The Impact of Emotion Regulation Strategies on Teachers’ Well-Being and Positive Emotions: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Emotion and Emotion Regulation

2.2. Emotion Regulation Strategies

3. Methodology

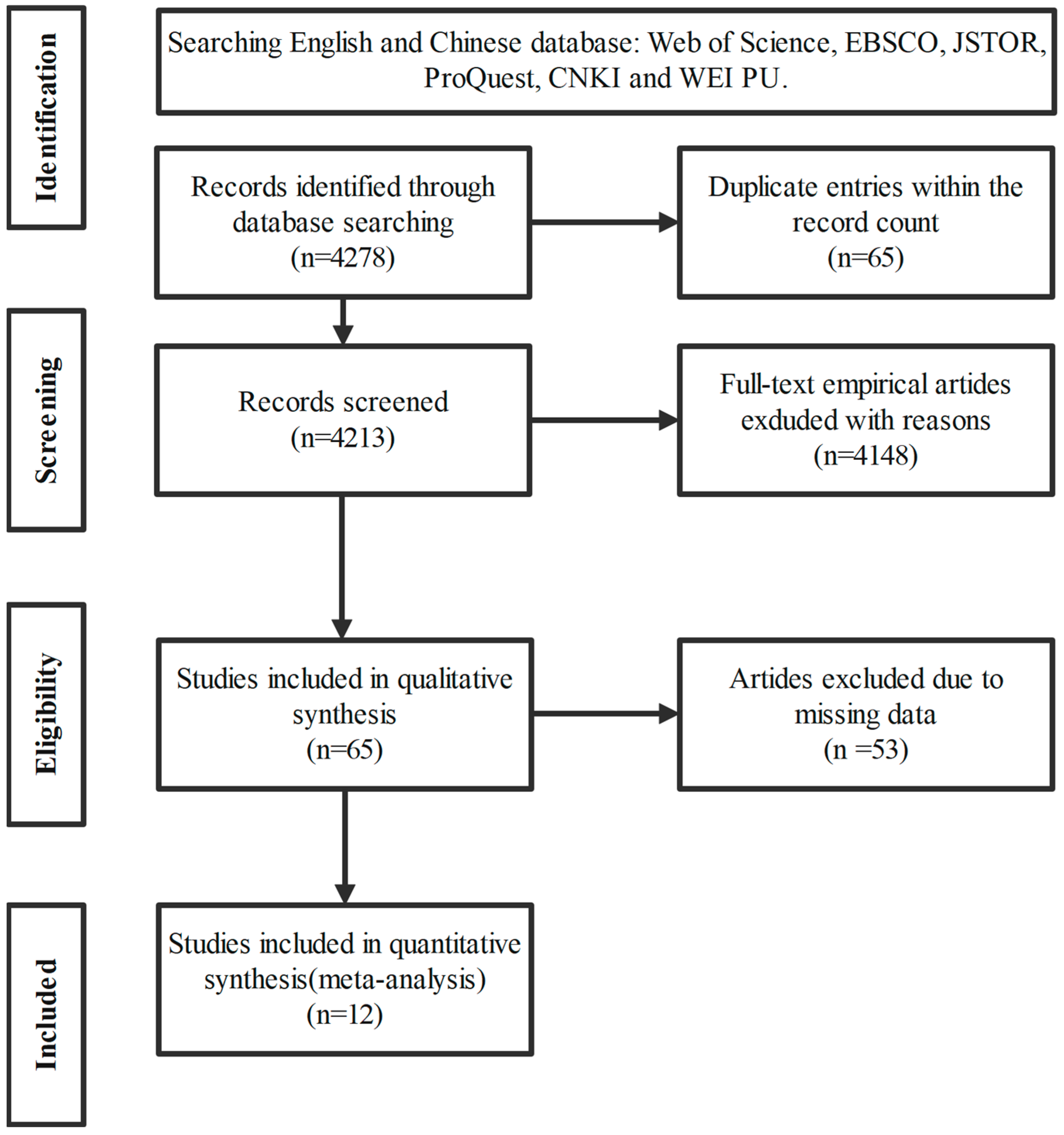

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Studies concentrating on in-service teachers at various stages and in different countries. For instance, “Choose your strategy wisely: Examining the relationships between emotional labor in teaching and teacher efficacy in Hong Kong primary schools” focuses on a sample of 1115 Hong Kong primary school teachers (Yin et al., 2017).

