Master or Escape: Digitization-Oriented Job Demands and Crafting and Withdrawal of Chinese Public Sector Employees

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Job Crafting and Work Withdrawal Behaviors as a Result of Digitization-Oriented Job Demands

2.2. Resource Enrichment Pathways—The Mediating Role of Thriving at Work

2.3. Resource Loss Pathways—The Mediating Role of Workplace Anxiety

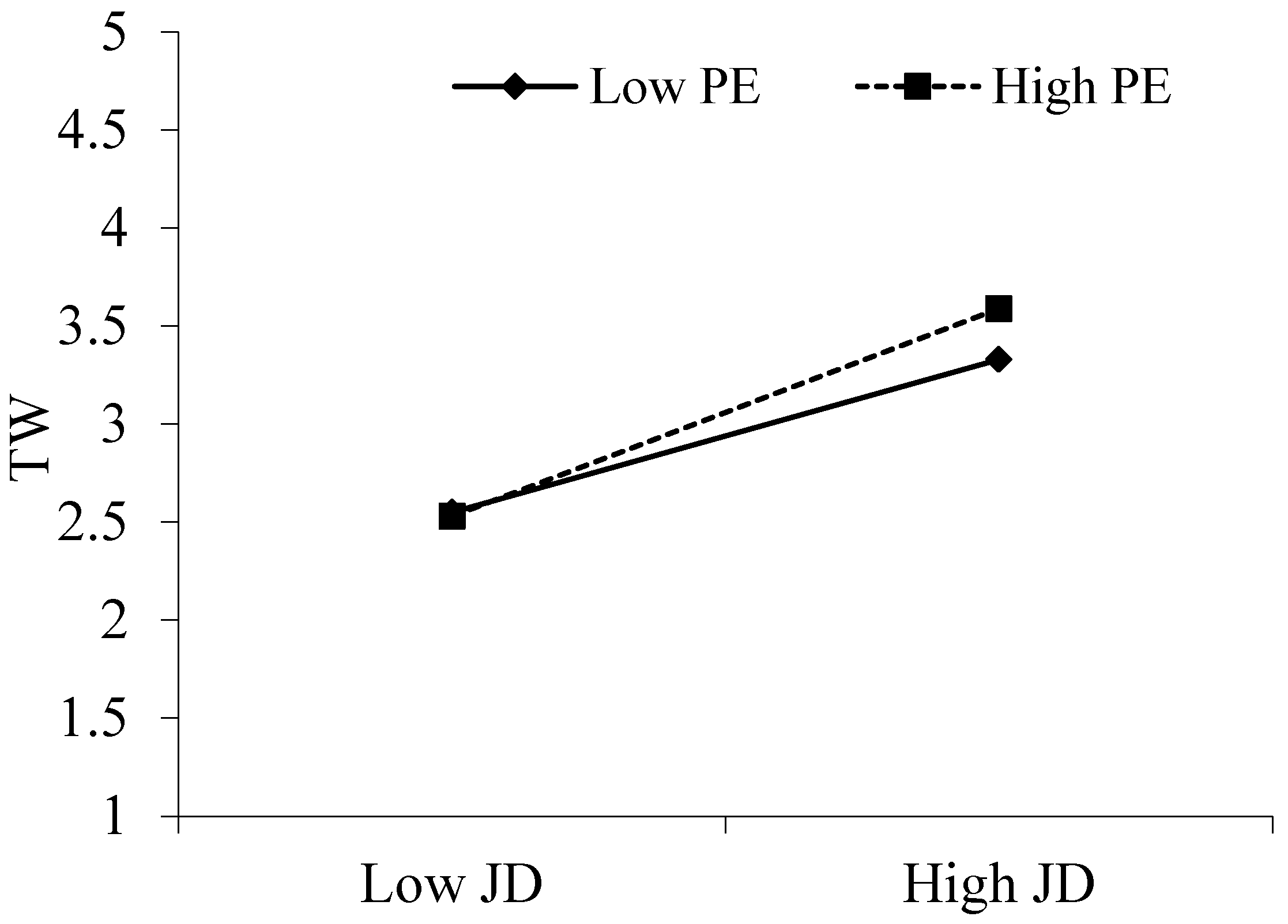

2.4. The Moderating Role of the Regulatory Focus

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Common Method Bias

4.3. Reliability and Validity Analysis and Descriptive Statistics

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguiar-Quintana, T., Nguyen, T. H. H., Araujo-Cabrera, Y., & Sanabria-Díaz, J. M. (2021). Do job insecurity, anxiety and depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic influence hotel employees’ self-rated task performance? The moderating role of employee resilience. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlNuaimi, B. K., Kumar Singh, S., Ren, S., Budhwar, P., & Vorobyev, D. (2022). Mastering digital transformation: The nexus between leadership, agility, and digital strategy. Journal of Business Research, 145, 636–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job demands-resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 34(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, O. (2018). On the future of macroeconomic models. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 34(1–2), 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenninkmeijer, V., Demerouti, E., Le Blanc, P. M., & Hetty Van Emmerik, I. J. (2010). Regulatory focus at work: The moderating role of regulatory focus in the job demands-resources model. Career Development International, 15(7), 708–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetindamar Kozanoglu, D., & Abedin, B. (2021). Understanding the role of employees in digital transformation: Conceptualization of digital literacy of employees as a multi-dimensional organizational affordance. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 34(6), 1649–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., Vrontis, D., & Giovando, G. (2023). Digital workplace and organization performance: Moderating role of digital leadership capability. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 8(1), 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N., Zhao, X., & Wang, L. (2024). The effect of job skill demands under artificial intelligence embeddedness on employees’ job performance: A moderated double-edged sword model. Behavioral Sciences, 14(10), 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2023). Job demands-resources theory in times of crises: New propositions. Organizational Psychology Review, 13(3), 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Gevers, J. M. P. (2015). Job crafting and extra-role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., Li, J., & Xu, Q. (2023). Are you satisfied when your job fits? The perspective of career management. Baltic Journal of Management, 18(5), 563–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feroz, A. K., Zo, H., Eom, J., & Chiravuri, A. (2023). Identifying organizations’ dynamic capabilities for sustainable digital transformation: A mixed methods study. Technology in Society, 73, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R. S., & Förster, J. (2001). The effects of promotion and prevention cues on creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghi, T., Thu, N., Huan, N., & Trung, N. (2022). Human capital, digital transformation, and firm performance of startups in Vietnam. Management, 26(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T., Matt, C., Benlian, A., & Wiesbck, F. (2016). Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Quarterly Executive, 15(2), 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T., Friedman, R. S., Harlow, R. E., Idson, L. C., Ayduk, O. N., & Taylor, A. (2001). Achievement orientations from subjective histories of success: Promotion pride versus prevention pride. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31(1), 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N. S., Axtell, C., Raghuram, S., & Nurmi, N. (2024). Unpacking virtual work’s dual effects on employee well-being: An integrative review and future research agenda. Journal of Management, 50(2), 752–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2012). Conservation of resources and disaster in cultural context: The caravans and passageways for resources. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 75(3), 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Johnson, R. J., Ennis, N., & Jackson, A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 632, Erratum in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y., & Fan, L. (2024). Working with AI: The effect of job stress on hotel employees’ work engagement. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingusci, E., Signore, F., Giancespro, M. L., Manuti, A., Molino, M., Russo, V., Zito, M., & Cortese, C. G. (2021). Workload, techno overload, and behavioral stress during COVID-19 emergency: The role of job crafting in remote workers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 655148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, O. (2000). Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P. D., Smith, M. B., Wallace, J. C., Hill, A. D., & Baron, R. A. (2015). A review of multilevel regulatory focus in organizations. Journal of Management, 41(5), 1501–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H., & Camarena, L. (2024). Street-level bureaucrats & AI interactions in public organizations: An identity based framework. Public Performance & Management Review, 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltiainen, J., & Hakanen, J. J. (2024). Why increase in telework may have affected employee well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic? The role of work and non-work life domains. Current Psychology, 43(13), 12169–12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. N., Shahzad, K., & Khan, N. A. (2024). Fostering accountability through digital transformation: Leadership’s role in enhancing techno-work engagement in public sector. Public Money & Management, 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B., Curtis, C., & Ryan, B. (2021). Examining the impact of artificial intelligence on hotel employees through job insecurity perspectives. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanaj, K., Chang, C.-H., & Johnson, R. E. (2012). Regulatory focus and work-related outcomes: A review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 998–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leana, C., Appelbaum, E., & Shevchuk, I. (2009). Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Academy of Management Journal, 52(6), 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, W. E., & Simpson, D. D. (1992). Employee substance use and on-the-job behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(3), 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmer, K., Jahn, K., Chen, A., & Niehaves, B. (2023). One tool to rule?—A field experimental longitudinal study on the costs and benefits of mobile device usage in public agencies. Government Information Quarterly, 40(3), 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Yang, H., Weng, Q., & Zhu, L. (2023). How different forms of job crafting relate to job satisfaction: The role of person-job fit and age. Current Psychology, 42(13), 11155–11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., Zhang, F., Liu, Y., Liu, S., & Huo, C. (2024). Enabling or burdening?-the double-edged sword impact of digital transformation on employee resilience. Computers in Human Behavior, 157, 108220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, Y., Song, K., & Chu, F. (2024). The two faces of artificial intelligence (AI): Analyzing how AI usage shapes employee behaviors in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 122, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., & Brockner, J. (2015). The interactive effect of positive inequity and regulatory focus on work performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 57, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S., & Tremblay, D.-G. (2020). How can organizations foster job crafting behaviors and thriving at work? Journal of Management & Organization, 27(4), 768–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. M., Trougakos, J. P., & Cheng, B. H. (2016). Are anxious workers less productive workers? It depends on the quality of social exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(2), 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, S., Singh, A., Choudhary, M. H., & Alshammari, A. S. (2024). The mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relationship between digital transformation, innovative work behavior, and organizational financial performance. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nix, G. A., Ryan, R. M., Manly, J. B., & Deci, E. L. (1999). Revitalization through self-regulation: The effects of autonomous and controlled motivation on happiness and vitality. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(3), 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., & Grote, G. (2022). Automation, algorithms, and beyond: Why work design matters more than ever in a digital world. Applied Psychology, 71(4), 1171–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X., Guo, J., & Wu, T.