Ephemeral Emotional Resonance: User-Perceived Functional Value Leading to Short-Form Video Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

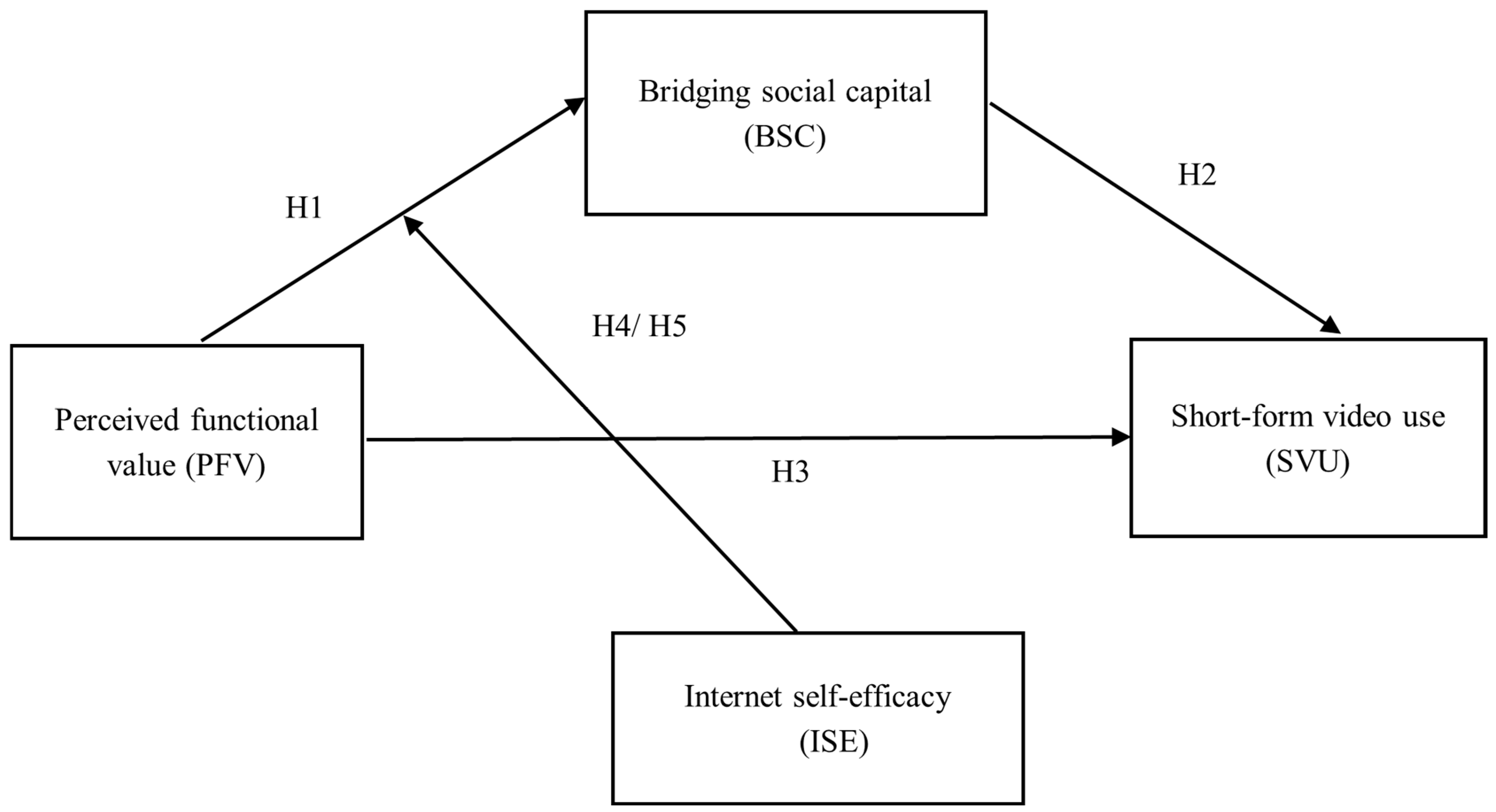

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Our General Theoretical Framework: Giddens’ Structuration