- Studies concentrating on the emotion regulation strategies for regulating teachers’ emotions. For instance, “Adaptation and validation of the teacher emotional labor strategy scale in China”. This article reports the adaptation and validation of the Teacher Emotional Labor Strategy Scale (TELSS) as tested on samples of 633 Beijing teachers and 648 Chongqing teachers in the Chinese mainland (Yin, 2012).

- A quantitative study that assesses teacher emotional regulation by employing reliable, adequate, and effective data sample size. For instance, “Emotional intelligence, emotional labor strategies and satisfaction of secondary teachers in Pakistan”. In this article, there is a sufficient and effective amount of data.

- The included studies are obliged to explore the relationship between emotion regulation strategies and teachers’ emotional regulation. For instance, “Spiral effects of teachers’ emotions and emotion regulation strategies: Evidence from a daily diary study”. In this article, it is expected that positive emotions will promote teachers’ use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies (Lavy & Eshet, 2018).

- The full text of the article is published in English. For instance, “The associations between EFL learners’ L2 class belongingness, emotion regulation strategies, and perceived L2 proficiency in an online learning context”.

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Exclude participants who may not have classroom teaching experience, such as intern teachers, teaching assistants, and school counselors. For instance, in the article “Positive Influence of Cooperative Learning and Emotion Regulation on EFL Learners’ Foreign Language Enjoyment”, the participants are EFL Learners’.

- The study also excluded those emotion regulation strategies that did not focus on the teacher’s emotions, such as “emotional regulation ability”, and also excluded studies that focused on the “teacher’s negative emotions”, as this was exactly opposite to the study’s focus on “positive emotions”. For instance, in “Linking emotion regulation strategies to affective events and negative emotions at work” the main content of the article is how to use emotion regulation strategies to alleviate teachers’ negative emotions.

- Exclude studies with incomplete data or unclear outcome effects to ensure the completeness and accuracy of the analysis. For instance, “Teachers’ Emotion Regulation and Classroom Management”. Despite the fact that the content of this article is relevant, there is not enough data.

- Articles with weak relevance to important information related to the research variables, excluding articles in languages other than English.

- There are no quantitative components in the study (such as interview reports, focus group reports, classroom observation reports), for instance, “Measuring Language Teacher Emotion Regulation: Development and Validation of the Language Teacher Emotion Regulation Inventory at Workplace”.