-J. (2025). How ambivalence toward digital–AI transformation affects taking-charge behavior: A threat–rigidity theoretical perspective. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J., Cao, F., Zhang, Y., Cao, Y., Zhang, Y., Zhu, X., & Miao, D. (2021). Reflections on motivation: How regulatory focus influences self-framing and risky decision making. Current Psychology, 40(6), 2927–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C., Spreitzer, G., Gibson, C., & Garnett, F. G. (2012). Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(2), 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, S., Wong, M. S., Chit, M. M., & Mutum, D. S. (2024). The mediating role of occupational stress: A missing link between organisational intelligence traits and digital government service quality. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 41(2), 532–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S., Xu, Y., & Hussain, S. (2018). Understanding employee innovative behavior and thriving at work: A Chinese perspective. Administrative Sciences, 8(3), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosse, J. G., & Hulin, C. L. (1985). Adaptation to work: An analysis of employee health, withdrawal, and change. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36(3), 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacramento, C. A., Fay, D., & West, M. A. (2013). Workplace duties or opportunities? Challenge stressors, regulatory focus, and creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 121(2), 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Reyes, J., Acosta-Prado, J. C., & Sanchís-Pedregosa, C. (2019). Relationship amongst technology use, work overload, and psychological detachment from work. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(23), 4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G., Sutcliffe, K., Dutton, J., Sonenshein, S., & Grant, A. M. (2005). A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organization Science, 16(5), 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P. M., Koopman, J., Mai, K. M., De Cremer, D., Zhang, J. H., Reynders, P., Ng, C. T. S., & Chen, I.-H. (2023). No person is an island: Unpacking the work and after-work consequences of interacting with artificial intelligence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(11), 1766–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygungil-Erdogan, S., Şahin, Y., Sökmen-Alaca, A. İ., Oktaysoy, O., Altıntaş, M., & Topçuoğlu, V. (2025). Assessing the effect of artificial intelligence anxiety on turnover intention: The mediating role of quiet quitting in turkish small and medium enterprises. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P. C., Broekhuizen, T., Bart, Y., Bhattacharya, A., Qi Dong, J., Fabian, N., & Haenlein, M. (2021). Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. (2019). Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 28(2), 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J. C., Johnson, P. D., & Frazier, M. L. (2009). An examination of the factorial, construct, and predictive validity and utility of the regulatory focus at work scale. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(6), 805–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Gong, X., & Liu, Y. (2022). Research on the influence mechanism of employees’ innovation behavior in the context of digital transformation. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1090961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-J., Liang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2024). The buffering role of workplace mindfulness: How job insecurity of human-artificial intelligence collaboration impacts employees’ work–life-related outcomes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 39(6), 1395–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-J., Zhang, R.-X., & Zhang, Z. (2025). Navigating the human-artificial intelligence collaboration landscape: Impact on quality of work life and work engagement. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 62, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Wang, X., & Bell, C. M. (2024). From thriving to task focus: The role of needs-supplies fit and task complexity. Current Psychology, 43(36), 28988–28998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Su, D., Smith, A. P., & Yang, L. (2023). Reducing work withdrawal behaviors when faced with work obstacles: A three-way interaction model. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., & Liu, Y. (2024). Job demands-resources on digital gig platforms and counterproductive work behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1378247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | Code | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1 | 456 | 52.2 |

