The Contribution of Negative Expectancies to Emotional Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Importance of Emotional Resilience

1.2. Anxiety Reactivity and Perseveration as Manifestations of Emotional Resilience

1.3. Negative Expectancy Bias and Anxiety Reactivity

1.4. Negative Expectancy Bias and Anxiety Perseveration

1.5. Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Film Montage

2.3. Questionnaires

2.3.1. Negative Expectancy Bias Assessment

2.3.2. Negative Experience Index Assessment

2.3.3. Assessment of Anxiety Reactivity and Perseveration

2.3.4. Information Statements Describing Film Montage

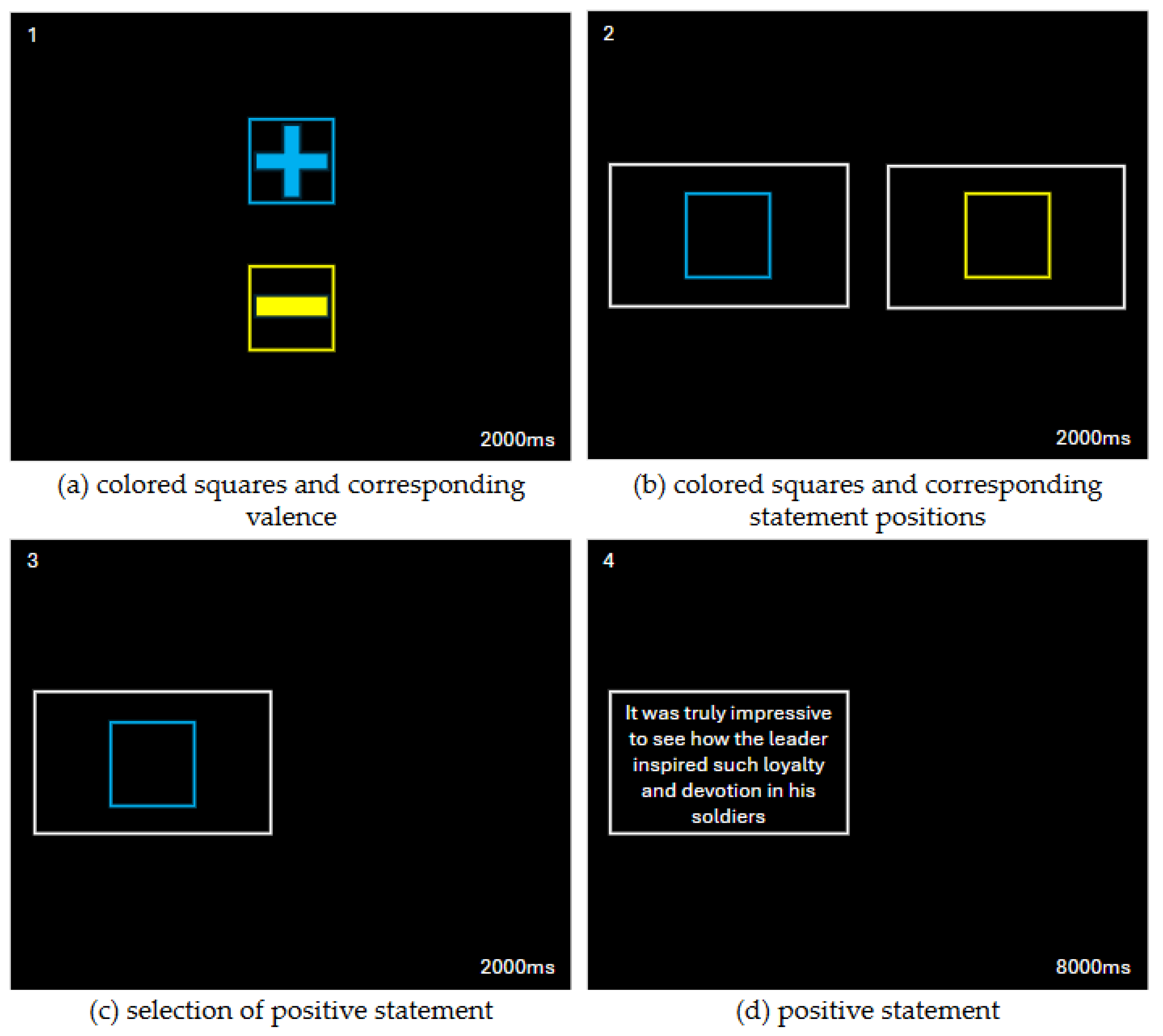

2.4. Information Statement Presentation and Selective Interrogation Bias Assessment

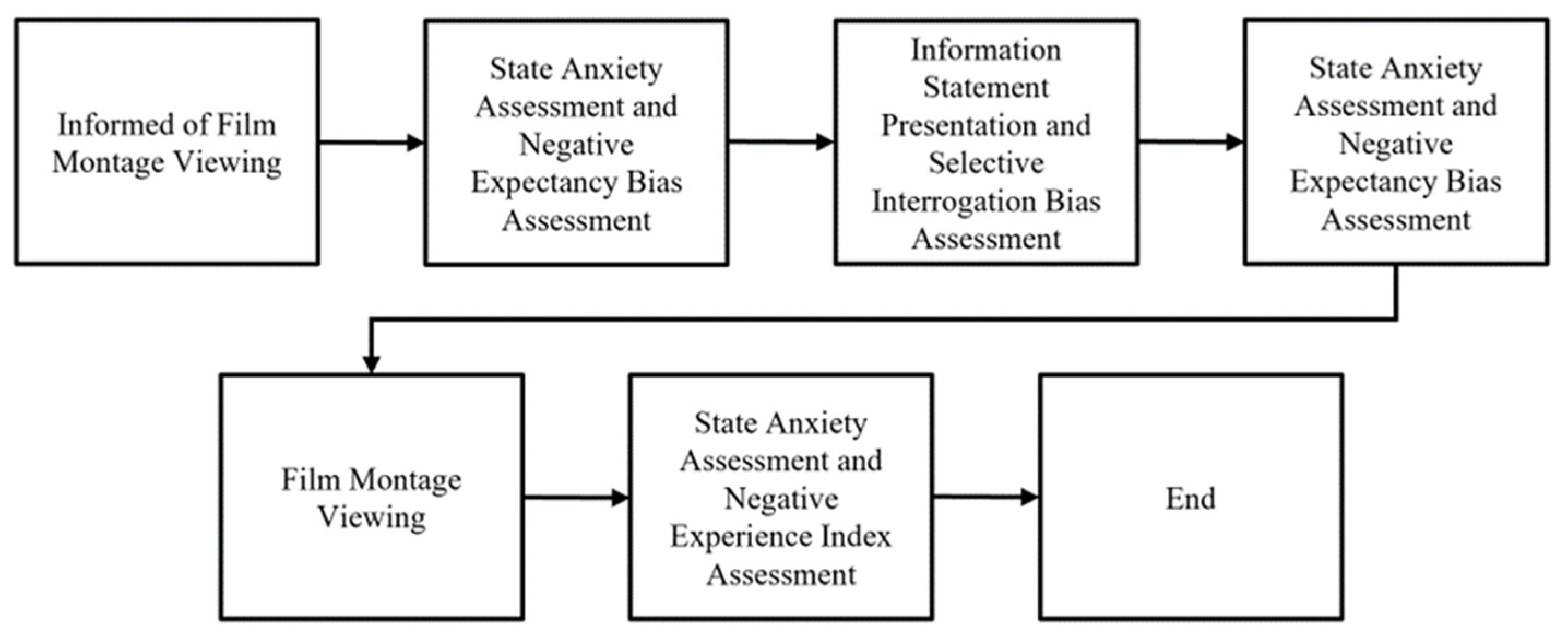

2.5. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Data Cleaning, Preparation, and Analysis

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

3.3. Is There an Association Between Negative Expectancy Bias and Anxiety Reactivity?

3.3.1. Effect Concerning Association Between Negative Selective Interrogation Bias and Anxiety Reactivity

3.3.2. Effect Concerning Association Between Negative Expectancy Bias Elevation and Anxiety Reactivity

3.3.3. Effect Concerning Association Between Negative Selective Interrogation Bias and Negative Expectancy Bias Elevation

3.3.4. Effect Concerning Mediation of Association Between Negative Selective Interrogation Bias and Anxiety Reactivity by Negative Expectancy Bias Elevation

3.4. Is There an Association Between Negative Expectancy Bias and Anxiety Perseveration?

3.4.1. Did Negative Expectancy Bias Predict Anxiety Perseveration?

3.4.2. Does Negative Expectancy Bias Predict Anxiety Perseveration Directly or Through the Mediating Influence of Negative Experience Index?

