., Zitman, F. G., Buijsse, B., & Kromhout, D. (2007). Lifestyle and dietary correlates of dispositional optimism in men: The Zutphen Elderly Study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63(5), 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A., & Helmut-König, H. (2017). The role of self-efficacy, self-esteem and optimism for using routine health check-ups in a population-based sample. A longitudinal perspective. Preventive Medicine, 105, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamerman, E. J., Aggarwal, A., & Poupis, L. M. (2023). Generalized self-efficacy and compliance with health behaviours related to COVID-19 in the US. Psychology & Health, 38(8), 969–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, B., Lee, J. B., Marquering, W., & Zhang, C. Y. (2014). Gender differences in optimism and asset allocation. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 107, 630–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Z. (2012). Narzędzia pomiaru w promocji i psychologi zdrowia (Measurement Tools in Health Promotion and Psychology). Pracowania Testów Psychologicznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Pscyhologicznego. [Google Scholar]

- Knapova, L., Cho, Y. W., Chow, S.-M., Kuhnova, J., & Elavsky, S. (2024). From intention to behavior: Within- and between-person moderators of the relationship between intention and physical activity. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 71, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronrod, A., Grinstein, A., & Shuval, K. (2022). Think positive! Emotional response to assertiveness in positive and negative language promoting preventive health behaviors. Psychology & Health, 37(11), 1309–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropornicka, B., Baczewska, B., Dragan, W., Krzyżanowska, E., Olszak, C., & Szymczuk, E. (2015). Zachowania zdrowotne studentów Uniwersytetu Medycznego w Lublinie w zależności od miejsca zamieszkania. Rozprawy Społeczne, 9(2), 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kupcewicz, E., Mikla, M., Kadučáková, H., Schneider-Matyka, D., & Grochans, E. (2022a). Health behaviours and the sense of optimism in nursing students in Poland, Spain and Slovakia during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupcewicz, E., Rachubińska, K., Gaworska-Krzemińska, A., Andruszkiewicz, A., Kuźmicz, I., Kozieł, D., & Grochans, E. (2022b). Health Behaviours among Nursing Students in Poland during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients, 14(13), 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusol, K., & Kaewpawong, P. (2023). Perceived self-efficacy, preventive health behaviors and quality of life among nursing students in Nakhon Si Thammarat Province, Thailand During the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Preference and Adherence, 17, 1989–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladouceur, R. (2019). Prescribing happiness. Canadian Family Physician Medecin De Famille Canadien, 65(9), 599. [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde, M. (1974). A new perspective on the health of Canadiand. Available online: https://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/pdf/perspect-eng.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Lange, D., Barz, M., Baldensperger, L., Lippke, S., Knoll, N., & Schwarzer, R. (2018). Sex differential mediation effects of planning within the health behavior change process. Social Science & Medicine, 211, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łatka, J., Majda, A., & Pyrz, B. (2013). Dispositional optimism and health behavior of patients with hypertensive disease. Nursing Problems/Problemy Pielęgniarstwa, 21(1), 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lesińska-Sawicka, M., Pisarek, E., & Nagórska, M. (2021). The health behaviours of students from selected countries—A comparative study. Nursing Reports, 11(2), 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-C., & Raghubir, P. (2005). Gender differences in unrealistic Optimism about marriage and divorce: Are men more optimistic and women more realistic? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(2), 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizarte Simón, E. J., Gijón Puerta, J., Galván Malagón, M. C., & Khaled Gijón, M. (2024a). Influence of Self-Efficacy, Anxiety and Psychological Well-Being on Academic Engagement During University Education. Education Sciences, 14(12), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarte Simón, E. J., Khaled Gijón, M., Galván Malagón, M. C., & Gijón Puerta, J. (2024b). Challenge-obstacle stressors and cyberloafing among higher vocational education students: The moderating role of smartphone addiction and Maladaptive. