The Synergy of School Climate, Motivation, and Academic Emotions: A Predictive Model for Learning Strategies and Reading Comprehension

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Academic Emotions and Learning Outcomes

1.2. The Role of the Classroom Environment in Motivation and Emotion

1.3. School as a Caring Community

1.4. Reading Comprehension and Learning Strategies

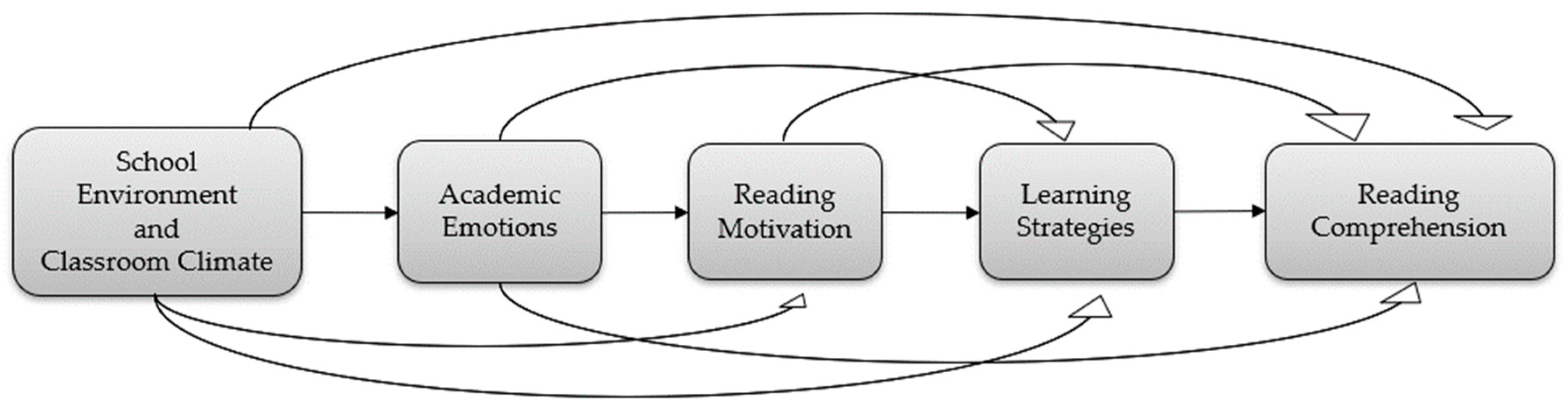

1.5. Integrating Environment, Emotion, and Cognition: Toward a Conceptual Model

1.6. The Present Study: Testing a Theoretical Pathway Model

- -

- School Environment and Academic Emotions: Students who perceive their school as a caring and supportive community and experience a positive learning climate will report higher positive academic emotions and lower negative academic emotions, aligning with theories emphasizing the role of supportive educational environments in emotional well-being and academic engagement (Battistich et al., 2000; Pekrun, 2006).

- -

- Academic Emotions and Motivation: Positive academic emotions will be positively associated with both intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation, while negative emotions will be linked to lower motivation levels. This is consistent with research suggesting that positive emotions enhance motivation and engagement, while negative emotions contribute to disengagement (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2012; Wigfield & Guthrie, 1997).

- -

- Motivation and Learning Strategies: Intrinsic motivation will be positively related to the application of in-depth learning strategies, whereas extrinsic motivation will be more associated with surface learning strategies. Students with intrinsic motivation are more likely to engage in deep-level text processing, while extrinsically motivated students tend to adopt memorization-based approaches (Nolen & Haladyna, 1990; Ryan & Deci, 2000).

- -

- Learning Strategies and Reading Comprehension: The use of in-depth learning strategies will be positively associated with higher reading comprehension scores, while the absence of learning strategies will negatively impact reading comprehension. This supports research indicating that effective strategy use enhances comprehension, whereas a lack of strategies impairs performance (Greensfeld & Nevo, 2017).

- -

- What are the direct and indirect pathways through which environmental, emotional, and motivational factors shape students’ reading comprehension?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

