From Rights to Responsibilities at Work: The Longitudinal Interplay of Decent Work, Flourishing, and Job Performance Across Italian Employees

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Decent Work

1.2. Analyzing Decent Work Through the Lens of COR Theory and SDT

1.3. “Gain Spirals”: Reciprocal Relationships Between Decent Work, Flourishing, and Job Performance

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure and Participants

2.2. Measures

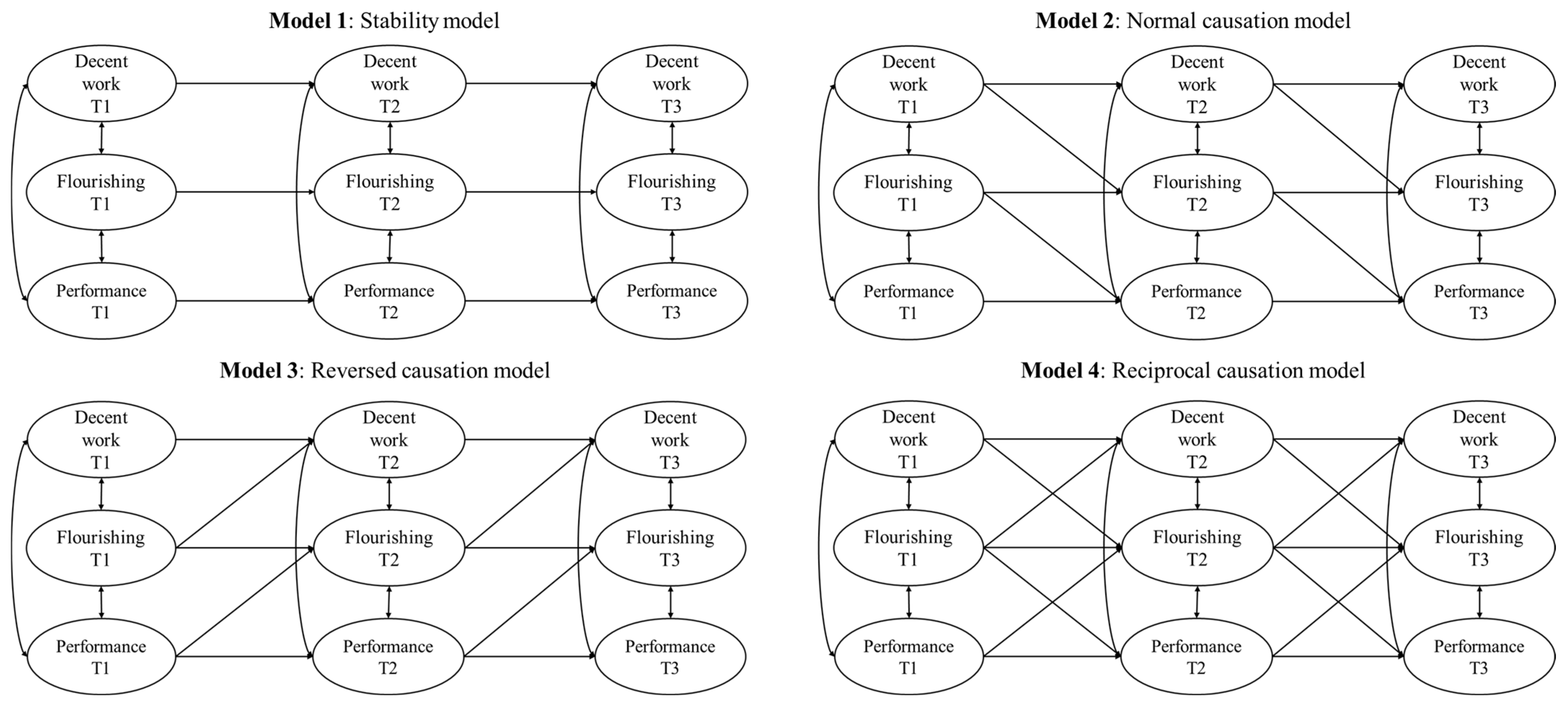

2.3. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Study Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COR | Conservation of Resources |

| SDT | Self-determination theory |

| 1 | Following the observations of an anonymous reviewer, we conducted a post hoc RMSEA-based power analysis to assess whether our sample size was adequate for the intended analyses using the web-based interface power4SEM (Jak et al., 2021). With 241 degrees of freedom, a sample of 426 participants provided sufficient power to reject an RMSEA of 1 under the hypotheses of close fit (H0 = 0.05; H1 = 0.08), not-close fit (H1 = 0.01), and exact fit (H1 = 0). These results indicate that our sample size is sufficient to ensure robust statistical power in our analyses. |

