Perceived Social Support from Parents, Teachers, and Friends as Predictors of Test Anxiety in Chinese Final-Year High School Students: The Mediating Role of Academic Buoyancy

Abstract

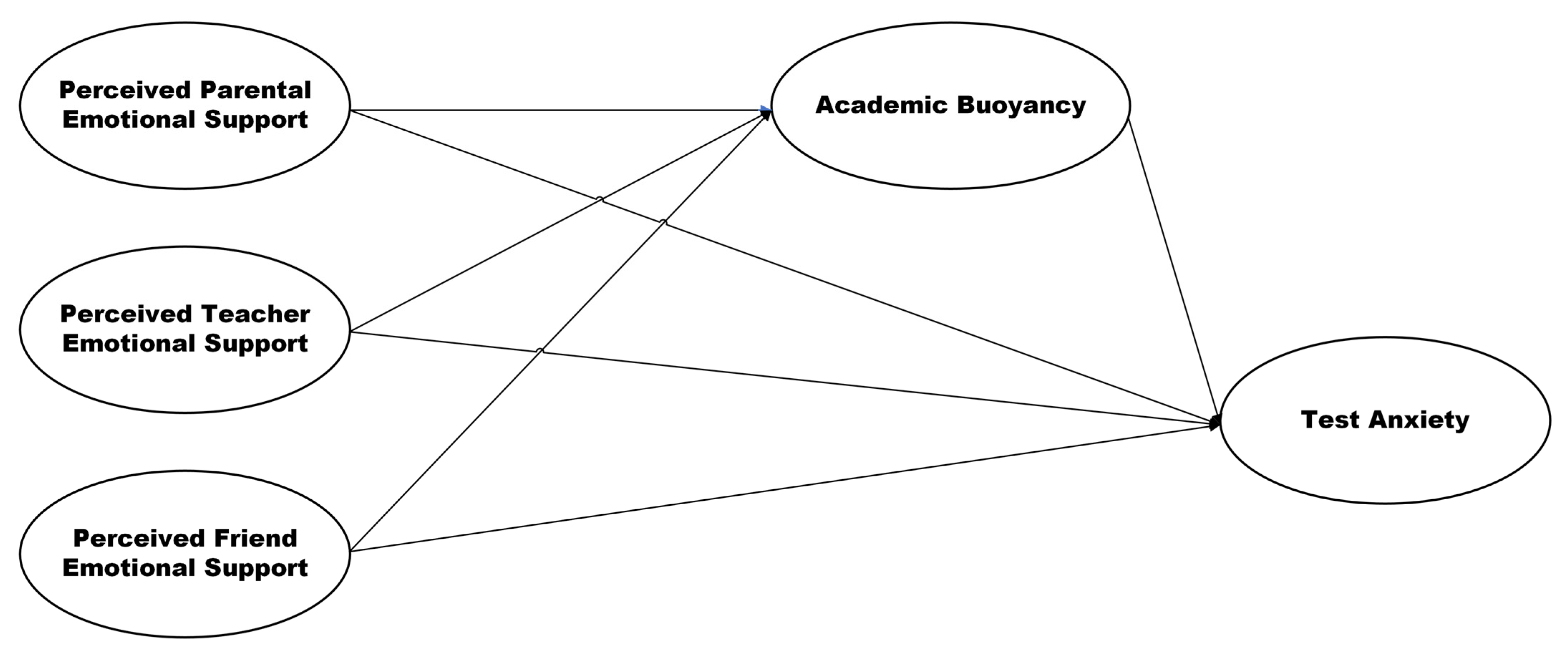

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Perceived Emotional Support Scale