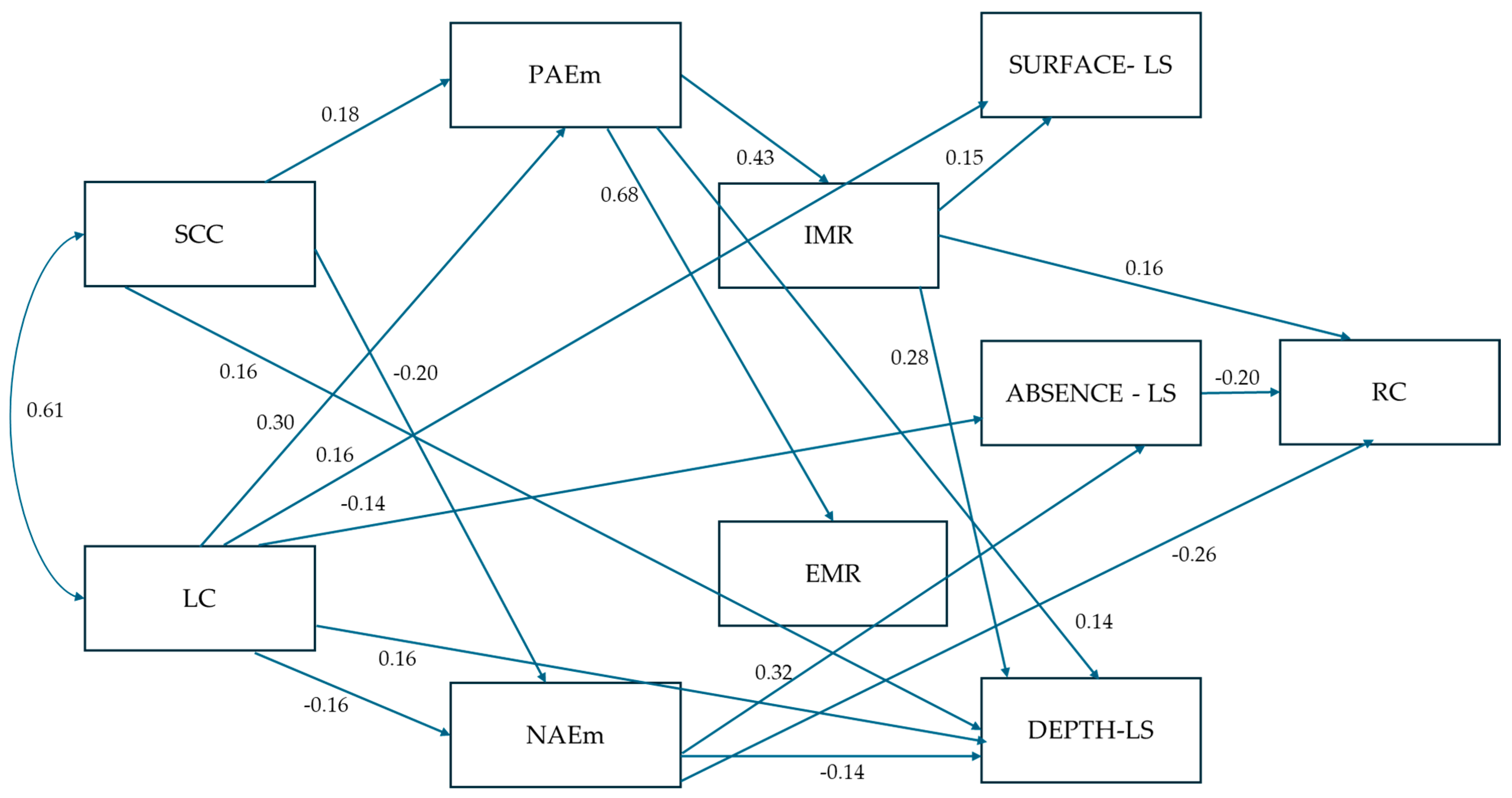

3.2. Path Analysis Model

3.2.1. Direct Effects of the Variables

3.2.2. Indirect Effects of the Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. School Environment and Academic Emotions

4.2. Academic Emotions and Motivation for Reading

4.3. Reading Motivation, Learning Strategies, and Reading Comprehension

4.4. Direct and Indirect Effects of Environmental and Psychological Variables

4.5. Summary and Limitations

5. Concluding Remarks and Implications for Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Predictor | On Outcome Variable | b | S.E. | Beta | Critical Ratio | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects of learning environments | ||||||

| School as a caring community | Positive emotions | 0.322 | 0.116 | 0.183 | 2.779 | 0.005 |

| Negative emotions | −0.337 | 0.118 | −0.197 | −2.848 | 0.004 | |

| Intrinsic read. motivation | 0.036 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.742 | 0.458 | |

| Extrinsic read. motivation | −0.038 | 0.053 | −0.04 | −0.719 | 0.472 | |

| Surface LS | 0.073 | 0.076 | 0.064 | 0.961 | 0.336 | |

| Absence LS | −0.067 | 0.086 | −0.054 | −0.777 | 0.437 | |

| Depth LS | 0.145 | 0.055 | 0.156 | 2.633 | 0.008 | |

| Reading comprehension | −0.929 | 0.738 | −0.087 | −1.259 | 0.208 | |

| Learning climate | Positive emotions | 0.293 | 0.065 | 0.299 | 4.539 | <0.001 |

| Negative emotions | −0.155 | 0.066 | −0.163 | −2.358 | 0.018 | |

| Intrinsic read. motivation | 0.027 | 0.028 | 0.064 | 0.972 | 0.331 | |

| Extrinsic read. motivation | 0.023 | 0.03 | 0.043 | 0.764 | 0.445 | |

| Surface LS | 0.101 | 0.043 | 0.158 | 2.354 | 0.019 | |

| Absence LS | −0.097 | 0.049 | −0.141 | −1.991 | 0.047 | |

| Depth LS | 0.082 | 0.031 | 0.158 | 2.638 | 0.008 | |

| Reading comprehension | 0.596 | 0.419 | 0.101 | 1.423 | 0.155 | |

| Direct effects of academic emotions | ||||||

| Positive emotions | Intrinsic read. motivation | 0.184 | 0.025 | 0.429 | 7.277 | <0.001 |

| Extrinsic read. motivation | 0.37 | 0.027 | 0.685 | 13.529 | <0.001 | |

| Surface LS | 0.091 | 0.051 | 0.14 | 1.79 | 0.073 | |

| Absence LS | 0.071 | 0.058 | 0.1 | 1.224 | 0.221 | |

| Depth LS | 0.077 | 0.037 | 0.145 | 2.081 | 0.037 | |

| Reading comprehension | −0.873 | 0.494 | −0.144 | −1.766 | 0.077 | |

| Negative emotions | Extrinsic read. motivation | 0.031 | 0.027 | 0.055 | 1.141 | 0.254 |

| Intrinsic read. motivation | −0.018 | 0.025 | −0.041 | −0.739 | 0.46 | |

| Surface LS | −0.039 | 0.039 | −0.058 | −1.009 | 0.313 | |

| Absence LS | 0.236 | 0.044 | 0.325 | 5.361 | <0.001 | |

| Depth LS | −0.075 | 0.028 | −0.137 | −2.676 | 0.007 | |

| Reading comprehension | −1.602 | 0.393 | −0.257 | −4.072 | <0.001 | |

| Direct effects of reading motivation | ||||||

| Intrinsic reading motivation | Surface LS | 0.233 | 0.094 | 0.153 | 2.493 | 0.013 |