3.3. Selected Studies

3.4. Coding

3.5. Statistical Analysis

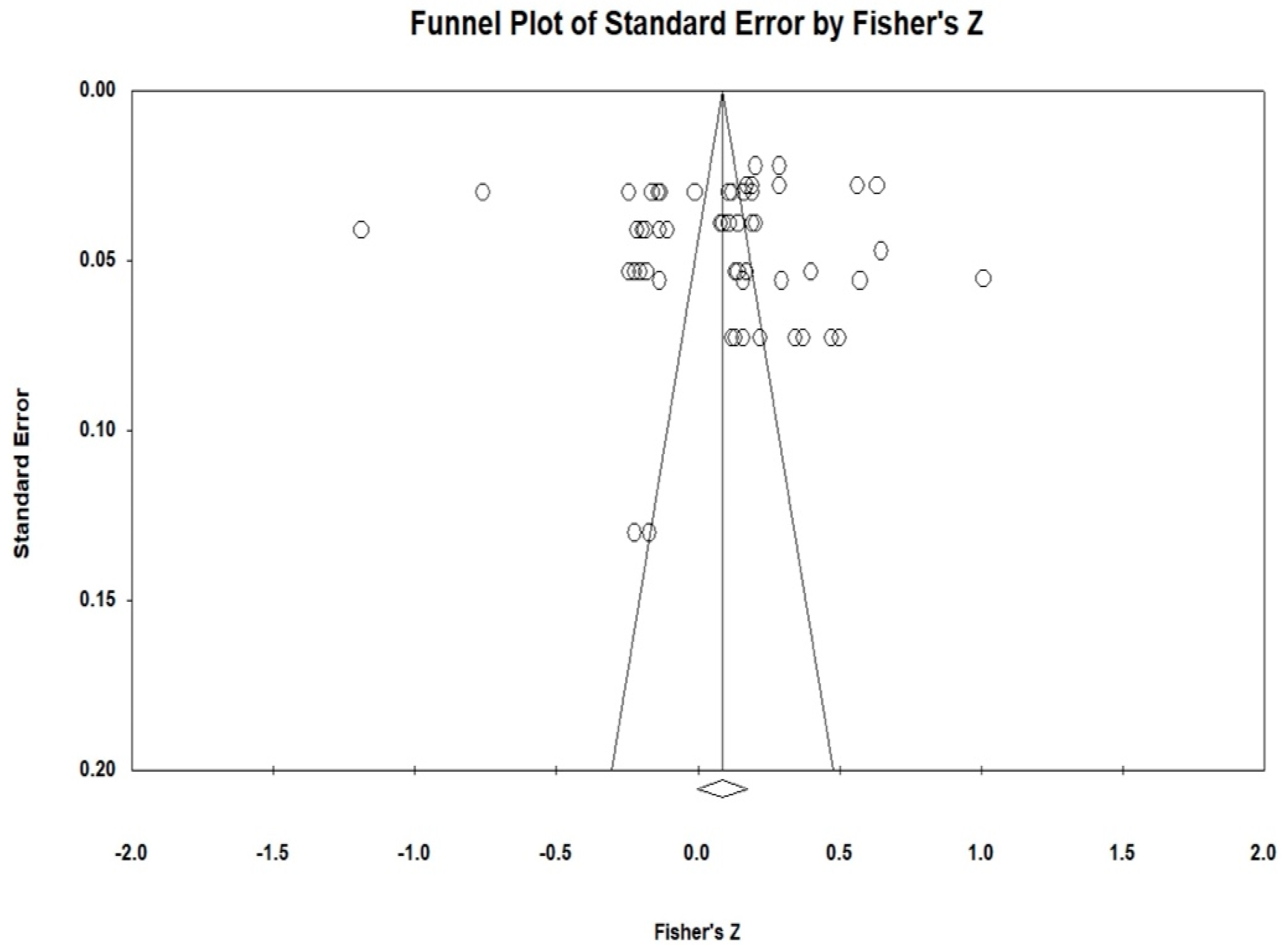

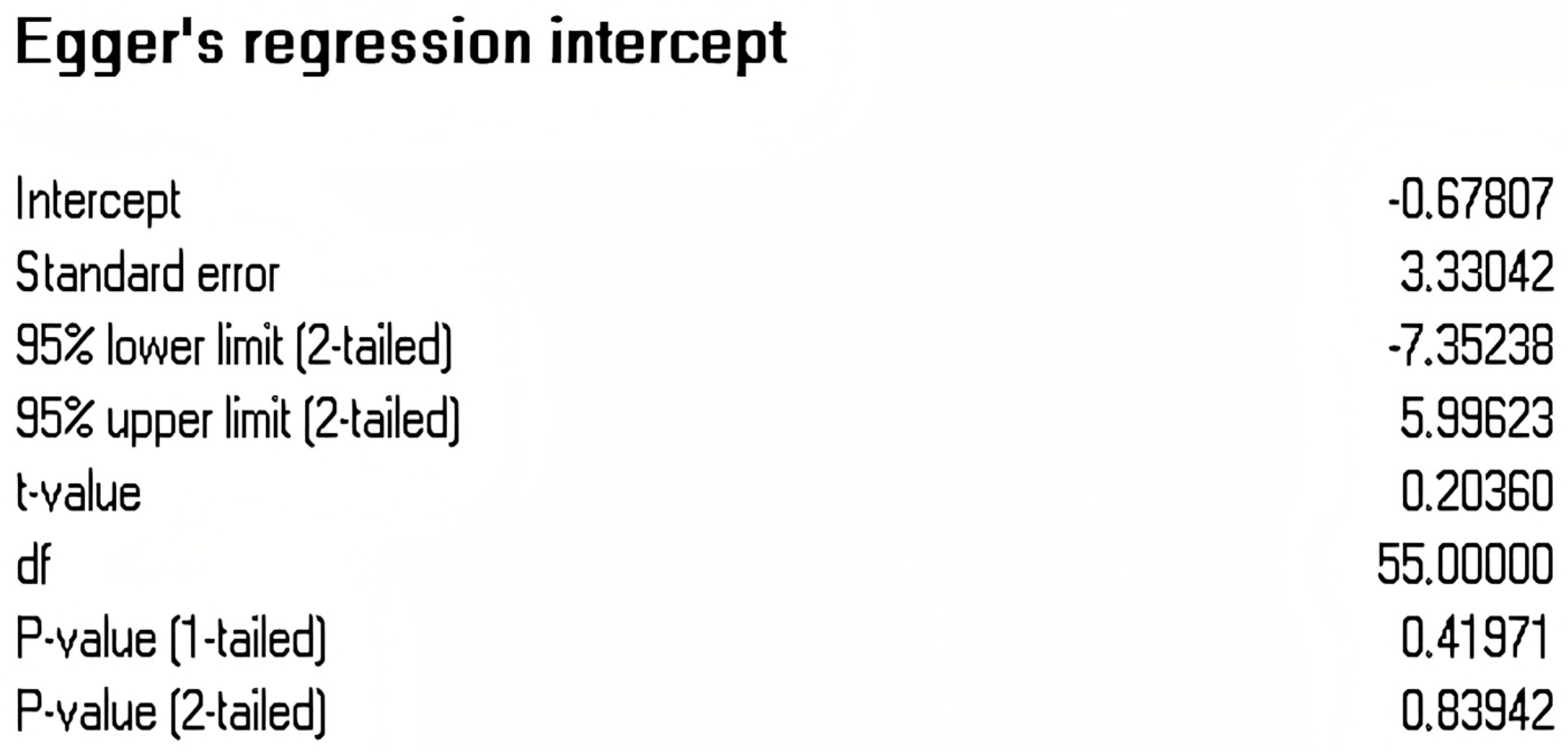

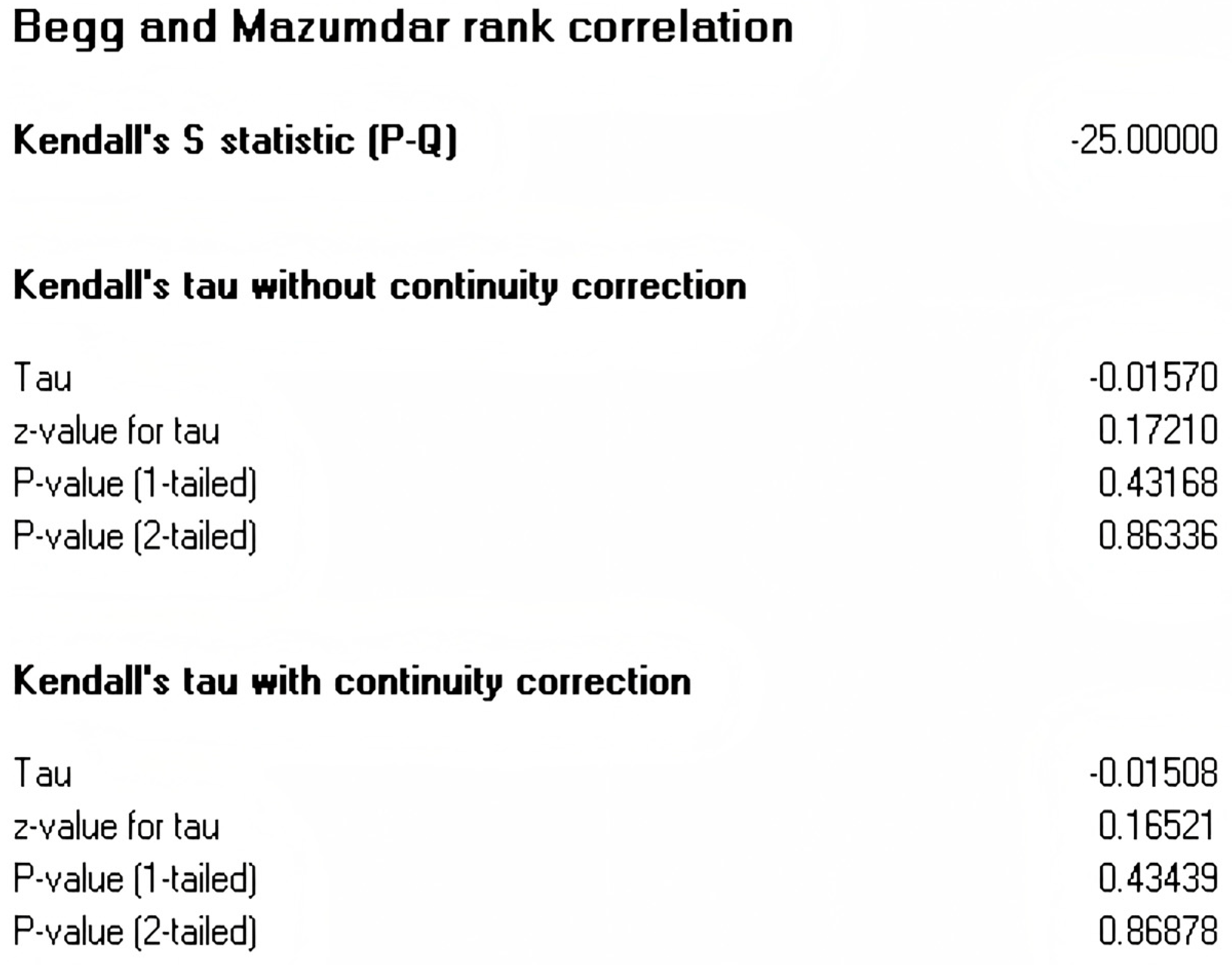

3.6. Publication Bias

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Findings

4.2. Effect Size Analysis

4.2.1. The Effect of Surface Acting on Teachers’ Emotions

4.2.2. The Effect of Deep Acting on Teachers’ Emotions

4.2.3. The Effect of Emotion Regulation on Teachers’ Emotions

4.2.4. The Effect of Reappraisal on Teachers’ Emotions

4.2.5. The Effect of Suppression on Teachers’ Emotions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barber, L. K., Grawitch, M. J., Carson, R. L., & Tsouloupas, C. N. (2010). Costs and benefits of supportive versus disciplinary emotion regulation strategies in teachers. Stress and Health, 27(3), e173–e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benesch, S. (2018). Emotions as agency: Feeling rules, emotion labor, and English language teachers’ decision-making. System, 79, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I., Slišković, A., & Macuka, I. (2017). A mixed-method approach to the assessment of teachers’ emotions: Development and validation of the Teacher Emotion Questionnaire. Educational Psychology, 38(3), 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I., Slišković, A., & Penezić, Z. (2018). A two-wave panel study on teachers’ emotions and emotional-labour strategies. Stress and Health, 27, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C. M., Chiu, P., & Lee, M. K. (2011). Online social networks: Why do students use facebook? Computers in Human Behavior, 27(4), 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DerSimonian, R., & Laird, N. (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials, 7(3), 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewaele, J., & Wu, A. (2021). Predicting the emotional labor strategies of Chinese English foreign language teachers. System, 103, 102660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenzel, A. C., Daniels, L., & Burić, I. (2021). Teacher emotions in the classroom and their implications for students. Educational Psychologist, 56(4), 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., & Sutton, R. E. (2009). Emotional transmission in the classroom: Exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(3), 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomb, T. M., & Tews, M. J. (2003). Emotional labor: A conceptualization and scale development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotion Regulation in the Workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandey, A. A., & Melloy, R. C. (2017). The state of the heart: Emotional labor as emotion regulation reviewed and revised. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A. A., & Sayre, G. M. (2019). Emotional Labor: Regulating emotions for a wage. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(2), 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2013). Emotion regulation: Taking stock and moving forward. Emotion, 13(3), 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). The Extended Process Model of Emotion Regulation: Elaborations, applications, and future directions. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenbarger, L., & Zembylas, M. (2006). The emotional labour of caring in teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(1), 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. B., & Chen, J. (2019). Emotions in education: Asian insights on the role of emotions in learning and teaching. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 28(4), 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinman, G., Wray, S., & Strange, C. (2011). Emotional labour, burnout and job satisfaction in UK teachers: The role of workplace social support. Educational Psychology, 31(7), 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S., & Eshet, R. (2018). Spiral effects of teachers’ emotions and emotion regulation strategies: Evidence from a daily diary study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 73, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. (2023). Investigating the effects of emotion regulation and creativity on Chinese EFL teachers’ burnout in online classes. Porta Linguarum Revista Interuniversitaria De Didáctica De Las Lenguas Extranjerasi, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D. (1999). The “Professional” work of experienced physical education teachers. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 70(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näring, G., Vlerick, P., & Van De Ven, B. (2011). Emotion work and emotional exhaustion in teachers: The job and individual perspective. Educational Studies, 38(1), 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Control-value theory of achievement emotions. In International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 120–141). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J., He, Y., Deng, J., Zheng, L., Chang, Y., & Liu, X. (2019). Emotional labor strategies and job burnout in preschool teachers: Psychological capital as a mediator and moderator. Work, 63(3), 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervaiz, S., Ali, A., & Asif, M. (2019). Emotional intelligence, emotional labor strategies and satisfaction of secondary teachers in Pakistan. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(4), 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R., & Linnenbrink, E. A. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: The role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(3), 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L. (2011). A survey study on the current status of teachers’ classroom emotional regulation abilities. Educational Research and Experiment, ((6)), 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Song, F. (1999). Exploring heterogeneity in meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 52(8), 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R. E. (2004). Emotional regulation goals and strategies of teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 7(4), 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R. E., & Harper, E. (2009). Teachers’ emotion regulation. In Springer eBooks (pp. 389–401). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R. E., Mudrey-Camino, R., & Knight, C. C. (2009). Teachers’ emotion regulation and classroom management. Theory Into Practice, 48(2), 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R. E., & Wheatley, K. F. (2003). Teachers’ emotions and teaching: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Educational Psychology Review, 15(4), 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J., & Zhou, J. (2024). Emotional regulation and emotional experience of foreign language writing teachers in the context of teacher feedback literacy. Foreign Language Teaching, ((5)), 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxer, J. L., & Frenzel, A. C. (2015). Facets of teachers’ emotional lives: A quantitative investigation of teachers’ genuine, faked, and hidden emotions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 49, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dillen, L. F., & Koole, S. L. (2007). Clearing the mind: A working memory model of distraction from negative mood. Emotion, 7(4), 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, E. A., Reschke, P. J., Main, A., & Shannon, R. M. (2020). The effect of emotional communication on infant’ distinct prosocial behaviors. Social Development, 29(4), 1092–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Burić, I., Chang, M.