References

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job demands-resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D. L., Kenny, M. E., Di Fabio, A., & Guichard, J. (2018). Expanding the impact of the psychology of working: Engaging psychology in the struggle for decent work and human rights. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(1), 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D. L., Lysova, E. I., & Duffy, R. D. (2023). Understanding decent work and meaningful work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, D. L., Olle, C., Connors-Kellgren, A., & Diamonti, A. J. (2016). Decent work: A psychological perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, J. P., McHenry, J. J., & Wise, L. L. (1990). Modeling job performance in a population of jobs. Personnel Psychology, 43(2), 313–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, D. L., & MacCallum, R. C. (2005). Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(2), 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(4), 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Gevers, J. M. P. (2015). Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., & Rispens, S. (2014). Improving the image of student-recruited samples: A commentary. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (2013). The remarkable changes in the science of subjective well-being. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 8(6), 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D. W., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., England, J. W., Blustein, D. L., Autin, K. L., Douglass, R. P., Ferreira, J., & Santos, E. J. R. (2017). The development and initial validation of the Decent Work Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(2), 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, R. D., Blustein, D. L., Diemer, M. A., & Autin, K. L. (2016). The psychology of working theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(2), 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C. K., & Bandalos, D. L. (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8(3), 430–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., Truxillo, D. M., & Mansfield, L. R. (2012). Whistle while you work: A review of the life satisfaction literature. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1038–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data (General Data Protection Regulation). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Ferraro, T., dos Santos, N. R., Pais, L., Zappalà, S., & Moreira, J. M. (2021). The decent work questionnaire: Psychometric properties of the Italian version. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 29(2), 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, T., Moreira, J. M., Dos Santos, N. R., Pais, L., & Sedmak, C. (2018a). Decent work, work motivation and psychological capital: An empirical research. Work, 60(2), 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, T., Pais, L., Rebelo Dos Santos, N., & Moreira, J. M. (2018b). The decent work questionnaire: Development and validation in two samples of knowledge workers. International Labour Review, 157(2), 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, M., Pais, L., Mónico, L., Dos Santos, N. R., Ferraro, T., & Berger, R. (2021). Decent work and work engagement: A profile study with academic personnel. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16(3), 917–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakanen, J. J., Peeters, M. C. W., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2018). Different types of employee well-being across time and their relationships with job crafting. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J. J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2012). Do burnout and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 141(2–3), 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. (1999, June 1–17). Report of the director-general: Decent work. International Labour Conference, 87th Session, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. (2015). Decent work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/topics/decent-work (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Jak, S., Jorgensen, T. D., Verdam, M. G. E., Oort, F. J., & Elffers, L. (2021). Analytical power calculations for structural equation modeling: A tutorial and Shiny app. Behavior Research Methods, 53(4), 1385–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L., Xu, X., Zubielevitch, E., & Sibley, C. G. (2025). The reciprocal within-person relationship between job insecurity and life satisfaction: Testing loss and gain spirals with two large-scale longitudinal studies. Applied Psychology, 74(1), e12599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R. C., Barber, C., Beck, A., Berglund, P., Cleary, P. D., McKenas, D., Pronk, N., Simon, G., Stang, P., Ustun, T. B., & Wang, P. (2003). The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ). Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 45(2), 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. M., & Annas, J. (2009). Feeling good and functioning well: Distinctive concepts in ancient philosophy and contemporary science. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(3), 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W., Kolb, J. A., & Kim, T. (2012). The relationship between work engagement and performance. Human Resource Development Review, 12(3), 248–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, M., & Razmus, W. (2019). When I feel my business succeeds, I flourish: Reciprocal relationships between positive orientation, work engagement, and entrepreneurial success. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(8), 2711–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leka, S., & Kortum, E. (2008). A European framework to address psychosocial hazards. Journal of Occupational Health, 50(3), 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesener, T., Gusy, B., & Wolter, C. (2019). The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work & Stress, 33(1), 76–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford Press. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-17205-000 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Little, T. D., Preacher, K. J., Selig, J. P., & Card, N. A. (2007). New developments in latent variable panel analyses of longitudinal data. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(4), 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D., Rioux, C., Odejimi, O. A., & Stickley, Z. L. (2022). Parceling in structural equation modeling: A comprehensive introduction for developmental scientists. Elements in Research Methods for Developmental Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdtke, O., & Robitzsch, A. (2022). A comparison of different approaches for estimating cross-lagged effects from a causal inference perspective. Structural Equation Modeling, 29(6), 888–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, A., Blanc, M. E., & Beauregard, N. (2018). Do age and gender contribute to workers’ burnout symptoms? Occupational Medicine, 68(6), 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, B., Weigelt, O., Hergert, J., Gurt, J., & Gelléri, P. (2017). The use of snowball sampling for multi source organizational research: Some cause for concern. Personnel Psychology, 70(3), 635–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikangas, A., Bakker, A. B., Aunola, K., & Demerouti, E. (2010). Job resources and flow at work: Modelling the relationship via latent growth curve and mixture model methodology. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2008). The relationship of age to ten dimensions of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 392–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, K., & Christensen, M. (2021). Positive participatory organizational interventions: A multilevel approach for creating healthy workplaces. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 696245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, K., Nielsen, M. B., Ogbonnaya, C., Känsälä, M., Saari, E., & Isaksson, K. (2017). Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress, 31(2), 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce-Jones, J. (2010). Happiness at work: Maximizing your psychological capital for success. In Happiness at work: Maximizing your psychological capital for success. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvanova, R. K., & Muros, J. P. (2010). Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redelinghuys, K., Rothmann, S., & Botha, E. (2019). Flourishing-at-work: The role of positive organizational practices. Psychological Reports, 122(2), 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K. (2014). A reciprocal interplay between psychosocial job stressors and worker well-being? A systematic review of the “reversed” effect. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 40(5), 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development preamble. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/policy-documents/resolution-adopted-by-the-general (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Vecchio, R. P., Justin, J. E., & Pearce, C. L. (2010). Empowering leadership: An examination of mediating mechanisms within a hierarchical structure. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(3), 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A. R., Shanine, K. K., Leon, M. R., & Whitman, M. V. (2014). Student-recruited samples in organizational research: A review, analysis, and guidelines for future research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D. C., & Neto, F. (2013). Workplace well-being, gender and age: Examining the “double jeopardy” effect. Social Indicators Research, 114(3), 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winton, B. G., & Sabol, M. A. (2022). A multi-group analysis of convenience samples: Free, cheap, friendly, and fancy sources. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 25(6), 861–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. A., & Cropanzano, R. (2000). Psychological well-being and job satisfaction as predictors of job performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82(1), 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Liu, D., & Tang, D. S. (2022). Decent work and innovative work behaviour: Mediating roles of work engagement, intrinsic motivation and job self-efficacy. Creativity and Innovation Management, 31(1), 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean (n) | SD (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 44.07 | 13.25 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | (137) | (33.5) |