2.2.2. Academic Buoyancy Scale

2.2.3. Brief FRIEDBEN Test Anxiety Scale

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis and Correlation Analysis

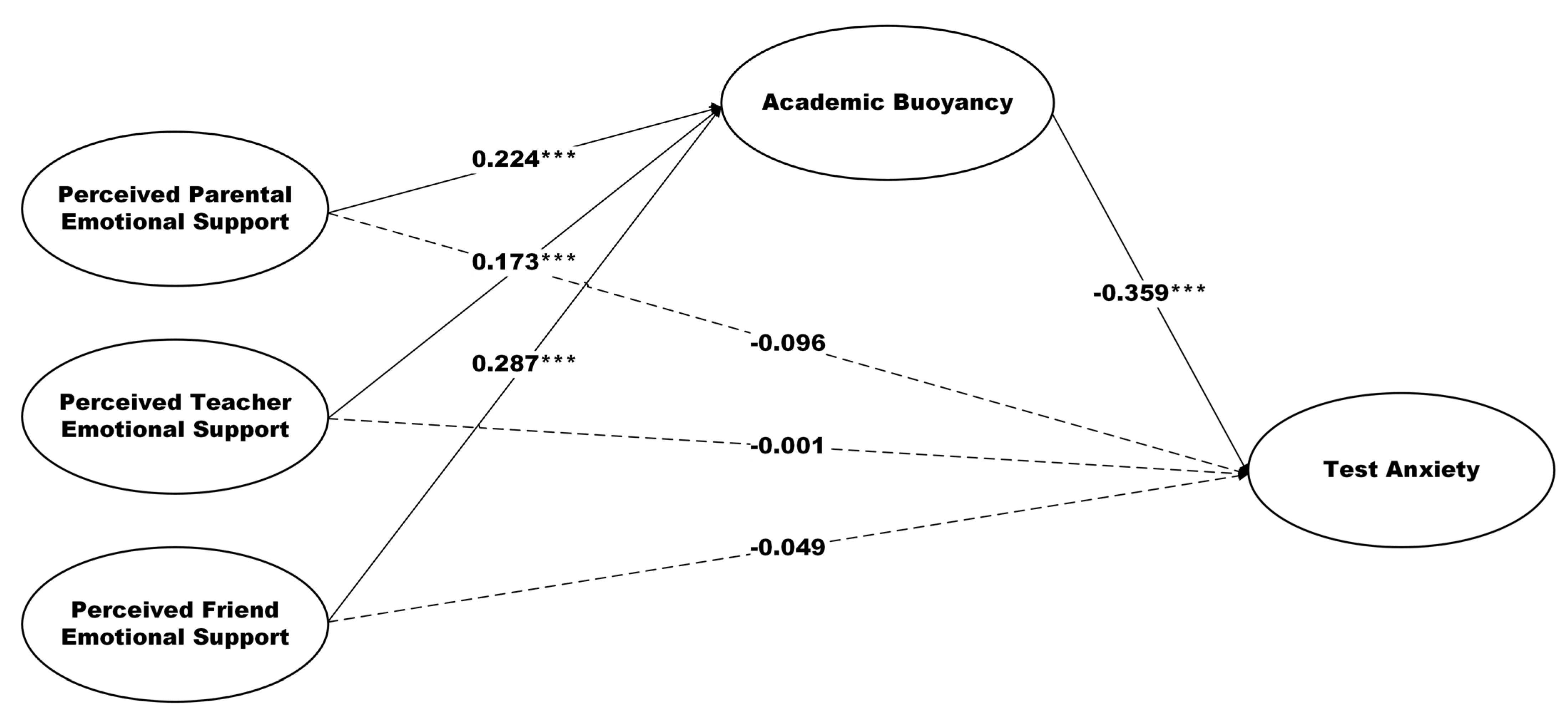

3.2. Results of Structural Equation Modeling

3.3. The Mediating Effect of Academic Buoyancy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, W., Minnaert, A., van der Werf, G., & Kuyper, H. (2010). Perceived social support and early adolescents’ achievement: The mediational roles of motivational beliefs and emotions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(1), 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramnejad, H., Yarahmadi, Y., Ahmadian, H., & Akbari, M. (2021). Developing of school satisfaction model based on perception of classroom environment and perception of teacher support mediated by academic buoyancy and academic engagement. Research in School and Virtual Learning, 8(3), 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhorst, C. L., Sumter, S. R., & Westenberg, P. M. (2010). Social support from parents, friends, classmates, and teachers in children and adolescents aged 9 to 18 years: Who is perceived as most supportive? Social Development, 19(2), 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (2015). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Ravenio Books. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. J.-L. (2005). Relation of academic support from parents, teachers, and peers to HONG KONG adolescents’ academic achievement: The mediating role of academic engagement. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 131(2), 77–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, P. S., Saucier, D. A., & Hafner, E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(6), 624–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, L., He, W., Peng, G., Yin, Y., Chen, T., & Mao, X. (2014). Meta-analysis of the reporting rate of suicide-related behaviors among middle school students in China. Chinese School Hygiene, 35(4), 532–536. [Google Scholar]