| Depth LS | 0.342 | 0.068 | 0.277 | 5.064 | <0.001 | |

| Absence LS | 0.039 | 0.106 | 0.024 | 0.369 | 0.712 | |

| Reading comprehension | 2.278 | 0.934 | 0.161 | 2.438 | 0.015 | |

| Extrinsic reading motivation | Depth LS | 0.002 | 0.062 | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.976 |

| Surface LS | 0.106 | 0.087 | 0.088 | 1.229 | 0.219 | |

| Absence LS | 0.087 | 0.098 | 0.067 | 0.886 | 0.376 | |

| Reading comprehension | −1.199 | 0.832 | −0.107 | −1.44 | 0.15 | |

| Direct effects of learning strategies | ||||||

| Absence of learn. strategies | Reading comprehension | −1.693 | 0.5 | −0.197 | −3.387 | <0.001 |

| Depth learning strategies | Reading comprehension | 0.813 | 0.941 | 0.071 | 0.864 | 0.387 |

| Surface learning strategies | Reading comprehension | −0.8 | 0.689 | −0.086 | −1.161 | 0.246 |

| Predictor | On Outcome Variable | b | S.E. | Beta | 90% Lower CI | 90% Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effects of learning environments | ||||||

| School as a caring community | Extrinsic read. motivation | 0.109 | 0.045 | 0.047 | 0.036 | 0.183 |

| Intrinsic read. motivation | 0.065 | 0.026 | 0.034 | 0.027 | 0.114 | |

| Depth LS | 0.085 | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.037 | 0.146 | |

| Absence LS | −0.046 | 0.032 | 0.026 | −0.109 | −0.001 | |

| Surface LS | 0.074 | 0.035 | 0.03 | 0.022 | 0.139 | |

| Reading comprehension | 0.665 | 0.442 | 0.04 | 0.014 | 1.489 | |

| Learning climate | Extrinsic read. motivation | 0.104 | 0.026 | 0.045 | 0.061 | 0.15 |

| Intrinsic read. motivation | 0.057 | 0.015 | 0.033 | 0.035 | 0.084 | |

| Depth LS | 0.063 | 0.017 | 0.032 | 0.037 | 0.094 | |

| Absence LS | −0.002 | 0.022 | 0.031 | −0.037 | 0.036 | |

| Surface LS | 0.066 | 0.021 | 0.031 | 0.035 | 0.105 | |

| Reading comprehension | 0.183 | 0.243 | 0.041 | −0.175 | 0.625 | |

| Indirect effects of academic emotions | ||||||

| Positive emotions | Depth LS | 0.064 | 0.023 | 0.044 | 0.026 | 0.103 |

| Absence LS | 0.039 | 0.036 | 0.051 | −0.019 | 0.099 | |

| Surface LS | 0.082 | 0.035 | 0.053 | 0.023 | 0.139 | |

| Reading comprehension | −0.236 | 0.341 | 0.057 | −0.778 | 0.348 | |

| Negative emotions | Depth LS | −0.006 | 0.01 | 0.019 | −0.025 | 0.009 |

| Absence LS | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.009 | −0.007 | 0.015 | |

| Surface LS | −0.001 | 0.01 | 0.015 | −0.018 | 0.015 | |

| Reading comprehension | −0.515 | 0.166 | 0.026 | −0.783 | −0.258 | |

| Indirect effects of reading motivation | ||||||

| Intrinsic reading motivation | Reading comprehension | 0.025 | 0.355 | 0.025 | −0.583 | 0.578 |

| Extrinsic reading motivation | Reading comprehension | −0.231 | 0.204 | 0.018 | −0.58 | 0.066 |

