Unwilling or Unable? The Impact of Role Clarity and Job Competence on Frontline Employees’ Taking Charge Behaviors in Hospitality Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

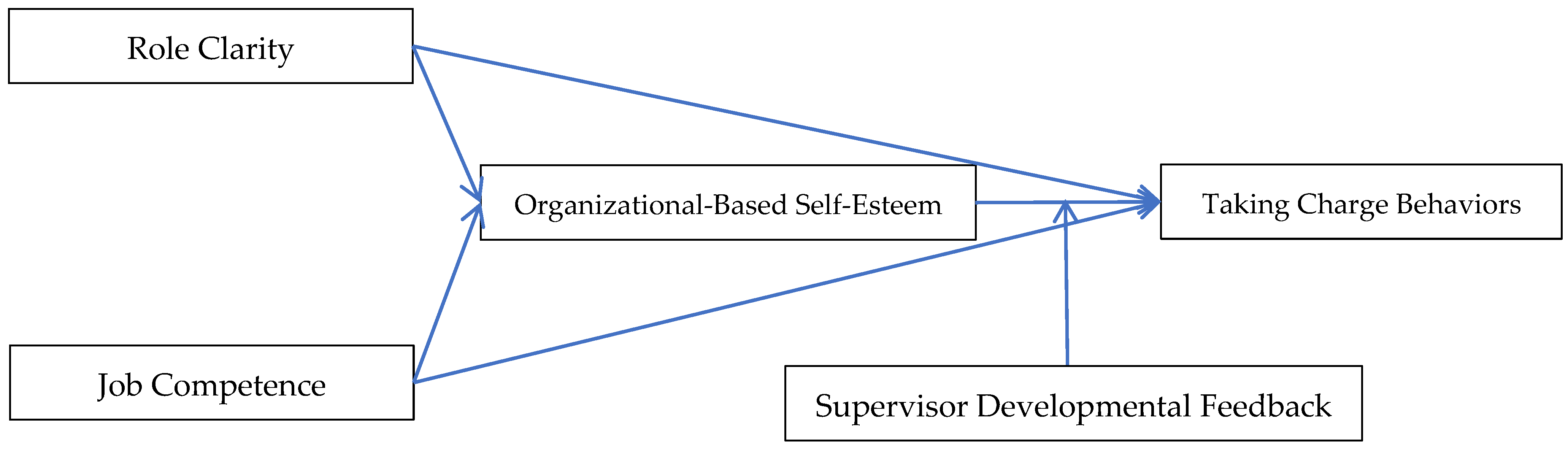

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Employees’ Taking Charge Behaviors

