The Longitudinal Association Between Internet Addiction and Prosocial Behavior Among Chinese Adolescents: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Internet Addiction and Prosocial Behavior

1.2. The Mediating Effect of Self-Control

1.3. The Moderating Effect of Peer Rejection

1.4. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Internet Addiction

2.2.2. Peer Rejection

2.2.3. Self-Control

2.2.4. Prosocial Behavior

2.2.5. Covariates at T1

2.3. Data Analysis Plan

3. Results

3.1. Attrition Analysis

3.2. Common Method Bias

3.3. Descriptive and Correlations

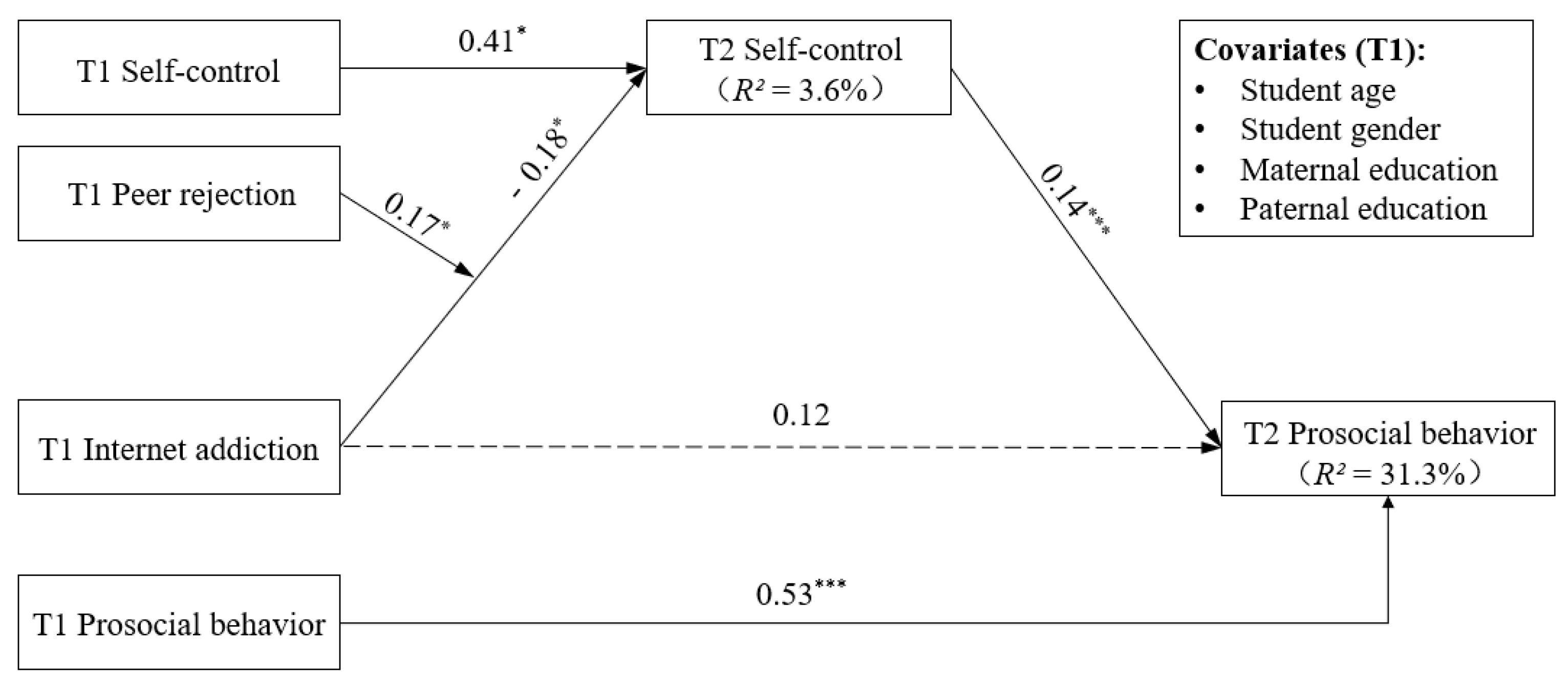

3.4. Mediating Effects of Self-Control

3.5. Moderating Effects of Peer Rejection

4. Discussion

4.1. Association Between Internet Addiction and Prosocial Behavior

4.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Control

4.3. The Moderating Role of Peer Rejection

4.4. Implications

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questionnaire | Items |

|---|---|

| Young Diagnostic Questionnaire (YDQ) Keys: 0 = No 1 = Yes | Do you feel preoccupied with the Internet (think about previous online activity or anticipate next online session)? |