2.2. Perceived Functional Value and Bridging Social Capital

2.3. Bridging Social Capital and Short-Form Video Use

2.4. Perceived Functional Value, Bridging Social Capital, and Short-Form Video Use

2.5. Internet Self-Efficacy

3. Research Method

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Variable

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

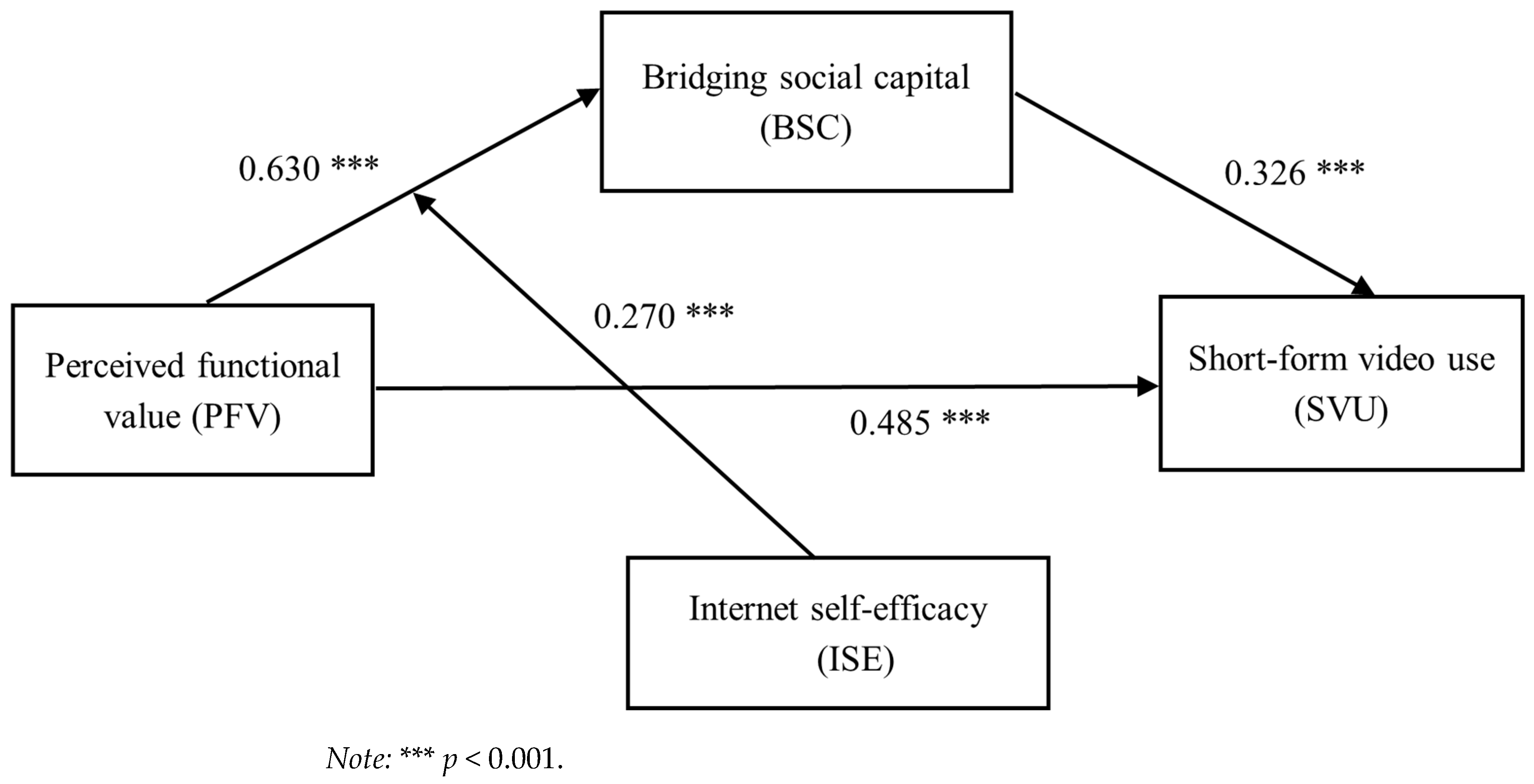

4.2. Testing for a Mediation Effect

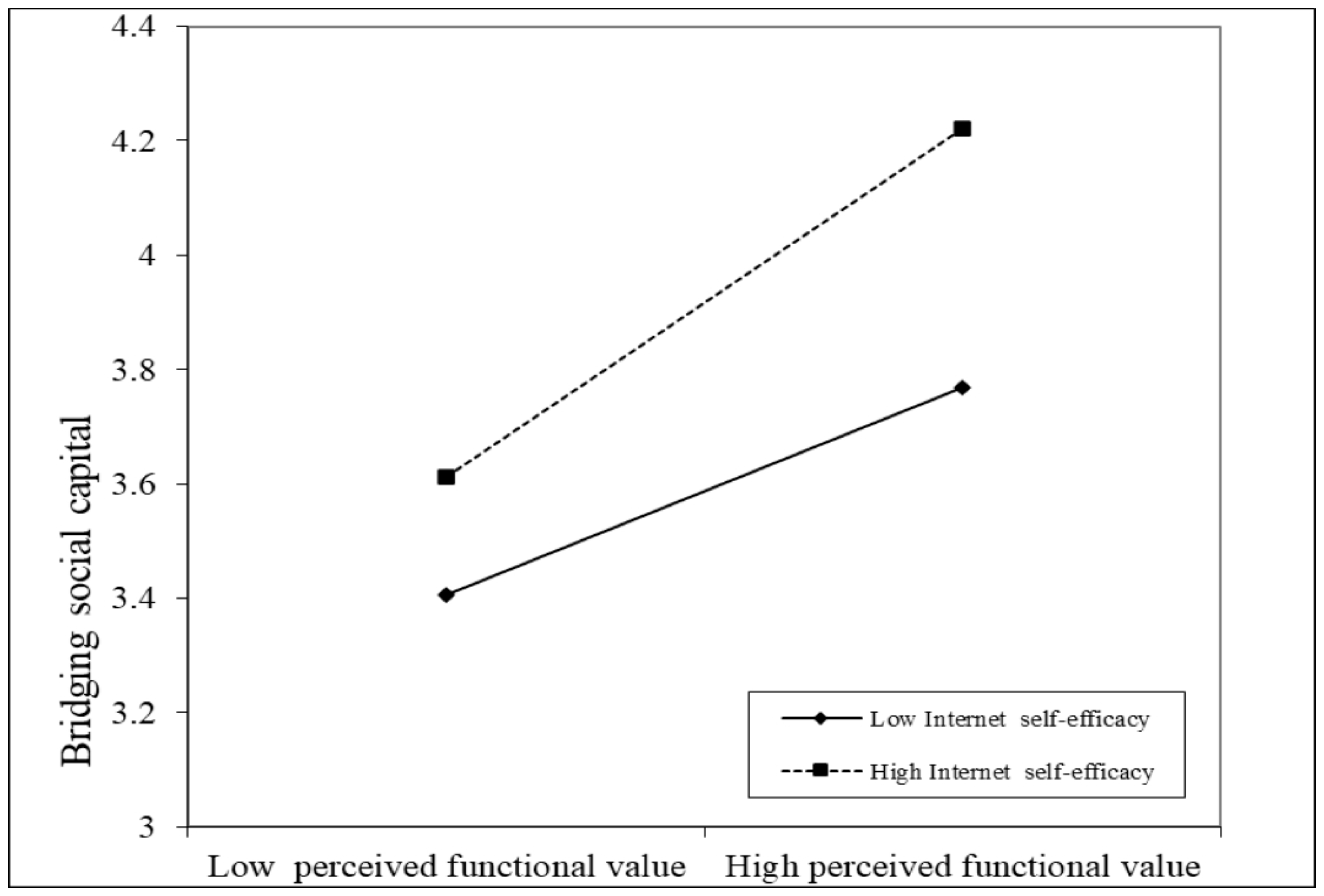

4.3. Testing for Moderation Effect

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, I., & Sexton, J. (1999). Depth of processing, belief congruence, and attitude-behavior correspondence. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(2), 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barta, S., Belanche, D., Fernández, A., & Flavián, M. (2023). Influencer marketing on TikTok: The effectiveness of humor and followers’ hedonic experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 70, 103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D. J., Preacher, K. J., & Gil, K. M. (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11(2), 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, D. (2008). Why youth (heart) social network sites: The role of networked publics in teenage social life. In D. Buckingham, D. John, & T. Catherine (Eds.), Youth, Identity, and digital media (2008 ed.). The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Y., Pini, B., & Pavlidis, A. (2024). Affective design and memetic qualities: Generating affect