References

- Abolmaali, K., & Mahmudi, R. (2013). The prediction of academic achievement based on resilience and perception of the classroom environment. Open Science Journal of Education, 1(1), 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Haerens, L., Soenens, B., Fontaine, J. R. J., & Reeve, J. (2019). Toward an integrative and fine-grained insight in motivating and demotivating teaching styles: The merits of a circumplex approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(3), 497–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainley, M., Corrigan, M., & Richardson, N. (2005). Students, tasks and emotions: Identifying the contribution of emotions to students’ reading of popular culture and popular science texts. Learning and Instruction, 15(5), 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, P. A. (2004). A model of domain learning: Reinterpreting expertise as a multidimensional, multistage process. In D. Y. Dai, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Motivation, emotion, and cognition: Integrative perspectives on intellectual functioning and development (pp. 273–298). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anttila, H., Pyhalto, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2018). Socially embedded academic emotions in school. Journal of Education and Learning, 7(3), 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arbuckle, J. L. (2013). IBM SPSS Amos [computer program] (Version 22.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Arhar, J. M., & Kromrey, J. D. (1993, April 12). Interdisciplinary teaming in the middle level school: Creating a sense of belonging for at-risk middle level students. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Atlanta, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Babad, E. Y. (2009). The social psychology of the classroom. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Battistich, V., Schaps, E., Watson, M., Solomon, D., & Lewis, C. (2000). Effects of the child development project on students’ drug use and other problem behaviors. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 21(1), 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistich, V., Solomon, D., Watson, M., & Schaps, E. (1997). Caring school communities. Educational Psychologist, 32(3), 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M., McElvany, N., & Kortenbruck, M. (2010). Intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation as predictors of reading literacy: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A. S., & Driscoll, M. E. (1988). The school as community: Theoretical foundations, contextual influences, and consequences for students and teachers. Center on Effective Secondary Schools, University of Wisconsin. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau, J. S., Howard, J. L., Chong, J. X. Y., & Guay, F. (2022). Pathways to student motivation: A meta-analysis of antecedents of autonomous and controlled motivations. Review of Educational Research, 92(1), 46–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, K., & Oakhill, J. V. (1999). Inference making ability and its relation to comprehension failure in young children. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 11(5/6), 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J. W., Tunmer, W. E., & Prochnow, J. E. (2000). Early reading-related skills and performance, reading self-concept, and the development of academic self-concept: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(4), 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Huang, Z., Peng, B., & Hu, H. (2025). Unpacking the relationship between adolescents’ perceived school climate and negative emotions: The chain mediating roles of school belonging and social avoidance and distress. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrysochoou, E. (2006). H συμβολή της εργαζόμενης μνήμης στην ακουστική κατανόηση παιδιών προσχολικής και σχολικής ηλικίας [Working memory contributions to young children’s listening comprehension] [Doctoral Dissertation, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki]. Available online: https://thesis.ekt.gr/thesisBookReader/id/14127?lang=el#page/1/mode/2up (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Chrysochoou, E., & Bablekou, Z. (2011). Phonological loop and central executive contributions to oral comprehension skills of 5.5 to 9.5 years old children. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(4), 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysochoou, E., Bablekou, Z., & Tsigilis, N. (2011). Working memory contributions to reading comprehension components in middle childhood children. The American Journal of Psychology, 124(3), 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J. P. (1990). Context, self, and action: A motivational analysis of self-system processes across the life span. In D. Cicchetti, & M. Beeghly (Eds.), The self in transition: Infancy to childhood (pp. 61–97). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, M. C., Day, S. L., Phillips, B., Sparapani, N., Ingebrand, S. W., McLean, L., Barrus, A., & Kaschak, M. P. (2016). Reciprocal effects of self-regulation, semantic knowledge, and reading comprehension in early elementary school. Child Development, 87(6), 1813–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cromley, J. G., & Azevedo, R. (2007). Testing and refining the direct and inferential mediation model of reading comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, L. M., Stupnisky, R. H., Pekrun, R., Haynes, T. L., Perry, R. P., & Newall, N. E. (2009). A longitudinal analysis of achievement goals: From affective antecedents to emotional effects and achievement outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(4), 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘What’ and ‘Why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Naeghel, J., Van Keer, H., Vansteenkiste, M., & Rosseel, Y. (2012). The relation between elementary students’ recreational and academic reading motivation, reading frequency, engagement, and comprehension: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermitzaki, I. (2025). Fostering elementary school students’ self-regulation skills in reading comprehension: Effects on text comprehension, strategy use, and self-efficacy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermitzaki, I., & Papakosma, N. (2020). Strategies for reading comprehension in elementary school students: Their use and relations with students’ motivation and emotions. Scientific Annals-School of Psychology AUTh, 13, 56–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dettmers, S., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., & Pekrun, R. (2011). Students’ emotions during homework in mathematics: Testing a theoretical model of antecedents and achievement outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewulf, L., Van Braak, J., & Van Houtte, M. (2022). Examining reading comprehension in disadvantaged segregated classes. The role of class composition, teacher trust, and teaching learning strategies. Research Papers in Education, 37(5), 686–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leo, I., Muis, K. R., Singh, C. A., & Psaradellis, C. (2019). Curiosity… confusion? frustration! The role and sequencing of emotions during mathematics problem solving. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulou, P., Filippatou, D., Diakogiorgis, K., Ralli, A., Roussos, P., & Chrysochou, E. (2016, October 20–23). The contribution of psycho-emotional factors to reading comprehension and written language production at school age. 5th Panhellenic Conference on Developmental Psychology “Putting Together the Puzzle of Human Development: Bridges with Society and Education”, Volos, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitropoulou, P., Lampropoulou, A., Lykitsakou, K., & Chatzichristou, C. (2012). Ερωτηματολόγιο ’Το Σχολείο ως Κοινότητα που Νοιάζεται και Φροντίζει [Questionnaire ‘School as a caring community profile-II (SCCP-II)’ (Greek adaptation)]. In A. Stalikas, S. Triliva, & P. Roussi (Eds.), Τα Ψυχομετρικά Εργαλεία στην Ελλάδα [The psychometric tools in Greece] (2nd ed., pp. 848–849). Pedio Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dinsmore, D. L. (2017). Toward a dynamic, multidimensional research framework for strategic processing. Educational Psychology Review, 29(2), 235–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droop, M., Van Elsäcker, W., Voeten, M. J. M., & Verhoeven, L. (2016). Long-term effects of strategic reading instruction in the intermediate elementary grades. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 9(1), 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Durkin, D. (1993). Teaching them to read (6th ed.). Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Efklides, A. (2011). Interactions of metacognition with motivation and affect in self-regulated learning. The MASRL model. Educational Psychologist, 46, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efklides, A., & Schwartz, B. L. (2024). Revisiting the metacognitive and affective model of self-regulated learning (MASRL): Origins, development, and future directions. Educational Psychology Review, 36(2), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbro, C., & Buch-Iversen, I. (2013). Activation of background knowledge for inference making: Effects on reading comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 17(6), 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, H. C., Ottaway, S. A., Varner, L. J., Becker, A. S., & Moore, B. A. (1997). Emotion, motivation, and text comprehension: The detection of contradictions in passages. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 126(2), 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, H. C., Varner, L. J., Becker, A. S., & Ottaway, S. A. (1995). Emotion and prior knowledge in memory and judged comprehension of ambiguous stories. Cognition & Emotion, 9(4), 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J. H. (1987). Speculations about the nature and development of metacognition. In F. Weinert, & R. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, motivation and understanding (pp. 21–29). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Fong Lam, U., Chen, W.-W., Zhang, J., & Liang, T. (2015). It feels good to learn where I belong: School belonging, academic emotions, and academic achievement in adolescents. School Psychology International, 36(4), 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froiland, J. M., & Oros, E. (2014). Intrinsic motivation, perceived competence and classroom engagement as longitudinal predictors of adolescent reading achievement. Educational Psychology, 34(2), 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, R. D., Sweetland, S. R., & Hoy, W. K. (2000). Academic emphasis of urban elementary schools and student achievement in reading and mathematics: A multilevel analysis. Educational Administration Quarterly, 36(5), 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Stockinger, K., Lipnevich, A. A., Stempfer, L., & Pekrun, R. (2023). Emotions in education. In R. Tierney, F. Rizvi, & K. Ercikan (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (4th ed., pp. 149–161). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonida, E. N., & Leontari, A. (2012). Χρήση Στρατηγικών [Learning strategies questionnaire (Greek)]. In A. Stalikas, S. Triliva, & P. Roussi (Eds.), Τα Ψυχομετρικά Εργαλεία στην Ελλάδα [The psychometric tools in Greece] (2nd ed.). Pedio Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- González, A., & Paoloni, P. V. (2014). Self-determination, behavioral engagement, disaffection, and academic performance: A mediational analysis. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 17, E82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C. (1993). Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: Relationships to motivation and achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 13(1), 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2018). An examination of the design principles underlying a self-regulated strategy development study. Journal of Writing Research, 10(2), 139–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, P. A., Reavis, R. D., Keane, S. P., & Calkins, S. D. (2007). The role of emotion regulation in children’s early academic success. Journal of School Psychology, 45(1), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greensfeld, H., & Nevo, E. (2017). To use or not to use, that is the question: On students’ encounters with a library of examples. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1323381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J. T., Van Meter, P., McCann, A. D., Wigfield, A., Bennett, L., Poundstone, C. C., Rice, M. E., Faibisch, F. M., Hunt, B., & Mitchell, A. M. (1996). Growth of literacy engagement: Changes in motivations and strategies during concept-oriented reading instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 31(3), 306–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (3rd ed., pp. 403–422). Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2018). Literacy engagement and motivation: Rationale, research, teaching and assessment. In D. Lapp, & D. Fisher (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching the English language arts (4th ed., pp. 57–84). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Metsala, J. L., & Cox, K. E. (1999). Motivational and cognitive predictors of text comprehension and reading amount. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(3), 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., & You, W. (2012). Instructional contexts for engagement and achievement in reading. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 601–634). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagenauer, G., Hascher, T., & Volet, S. E. (2015). Teacher emotions in the classroom: Associations with students’ engagement, classroom discipline and the interpersonal teacher-student relationship. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30(4), 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzichristou, C., Dimitropoulou, P., Lykitsakou, K., & Lampropoulou, A. (2020). Promoting school community well-being: Implementation of a system-level intervention program. Psychology: The Journal of the Hellenic Psychological Society, 16(4), 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayenga, A. O., & Corpus, J. H. (2010). Profiles of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: A person-centered approach to motivation and achievement in middle school. Motivation and Emotion, 34(4), 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2015). IBM SPSS statistics for Windows (Version 23.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H., Kim, E. J., & Reeve, J. (2016). Why students become more engaged or more disengaged during the semester: A self-determination theory dual-process model. Learning and Instruction, 43, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, L. Y., & Liu, W. C. (2012). 2 × 2 Achievement goals and achievement emotions: A cluster analysis of students’ motivation. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 27(1), 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendeou, P., McMaster, K. L., & Christ, T. J. (2016). Reading comprehension: Core components and processes. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C., & Pekrun, R. (2014). Emotions and motivation in learning and performance. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. Elen, & M. J. Bishop (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 65–75). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. B., & Gaerlan, M. J. M. (2014). High self-control predicts more positive emotions, better engagement, and higher achievement in school. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29(1), 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintsch, W. (2009). Learning and constructivism. In S. Tobias, & T. M. Duffy (Eds.), Constructivist instruction: Success or failure? (pp. 223–241) Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, K. (2009). Reading motivation, perceptions of reading instruction and reading amount: A comparison of junior and senior secondary students in Hong Kong. Journal of Research in Reading, 32(4), 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X., Zhu, X., & Zhao, P. (2022). The mediating effects of reading amount and strategy use in the relationship between intrinsic reading motivation and comprehension: Differences between Grade 4 and Grade 6 students. Reading and Writing, 35(5), 1091–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lickona, T., & Davidson, M. (2012). School as a caring community profile-II (SCCP-II): A survey of students, staff, and parents scale descriptions. In A. Stalikas, S. Triliva, & P. Roussi (Eds.), Psychometric tools in Greece (2nd ed., pp. 848–849). Pedio. [Google Scholar]