| Do you feel the need to use the Internet with increasing amounts of time to achieve satisfaction? | |

| Have you repeatedly made unsuccessful efforts to control, cut back, or stop Internet use? | |

| Do you feel restless, moody, depressed, or irritable when attempting to cut down or stop Internet use? | |

| Do you stay online longer than originally intended? | |

| Have you jeopardized or risked the loss of a significant relationship, job, educational or career opportunity because of the Internet? | |

| Have you lied to family members, therapists, or others to conceal the extent of involvement with the Internet? | |

| Do you use the Internet as a way of escaping from problems or of relieving a dysphoric mood (e.g., feelings of helplessness, guilt, anxiety, depression)? | |

| Peer Rejection (PR) Keys: 1 = Totally disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Not sure 4 = Agree 5 = Totally agree | I sometimes feel as if some of my companions are ignoring me. |

| I think some of my peers may not allow me to participate in their activities. | |

| I suspect some of my companions are trying to avoid me. | |

| I feel like some of my peers have left me out of the conversation. | |

| I think some of my companions are more likely to pretend that I don’t exist. | |

| I think some companions may not ask me to play together. | |

| Brief Self-Control Scale (BSCS) Keys: 1 = Not like me at all 2 = A little like me 3 = Not sure 4 = Like me 5 = Very much like me | I am good at resisting temptation |

| I have a hard time breaking bad habit. | |

| I am lazy. | |

| I say inappropriate things. | |

| I do certain things that are bad for me, if they are fun. | |

| I refuse things that are bad for me. | |

| I wish I had more self-discipline. | |

| People would say that I have iron self- discipline. | |

| Pleasure and fun sometimes keep me from getting work done. | |

| I do many things on the spur of the moment. | |

| I can work effectively toward long-term goals. | |

| Sometimes I can’t stop myself from doing something, even if I know it is wrong | |

| I often act without thinking through all the alternatives. | |

| Prosocial Behavior (PB) Keys: 1 = Not true 2 = Somewhat true 3 = Certainly true | I try to be nice to other people, and I care about their feelings. |