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Theoretical and Clinical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Negative Experience Index Assessment (Items)

References

- Alfons, A., fer Yasin Ates, N., F Groenen, P. J., & Yasin Ates, N. (2022). A robust bootstrap test for mediation analysis. Sage Journals, 25(3), 591–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, A. M., Elfaki, A., Wahab, M. M. A., Aljehani, Y., Alkhunaizi, A. A., Othman, S. A., & Alshamlan, R. A. (2023). Psychological resilience, anxiety, and well-being of health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 16, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aue, T., & Okon-Singer, H. (2015). Expectancy biases in fear and anxiety and their link to biases in attention. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A. T. (1970). Cognitive therapy: Nature and relation to behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 1(2), 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J., & Kremen, A. M. (1996). IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouter, L. M., & Riet, G. T. (2020). Replication research series-paper 2: Empirical research must be replicated before its findings can be trusted. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 129, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, G., & Mathews, A. (1987). Anticipatory anxiety and risk perception. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11(5), 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. P., Miles, J. N. V., & Field, Z. C. (2012). Discovering statistics using R (Vol. 62, pp. 1–992). SAGE Publications Ltd. Available online: https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/discovering-statistics-using-r/book236067 (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Grillon, C., Ameli, R., Merikangas, K., Woods, S. W., & Davis, M. (1993). Measuring the time course of anticipatory anxiety using the fear-potentiated startle reflex. Psychophysiology, 30(4), 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gromer, D., Hildebrandt, L. K., & Stegmann, Y. (2023). The role of expectancy violation in extinction learning: A two-day online fear conditioning study. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 5(2), e9627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konradt, C. E., Cardoso, T. d. A., Mondin, T. C., Souza, L. D. d. M., Kapczinski, F., da Silva, R. A., & Jansen, K. (2018). Impact of resilience on the improvement of depressive symptoms after cognitive therapies for depression in a sample of young adults. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 40(3), 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1993). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Available online: https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=i-ySQQuUpr8C&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&ots=DhFQqrjkU9&sig=KtZpyyiih9cPE8DV6mtNe4hsXQc&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Liu, Y., Pan, H., Yang, R., Wang, X., Rao, J., Zhang, X., & Pan, C. (2021). The relationship between test anxiety and emotion regulation: The mediating effect of psychological resilience. Annals of General Psychiatry, 20(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, P. J., Chrabaszcz, J. S., Peterson, R. A., Rohrbeck, C. A., Roemer, E. C., & Mercurio, A. E. (2014). Psychological resilience: The impact of affectivity and coping on state anxiety and positive emotions during and after the Washington, DC sniper killings. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 27(2), 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A., MacLeod, C., & Grafton, B. (2024). The role of expectancies and selective interrogation of information in trait anxiety-linked affect when approaching potentially stressful future events. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 179, 104568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rief, W., Sperl, M. F. J., Braun-Koch, K., Khosrowtaj, Z., Kirchner, L., Schäfer, L., Schwarting, R. K. W., Teige-Mocigemba, S., & Panitz, C. (2022). Using expectation violation models to improve the outcome of psychological treatments. Clinical Psychology Review, 98, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S. J., Sünram-Lea, S. I., Leach, J., & Owen-Lynch, P. J. (2008). The effects of exposure to an acute naturalistic stressor on working memory, state anxiety and salivary cortisol concentrations. Stress, 11(2), 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudaizky, D., Page, A. C., & MacLeod, C. (2012). Anxiety reactivity and anxiety perseveration represent dissociable dimensions of trait anxiety. Emotion, 12(5), 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto. [Google Scholar]

- Steinman, S. A., Smyth, F. L., Bucks, R. S., MacLeod, C., & Teachman, B. A. (2013). Anxiety-linked expectancy bias across the adult lifespan. Cognition & Emotion, 27(2), 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. (2024). Jamovi (Version 2.5) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Tough, J., Grafton, B., MacLeod, C., & van Bockstaele, B. (2024). The contributions of attentional bias and expectancy bias to fluctuations in state anxiety. Cognitive Research and Therapy, 49, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tough, J., Grafton, B., MacLeod, C., & van Bockstaele, B. (2025). Role of information seeking in anxiety-linked expectancies. Open Science Framework. Preprint. Available online: https://osf.io/s2cpk/files/osfstorage?view_only=7b386cd30de840f78e6aacb4e7d0e094 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

| Mean | Median | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Reactivity | 44.4 | 27 | 96.2 | −161 | 292 |

| Anxiety Perseveration | 331 | 330 | 132 | 45 | 587 |

| Negative Expectancy Bias Elevation | 18.9 | 8 | 79.3 | −197 | 209 |

| Negative Experience Index | 93.3 | 92 | 134 | −251 | 396 |

| Negative Selective Interrogation Bias | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tough, J.; Grafton, B.; MacLeod, C.; Van Bockstaele, B. The Contribution of Negative Expectancies to Emotional Resilience. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040531

Tough J, Grafton B, MacLeod C, Van Bockstaele B. The Contribution of Negative Expectancies to Emotional Resilience. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040531

Chicago/Turabian StyleTough, James, Ben Grafton, Colin MacLeod, and Bram Van Bockstaele. 2025. "The Contribution of Negative Expectancies to Emotional Resilience" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040531

APA StyleTough, J., Grafton, B., MacLeod, C., & Van Bockstaele, B. (2025). The Contribution of Negative Expectancies to Emotional Resilience. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040531