| Female | (267) | (65.3) |

| Educational level | ||

| Elementary school | (1) | (0.2) |

| High school | (19) | (4.5) |

| High School | (184) | (43.4) |

| Bachelor’s degree | (59) | (13.9) |

| Master’s degree | (126) | (29.7) |

| Second-level master’s degree | (25) | (5.9) |

| Doctorate degree | (10) | (2.4) |

| Work sector | ||

| Manufacturing | (10) | (2.7) |

| Construction | (4) | (1.1) |

| Wholesale trade | (22) | (6) |

| Hospitality | (31) | (8.5) |

| Communication | (9) | (2.5) |

| Financial services | (11) | (3) |

| Business service providers | (15) | (4.1) |

| ICT | (3) | (0.8) |

| Education | (85) | (23.3) |

| Healthcare and social services | (35) | (8.8) |

| Science and technology | (10) | (2.7) |

| Artistic and literary fields | (6) | (1.6) |

| Military service | (25) | (6.8) |

| Other | (102) | (27.9) |

| Seniority | 19.27 | 11.52 |

| Role tenure | 11.57 | 9.68 |

| Years of work in the current team | 7.44 | 7.38 |

| Work contract | ||

| Permanent | (322) | (76.3) |

| Fixed-term | (56) | (13.3) |

| Self-employed | (17) | (4.0) |

| Other | (27) | (6.4) |

| Work hours | ||

| Full-time | (335) | (79.0) |

| Part-time | (89) | (21.0) |

| Work modality | ||

| Office-based | (328) | (81.6) |

| Remote | (4) | (1.0) |

| Hybrid | (70) | (17.4) |

| Mean | SD | Skew | Kurt | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Decent work T1 | 3.57 | 0.72 | −0.29 | 0.08 | 0.79 | ||||||||||