and political engagement through bushfire TikToks. Journal of Sociology, 60(1), 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervi, L., Tejedor, S., & Marín-Lladó, C. (2021). TikTok and the new language of political communication: The case of Podemos. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, 26, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. P., & Zhu, D. H. (2012). The role of perceived social capital and flow experience in building users’ continuance intention to social networking sites in China. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3), 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNNIC. (2020). The 45th China statistical report on internet development. pp. 1–2. Available online: https://www.cac.gov.cn/2020-04/27/c_1589535470378587.htm (accessed on 30 May 2020).

- Daugherty, T., Eastin, M., & Gangadharbatla, H. (2005). eCRM: Understanding internet confidence and the implications for customer relationship management. In Advances in electronic marketing (pp. 67–83). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- David, M. E., & Roberts, J. A. (2024). TikTok brain: An investigation of short-form video use, self-control, and phubbing. Social Science Computer Review, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bérail, P., Guillon, M., & Bungener, C. (2019). The relations between YouTube addiction, social anxiety and parasocial relationships with YouTubers: A moderated-mediation model based on a cognitive-behavioral framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X., Deng, N., Dong, X., Lin, Y., & Wang, J. (2019). Do others’ self-presentation on social media influence individual’s subjective well-being? A moderated mediation model. Telematics and Informatics, 41, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbaudo, P. (2024). TikTok and the algorithmic transformation of social media publics: From social networks to social in-terest clusters. New Media & Society, 14614448241304106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. (1984). Elements of the theory of structuration. In Practicing history: New directions in historical writing after the linguistic turn. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. (1986). Sociology: A brief but critical introduction. Macmillan International Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. S. (1977). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridakis, P., & Hanson, G. (2009). Social interaction and co-viewing with YouTube: Blending mass communication reception and social connection. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 53(2), 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Hayes, A. F., & Scharkow, M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science, 24(10), 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janis, F. H. M., Mohamed, S. S., Hashim, M. H., & Shan, L. W. (2024). Exploring TikTok’s role in political discourse: A content analysis of GE15 and SE2023 in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Research in Education and Social Sciences, 6(2), 288–299. [Google Scholar]