2.2. Role Clarity

2.3. Job Competence

2.4. Organization-Based Self-Esteem

2.5. Supervisor Developmental Feedback

2.6. The Current Study

3. Method

3.1. Procedure

3.2. Ethics

3.3. Participants

3.4. Measurement

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Correlation Analysis

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RC | Role Clarity |

| JC | Job Competence |

| OBSE | Organization-Based Self-Esteem |

| TCB | Taking Charge Behavior |

| SDF | Supervisor Developmental Feedback. |

References

- Abraham, K. M., Erickson, P. S., Sata, M. J., & Lewis, S. B. (2022). Job satisfaction and burnout among peer support specialists: The contributions of supervisory mentorship, recovery-oriented workplaces, and role clarity. Advances in Mental Health, 20(1), 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J., Zahid, S., Wahid, F. F., & Ali, S. (2021). Impact of role conflict and role ambiguity on job satisfaction the mediating effect of job stress and moderating effect of Islamic work ethics. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 6(4), 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J., Brenninkmeijer, V., Huibers, M., & Blonk, R. W. (2013). Competencies for the contemporary career: Development and preliminary validation of the career competencies questionnaire. Journal of Career Development, 40(3), 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almustafa, A., Mustafa, M. J., & Butt, M. M. (2025). Does investment in employee development encourage proactive behaviors among hospitality staff? A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 24(1), 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriansyah, M. A., Sudiro, A., & Juwita, H. A. J. (2023). Employee performance as mediated by organisational commitment between transactional leadership and role ambiguity. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science, 12(5), 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, H. (2020). Supervisor feedback and innovative work behavior: The mediating roles of trust in supervisor and affective commitment. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 559160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G. C., Woznyj, H. M., & Mansfield, C. A. (2023). Where is “behavior” in organizational behavior? A call for a revolution in leadership research and beyond. The Leadership Quarterly, 34(6), 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernuzzi, C., Sommovigo, V., Maffoni, M., Setti, I., & Argentero, P. (2023). A mixedmethod study on the bright side of organizational change: Role clarity and supervisor support as resources for employees’ resilience. Journal of Change Management, 23(2), 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, K. C. (2024). A Self-regulatory model of entrepreneurs’ variability in decision-making and taking charge behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N. A., Eschleman, K. J., Wang, Q., Kirkendall, C., & Alarcon, G. (2010). A meta-analysis of the predictors and consequences of organization-based selfesteem. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C. J., Adams, G. S., & Monin, B. (2013). When cheating would make you a cheater: Implicating the self prevents unethical behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(4), 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, S. Y., Yang, A. J. F., & Huang, Y. C. (2021). Hotel frontline service employees’ creativity and customer-oriented boundary-spanning behaviors: The effects of role stress and proactive personality. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, C., Forney, A., & Pearl, J. (2024). A crash course in good and bad controls. Sociological Methods & Research, 53(3), 1071–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desa, N., & Ding, J. (2016). Effects of organizational learning culture and developmental feedback on engineers’ career satisfaction in the manufacturing organizations in malaysia. International Review of Management and Business Research, 5(3), 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dhir, S., Tandon, A., & Dutta, T. (2024). Spotlighting employee-organization relationships: The role of organizational respect and psychological capital in organizational performance through organizational-based self-esteem and perceived organizational membership. Current Psychology, 43(22), 19964–19975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokoohaki, R., Rambod, M., Pasyar, N., Parviniannasab, A. M., Shaygan, M., Kalyani, M. N., Mohebbi, Z., & Jaberi, A. (2024). Comparison of professional competency and anxiety of nursing students trained based on two internship models: A comparative study. BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysvik, A., Kuvaas, B., & Buch, R. (2016). Perceived investment in employee development and taking charge. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(1), 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhli, A., Komardi, D., & Putra, R. (2022). Commitment, Competence, leadership style, and work culture on job satisfaction and employee performance at the office of the ministry of religion, Kampar district. Journal of Applied Business and Technology, 3(1), 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C., Ran, Y., Huan, Z., & Xiaoyan, Z. (2025). The mediating role of decent work perception in role clarity and job embeddedness among Chinese nurses: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 24(1), 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghlichlee, B., & Bayat, F. (2021). Frontline employees’ engagement and business performance: The mediating role of customer-oriented behaviors. Management Research Review, 44(2), 290–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J. R., & Hood, E. (2021). Organization-based self-esteem and work-life outcomes. Personnel Review, 50(1), 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M., Parker, S., & Collins, C. (2009). Getting credit for proactive behavior: Supervisor reactions depend on what you value and how you feel. Personnel Psychology, 62(1), 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S., & Yang, Y. (2024). Politics matter: Public leadership and taking charge behavior in the public sector. Public Policy and Administration. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Xiong, G., Zhang, Z., Tao, J., & Deng, C. (2020). Effects of supervisor’s developmental feedback on employee loyalty: A moderated mediation model. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 48(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, F. A., Hamstra, M. R., Escribano, P. I., & Fu, X. (2024). Employees’ attitudinal reactions to supervisors’ weekly taking charge behavior: The moderating role of employees’ proactive personality. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 39(8), 993–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homberg, F., Vogel, R., & Weiherl, J. (2019). Public service motivation and continuous organizational change: Taking charge behaviour at police services. Public Administration, 97, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C., Lee, C., & Niu, X. (2010). The moderating effects of polychronicity and achievement striving on the relationship between task variety and organization-based self-esteem of mid-level managers in china. Human Relations, 63(9), 1395–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M., Rhee, S.-Y., Lee, E. J., & Park, H. (2022). Corporate social responsibility perceptions and sustainable safety behaviors among frontline employees: The mediating roles of organization-based self-esteem and work engagement. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(1), 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H., Park, M., & Song, J. H. (2024). Career competencies: An integrated review of the literature. European Journal of Training and Development, 48(7/8), 805–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, T., Brewster, C., & Suutari, V. (2008). Career capital during international work experiences: Contrasting self-initiated expatriate experiences and assigned expatriation. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(6), 979–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D. M., Quinn, R. P., Snoek, J. D., & Rosenthal, R. A. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Kett, P. M., Bekemeier, B., Patterson, D. G., & Schaffer, K. (2023). Competencies, training needs, and turnover among rural compared with urban local public health practitioners: 2021 public health workforce interests and needs survey. American Journal of Public Health, 113(6), 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilroy, J., Dundon, T., & Townsend, K. (2023). Embedding reciprocity in human resource management: A social exchange theory of the role of frontline managers. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(2), 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Park, Y., Kim, B., & Lee, C. K. (2024). Impact of perceptions of ESG on organization-based self-esteem, commitment, and intention to stay. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 41(1), 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. L., Yun, S., & Cheong, M. (2023). Empowering and directive leadership and taking charge: A moderating role of employee intrinsic motivation. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 38(6), 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-Y., Liu, Z., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2015). Leader–member exchange and job performance: The effects of taking charge and organizational tenure. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(2), 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2020). Becoming a behavioral science researcher: A guide to producing research that matters (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L., Ding, H., Liu, S., Yu, S., & Qin, C. (2024). How and when does employees’ learning goal orientation contribute to taking charge behaviour? The roles of empowering leadership and work-related flow. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 34(5), 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., Liu, Z., & Jin, Y. (2022). Evaluation of employee empowerment on taking charge behaviour: An application of perceived organizational support as a moderator. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D., Lee, J., & Kim, S. Y. (2024). Paving the way for interpersonal collaboration in telework: The moderating role of organizational goal clarity in the public workplace. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 44(4), 768–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-L., Sun, F., & Li, M. (2019). Sustainable human resource management nurtures changeoriented employees: Relationship between high-commitment work systems and employees’ taking charge behaviors. Sustainability, 11(13), 3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., & Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Fang, Y., Hu, L., Chen, N., Li, X., & Cai, Y. (2024). Inclusive leadership and employee workplace well-being: The role of vigor and supervisor developmental feedback. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y., Wu, C. H., Kwan, H. K., Lee, C., & Deng, H. (2023). Why and when job insecurity hinders employees’ taking charge behavior: The role of flexibility and work-based self-esteem. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 44(3), 853–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M., Paul, J., Khan, T. I., Abukhait, R., & Hussain, D. (2025). Customer evangelists: Elevating hospitality through digital competence, brand image, and corporate social responsibility. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 126, 104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D. J., Kamdar, D., Morrison, E. W., & Turban, D. B. (2007). Disentangling role perceptions: How perceived role breadth, discretion, instrumentality, and efficacy relate to helping and taking charge. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1200–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H., Kamdar, D., Mayer, D. M., & Takeuchi, R. (2008). Me or we? the role of personality and justice as other-centered antecedents to innovative citizenship behaviors within organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. W., & Phelps, C. C. (1999). Taking charge at work: Extrarole efforts to initiate workplace change. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4), 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. W., Wheeler-Smith, S. L., & Kamdar, D. (2011). Speaking up in groups: A cross-level study of group voice climate and voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussner, T., Strobl, A., Veider, V., & Matzler, K. (2017). The effect of work ethic on employees’ individual innovation behavior. Creativity and Innovation Management, 26(4), 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J. L., & Gardner, D. G. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. Journal of Management, 30(5), 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J. L., Gardner, D. G., Cummings, L. L., & Dunham, R. B. (1989). Organization-based selfesteem: Construct definition, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 32(3), 622–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PJ, S., Singh, K., Kokkranikal, J., Bharadwaj, R., Rai, S., & Antony, J. (2023). Service quality and customer satisfaction in hospitality, leisure, sport and tourism: An assessment of research in web of science. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 24(1), 24–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presti, A. L., Capone, V., Aversano, A., & Akkermans, J. (2022). Career competencies and career success: On the roles of employability activities and academic satisfaction during the school-to-work transition. Journal of Career Development, 49(1), 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, J. R., House, R. J., & Lirtzman, S. I. (1970). Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 15(2), 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satwika, P. A., Suhariadi, F., & Samian. (2025). Exploring proactive work behavior: A scope review of research trends and theories. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2465904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibel, O., Osiyevskyy, O., & Radnejad, A. B. (2025). Strategic entrepreneurship in VUCA environment: The competing forces of outcome variability. Management Research Review, 48(2), 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibunruang, H., & Kawai, N. (2024). The proactive nature of employee voice: The facilitating role of supervisor developmental feedback. Journal of Management & Organization, 30(4), 1100–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, E., Egeland, T., Sandvik, A. M., & Schei, V. (2022). Encouraging or expecting flexibility? How small business leaders’ mastery goal orientation influences employee flexibility through different work climate perceptions. Human Relations, 75(12), 2246–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staller, K. M. (2021). Big enough? Sampling in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Social Work, 20(4), 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X., Gao, P., He, Y., & Zhu, X. (2019). Effect of leaders’ implicit followership prototypes on employees’ internal and external marketability. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 47(12), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, E., Kim, S., Lee, S. M., Yang, J. J., & Lee, Y. K. (2020). The effect of leader competencies on knowledge sharing and job performance: Social capital theory. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 42, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, W. L., Abdin, E., P. V., A., Siva Kumar, F. D., Roystonn, K., Wang, P., Shafie, S., Chang, S., Jeyagurunathan, A., Vaingankar, J. A., Sum, C. F., Lee, E. S., van Dam, R. M., & Subramaniam, M. (2023). Measuring social desirability bias in a multi-ethnic cohort sample: Its relationship with self-reported physical activity, dietary habits, and factor structure. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udahemuka, F. F., Walumbwa, F. O., & Ngoye, B. (2024). Spiritual leadership and intrinsic motivation: The roles of supervisors’ developmental feedback and supportive organizational culture. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 21(4), 481–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul-Hassan, F. S., Ikramullah, M., Khan, H., & Shah, H. A. (2021). Linking role clarity and organizational commitment of social workers through job involvement and job satisfaction: A test of serial multiple mediation model. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 45(4), 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Jiao, H., & Song, J. (2023). Wear glasses for supervisors to discover the beauty of subordinates: Supervisor developmental feedback and organizational ambidexterity. Journal of Business Research, 158, 113650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Zhang, J., He, J., & Bi, Y. (2022). Paradoxical leadership and employee innovation: Organization-based self-esteem and harmonious passion as sequential mediators. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 50(7), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A. J., Loi, R., & Chow, C. W. C. (2022). Why and when proactive employees take charge at work: The role of servant leadership and prosocial motivation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 31(1), 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M., & Rangnekar, S. (2015). Service quality from the lenses of role clarity and organizational itizenship behavior. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 189, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z., Dato Mansor, Z., & Choo, W. C. (2023). Antecedents of proactive customer service performance in hospitality: A meta-analysis. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 32(4), 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. L., Wu, C., Yan, J. R., Liu, J. H., Wang, P., Hu, M. Y., Liu, F., Qu, H. M., & Lang, H. J. (2023). The relationship between role ambiguity, emotional exhaustion and work alienation among chinese nurses two years after COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Bmc Psychiatry, 23(1), 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X., Diaz, I., Zheng, X., & Tang, N. (2017). From deep-level similarity to taking charge: The moderating role of face consciousness and managerial competency of inclusion. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(1), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. (2003). When the presence of creative coworkers is related to creativity: Role of supervisor close monitoring, developmental feedback, and creative personality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., Liu, Y., Ren, L., Tian, F., & Zhang, X. (2024). How does perceived organizational support promote expatriates’ taking charge behavior: The roles of psychological ownership and the subsidiary support climate. Current Psychology, 44, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | Median | Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role Clarity | 3.749 | 0.579 | 3.800 | 2.200–5.000 |