- DordiNejad, F. G., Hakimi, H., Ashouri, M., Dehghani, M., Zeinali, Z., Daghighi, M. S., & Bahrami, N. (2011). On the relationship between test anxiety and academic performance. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 3774–3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., Buchanan, C. M., Flanagan, C., Fuligni, A., Midgley, C., & Yee, D. (1991). Control versus autonomy during early adolescence. Journal of Social Issues, 47(4), 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eum, K., & Rice, K. G. (2011). Test anxiety, perfectionism, goal orientation, and academic performance. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 24(2), 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerwing, T. G., Rash, J. A., Gerwing, A. M. A., Bramble, B., & Landine, J. (2015). Perceptions and incidence of test anxiety. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granziera, H., Liem, G. A. D., Chong, W. H., Martin, A. J., Collie, R. J., Bishop, M., & Tynan, L. (2022). The role of teachers’ instrumental and emotional support in students’ academic buoyancy, engagement, and academic skills: A study of high school and elementary school students in different national contexts. Learning and Instruction, 80, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, R., Putwain, D. W., Määttä, S., Ahonen, T., & Kiuru, N. (2020). The role of academic buoyancy and emotions in students’ learning-related expectations and behaviours in primary school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(4), 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, R. (2006). Handbook of univariate and multivariate data analysis and interpretation with SPSS. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, B., & Phromphithakkul, W. (2024). Relationship between perceived social support and university students’ academic engagement in Shanxi, China: The chain mediating effect of academic buoyancy and academic emotion, the moderating effect of proactive personality. Journal of Nakhonratchasima College (Humanities and Social Sciences), 18(1), 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q., & Zhou, R. L. (2019). The development of test anxiety in Chinese students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(1), 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Eslami, Z., & Hu, R.-J. S. (2010). The relationship between teacher and peer support and English-language learners’ anxiety. English Language Teaching, 3(1), 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- In’nami, Y. (2006). The effects of test anxiety on listening test performance. System, 34(3), 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X., Li, P., & Xie, Y. (2024). Longitudinal effect of the parent-child relationship in home quarantine on internalizing and externalizing problems after school reopening for students in boarding high school: A chain mediation model. Psychology in the Schools, 61(6), 2338–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M. (2008). The relationship between personality factors and test anxiety among university students. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 2(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsford-Smith, A. A., Alonzo, D., Beswick, K., Loughland, T., & Roberts, P. (2024). Perceived autonomy support as a predictor of rural students’ academic buoyancy and academic self-efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 142, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R. V., & Morgan, D. W. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W., Zhang, H., Deng, W., Wang, H., Shao, F., & Hu, W. (2021). Academic self-efficacy and test anxiety in high school students: A conditional process model of academic buoyancy and peer support. School Psychology International, 42(6), 616–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, G. S. M., Yeung, K. C., & Wong, D. F. K. (2010). Academic stressors and anxiety in children: The role of paternal support. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(1), 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. J., & Marsh, H. W. (2008). Academic buoyancy: Towards an understanding of students’ everyday academic resilience. Journal of School Psychology, 46(1), 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengelly, R. (2021). An exploration of teacher and educational psychologists’ support for student test-anxiety in the context of a global pandemic [Doctoral thesis, University of Exeter]. Available online: https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10871/127410 (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Rohinsa, M., Djunaidi, A., Cahyadi, S., & Iskandar, T. B. Z. (2020). Effect of parent support on engagement through need satisfaction and academic buoyancy/efecto del apoyo de los padres en la participacion a traves de la satisfaccion de necesidades y la flotabilidad academica. Utopía y Praxis Praxis Latinoamericana, 25(S6), 144–154. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, L., Tang, X., Hietajärvi, L., Salmela-Aro, K., & Fiorilli, C. (2020). Students’ trait emotional intelligence and perceived teacher emotional support in preventing burnout: The moderating role of academic anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., Pyun, Y., Aycock, C., & Coyle, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142(10), 1017–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semmer, N. K., Elfering, A., Jacobshagen, N., Perrot, T., Beehr, T. A., & Boos, N. (2008). The emotional meaning of instrumental social support. International Journal of Stress Management, 15, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J., Bong, M., Lee, K., & Kim, S. (2015). Longitudinal investigation into the role of perceived social support in adolescents’ academic motivation and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, T., & Suldo, S. (2011). Relationships between social support sources and early adolescents’ mental health: The moderating effect of student achievement level. Psychology in the Schools, 48(10), 1016–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. W. (2009). Effects of everyday academic resilience and academic engagement on students’ performance in high school [Master’s thesis, Northeast Normal University]. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CMFD&dbname=CMFD2009&filename=2009178564.nh&uniplatform=NZKPT&v=SvNInmHrhfQ-1nlClbK1UHnJiY331eKuD-uuoPCfm2J2vFJaMDlB4M_1MvJs0KCf (accessed on 16 October 2009).