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1358634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (1990). A theory of goal setting & task performance (pp. xviii, 413). Prentice-Hall, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, S. R., McMahon, C. J., & Brawley, L. R. (2020). Self-regulatory efficacy for exercise in cardiac rehabilitation: Review and recommendations for measurement. Rehabilitation Psychology, 65(3), 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, A. (2004). Change in breast self-examination behavior: Effects of intervention on enhancing self-efficacy. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 11(2), 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, A., Sobczyk, A., & Abraham, C. (2007). Planning to lose weight: Randomized controlled trial of an implementation intention prompt to enhance weight reduction among overweight and obese women. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 26(4), 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A., Peralta, M., Martins, J., Loureiro, V., Almanzar, P. C., & de Matos, M. G. (2019). Few European adults are living a healthy lifestyle. American Journal of Health Promotion: AJHP, 33(3), 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerstwo Sportu i Turystyki. (2021). Poziom aktywności fizycznej Polaków 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/sport/aktywnosc-fizyczna-spoleczenstwa2 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Mohsin, Z., Shahed, S., & Sohail, T. (2023). Self-efficacy, Optimism and social support as predictors of health behaviors in young adults. Pakistan Social Sciences Review, 7(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, G., Pawlak, K., Duda, S., Kulik, A., & Nowak, D. (2018). Poczucie własnej skuteczności a zachowania zdrowotne i satysfakcja z życia studentów dietetyki. Psychologia Rozwojowa, 23(3), 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poprawa, R. (1996). Zasoby osobiste w radzeniu sobie ze stresem. In G. Dolińska-Zygmunt (Ed.), Elementy psychologii zdrowia (pp. 101–136). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 19(3), 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramar, K., Malhotra, R. K., Carden, K. A., Martin, J. L., Abbasi, F. F., Aurora, R. N., Kapur, V. K., Olson, E. J., Rosen, C. L., Rowley, J. A., Shelgikar, A. V., & Trotti, L. M. (2021). Sleep is essential to health: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 17(10), 2115–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, H. N., Scheier, M. F., & Greenhouse, J. B. (2009). Optimism and physical health: A meta-analytic review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 37(3), 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, K. A., Perez, T., White-Levatich, A., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2022). Gender differences and roles of two science self-efficacy beliefs in predicting post-college outcomes. The Journal of Experimental Education, 90(2), 344–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I. M., Derryberry, M., & Carriger, B. K. (1959). Why people fail to seek poliomyelitis vaccination. Public Health Reports, 74(2), 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovniak, L. S., Anderson, E. S., Winett, R. A., & Stephens, R. S. (2002). Social cognitive determinants of physical activity in young adults: A prospective structural equation analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24(2), 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, I. Z. (2023). Lifestyle medicine as a modality for prevention and management of chronic diseases. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences, 18(5), 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L. (2022). The impact of nutrition and lifestyle modification on health. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 97, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (2018). Dispositional optimism and physical health: A long look back, a quick look forward. American Psychologist, 73(9), 1082–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheier, M. F., Swanson, J. D., Barlow, M. A., Greenhouse, J. B., Wrosch, C., & Tindle, H. A. (2021). Optimism versus pessimism as predictors of physical health: A comprehensive reanalysis of dispositional optimism research. American Psychologist, 76(3), 529–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R. (1992). Self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors: Theoretical approaches and a new model. In Self-efficacy: Thought control of action (pp. 217–243). Hemisphere Publishing Corp. Available online: https://awspntest.apa.org/record/1992-97719-010 (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Schwarzer, R. (2008). Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology, 57(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R. (2016). Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) as a theoretical framework to understand behavior change. Actualidades En Psicología, 30(121), 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R., & Fuchs, R. (1995). Self-Efficacy and Health Behaviours. In Predicting health behaviour: Research and practice with social cognition models. Open University Press. Available online: https://userpage.fu-berlin.de/gesund/publicat/conner9.htm (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Schwarzer, R., Lippke, S., & Luszczynska, A. (2011). Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: The Health Action Process Approach (HAPA). Rehabilitation Psychology, 56(3), 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R., & Łuszczyńska, A. (2022). Self efficacy. In W. Ruch (Ed.), Handbook of positive psychology assessment (pp. 207–214). Hogrefe Publishing GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Sekuła, M., Boniecka, I., & Paśnik, K. (2019). Assessment of health behaviors, nutritional behaviors, and self-efficacy in patients with morbid obesity. Psychiatria Polska, 53(5), 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P., & Webb, T. L. (2016). The intention–behavior gap. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkullaku, R. (2013). The relationship between self—efficacy and academic performance in the context of gender among Albanian students. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Relationship-between-Self-efficacy-and-Academic-Shkullaku/52cfd34214a96aae5ea8ba2e6312620ff1b3ba32 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Sood, R., Jenkins, S. M., Sood, A., & Clark, M. M. (2019). Gender differences in self-perception of health at a wellness center. American Journal of Health Behavior, 43(6), 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stach, R. (2006). Optymizm. Badania nad optymizmem jako mechanizmem adaptacyjnym. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe, A., Wright, C., Kunz-Ebrecht, S. R., & Iliffe, S. (2006). Dispositional optimism and health behaviour in community-dwelling older people: Associations with healthy ageing. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11((Pt 1)), 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrjälä, A.-M. H., Knuuttila, M. L. E., & Syrjälä, L. K. (2001). Self-efficacy perceptions in oral health behavior. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 59(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślusarska, B. (2012). The relationship between dispositional optimism and selected lifestyle indicators of people working in the prevention of cardiovascular risk. Folia Cardiologica, 7(1), 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Ślusarska, B., Nowicki, G., & Piasecka, H. (2012). Health behaviors in the prevention of cardiovascular risk. Polish Journal of Cardiology, 14(4), 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A. E., Anisimowicz, Y., Miedema, B., Hogg, W., Wodchis, W. P., & Aubrey-Bassler, K. (2016). The influence of gender and other patient characteristics on health care-seeking behaviour: A QUALICOPC study. BMC Family Practice, 17(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel-Fitzgerald, C., James, P., Kim, E. S., Zevon, E. S., Grodstein, F., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2019). Prospective associations of happiness and optimism with lifestyle over up to two decades. Preventive Medicine, 126, 105754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldrop, D., Lightsey, O. R., Jr., Ethington, C. A., Woemmel, C. A., & Coke, A. L. (2001). Self-efficacy, optimism, health competence, and recovery from orthopedic surgery. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48(2), 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, L. M., & Schwarzer, R. (2025). Self-efficacy and health. In P. Liamputtong (Ed.), Handbook of concepts in health, health behavior and environmental health (pp. 1–26). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2004). Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9241592222 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- World Health Organization & Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2023). Step up! Tackling the burden of insufficient physical activity in Europeen. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/publications/step-up-tackling-the-burden-of-insufficient-physical-activity-in-europe-500a9601-en.htm (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Zadworna, M., & Ogińska-Bulik, N. (2013). Zachowania zdrowotne osób w wieku senioralnym—rola optymizmu (Health behaviors in the group of people in late adulthood period—the role of optimism). Psychogeriatria Polska, 10, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G., Feng, W., Zhao, L., Zhao, X., & Li, T. (2024). The association between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management and mental health among adolescents. Scientific Reports, 14, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

