How Do Career Expectations Affect the Social Withdrawal Behavior of Graduates Not in Employment, Education, or Training (NEETs)? The Chain Mediating Role of Human Capital and Problem-Solving Ability

Abstract

1. Introduction

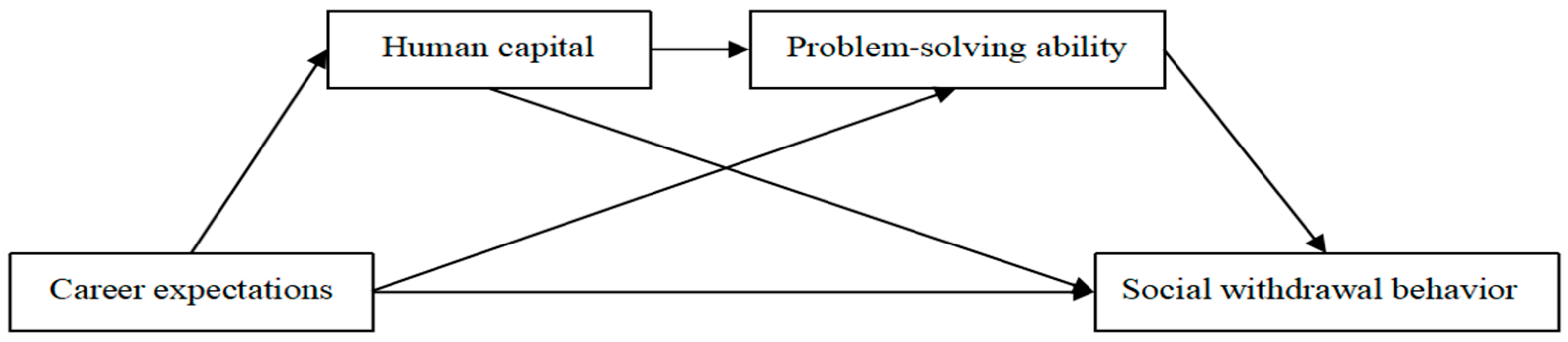

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Career Expectations and Social Withdrawal Behavior

2.2. The Mediating Role of Human Capital

2.3. The Mediating Role of Problem-Solving Ability

2.4. Sequential Mediating Role of Human Capital and Problem-Solving Ability

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Career Expectations

3.2.2. Social Withdrawal Behavior

3.2.3. Human Capital

3.2.4. Problem-Solving Ability

3.2.5. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Common Method Bias Test