- Jokisch, M. R., Schmidt, L. I., Doh, M., Marquard, M., & Wahl, H. W. (2020). The role of internet self-efficacy, innovativeness and technology avoidance in breadth of internet use: Comparing older technology experts and non-experts. Computers in Human Behavior, 111, 106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur-Gill, S. (2023). The cultural customization of TikTok: Subaltern migrant workers and their digital cultures. Media International Australia, 186(1), 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. (2020). ‘If the rise of the TikTok dance and e-girl aesthetic has taught us anything, it’s that teenage girls rule the internet right now’: TikTok celebrity, girls and the Coronavirus crisis. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(6), 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & Um, N.-H. (2016). Recognition in social media for supporting a cause: Involvement and self-efficacy as moderators. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 44(11), 1863–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C. (2022). The making of a livestreaming village: Algorithmic practices and place-making in North Xiazhu. Chinese Journal of Communication, 15, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, L., Harlan, S. L., Bolin, B., Hackett, E. J., Hope, D., Kirby, A., Rex, T. R., & Wolf, S. (2004). Bonding and bridging: Understanding the relationship between social capital and civic action. Journal of Planning Education Research, 24(1), 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M. (2022). The end of social media? How data attraction model in the algorithmic media reshapes the attention economy. Media, Culture & Society, 44(6), 1110–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z., Zou, L., Zou, X., Wang, C., Zhang, B., Tang, D., Zhu, B., Zhu, Y., Wu, P., Wang, K., & Cheng, Y. (2022). Monolith: Real time recommendation system with collisionless embedding table. arXiv, arXiv:2209.07663. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, B., Cloudy, J., Hunter, J., & Potter, B. (2024). Stitch incoming: Political engagement and aggression on TikTok. Behaviour & Information Technology, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, D. (2022). Factors influencing Instagram Reels usage behaviours: An examination of motives, contextual age and narcissism. Telematics and Informatics Reports, 5, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C., Yang, H., & Elhai, J. D. (2021). On the psychology of TikTok use: A first glimpse from empirical findings. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 641673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J., Jin, E., & Zhuo, S. (2024). How perceived humor motivates and demotivates information processing of TikTok videos: The moderating role of TikTok gratifications. Health Communication, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, B., & Dequan, W. (2020). Watch, share or create: The influence of personality traits and user motivation on TikTok mobile video usage. International Association of Online Engineering, 14(4), 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, P. (1999). Is social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. American Journal of Sociology, 105(1), 88–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A. K., Murayama, K., DeHaan, C. R., & Gladwell, V. (2013). Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. (2001). Social capital: Measurement and consequences. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1), 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y., Omar, B., & Musetti, A. (2022). The addiction behavior of short-form video app TikTok: The information quality and system quality perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 932805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rach, M., & Peter, M. K. (2021). How TikTok’s algorithm beats Facebook & Co. for attention under the theory of escapism: A network sample analysis of Austrian, German and Swiss users. In F. J. Martínez-López, & D. López López (Eds.), Advances in digital marketing and eCommerce. DMEC 2021 (pp. 153–166). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintamäki, T., Kanto, A., Kuusela, H., & Spence, M. T. (2006). Decomposing the value of department store shopping into utilitarian, hedonic and social dimensions. International Journal of Retail Distribution Management, 37(1), 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnauber, A., & Mangold, F. (2020). Day-to-day routines of media platform use in the digital age: A structuration perspective. Communication Monographs, 87(4), 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrock, A. R. (2015). Communicative affordances of mobile media: Portability, availability, locatability, and multimediality. International Journal of Communication, 9, 1229–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Shane-Simpson, C., Manago, A., Gaggi, N., & Gillespie-Lynch, K. (2018). Why do college students prefer Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram? Site affordances, tensions between privacy and self-expression, and implications for social capital. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheer, V. C. (2011). Teenagers’ use of MSN features, discussion topics, and online friendship development: The impact of media richness and communication control. Communication Quarterly, 59(1), 82–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, L. A., & Taylor, K. (2007). Social networking on Facebook. Journal of the Communication, Speech & Theatre Association of North Dakota, 20, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam, K., Smahel, D., & Greenfield, P. (2006). Connecting developmental constructions to the Internet: Identity presentation and sexual exploration in online teen chat rooms. Developmental Psychology, 42(3), 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujon, Z., Viney, L., & Toker-Turnalar, E. (2018). Domesticating Facebook: The shift from compulsive connection to personal service platform. Social Media+ Society, 4(4), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J. C., & Soutar, G. N. (2001). Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Retailing, 77(2), 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teas, R. K., & Agarwal, S. (2000). The effects of extrinsic product cues on consumers’ perceptions of quality, sacrifice, and value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M. (2009). Social network sites: Users and uses. Advances in Computers, 76, 19–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkle, S. (2011). Alone together. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijck, J. (2009). Users like you? Theorizing agency in user-generated content. Media, Culture & Society, 31(1), 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vassey, J., Chang, H. C. H., Valente, T., & Unger, J. B. (2025). Worldwide connections of influencers who promote e-cigarettes on Instagram and TikTok: A social network analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 165, 108545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. L., Jackson, L. A., Wang, H. Z., & Gaskin, J. (2015). Predicting social networking site (SNS) use: Personality, attitudes, motivation and internet self-efficacy. Personality and Individual Differences, 80, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. (2020). Humor and camera view on mobile short-form video apps influence user experience and technology-adoption intent, an example of TikTok (DouYin). Computers in Human Behavior, 110, 106373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimann, G., & Masri, N. (2023). Research note: Spreading hate on TikTok. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 46(5), 752–765. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D. (2006). On and off the’Net: Scales for social capital in an online era. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2), 593–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R. B. (1997). Customer value: The next source for competitive advantage. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J. H., Wu, Y. T., Wu, Y. F., Chen, M. Y., & Ye, J. N. (2022). Effects of short video addiction on the motivation and well-being of chinese vocational college students. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 847672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S. J. (2014). Does social capital affect SNS usage? A look at the roles of subjective well-being and social identity. Computers in Human Behavior, 41, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Li, Y., Wu, B., & Li, D. (2017). How WeChat can retain users: Roles of network externalities, social interaction ties, and perceived values in building continuance intention. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. W. (2012). Internet use and demographic characteristics: Results from a national “Digital divide” survey. Journalism Research, 116, 10–19+72. [Google Scholar]