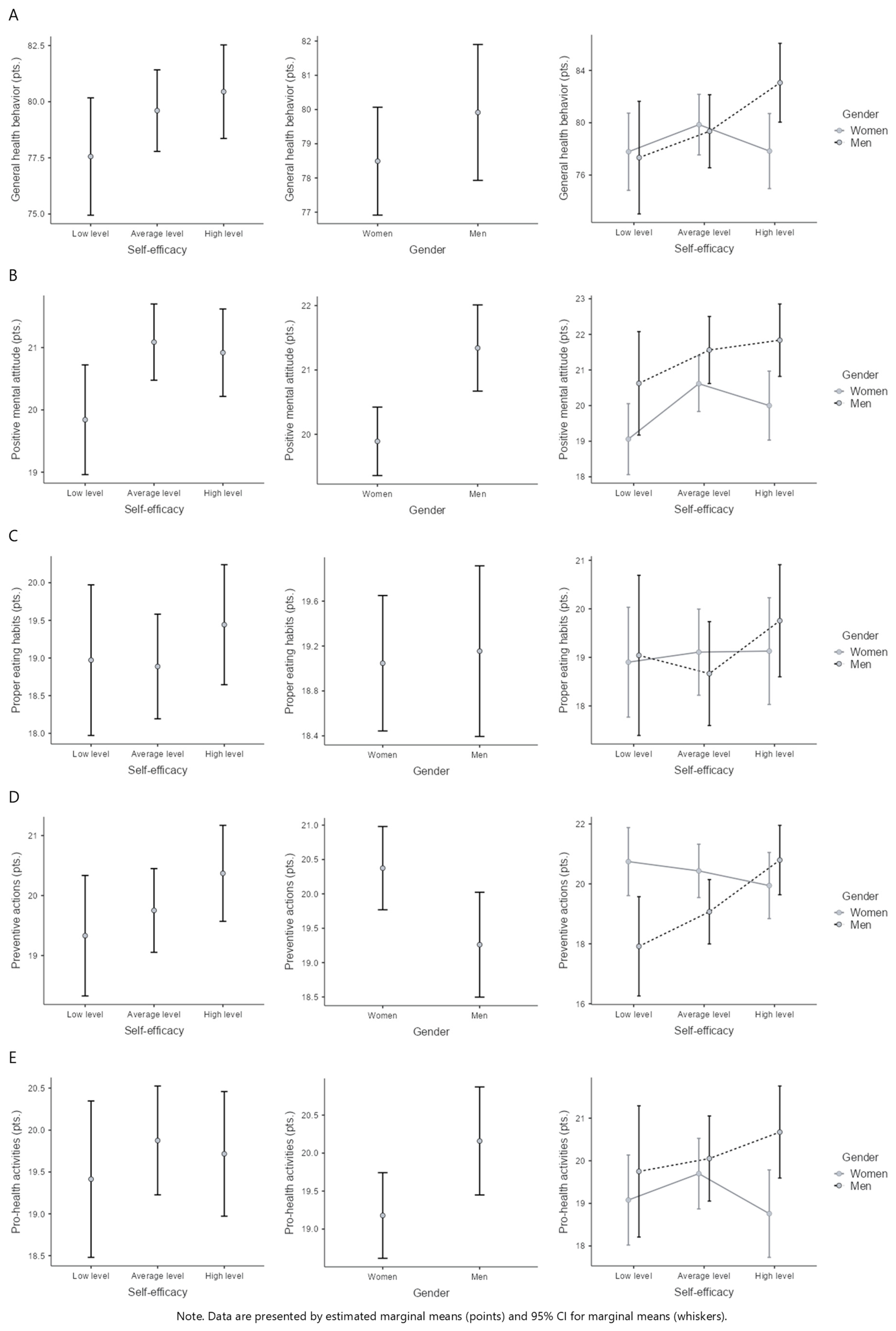

| Health Behaviors | Self-Efficacy | Gender | M ± SD | Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Health Behaviors (pts.) | Low level | Women | 77.8 ± 11.4 | Self-efficacy | F(2, 312) = 1.47, p = 0.231, η2p = 0.01 |

| Average level | 79.9 ± 12.1 | Gender | F(1, 312) = 1.22, p = 0.270, η2p < 0.01 | ||

| High level | 77.8 ± 10.5 | Self-efficacy*Gender | F(2, 312) = 2.41, p = 0.091, η2p = 0.02 | ||

| Low level | Men | 77.3 ± 9.2 | |||

| Average level | 79.4 ± 10.3 | ||||

| High level | 83.1 ± 8.8 | ||||

| Positive Mental Attitude (pts.) | Low level | Women | 19.1 ± 4.3 | Self-efficacy | F(2, 312) = 2.76, p = 0.065, η2p = 0.02 |

| Average level | 20.6 ± 3.8 | Gender | F(1, 312) = 11.15, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.03 | ||

| High level | 20.0± 3.2 | Self-efficacy*Gender | F(2, 312) = 0.47, p = 0.626, η2p < 0.01 | ||

| Low level | Men | 20.6 ± 2.8 | |||

| Average level | 21.6 ± 3.8 | ||||

| High level | 21.8 ± 3.1 | ||||

| Proper Eating Habits (pts.) | Low level | Women | 18.9 ± 3.9 | Self-efficacy | F(2, 312) = 0.57, p = 0.566, η2p < 0.01 |

| Average level | 19.1 ± 4.7 | Gender | F(1, 312) = 0.05, p = 0.827, η2p < 0.01 | ||

| High level | 19.1 ± 4.3 | Self-efficacy*Gender | F(2, 312) = 0.50, p = 0.608, η2p < 0.01 | ||

| Low level | Men | 19.0 ± 2.9 | |||

| Average level | 18.7 ± 4.2 | ||||

| High level | 19.8 ± 3.4 | ||||

| Preventive Actions (pts.) | Low level | Women | 20.7 ± 4.0 | Self-efficacy | F(2, 312) = 1.37, p = 0.256, η2p = 0.01 |

| Average level | 20.4 ± 4.5 | Gender | F(1, 312) = 5.06, p = 0.025, η2p = 0.02 | ||

| High level | 19.9 ± 3.9 | Self-efficacy*Gender | F(2, 312) = 4.32, p = 0.014, η2p = 0.03 | ||

| Low level | Men | 17.9 ± 3.1 | |||

| Average level | 19.1 ± 4.4 | ||||

| High level | 20.8 ± 3.9 | ||||

| Pro-health Activities (pts.) | Low level | Women | 19.1 ± 4.2 | Self-efficacy | F(2, 312) = 0.32, p = 0.727, η2p < 0.01 |