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Research Contributions

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afyonoglu, M. F., Yigit, R. R., Misirli, G. N., & Bilgin, O. (2024). Social work graduates as youth not in education, employment, or training (neet) in Türkiye: An intersectional analysis. Journal of Social Service Research, 50(3), 494–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aina, C., Brunetti, I., Mussida, C., & Scicchitano, S. (2024). Even more discouraged? The neet generation at the age of COVID-19. Applied Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, B., & Guneri, O. Y. (2023). Thriving in the face of youth unemployment: The role of personal and social resources. Journal of Employment Counseling, 60(3), 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broschinski, S., Feldhaus, M., Assmann, M.-L., & Heidenreich, M. (2022). The Role of family social capital in school-to-work transitions of young adults in Germany. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 139, 103790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, V. A., Sousa, V., & Marchante, M. (2015). Development and validation of the social and emotional competencies evaluation questionnaire. Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 5(1), 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-Determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Zurilla, T. J., Maydeu-Olivares, A., & Gallardo-Pujol, D. (2011). Predicting social problem solving using personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(2), 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erozkan, A. (2014). Analysis of social problem solving and social self-efficacy in prospective teachers. Kuram Ve Uygulamada Egitim Bilimleri, 14(2), 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. (2012). Neets—Young people not in employment, education or training: Characteristics, costs and policy responses in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. (2016). Exploring the diversity of neets. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, S., & Moldogaziev, T. (2015). Employee empowerment and job satisfaction in the us federal bureaucracy: A self-determination theory perspective. American Review of Public Administration, 45(4), 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauenknecht, M., & Black, D. R. (1995). Social problem-solving inventory for adolescents (Spsi-a): Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 64(3), 522–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, A. (2006). Not a very neet solution: Representing problematic labour market transitions among early school-leavers. Work Employment and Society, 20(3), 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, A. H., & de Jong, P. W. (2021). Costly children: The Motivations for parental investment in children in a low fertility context. Genus, 77(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, R. I., & Paul, B. (2024). Unravelling the interplay between competencies, career preparedness, and perceived employability among postgraduate students: A structural model analysis. Asia Pacific Education Review, 25(2), 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, W., & Van den Brink, H. M. (2000). Education, training and employability. Applied Economics, 32(5), 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grund, J., & Brock, A. (2019). Why we should empty pandora’s box to create a sustainable future: Hope, sustainability and its implications for education. Sustainability, 11(3), 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. C., Boudreaux, M., & Oglesby, M. (2024). Can harman’s single-factor test reliably distinguish between research designs? Not in published management studies. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 33(6), 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y., Hou, Z. J., Zhang, H., & Xiao, Y. T. (2022). Future time perspective, career adaptability, anxiety, and career decision-making difficulty: Exploring mediations and moderations. Journal of Career Development, 49(2), 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A. L. (2020). Labor market uncertainties and youth labor force experiences: Lessons learned. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 688(1), 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F., Liu, D., Gao, P., Shao, H., & Shen, S. (2024). Analysing how government-provided vocational skills training affects migrant workers’ income: A study based on the livelihood capital theory. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. M. H., & Wong, P. W. C. (2015). Youth social withdrawal behavior (hikikomori): A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(7), 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y., & Cho, S. (2011). Predicting creative problem-solving in math from a dynamic system model of creative problem solving ability. Creativity Research Journal, 23(3), 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainert, J., Niepel, C., Murphy, K. R., & Greiff, S. (2019). The incremental contribution of complex problem-solving skills to the prediction of job level, job complexity, and salary. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(6), 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, A. J., Fouad, N., & Ihle-Helledy, K. (2009). Career aspirations and expectations of college students demographic and labor market comparisons. Journal of Career Assessment, 17(2), 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. n.d. Unemployment rate among youth aged 16–24. national data. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=A01 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Oettingen, G., Mayer, D., Thorpe, J. S., Janetzke, H., & Lorenz, S. (2005). Turning fantasies about positive and negative futures into self-improvement goals. Motivation and Emotion, 29(4), 237–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozyilmaz, A. (2020). Hope and human capital enhance job engagement to improve workplace outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93(1), 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, T., Bian, J., & Chen, J. (2024). The status quo, causes, and countermeasures of employment difficulties faced by college graduates in China. Labor History, 65(4), 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S., Morton, M., & Bhattacharya, S. (2018). Hidden human capital: Self-efficacy, aspirations and achievements of adolescent and young women in India. World Development, 111, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K. H., Coplan, R. J., & Bowker, J. C. (2009). Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharabati, A.-A. A., Jawad, S. N., & Bontis, N. (2010). Intellectual capital and business performance in the pharmaceutical sector of jordan. Management Decision, 48(1–2), 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiyuan, Y., Jinxiu, Y., Jingfei, X., Yuling, Z., Longhua, Y., Houjian, L., Wei, L., Hao, C., Guorong, H., & Juan, C. (2022). Impact of human capital and social capital on employability of chinese college students under COVID-19 epidemic-joint moderating effects of perception reduction of employment opportunities and future career clarity. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1046952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegfried, C., Kogler, K., Rausch, A., Seifried, J., Wuttke, E., & Eigenmann, R. (2019). Individual and contextual predictors of domain-specific problem-solving competence in vocational education and training. Zeitschrift Fur Erziehungswissenschaft, 22(4), 989–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A., & Parker, S. K. (2012). Future work selves: How salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 580–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrazas-Bañales, F. (2019). Motivation of music students: School of arts flute orchestra. Praxis & Saber, 10(22), 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy Thi Hai, H., Van Hong, L., Duong Tuan, N., Chi Thi Phuong, N., & Ha Thi Thu, N. (2023). Effects of career development learning on students’ perceived employability: A longitudinal study. Higher Education, 86(2), 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veestraeten, M., Johnson, S. K., Leroy, H., Sy, T., & Sels, L. (2021). Exploring the bounds of pygmalion effects: Congruence of implicit followership theories drives and binds leader performance expectations and follower work engagement. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 28(2), 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Huang, Y., & Xiao, Y. (2021). The mediating effect of social problem-solving between perfectionism and subjective well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 764976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Wang, M., Georgiev, G. V., & Parola, A. (2023). The influence of personal evaluation and social support on career expectations of college students. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Wang, R., & Gu, M. (2022). The group portrait and transformation logic of neet college students. Higher Education Exploration, (4), 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Widyowati, A., Hood, M., Duffy, A., & Creed, P. (2024). The interactive effects of self- and parent-referenced career goal discrepancies on young adults’ career indecision. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., & Li, B. (2001). University graduates’ occupation expectation and its relevant factors. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 7(3), 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M., Lin, H., Lin, Y., & Chang, W. (2013). A study on the tacit knowledge of university faculty: A case study in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Education Review, 14(2), 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, W.-J. J., & Rauscher, E. (2014). Youth early employment and behavior problems: Human capital and social network pathways to adulthood. Sociological Perspectives, 57(3), 382–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yizengaw, J. Y. (2018). Skills gaps and mismatches: Private sector expectations of engineering graduates in Ethiopia. Ids Bulletin-Institute of Development Studies, 49(5), 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F., & Woodman, R. W. (2010). Innovative behavior in the workplace: The role of performance and image outcome expectations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(2), 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Li, Y., Yu, A., & Zhang, W. (2024). Behavioral Characteristics of China’s neet-prone university students and graduates: A survey from southwest China. Behavioral Sciences, 14(2), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P. (2024). 2024 College student employment competitiveness survey report. Available online: https://file.digitaling.com/eImg/uimages/20240711/1720666811119410.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Zheng, D. (2019). Thesis on social withdrawal. Journal of Renmin University of China, 33(6), 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, R. D., Boswell, W. R., Shipp, A. J., Dunford, B. B., & Boudreau, J. W. (2012). Explaining the pathways between approach-avoidance personality traits and employees’ job search behavior. Journal of Management, 38(5), 1450–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zudina, A. (2022). What makes youth become neet? Evidence from Russia. Journal of Youth Studies, 25(5), 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Characteristics | Specific Description | Quantity | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 99 | 43.8% |