| Job Competence | 3.253 | 0.859 | 3.333 | 1.000–5.000 |

| Organization-Based Self-Esteem | 3.445 | 0.737 | 3.600 | 1.000–5.000 |

| Taking Charge Behavior | 3.348 | 0.793 | 3.300 | 1.440–5.000 |

| Developmental Feedback | 3.679 | 0.575 | 3.667 | 1.890–5.000 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Lobby | ||||||||

| 2. Catering | −0.315 ** | |||||||

| 3. Room | −0.233 ** | −0.365 ** | ||||||

| 4. Clubhouse | −0.220 ** | −0.343 ** | −0.255 ** | |||||

| 5. RC | −0.089 | 0.037 | 0.113 * | −0.051 | ||||

| 6. JC | −0.194 ** | 0.114 * | 0.099 | 0.004 | 0.405 ** | |||

| 7. OBSE | −0.153 ** | 0.043 | 0.110 * | −0.001 | 0.468 ** | 0.582 ** | ||

| 8. TCB | −0.098 | 0.032 | 0.128 * | −0.011 | 0.365 ** | 0.460 ** | 0.401 ** | |

| 9. SDF | −0.152 ** | 0.039 | 0.174 ** | −0.016 | 0.283 ** | 0.329 ** | 0.297 ** | 0.223 ** |

| DV: TCB | DV: OBSE | DV: TCB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | |

| IV | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β |

| Lobby | 0.023 | 0.035 | 0.056 | −0.083 | −0.057 | 0.059 | 0.067 | 0.061 | 0.075 |

| Catering | 0.153 | 0.127 | 0.068 | 0.031 | −0.043 | 0.118 | 0.077 | 0.114 | 0.123 |

| Room | 0.215 * | 0.169 * | 0.136 | −0.1058 | 0.17 | 0.153 * | 0.133 * | 0.149 | 0.150 |

| Clubhouse | 0.101 | 0.101 | 0.058 | 0.030 | −0.026 | 0.093 | 0.063 | 0.081 | 0.100 |

| RC | 0.350 *** | 0.454 *** | 0.220 *** | ||||||

| JC | 0.450 *** | 0.574 *** | 0.336 *** | ||||||

| OBSE | 0.285 *** | 0.198 ** | 0.360 *** | 0.352 *** | |||||

| SDF | 0.096 | 0.128 * | |||||||

| OBSE × SDF | 0.202 *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.029 | 0.149 | 0.221 | 0.233 | 0.343 | 0.211 | 0.246 | 0.182 | 0.221 |

| F | 6.504 | 12.128 *** | 19.597 *** | 20.995 *** | 36.062 *** | 15.418 *** | 18.798 *** | 12.783 *** | 13.974 *** |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | Est./S.E. | LLCI | ULCI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path 1 | Direct Effect | RC--TCB | 0.321 | 0.069 | 4.629 | 0.185 | 0.450 |

| Indirect Effect | RC--OBSE-TCB | 0.142 | 0.039 | 3.638 | 0.072 | 0.230 | |

| Path 2 | Direct Effect | JC--TCB | 0.335 | 0.071 | 4.690 | 0.200 | 0.484 |

| Indirect Effect | JC--OBSE-TCB | 0.104 | 0.039 | 2.644 | 0.029 | 0.184 |

| Mediating Effect: RC → OBSE → TCB | ||||||

| Moderator SDF | Effect | Coefficient | 95%CI | |||

| S.E. | Est./S.E. | p | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| High Level | 0.244 | 0.050 | 4.46212 | 0.000 | 0.157 | 0.336 |

| Low Level | 0.054 | 0.041 | 1.315 | 0.189 | −0.020 | 0.146 |

| INDD | 0.190 | 0.055 | 3.428 | 0.001 | 0.091 | 0.309 |

| Mediating Effect: JC → OBSE → TCB | ||||||

| Moderator SDF | Effect | Coefficient | 95%CI | |||

| S.E. | Est./S.E. | p | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| High Level | 0.191 | 0.038 | 4.953 | 0.000 | 0.121 | 0.271 |

| Low Level | 0.017 | 0.038 | 0.450 | 0.653 | −0.051 | 0.100 |

| INDD | 0.174 | 0.042 | 4.099 | 0.000 | 0.096 | 0.263 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lan, M.; Hu, Z.; Nie, T. Unwilling or Unable? The Impact of Role Clarity and Job Competence on Frontline Employees’ Taking Charge Behaviors in Hospitality Industry. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040526

Lan M, Hu Z, Nie T. Unwilling or Unable? The Impact of Role Clarity and Job Competence on Frontline Employees’ Taking Charge Behaviors in Hospitality Industry. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):526. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040526

Chicago/Turabian StyleLan, Mengfen, Zhehua Hu, and Ting Nie. 2025. "Unwilling or Unable? The Impact of Role Clarity and Job Competence on Frontline Employees’ Taking Charge Behaviors in Hospitality Industry" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040526

APA StyleLan, M., Hu, Z., & Nie, T. (2025). Unwilling or Unable? The Impact of Role Clarity and Job Competence on Frontline Employees’ Taking Charge Behaviors in Hospitality Industry. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 526. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040526