-L., & Gross, J. J. (2023). Teachers’ emotion regulation and related environmental, personal, instructional, and well-being factors: A meta-analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 26, 1651–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., & He, D. (2021). Emotional resilience and adaptive strategies of EFL teachers in technology-integrated classrooms: A self-determination theory perspective. Computers & Education, 173, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., & Huang, Y. (2020). The predictive effects of classroom environment and trait emotional intelligence on foreign language enjoyment and anxiety. System, 96, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., & Du, J. (2024). The effect of teacher self-efficacy, online pedagogical and content knowledge, and emotion regulation on teacher digital burnout: A mediation model. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H. (2012). Adaptation and validation of the teacher emotional labour strategy scale in China. Educational Psychology, 32(4), 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H., Huang, S., & Lee, J. C. K. (2017). Choose your strategy wisely: Examining the relationships between emotional labor in teaching and teacher efficacy in Hong Kong primary schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H., Huang, S., & Wang, W. (2016). Work environment characteristics and teacher well-being: The mediation of emotion regulation strategies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(9), 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yüksel, H. G., Solhi, M., Özcan, E., & Giritlioğlu, N. B. (2024). The associations between EFL learners’ L2 class belongingness, emotion regulation strategies, and perceived L2 proficiency in an online learning context. Language Learning Journal, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., & Zhu, W. (2008). Exploring Emotion in Teaching: Emotional labor, burnout, and satisfaction in Chinese higher education. Communication Education, 57(1), 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Studies Included | Journal Name | Sample Size | Participants | Emotion Regulation Strategies | Teachers’ Emotions | Correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | |||||||

| Value | |||||||

| 1 | (Yin, 2012) | Educational Psychology | 1281 | Primary and secondary teachers in China | surface acting | emotional labor | 0.51 |