| Average level | 19.7 ± 3.6 | Gender | F(1, 312) = 4.52, p = 0.034, η2p = 0.01 | ||

| High level | 18.8 ± 3.8 | Self-efficacy*Gender | F(2, 312) = 1.21, p = 0.284, η2p = 0.01 | ||

| Low level | Men | 19.8 ± 3.9 | |||

| Average level | 20.1 ± 4.0 | ||||

| High level | 20.7 ± 3.5 | ||||

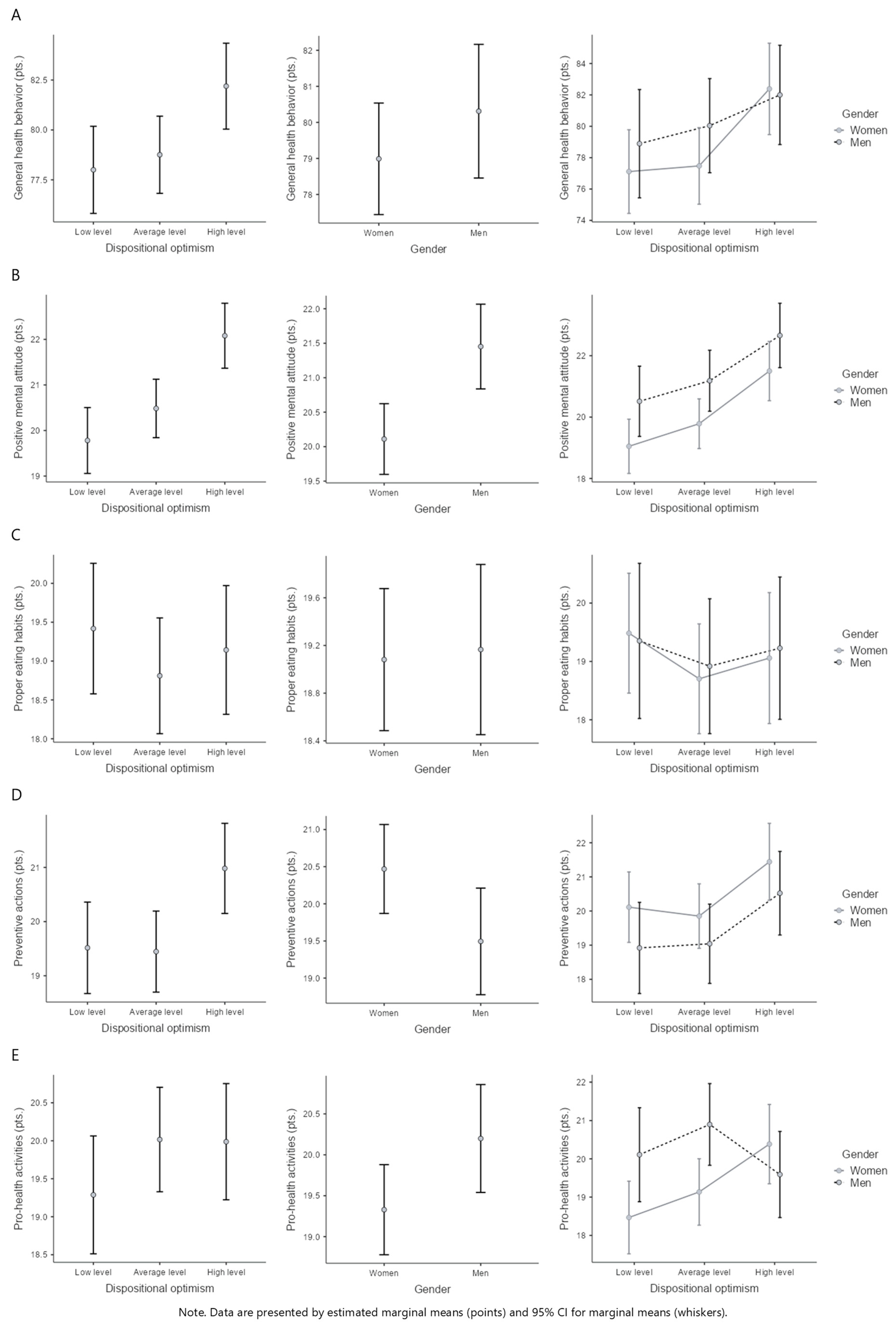

| Health Behaviors | Dispositional Optimism | Gender | M ± SD | Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Health Behaviors (pts.) | Low level | Women | 77.1 ± 11.2 | Dispositional optimism | F(2, 312) = 4.22, p = 0.016, η2p = 0.03 |