- Zulli, D., & Zulli, D. J. (2022). Extending the internet meme: Conceptualizing technological mimesis and imitation publics on the TikTok platform. New Media & Society, 24(8), 1872–1890. [Google Scholar]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 32.250 | 11.000 | |||||||

| 2. Gender | 1.490 | 0.500 | −0.157 ** | ||||||

| 3. Education | 3.550 | 0.982 | −0.220 ** | 0.208 ** | |||||

| 4. PFV | 3.923 | 0.511 | 0.013 | 0.111 ** | 0.141 ** | (0.733) | |||

| 5. BSC | 3.506 | 0.767 | 0.095 ** | −0.039 * | −0.062 ** | 0.402 ** | (0.737) | ||

| 6. SVU | 3.777 | 0.593 | 0.037 | 0.073 ** | 0.050 * | 0.594 ** | 0.588 ** | (0.736) | |

| 7. ISE | 3.843 | 0.575 | 0.036 | 0.025 | 0.163 ** | 0.608 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.480 ** | (0.728) |

| Predictors | Model 1 (Bridging Social Capital) | Model 2 (Short-Form Video Use) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | B | t | |

| Age | 0.004 | 3.236 ** | 0.000 | 0.0123 |

| Gender | −0.086 | −3.0531 ** | 0.049 | 2.860 ** |

| Education | −0.075 | −5.167 *** | 0.005 | 0.586 |

| PFV | 0.630 | 23.402 *** | 0.485 | 27.100 *** |

| BSC | 0.326 | 27.594 *** | ||

| R2 | 0.183 | 0.501 | ||

| F | 145.667 *** | 523.034 *** | ||

| Model 3 (Bridging Social Capital) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | t |

| Age | 0.004 | 3.022 ** |

| Gender | −0.061 | −2.196 * |

| Edu | −0.090 | −6.307 *** |

| PFV | −0.317 | −2.448 * |

| ISE | −0.529 | −3.942 ** |

| PFV × ISE | 0.270 | 6.111 *** |

| R2 | 0.219 | |

| F | 122.065 *** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, X.; Lin, Y.; Bai, Q. Ephemeral Emotional Resonance: User-Perceived Functional Value Leading to Short-Form Video Use. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030341

Xie X, Lin Y, Bai Q. Ephemeral Emotional Resonance: User-Perceived Functional Value Leading to Short-Form Video Use. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030341

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Xinzhou, Yanjun Lin, and Qiyu Bai. 2025. "Ephemeral Emotional Resonance: User-Perceived Functional Value Leading to Short-Form Video Use" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030341

APA StyleXie, X., Lin, Y., & Bai, Q. (2025). Ephemeral Emotional Resonance: User-Perceived Functional Value Leading to Short-Form Video Use. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030341