| deep acting | emotional labor | 0.56 | |||||

| deep acting | job satisfaction | 0.28 | |||||

| deep acting | job satisfaction | 0.17 | |||||

| deep acting | job satisfaction | 0.19 | |||||

| 2 | (Burić et al., 2018) | Stress and Health | 2022 | Middle and high school teachers in Croatian | deep acting | emotional and psychological traits | 0.2 |

| deep acting | emotional and psychological traits | 0.28 | |||||

| 3 | (Yin et al., 2017) | Teaching and Teacher Education | 1115 | Primary school teachers in China | surface acting | emotional labor | −0.64 |

| surface acting | teaching efficacy | −0.14 | |||||

| surface acting | teaching efficacy | −0.16 | |||||

| surface acting | teaching efficacy | −0.24 | |||||

| deep acting | emotional labor | −0.01 | |||||

| deep acting | teaching efficacy | 0.19 | |||||

| deep acting | teaching efficacy | 0.11 | |||||

| deep acting | teaching efficacy | 0.12 | |||||

| 4 | (Peng et al., 2019) | Work (Reading, Mass.) | 355 | Preschool teachers in China | deep acting | emotional labor | 0.38 |

| deep acting | emotional and psychological traits | 0.14 | |||||

| deep acting | emotional and psychological traits | 0.13 | |||||

| deep acting | emotional and psychological traits | 0.17 | |||||

| deep acting | emotional and psychological traits | 0.13 | |||||

| surface acting | emotional labor | −0.18 | |||||

| surface acting | emotional and psychological traits | −0.24 | |||||

| surface acting | emotional and psychological traits | −0.22 | |||||

| surface acting | emotional and psychological traits | −0.24 | |||||

| surface acting | emotional and psychological traits | −0.2 | |||||

| 5 | (Pervaiz et al., 2019) | International Journal of Educational Management | 322 | Secondary teachers in Pakistan | surface acting | emotional and psychological traits | 0.52 |

| surface acting | emotional labor | 0.16 | |||||

| surface acting | job satisfaction | 0.29 | |||||

| deep acting | emotional labor | −0.14 | |||||

| 6 | (Barber et al., 2010) | Stress and Health | 659 | Chinese teachers | deep acting | emotional labor | 0.08 |

| deep acting | self-consciousness | 0.2 | |||||

| deep acting | self-consciousness | 0.19 | |||||

| deep acting | emotional labor | 0.19 | |||||

| surface acting | self-consciousness | 0.14 | |||||

| surface acting | self-consciousness | 0.09 | |||||

| surface acting | emotional labor | 0.11 | |||||

| surface acting | self-consciousness | 0.08 | |||||

| 7 | (Dewaele & Wu, 2021) | System | 594 | Chinese teachers | surface acting | language and creativity | −0.83 |

| surface acting | emotional and psychological traits | −0.11 | |||||

| surface acting | emotional and psychological traits | −0.21 | |||||

| surface acting | emotional and psychological traits | −0.13 | |||||

| surface acting | emotional labor | −0.18 | |||||

| surface acting | emotional and psychological traits | −0.19 | |||||

| 8 | (Lavy & Eshet, 2018) | Teaching and Teacher Education | 62 | Chinese teachers | surface acting | emotional and psychological traits | −0.17 |

| surface acting | job satisfaction | −0.22 | |||||

| 9 | (Yang & Du, 2024) | BMC Psychology | 450 | Chinese teachers | emotion regulation | emotional and psychological traits | 0.57 |

| 10 | (Yin et al., 2016) | Environ. Res. Public Health | 1115 | Chinese teachers | reappraisal | job satisfaction | 0.16 |

| suppression | job satisfaction | −0.13 | |||||

| 11 | (Yüksel et al., 2024) | The Language Learning Journal | 191 | University teacher in Turkey | reappraisal | social belongingness | 0.46 |

| reappraisal | social belongingness | 0.44 | |||||

| reappraisal | social belongingness | 0.33 | |||||

| reappraisal | social belongingness | 0.36 | |||||

| suppression | social belongingness | 0.12 | |||||

| suppression | social belongingness | 0.16 | |||||

| suppression | social belongingness | 0.22 | |||||

| suppression | social belongingness | 0.13 | |||||

| 12 | (Li, 2023) | Porta Lins. | 329 | All levels teacher in China | emotion regulation | language and creativity | 0.77 |