| 2. Decent work T2 | 3.56 | 0.71 | −0.36 | −0.22 | 0.74 *** | 0.82 | |||||||||

| 3. Decent work T3 | 3.61 | 0.74 | −0.23 | −0.25 | 0.66 *** | 0.79 *** | 0.85 | ||||||||

| 4. Flourishing T1 | 4.98 | 0.98 | −0.51 | 0.95 | 0.46 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.90 | |||||||

| 5. Flourishing T2 | 4.94 | 0.99 | −0.28 | 0.99 | 0.50 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.72 *** | 0.91 | ||||||

| 6. Flourishing T3 | 4.92 | 1.08 | −0.34 | 0.51 | 0.36 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.56 *** | 0.67 *** | 0.70 *** | 0.94 | |||||

| 7. Performance T1 | 8.83 | 1.28 | −0.74 | 2.59 | 0.22 *** | 0.21 ** | 0.28 *** | 0.38 *** | 28 *** | 0.25 *** | - | ||||

| 8. Performance T2 | 8.82 | 1.34 | −1.45 | 5.69 | 0.29 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.54 *** | - | |||

| 9. Performance T3 | 8.83 | 1.36 | −1.69 | 8.33 | 0.16 * | 0.24 ** | 0.35 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.55 *** | 0.60 *** | - | ||

| 10. Gender (0=m;1=f) | - | - | - | - | −0.11 * | −0.12 * | −0.07 | −0.13 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.10 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.02 | − | |

| 11. Age | 44.07 | 13.25 | −0.23 | −1.14 | 0.14 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.13 * | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.13 * | 0.02 | −0.11 * | − |

| YBχ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (95% CIs) | SRMR | Comparison | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1. Stability | 589.89 *** | 310 | 0.949 | 0.943 | 0.046 (0.040–0.052, p = 0.874) | 0.093 | - | - | - | - |

| M2. Normal causation | 547.52 *** | 306 | 0.956 | 0.950 | 0.043 (0.037–0.049, p = 0.977) | 0.063 | M2 vs. M1 | −0.007 | −0.003 | −0.030 |

| M3. Reversed causation | 577.66 *** | 306 | 0.955 | 0.944 | 0.044 (0.040–0.051, p = 0.894) | 0.063 | M3 vs. M2 | −0.006 | −0.002 | −0.030 |

| M4. Reciprocal causation | 536.03 *** | 302 | 0.958 | 0.951 | 0.043 (0.037–0.048, p = 0.981) | 0.059 | M4 vs. M1 | −0.009 | −0.003 | −0.034 |

| M4 vs. M2 | −0.002 | 0.000 | −0.004 | |||||||

| M4 vs. M3 | −0.003 | −0.001 | −0.004 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marzocchi, I.; Fusco, L.; Olivo, I.; Isolani, S.; Spinella, F.; Ghezzi, V.; Ghelli, M.; Ronchetti, M.; Persechino, B.; Barbaranelli, C. From Rights to Responsibilities at Work: The Longitudinal Interplay of Decent Work, Flourishing, and Job Performance Across Italian Employees. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040499

Marzocchi I, Fusco L, Olivo I, Isolani S, Spinella F, Ghezzi V, Ghelli M, Ronchetti M, Persechino B, Barbaranelli C. From Rights to Responsibilities at Work: The Longitudinal Interplay of Decent Work, Flourishing, and Job Performance Across Italian Employees. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):499. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040499

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarzocchi, Ivan, Luigi Fusco, Ilaria Olivo, Stefano Isolani, Francesca Spinella, Valerio Ghezzi, Monica Ghelli, Matteo Ronchetti, Benedetta Persechino, and Claudio Barbaranelli. 2025. "From Rights to Responsibilities at Work: The Longitudinal Interplay of Decent Work, Flourishing, and Job Performance Across Italian Employees" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040499

APA StyleMarzocchi, I., Fusco, L., Olivo, I., Isolani, S., Spinella, F., Ghezzi, V., Ghelli, M., Ronchetti, M., Persechino, B., & Barbaranelli, C. (2025). From Rights to Responsibilities at Work: The Longitudinal Interplay of Decent Work, Flourishing, and Job Performance Across Italian Employees. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040499