- Thomas, C. L., & Ozer, O. (2024). A cross-cultural latent profile analysis of university students’ cognitive test anxiety and related cognitive-motivational factors. Psychology in the Schools, 61(6), 2668–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsehay, A., & Kahsay, M. (2020). Relationship of language learning anxiety with teacher and peer support. Bahir Dar Journal of Education, 20(2), 2. [Google Scholar]

- von der Embse, N. P., Kilgus, S. P., Segool, N., & Putwain, D. (2013). Identification and validation of a brief test anxiety screening tool. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 1(4), 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83(3), 877–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K. R. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K. R., Russell, S., & Baker, S. (2016). Emotional support and expectations from parents, teachers, and peers predict adolescent competence at school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuthrich, V. M., Jagiello, T., & Azzi, V. (2020). Academic stress in the final years of school: A systematic literature review. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51(6), 986–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., & Wang, S. (2023). The relationship between exam anxiety, academic performance and peer support among 9th grade students in Shenzhen, China. Curriculum & Innovation, 1(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S., Hiver, P., & Al-Hoorie, A. H. (2018). Academic buoyancy: Exploring learners’ everyday resilience in the language classroom. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40(4), 805–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | PPES | PTES | PFES | AB | TA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPES | 3.95 | 0.89 | 1 | ||||

| PTES | 3.93 | 0.84 | 0.559 ** | 1 | |||

| PFES | 3.67 | 0.91 | 0.535 ** | 0.524 ** | 1 | ||

| AB | 3.44 | 1.01 | 0.379 ** | 0.359 ** | 0.383 ** | 1 | |

| TA | 2.75 | 0.86 | −0.246 ** | −0.204 ** | −0.262 ** | −0.431 ** | 1 |

| Hypothesized Relationship | Beta | S.E. | C.R. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: PPES → TA | −0.096 | 0.049 | −1.959 | 0.050 |

| H2: PTES → TA | −0.001 | 0.042 | −0.014 | 0.989 |

| H3: PFES → TA | −0.049 | 0.044 | −1.119 | 0.263 |

| H4: PPES → AB | 0.224 | 0.047 | 4.801 | *** |

| H5: PTES → AB | 0.173 | 0.044 | 3.924 | *** |

| H6: PFES → AB | 0.287 | 0.052 | 5.564 | *** |

| H7: AB → TA | −0.359 | 0.050 | −7.225 | *** |

| Model/Hypothesized Path | Beta | S.E. | p | 95% Confidence BC CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | UB | ||||

| Total effects | −0.391 | 0.061 | *** | −0.511 | −0.272 |

| Total indirect effects | −0.245 | 0.043 | *** | −0.340 | −0.170 |

| Indp1: PPES → AB → TA | −0.080 | 0.030 | ** | −0.151 | −0.031 |

| Indp2: PTES → AB → TA | −0.062 | 0.024 | ** | −0.116 | −0.022 |

| Indp3: PFES → AB → TA | −0.103 | 0.031 | *** | −0.173 | −0.049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, D.; Ahmad, N.A.; Roslan, S. Perceived Social Support from Parents, Teachers, and Friends as Predictors of Test Anxiety in Chinese Final-Year High School Students: The Mediating Role of Academic Buoyancy. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040449

Li D, Ahmad NA, Roslan S. Perceived Social Support from Parents, Teachers, and Friends as Predictors of Test Anxiety in Chinese Final-Year High School Students: The Mediating Role of Academic Buoyancy. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(4):449. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040449

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Danwei, Nor Aniza Ahmad, and Samsilah Roslan. 2025. "Perceived Social Support from Parents, Teachers, and Friends as Predictors of Test Anxiety in Chinese Final-Year High School Students: The Mediating Role of Academic Buoyancy" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 4: 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040449

APA StyleLi, D., Ahmad, N. A., & Roslan, S. (2025). Perceived Social Support from Parents, Teachers, and Friends as Predictors of Test Anxiety in Chinese Final-Year High School Students: The Mediating Role of Academic Buoyancy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 449. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040449