- Linnenbrink, E. A. (2007). The role of affect in student learning. In Emotion in education (pp. 107–124). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J. A. R., Piasta, S. B., Justice, L. M., Schatschneider, C., & Petrill, S. (2011). Children’s attendance rates and quality of teacher-child interactions in at-risk preschool classrooms: Contribution to children’s expressive language growth. Child & Youth Care Forum, 40(6), 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohbeck, A., & Moschner, B. (2022). Motivational regulation strategies, academic self-concept, and cognitive learning strategies of university students: Does academic self-concept play an interactive role? European Journal of Psychology of Education, 37(4), 1217–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magi, K., Mannamaa, M., & Kikas, E. (2016). Profiles of self-regulation in elementary grades: Relations to math and reading skills. Learning & Individual Differences, 51, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, C. G., Roe, A., & Blikstad-Balas, M. (2019). To what extent and how are reading comprehension strategies part of language arts instruction? A study of lower secondary classrooms. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(2), 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, L. H. (2013). Teaching students who struggle with learning to think before, while, and after reading: Effects of self-regulated strategy development instruction. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 29, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S., Reynolds, K. J., Lee, E., Subasic, E., & Bromhead, D. (2017). The impact of school climate and school identification on academic achievement: Multilevel modeling with student and teacher data. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, M. A., & Einstein, G. O. (2000). Strategic and automatic processes in prospective memory retrieval: A multiprocess framework. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 14(7), S127–S144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meece, J. L., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Hoyle, R. H. (1988). Students’ goal orientations and cognitive engagement in classroom activities. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(4), 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, C., Ronconi, L., & De Beni, R. (2014). What makes a good student? How emotions, self-regulated learning, and motivation contribute to academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, K., & Reichard, C. A. (2002). Assessing students’ metacognitive awareness of reading strategies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A. L. (2015). Reading comprehension: A research review of cognitive skills, strategies, and interventions. Available online: https://cdndownload.learningrx.com/reading-comprehension-research-paper.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Morgan, P. L., & Fuchs, D. (2007). Is there a bidirectional relationship between children’s reading skills and reading motivation? Exceptional Children, 73(2), 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, A., & Michou, A. (2011). Self-determined motivation and social achievement goals in children’s emotions. Educational Psychology, 31(1), 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucherah, W., & Yoder, A. (2008). Motivation for reading and middle school students’ performance on standardized testing in reading. Reading Psychology, 29(3), 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muijselaar, M. L., Swart, N. M., Steenbeek-Planting, E. G., Droop, M., Verhoeven, L., & de Jong, P. F. (2017). Developmental relations between reading comprehension and reading strategies. Scientific Studies of Reading, 21(3), 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38(1), 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naceur, A., & Schiefele, U. (2005). Motivation and learning—The role of interest in construction of representation of text and long-term retention: Inter- and intraindividual analyses. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 20(2), 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejadihassan, S., & Arabmofrad, A. (2016). A review of relationship between self-regulation and reading comprehension. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 6(4), 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen, S. B., & Haladyna, T. M. (1990). Personal and environmental influences on students’ beliefs about effective study strategies. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 15(2), 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakhill, J. (1984). Inferential and memory skills in children’s comprehension of stories. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 54(1), 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obergriesser, S., & Stoeger, H. (2020). Students’ emotions of enjoyment and boredom and their use of cognitive learning strategies—How do they affect one another? Learning and Instruction, 66, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoloni, P. V. R. (2014). Emotions in academic contexts: Theoretical perspectives and implications for educational practice in college. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 12(3), 567–596. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, L. S. (2004). What every teacher needs to know about comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 58(3), 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, F., Mata, L., Monteiro, V., Sanches, C., & Pekrun, R. (2015). The achievement emotions questionnaire: Validation for pre-adolescent students. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12(4), 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (1992). The impact of emotions on learning and achievement: Towards a theory of cognitive/motivational mediators. Applied Psychology, 41(4), 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2000). A social-cognitive, control-value theory of achievement emotions. In Advances in psychology (Vol. 131, pp. 143–163). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2019). Achievement emotions: A control-value theory perspective. In R. Patulny, A. Bellocchi, R. E. Olson, S. Khorana, J. McKenzie, & M. Peterie (Eds.), Emotions in late modernity (1st ed., pp. 142–157). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2022). Emotions in reading and learning from texts: Progress and open problems. Discourse Processes, 59(1–2), 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2024). Control-value theory: From achievement emotion to a general theory of human emotions. Educational Psychology Review, 36(3), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Elliot, A. J., & Maier, M. A. (2006). Achievement goals and discrete achievement emotions: A theoretical model and prospective test. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(3), 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2007). The control-value theory of achievement emotions. In Emotion in education (pp. 13–36). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Barchfeld, P., & Perry, R. P. (2011). Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Perry, R. P., Kramer, K., Hochstadt, M., & Molfenter, S. (2004). Beyond test anxiety: Development and validation of the test emotions questionnaire (TEQ). Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 17(3), 287–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Hall, N. C., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Boredom and academic achievement: Testing a model of reciprocal causation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(3), 696–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Marsh, H. W., Elliot, A. J., Stockinger, K., Perry, R. P., Vogl, E., Goetz, T., van Tilburg, W. A. P., Lüdtke, O., & Vispoel, W. P. (2023). A three-dimensional taxonomy of achievement emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(1), 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Control-value theory of achievement emotions. In R. Pekrun, & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 120–141). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, A. P., Del Re, E., Nestor, P. G., McCarley, R. W., Gonçalves, Ó. F., & Niznikiewicz, M. (2013). Interactions between mood and the structure of semantic memory: Event-related potentials evidence. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(5), 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R. (2002). The role of metacognitive knowledge in learning, teaching, and assessing. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16(4), 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, M., & Afflerbach, P. (1995). Verbal protocols of reading: The nature of constructively responsive reading. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Pressley, M., & Gaskins, I. W. (2006). Metacognitively Competent Reading Comprehension Is Constructively Responsive Reading: How Can Such Reading Be Developed in Students? Metacognition and Learning, 1, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, D. W., Sander, P., & Larkin, D. (2013). Academic self-efficacy in study-related skills and behaviours: Relations with learning-related emotions and academic success. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(4), 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putwain, D. W., Schmitz, E. A., Wood, P., & Pekrun, R. (2021). The role of achievement emotions in primary school mathematics: Control–value antecedents and achievement outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranellucci, J., Hall, N. C., & Goetz, T. (2015). Achievement goals, emotions, learning, and performance: A process model. Motivation Science, 1(2), 98–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Cheon, S. H. (2021). Autonomy-supportive teaching: Its malleability, benefits, and potential to improve educational practice. Educational Psychologist, 56(1), 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retelsdorf, J., Köller, O., & Möller, J. (2011). On the effects of motivation on reading performance growth in secondary school. Learning and Instruction, 21(4), 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W., Horn, A., & Battistich, V. (1995, April 18). Assessing students’ and teachers’ sense of the school as a caring community. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rubie-Davies, C. (2014). Teachers’ instructional beliefs and the classroom climate. In H. Fives, & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 266–283). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rubie-Davies, C., Asil, M., & Teo, T. (2016). Assessing measurement invariance of the student personal perception of classroom climate across different ethnic groups. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(5), 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelstuen, M. S., & Bråten, I. (2005). Decoding, knowledge, and strategies in comprehension of expository text. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 46(2), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K. R. (2009). The dynamic architecture of emotion: Evidence for the component process model. Cognition & Emotion, 23(7), 1307–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefele, U. (1990). The influence of topic interest, prior knowledge, and cognitive capabilities on text comprehension. In J. M. Pieters, K. Breuer, & P. R.