| Average level | 77.5 ± 11.8 | Gender | F(1, 312) = 1.16, p = 0.283, η2p < 0.01 | ||

| High level | 82.4 ± 10.5 | Dispositional optimism*Gender | F(2, 312) = 0.52, p = 0.593, η2p < 0.01 | ||

| Low level | Men | 78.9 ± 9.8 | |||

| Average level | 80.0 ± 9.9 | ||||

| High level | 82.0 ± 9.4 | ||||

| Positive Mental Attitude (pts.) | Low level | Women | 19.0 ± 3.6 | Dispositional optimism | F(2, 312) = 10.54, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.06 |

| Average level | 19.8 ± 4.0 | Gender | F(1, 312) = 10.87, p = 0.001, η2p = 0.03 | ||

| High level | 21.5 ± 3.4 | Dispositional optimism*Gender | F(2, 312) = 0.05, p = 0.951, η2p < 0.01 | ||

| Low level | Men | 20.5 ± 4.0 | |||

| Average level | 21.2 ± 3.0 | ||||

| High level | 22.7 ± 2.9 | ||||

| Proper Eating Habits (pts.) | Low level | Women | 19.5 ± 4.0 | Dispositional optimism | F(2, 312) = 0.57, p = 0.564, η2p < 0.01 |

| Average level | 18.7 ± 4.5 | Gender | F(1, 312) = 0.03, p = 0.859, η2p < 0.01 | ||

| High level | 19.1 ± 4.5 | Dispositional optimism*Gender | F(2, 312) = 0.05, p = 0.949, η2p < 0.01 | ||

| Low level | Men | 19.4 ± 3.3 | |||

| Average level | 18.9 ± 4.4 | ||||

| High level | 19.2 ± 3.1 | ||||

| Preventive Actions (pts.) | Low level | Women | 20.1 ± 4.3 | Dispositional optimism | F(2, 312) = 4.37, p = 0.013, η2p = 0.03 |

| Average level | 19.9 ± 4.1 | Gender | F(1, 312) = 4.21, p = 0.041, η2p = 0.01 | ||

| High level | 21.4 ± 4.1 | Dispositional optimism*Gender | F(2, 312) = 0.06, p = 0.944, η2p < 0.01 | ||

| Low level | Men | 18.9 ± 3.9 | |||

| Average level | 19.0 ± 4.2 | ||||

| High level | 20.5 ± 4.1 | ||||

| Pro-health Activities (pts.) | Low level | Women | 18.5 ± 4.1 | Dispositional optimism | F(2, 312) = 1.15, p = 0.318, η2p = 0.01 |

| Average level | 19.1 ± 3.9 | Gender | F(1, 312) = 3.97, p = 0.047, η2p = 0.01 | ||

| High level | 20.4 ± 3.2 | Dispositional optimism*Gender | F(2, 312) = 3.57, p = 0.029, η2p = 0.02 | ||

| Low level | Men | 20.1 ± 3.8 | |||

| Average level | 20.9 ± 3.1 | ||||

| High level | 19.6 ± 4.5 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dębska-Janus, M.; Rozpara, M.; Muchacka-Cymerman, A.; Dębski, P.; Tomik, R. Health Behaviors in the Context of Optimism and Self-Efficacy—The Role of Gender Differences: A Cross-Sectional Study in Polish Health Sciences Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050626

Dębska-Janus M, Rozpara M, Muchacka-Cymerman A, Dębski P, Tomik R. Health Behaviors in the Context of Optimism and Self-Efficacy—The Role of Gender Differences: A Cross-Sectional Study in Polish Health Sciences Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(5):626. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050626

Chicago/Turabian StyleDębska-Janus, Małgorzata, Michał Rozpara, Agnieszka Muchacka-Cymerman, Paweł Dębski, and Rajmund Tomik. 2025. "Health Behaviors in the Context of Optimism and Self-Efficacy—The Role of Gender Differences: A Cross-Sectional Study in Polish Health Sciences Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 5: 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050626

APA StyleDębska-Janus, M., Rozpara, M., Muchacka-Cymerman, A., Dębski, P., & Tomik, R. (2025). Health Behaviors in the Context of Optimism and Self-Efficacy—The Role of Gender Differences: A Cross-Sectional Study in Polish Health Sciences Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 626. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050626