| Female | 0 | 417 | 47.8 | |

| Education | College and below | 1 | 47 | 5.4 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 2 | 262 | 30.0 | |

| Master’s degree | 3 | 564 | 64.6 | |

| Rank | Section Chief | 1 | 368 | 42.2 |

| Deputy Section | 2 | 291 | 33.3 | |

| Full Section | 3 | 214 | 24.5 |

| Model | Factors | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-factor model | JD; PO; PE; TW; WA; JC; WD | 2451.70 | 901 | 2.72 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| 6-factor model | JD + PO; PE; TW; WA; JC; WD | 11,642.85 | 1112 | 10.47 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| 5-factor model | JD + PO + PE; TW; WA; JC; WD | 15,991.17 | 1117 | 14.32 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| 4-factor model | JD + PO + PE + TW; WA; JC; WD | 23,544.73 | 1121 | 21.00 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| 3-factor model | JD + PO + PE + TW + WA; JC; WD | 26,717.26 | 1124 | 23.77 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.16 |

| 2-factor model | JD + PO + PE + TW + WA + JC; WD | 29,345.35 | 1126 | 26.06 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| 1-factor model | JD + PO + PE + TW + WA + JC + WD | 31,257.59 | 1127 | 27.74 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.19 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (T1) | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Age (T1) | 0.07 * | - | |||||||||

| 3. Education (T1) | 0.05 | 0.14 ** | - | ||||||||

| 4. Rank (T1) | −0.08 * | −0.16 ** | −0.05 | - | |||||||

| 5. JD (T1) | −0.11 ** | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.76 | ||||||

| 6. PO (T1) | −0.16 ** | 0.09 ** | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.35 ** | 0.86 | |||||

| 7. PE (T1) | −0.23 ** | 0.09 ** | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.21 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.80 | ||||

| 8. TW (T2) | −0.10 ** | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.48 ** | 0.33 ** | −0.22 ** | 0.89 | |||

| 9. WA (T2) | −0.12 ** | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.49 ** | −0.37 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.48 ** | 0.89 | ||

| 10. JC (T3) | −0.10 ** | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.44 ** | 0.11 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.33 ** | −0.35 ** | 0.82 | |

| 11. WD (T3) | −0.17 ** | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.56 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.27 ** | −0.52 ** | 0.57 ** | −0.62 ** | 0.73 |

| Mean | 0.48 | 40.53 | 2.59 | 1.82 | 3.83 | 2.57 | 2.55 | 3.64 | 3.64 | 3.73 | 3.83 |

| PE | 0.50 | 9.06 | 0.59 | 0.80 | 0.63 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.70 | 0.51 |

| Cronbach’s α | - | - | - | - | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.89 |

| CR | - | - | - | - | 0.81 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.90 |

| AVE | - | - | - | - | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.53 |

| Variables | TW | JC | WA | WD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| JD | 0.46 *** | 0.03 | 0.41 *** | 0.04 | 0.46 *** | 0.03 | 0.30 *** | 0.02 |

| PO | 0.08 *** | 0.02 | ||||||

| JD × PO | 0.15 *** | 0.03 | ||||||

| PE | 0.06 ** | 0.02 | ||||||

| JD × PE | 0.07 ** | 0.03 | ||||||

| TW | 0.16 *** | 0.04 | ||||||

| WA | 0.30 *** | 0.03 | ||||||

| Gender | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.09 ** | 0.03 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Education | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.05 ** | 0.02 |

| Type | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Moderator: PO | JD→TW→JC | ||

| B | SE | 95% Boot CI | |

| Indirect effect | 0.07 ** | 0.02 | [0.03, 0.15] |

| Direct effect | 0.41 *** | 0.04 | [0.33, 0.48] |

| High (+PE) | 0.10 *** | 0.03 | [0.04, 0.15] |

| Low (−PE) | 0.05 ** | 0.02 | [0.02, 0.09] |

| Index | 0.02 ** | 0.01 | [0.01, 0.04] |

| Moderator: PE | JD→WA→WD | ||

| B | SE | 95% Boot CI | |

| Indirect effect | 0.14 *** | 0.02 | [0.10, 0.20] |

| Direct effect | 0.30 *** | 0.02 | [0.25, 0.34] |

| High (+PE) | 0.16 *** | 0.02 | [0.11, 0.21] |

| Low (−PE) | 0.12 *** | 0.02 | [0.08, 0.16] |

| Index | 0.02 ** | 0.01 | [0.00, 0.04] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, H.; Li, J. Master or Escape: Digitization-Oriented Job Demands and Crafting and Withdrawal of Chinese Public Sector Employees. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030378

Huang H, Li J. Master or Escape: Digitization-Oriented Job Demands and Crafting and Withdrawal of Chinese Public Sector Employees. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):378. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030378

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Huan, and Jiangyu Li. 2025. "Master or Escape: Digitization-Oriented Job Demands and Crafting and Withdrawal of Chinese Public Sector Employees" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030378

APA StyleHuang, H., & Li, J. (2025). Master or Escape: Digitization-Oriented Job Demands and Crafting and Withdrawal of Chinese Public Sector Employees. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 378. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030378