-J. Simons (Eds.), Learning environments: Contributions from Dutch and German research (pp. 323–338). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefele, U. (2009). Situational and individual interest. In K. R. Wentzel, & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 197–222). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Schiefele, U., Schaffner, E., Möller, J., & Wigfield, A. (2012). Dimensions of reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(4), 427–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefele, U., Stutz, F., & Schaffner, E. (2016). Longitudinal relations between reading motivation and reading comprehension in the early elementary grades. Learning and Individual Differences, 51, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H. (1991). Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 26(3), 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., Pintrich, P. R., & Meece, J. L. (2010). Τα κίνητρα στην εκπαίδευση [Greek] (N. Makris, & D. Pneumatikos, Eds.; M. Koulentianou, Trans.). Gutenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2012). Self-regulation and learning. In I. Weiner (Ed.), Handbook of psychology, educational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 59–78). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, P. A., & Pekrun, R. (2007). Emotion in education. Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schünemann, N., Spörer, N., & Brunstein, J. C. (2013). Integrating self-regulation in whole-class reciprocal teaching: A moderator–mediator analysis of incremental effects on fifth graders’ reading comprehension. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(4), 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrimin, S., & Mason, L. (2015). Does mood influence text processing and comprehension? Evidence from an eye-movement study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(3), 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedek, G., & Von Hecker, U. (2004). Effects of subclinical depression and aging on generative reasoning about linear orders: Same or different processing limitations? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133(2), 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shochet, I. M., Dadds, M. R., Ham, D., & Montague, R. (2006). School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: Results of a community prediction study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, D., Watson, M. S., Delucchi, K. L., Schaps, E., & Battistich, V. (1988). Enhancing children’s prosocial behavior in the classroom. American Educational Research Journal, 25(4), 527–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spörer, N., & Schünemann, N. (2014). Improvements of self-regulation procedures for fifth graders’ reading competence: Analyzing effects on reading comprehension, reading strategy performance, and motivation for reading. Learning and Instruction, 33, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew Effects in Reading: Some Consequences of Individual Differences in the Acquisition of Literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21, 360–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutz, F., Schaffner, E., & Schiefele, U. (2016). Relations among reading motivation, reading amount, and reading comprehension in the early elementary grades. Learning and Individual Differences, 45, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Wang, J., Dong, Y., Zheng, H., Yang, J., Zhao, Y., & Dong, W. (2021). The relationship between reading strategy and reading comprehension: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 635289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, M. (2008). Talking sense about learning strategies. RELC Journal, 39(2), 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeny, K., & Vohs, K. D. (2012). On near misses and completed tasks: The nature of relief. Psychological Science, 23(5), 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šabec, T. (2022). Reading motivation and reading strategies in the primary school classroom. European Journal of Literature, Language and Linguistics Studies, 6(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, A., Tonks, S. M., Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (2009). Effects of motivational and cognitive variables on reading comprehension. Reading and Writing, 22(1), 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J., Mao, J., Jiang, Y., & Gao, M. (2021). The influence of academic emotions on learning effects: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G., Jungert, T., Mageau, G. A., Schattke, K., Dedic, H., Rosenfield, S., & Koestner, R. (2014). A self-determination theory approach to predicting school achievement over time: The unique role of intrinsic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39(4), 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toste, J. R., Didion, L., Peng, P., Filderman, M. J., & McClelland, A. M. (2020). A meta-analytic review of the relations between motivation and reading achievement for K–12 students. Review of Educational Research, 90(3), 420–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevors, G. J., Muis, K. R., Pekrun, R., Sinatra, G. M., & Muijselaar, M. M. L. (2017). Exploring the relations between epistemic beliefs, emotions, and learning from texts. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 48, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevors, G. J., Muis, K. R., Pekrun, R., Sinatra, G. M., & Winne, P. H. (2016). Identity and epistemic emotions during knowledge revision: A potential account for the backfire effect. Discourse Processes, 53(5–6), 339–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J. E., & Schallert, D. L. (2001). Expectancy–value relationships of shame reactions and shame resiliency. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(2), 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyng, C. M., Amin, H. U., Saad, M. N. M., & Malik, A. S. (2017). The influences of emotion on learning and memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tze, V. M. C., Klassen, R. M., & Daniels, L. M. (2014). Patterns of boredom and its relationship with perceived autonomy support and engagement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39(3), 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdan, T., & Schoenfelder, E. (2006). Classroom effects on student motivation: Goal structures, social relationships, and competence beliefs. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urke, H. B., Kristensen, S. M., Bøe, T., Gaspar De Matos, M., Wiium, N., Årdal, E., & Larsen, T. (2023). Perceptions of a caring school climate and mental well-being: A one-way street? Results from a random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Applied Developmental Science, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berghe, L., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Aelterman, N., Cardon, G., Tallir, I. B., & Haerens, L. (2013). Observed need-supportive and need-thwarting teaching behavior in physical education: Do teachers’ motivational orientations matter? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(5), 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Broek, P., & Espin, C. A. (2012). Connecting cognitive theory and assessment: Measuring individual differences in reading comprehension. School Psychology Review, 41(3), 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Intrinsic versus extrinsic goal contents in Self-Determination Theory: Another look at the quality of academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 41(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio, F. T., & Bernardo, A. B. I. (2013). Positive academic emotions moderate the relationship between self-regulation and academic achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(2), 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Hecker, U., & Meiser, T. (2005). Defocused attention in depressed mood: Evidence from source monitoring. Emotion, 5(4), 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. H., & Guthrie, J. T. (2004). Modeling the effects of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, amount of reading, and past reading achievement on text comprehension between U.S. and Chinese students. Reading Research Quarterly, 39(2), 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T., & Degol, J. L. (2016). School Climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 315–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T., & Holcombe, R. (2010). Adolescents’ perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 47(3), 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H. L., McDougall, P., Krygsman, A., Smith, D., Cunningham, C. E., Haltigan, J. D., & Hymel, S. (2014). School climate, peer victimization, and academic achievement: Results from a multi-informant study. School Psychology Quarterly, 29(3), 360–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. S., & Elias, H. (2011). Relationship between students’ perceptions of classroom enviroment and their motivation in learning english language. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(21), 240–250. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, C. E., Acee, T. W., & Jung, J. (2011). Self-regulation and learning strategies. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2011(126), 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, C. E., & Mayer, R. E. (1986). The teaching of learning strategies. In M. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (pp. 315–327). Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Relations of children’s motivation for reading to the amount and breadth or their reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3), 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (2010). The impact of concept-oriented reading instruction on students’ reading motivation, reading engagement, and reading comprehension. In J. L. Meece, & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Handbook on schools, schooling, and human development (pp. 463–477). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. (2012). The learning climate questionnaire (LCQ). (Adaptation: Dimitropoulou, P., Lykitsakou, K., & Chatzichristou, C.). In A. Stalikas, S. Triliva, & P. Roussi (Eds.), Psychometric tools in Greece (2nd ed., pp. 825–826). Pedio. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: A test of self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccoletti, S., Altoè, G., & Mason, L. (2020). The interplay of reading-related emotions and updating in reading comprehension performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(3), 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahid, G. (2014). Direct and indirect impact of perceived school climate upon student outcomes. Asian Social Science, 10(8), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zeidner, M. (2007). Test anxiety in educational contexts. In Emotion in education (pp. 165–184). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social-cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–39). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Positive Emotions | Negative Emotions |