| Female | 127 | 56.2% | |

| Age | 18–22 | 171 | 75.7% |

| 22–25 | 45 | 19.9% | |

| 25–29 | 10 | 4.4% | |

| Education | Vocational college | 114 | 50.4% |

| Undergraduate | 107 | 47.3% | |

| Master | 5 | 2.2% |

| Model | Factor Content | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | GFI | IFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | CE; HC; PA; SWB | 201.309 | 97 | 2.075 | 0.069 | 0.912 | 0.902 | 0.914 |

| Three-factor model | CE + HC; PA; SWB | 481.798 | 101 | 4.770 | 0.129 | 0.680 | 0.734 | 0.685 |

| Two-factor model | CE + HC + PA; SWB | 537.891 | 103 | 5.222 | 0.137 | 0.634 | 0.715 | 0.640 |

| Single-factor model | CE + HC + PA + SWB | 652.554 | 104 | 6.275 | 0.153 | 0.539 | 0.678 | 0.545 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.560 | 0.497 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 2. Education | 1.520 | 0.543 | 0.053 | 1.000 | |||||

| 3. Age | 1.290 | 0.543 | 0.090 | −0.010 | 1.000 | ||||

| 4. Career expectations | 3.758 | 0.662 | 0.067 | 0.111 | −0.119 | 1.000 | |||

| 5. Human capital | 3.268 | 0.709 | 0.183 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.044 | 0.291 ** | 1.000 | ||

| 6. Problem-solving ability | 3.502 | 0.664 | 0.148 * | 0.189 ** | −0.065 | 0.387 ** | 0.441 ** | 1.000 | |

| 7. Social withdrawal behavior | 2.792 | 0.724 | −0.017 | −0.163 * | 0.014 | −0.179 ** | −0.252 ** | −0.343 ** | 1.000 |

| Regression Equation | Fit Coefficient | Significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variable | Predictive Variable | R | R2 | F | Β | t |

| Human capital | Career expectations | 0.432 | 0.187 | 12.693 | 0.277 | 4.201 *** |

| Problem-solving ability | Career expectations | 0.526 | 0.277 | 16.841 | 0.273 | 4.504 *** |

| Human capital | 0.314 | 5.269 *** | ||||

| Social withdrawal behavior | Career expectations | 0.373 | 0.139 | 5.912 | −0.041 | −0.544 |

| Human capital | −0.106 | −1.413 | ||||

| Problem-solving ability | −0.301 | −3.745 *** | ||||

| PATH | Effect | Boot SE | Boot CI Lower Bound | Boot CI Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X→Y | −0.041 | 0.076 | −0.190 | 0.108 |

| X→M1→Y | −0.030 | 0.025 | −0.086 | 0.014 |

| X→M2→Y | −0.082 | 0.037 | −0.166 | −0.024 |

| X→M1→M2→Y | −0.026 | 0.012 | −0.054 | −0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, K.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M. How Do Career Expectations Affect the Social Withdrawal Behavior of Graduates Not in Employment, Education, or Training (NEETs)? The Chain Mediating Role of Human Capital and Problem-Solving Ability. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040506

Xu K, Zhang D, Wang M. How Do Career Expectations Affect the Social Withdrawal Behavior of Graduates Not in Employment, Education, or Training (NEETs)? The Chain Mediating Role of Human Capital and Problem-Solving Ability. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):506. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040506

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Ke, Dandan Zhang, and Minghui Wang. 2025. "How Do Career Expectations Affect the Social Withdrawal Behavior of Graduates Not in Employment, Education, or Training (NEETs)? The Chain Mediating Role of Human Capital and Problem-Solving Ability" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040506

APA StyleXu, K., Zhang, D., & Wang, M. (2025). How Do Career Expectations Affect the Social Withdrawal Behavior of Graduates Not in Employment, Education, or Training (NEETs)? The Chain Mediating Role of Human Capital and Problem-Solving Ability. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040506