| Number of Effect Size | Effect Size (Point Estimate) | 95% CI Lower Limit | 95% CI Upper Limit | Z-Value | p-Value | Q-Value | df (Q) | p-Value (Q) | I2 | Tau2 | Standard Error | Variance | Tau |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57 | 0.086 | 0 | 0.17 | 1.95 | 0.051 | 3934.683 | 56 | 0.000 | 98.598 | 0.108 | 0.025 | 0.001 | 0.328 |

| Emotion Regulation Strategies | Teachers’ Emotion | k | r | p | 95%CI (LL, UL) | Heterogeneity | T | T2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | PQ | I2 | ||||||||

| Surface acting | Emotional and Psychological Traits | 10 | −0.131 | 0.099 | (−0.250, 0.022) | 178.859 | 0.000 | 94.968 | 0.215 | 0.046 |

| Emotional labor | 6 | −0.025 | 0.832 | (−0.463, 0.382) | 1085.184 | 0.000 | 99.539 | 0.563 | 0.317 | |

| Job satisfaction | 2 | 0.205 | 0.850 | (−0.429, 0.506) | 13.409 | 0.000 | 92.542 | 0.353 | 0.125 | |

| Language and Creativity | 1 | −0.830 | 0.000 | (−0.853, −0.803) | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Teaching Efficacy | 3 | 0.103 | 0.000 | (0.060, 0.147) | 1.391 | 0.499 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Total | 22 | −0.076 | 0.280 | (−0.281, 0.083) | 2116.483 | 0.000 | 99.008 | 0.442 | 0.195 | |

| Deep acting | Emotional and Psychological Traits | 6 | 0.215 | 0.000 | (0.130, 0.242) | 18.477 | 0.002 | 72.939 | 0.059 | 0.003 |

| Emotional labor | 6 | 0.222 | 0.130 | (−0.057, 0.417) | 339.155 | 0.000 | 98.536 | 0.310 | 0.096 | |

| Job satisfaction | 3 | 0.213 | 0.000 | (0.146, 0.280) | 9.788 | 0.007 | 79.568 | 0.055 | 0.003 | |

| Self-consciousness | 2 | 0.195 | 0.000 | (0.142, 0.246) | 0.035 | 0.851 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Teaching Efficacy | 3 | 0.140 | 0.000 | (0.090, 0.189) | 4.432 | 0.109 | 54.877 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Total | 20 | 0.201 | 0.000 | (0.119, 0.248) | 394.051 | 0.000 | 95.178 | 0.148 | 0.022 | |

| Emotion regulation | Emotional and Psychological Traits | 1 | 0.570 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Language and Creativity | 1 | 0.765 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Total | 2 | 0.668 | 0.000 | (0.441, 0.827) | 24.518 | 0.000 | 95.921 | 0.250 | 0.062 | |

| Reappraisal | Job satisfaction | 1 | 0.160 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Social belongingness | 4 | 0.397 | 0.000 | (0.334, 0.458) | 3.208 | 0.361 | 6.483 | 0.019 | 0.000 | |

| Total | 5 | 0.256 | 0.000 | (0.207, 0.475) | 33.556 | 0.000 | 88.080 | 0.162 | 0.026 | |

| Suppression | Job satisfaction | 1 | −0.130 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Social belongingness | 4 | 0.156 | 0.000 | (0.086, 0.225) | 1.118 | 0.773 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Total | 5 | −0.014 | 0.262 | (0.070, 0.252) | 38.464 | 0.000 | 89.601 | 0.175 | 3.064 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Zai, F.; Zhou, X. The Impact of Emotion Regulation Strategies on Teachers’ Well-Being and Positive Emotions: A Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030342

Wang Y, Zai F, Zhou X. The Impact of Emotion Regulation Strategies on Teachers’ Well-Being and Positive Emotions: A Meta-Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030342

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yi, Fengyu Zai, and Xiaoyong Zhou. 2025. "The Impact of Emotion Regulation Strategies on Teachers’ Well-Being and Positive Emotions: A Meta-Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030342

APA StyleWang, Y., Zai, F., & Zhou, X. (2025). The Impact of Emotion Regulation Strategies on Teachers’ Well-Being and Positive Emotions: A Meta-Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030342