|---|---|---|

| Enjoyment | 1.017 | |

| Pride | 0.771 | |

| Boredom | −0.524 | |

| Anxiety | 0.863 | |

| Hopelessness | 0.804 | |

| Anger | 0.530 | |

| Relief | 0.520 |

| Variables | #Items | Mean | SD | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 | 3.46 | 0.60 | 0.607 ** | 0.365 ** | −0.297 ** | 0.256 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.286 ** | 0.417 ** | −0.178 ** | 0.055 |

| 15 | 5.22 | 1.08 | 0.411 ** | −0.283 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.285 ** | 0.339 ** | 0.429 ** | −0.199 ** | 0.116 * | |

| 6 | 6.77 | 1.05 | −0.408 ** | 0.490 ** | 0.666 ** | 0.385 ** | 0.460 ** | −0.054 | −0.012 | ||

| 16 | 3.91 | 1.02 | −0.249 ** | −0.225 ** | −0.237 ** | −0.357 ** | 0.318 ** | −0.284 ** | |||

| 14 | 3.08 | 0.45 | 0.481 ** | 0.339 ** | 0.467 ** | −0.029 | 0.119 * | ||||

| 15 | 3.05 | 0.57 | 0.326 ** | 0.342 ** | 0.020 | −0.066 | |||||

| 4 | 3.82 | 0.69 | 0.679 ** | −0.219 ** | 0.039 | ||||||

| 14 | 3.87 | 0.56 | −0.172 ** | 0.117 * | |||||||

| 8 | 2.39 | 0.74 | −0.275 ** | ||||||||

| 10 | 25.27 | 6.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dimitropoulou, P.; Filippatou, D.; Gkoutzourela, S.; Griva, A.; Pachiti, I.; Michaelides, M. The Synergy of School Climate, Motivation, and Academic Emotions: A Predictive Model for Learning Strategies and Reading Comprehension. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040503

Dimitropoulou P, Filippatou D, Gkoutzourela S, Griva A, Pachiti I, Michaelides M. The Synergy of School Climate, Motivation, and Academic Emotions: A Predictive Model for Learning Strategies and Reading Comprehension. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):503. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040503

Chicago/Turabian StyleDimitropoulou, Panagiota, Diamanto Filippatou, Stamatia Gkoutzourela, Anthi Griva, Iouliani Pachiti, and Michalis Michaelides. 2025. "The Synergy of School Climate, Motivation, and Academic Emotions: A Predictive Model for Learning Strategies and Reading Comprehension" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040503

APA StyleDimitropoulou, P., Filippatou, D., Gkoutzourela, S., Griva, A., Pachiti, I., & Michaelides, M. (2025). The Synergy of School Climate, Motivation, and Academic Emotions: A Predictive Model for Learning Strategies and Reading Comprehension. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040503