| I usually share with others (food, games, pens etc.). | |

| I am helpful if someone is hurt, upset or feeling ill. | |

| I am kind to younger children. | |

| I often volunteer to help others (parents, teachers, children). |

References

- Alós-Ferrer, C., Hügelschäfer, S., & Li, J. (2015). Self-control depletion and decision making. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 8(4), 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsarrani, A., Hunter, R. F., Dunne, L., & Garcia, L. (2022). Association between friendship quality and subjective wellbeing among adolescents: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barragan-Jason, G., & Hopfensitz, A. (2023). Self-control is negatively linked to prosociality in young children. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 36(4), e2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, L., Rollo, S., Cafeo, A., Di Rosa, G., Pino, R., Gagliano, A., Germanò, E., & Ingrassia, M. (2024). Emotional and behavioural factors predisposing to internet addiction: The smartphone distraction among Italian high school students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(4), 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, D. V., Salmivalli, C., Garandeau, C. F., Berger, C., & Kanacri, B. P. L. (2022). Bidirectional associations of prosocial behavior with peer acceptance and rejection in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(12), 2355–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, W.-J., Huang, M.-F., Chang, Y.-P., Chen, Y.-M., Hu, H.-F., & Yen, C.-F. (2017). Social skills deficits and their association with Internet addiction and activities in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(1), 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, E., & Freeman, J. (2013). Do problematic and non-problematic video game players differ in extraversion, trait empathy, social capital and prosocial tendencies? Computers in Human Behavior, 29(5), 1933–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, K., Li, J. B., Wang, Y. J., Li, J. J., Liang, Z. Q., & Nie, Y. G. (2019). Engaging in prosocial behavior explains how high self-control relates to more life satisfaction: Evidence from three Chinese samples. PLoS ONE, 14(10), e0223169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, K., Wang, L.-X., Li, J.-B., Wang, G.-D., Li, Y.-Y., & Huang, Y.-T. (2020). Mobile phone addiction and risk-taking behavior among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N., & Mussen, P. H. (1989). The roots of prosocial behavior in children. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, C. J. (2015). Do angry birds make for angry children? A meta-analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior, and academic performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(5), 646–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, D. S. (2013). Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumero, A., Marrero, R. J., Voltes, D., & Peñate, W. (2018). Personal and social factors involved in internet addiction among adolescents: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gil, M. Á., Fajardo-Bullón, F., Rasskin-Gutman, I., & Sánchez-Casado, I. (2022). Problematic video game use and mental health among Spanish adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R., Meltzer, H., & Bailey, V. (1998). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 7(3), 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooren, E. M., van Lier, P. A., Stegge, H., Terwogt, M. M., & Koot, H. M. (2011). The development of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early elementary school children: The role of peer rejection. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(2), 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P., Zhou, Y., Li, D., Jia, J., Xiao, J., Liu, Y., & Zhang, H. (2023). Developmental trajectories of adolescent internet addiction: Interpersonal predictors and adjustment outcomes. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 51(3), 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joosten, A., van Dijke, M., Van Hiel, A., & De Cremer, D. (2015). Out of control!? How loss of self-control influences prosocial behavior: The role of power and moral values. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0126377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S., & Choi, E. (2015). Academic stress and internet addiction from general strain theory framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Hong, H., Lee, J., & Hyun, M.-H. (2017). Effects of time perspective and self-control on procrastination and Internet addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(2), 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K. M., McLaughlin, K. A., Silk, J., & Monahan, K. C. (2018). Peer effects on self-regulation in adolescence depend on the nature and quality of the peer interaction. Development and Psychopathology, 30(4), 1389–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, M. R., Twenge, J. M., & Quinlivan, E. (2006). Interpersonal rejection as a determinant of anger and aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(2), 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, L. M., & Juvonen, J. (2022). The academic benefits of maintaining friendships across the transition to high school. Journal of School Psychology, 92, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.-Q., Dou, K., Li, J.-B., Wang, Y.-J., & Nie, Y.-G. (2022). Linking self-control to negative risk-taking behavior among Chinese late adolescents: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Dang, J., Zhang, X., Zhang, Q., & Guo, J. (2014). Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: The effect of parental behavior and self-control. Computers in Human Behavior, 41, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Chen, Y., Lu, J., Li, W., & Yu, C. (2021). Self-control, consideration of future consequences, and internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: The moderating effect of deviant peer affiliation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(17), 9026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loparo, D., Fonseca, A. C., Matos, A. P., & Craighead, W. E. (2023). A developmental cascade analysis of peer rejection, depression, anxiety, and externalizing problems from childhood through young adulthood. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 51(9), 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H. K., Li, S. C., & Pow, J. W. (2011). The relation of Internet use to prosocial and antisocial behavior in Chinese adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(3), 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehroof, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2010). Online gaming addiction: The role of sensation seeking, self-control, neuroticism, aggression, state anxiety, and trait anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(3), 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, R. C., & Hay, C. (2012). Do peers matter in the development of self-control? Evidence from a longitudinal study of youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshi, D., & Ellithorpe, M. E. (2021). Problematic social media use and social support received in real-life versus on social media: Associations with depression, anxiety and social isolation. Addictive Behaviors, 119, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, B. D., & Wiemer-Hastings, P. (2005). Addiction to the internet and online gaming. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8(2), 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, Y., Kuzucu, Y., & Ak, Ş. (2014). Depression, loneliness and Internet addiction: How important is low self-control? Computers in Human Behavior, 34, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, P. S. (2019). Bridging the theory to evidence gap: A systematic review and analysis of individual × environment models of child development [Ph.D. thesis, Institute for Social Science Research, The University of Queensland]. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., Rigby, C. S., & Przybylski, A. (2006). The motivational pull of video games: A self-determination theory approach. Motivation and Emotion, 30(4), 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K., Upadyaya, K., Hakkarainen, K., Lonka, K., & Alho, K. (2017). The dark side of internet use: Two longitudinal studies of excessive internet use, depressive symptoms, school burnout and engagement among Finnish early and late adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situ, Q. M., Li, J. B., & Dou, K. (2016). Reexamining the linear and U-shaped relationships between self-control and emotional and behavioural problems. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 19(2), 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanković, M., Nešić, M., Čičević, S., & Shi, Z. (2021). Association of smartphone use with depression, anxiety, stress, sleep quality, and internet addiction. Empirical evidence from a smartphone application. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural Model Evaluation and Modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2), 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, L. R., Foster, E., Papandonatos, G. D., Handwerger, K., Granger, D. A., Kivlighan, K. T., & Niaura, R. (2009). Stress response and the adolescent transition: Performance versus peer rejection stressors. Development and Psychopathology, 21(1), 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M. (2014). Re-thinking internet gaming: From recreation to addiction. Addiction, 109(9), 1407–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sussman, S., Pokhrel, P., Ashmore, R. D., & Brown, B. B. (2007). Adolescent peer group identification and characteristics: A review of the literature. Addictive Behaviors, 32(8), 1602–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W., Han, X., Yu, H., Wu, Y., & Potenza, M. N. (2020). Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 113, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telzer, E. H., Masten, C. L., Berkman, E. T., Lieberman, M. D., & Fuligni, A. J. (2011). Neural regions associated with self control and mentalizing are recruited during prosocial behaviors towards the family. Neuroimage, 58(1), 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thau, S., Derfler-Rozin, R., Pitesa, M., Mitchell, M. S., & Pillutla, M. M. (2015). Unethical for the sake of the group: Risk of social exclusion and pro-group unethical behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L., Guo, M., Lu, Y., Liu, L., & Lu, Y. (2022). Risk-taking behavior among male adolescents: The role of observer presence and individual self-control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(11), 2161–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Graaff, J., Carlo, G., Crocetti, E., Koot, H. M., & Branje, S. (2018). Prosocial behavior in adolescence: Gender differences in development and links with empathy. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(5), 1086–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P., Zhao, M., Wang, X., Xie, X., Wang, Y., & Lei, L. (2017). Peer relationship and adolescent smartphone addiction: The mediating role of self-esteem and the moderating role of the need to belong. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Xie, Q., Xin, M., Wei, C., Yu, C., Zhen, S., Liu, S., Wang, J., & Zhang, W. (2020). Cybervictimization, depression, and adolescent internet addiction: The moderating effect of prosocial peer affiliation. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 572486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, G.-X., Gan, X., Jin, X., Zhang, Y.-H., & Zhu, C.-S. (2022). Developmental assets, self-control and internet gaming disorder in adolescence: Testing a moderated mediation model in a longitudinal study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 808264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y., & Qian, Z. (2023). The association between peer rejection and aggression types: A meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 135, 105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Li, P., Fu, X., & Kou, Y. (2017). Orientations to happiness and subjective well-being in Chinese adolescents: The roles of prosocial behavior and internet addictive behavior. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(6), 1747–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, J.-Y., Ko, C.-H., Yen, C.-F., Wu, H.-Y., & Yang, M.-J. (2007). The comorbid psychiatric symptoms of Internet addiction: Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), depression, social phobia, and hostility. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41(1), 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, M., Qiu, B., He, X., Tao, Z., Zhuang, C., Xie, Q., Tian, Y., & Zhang, W. (2022). Effects of reward and punishment in prosocial video games on attentional bias and prosocial behaviors. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, 107441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K. S. (2004). Internet addiction: A new clinical phenomenon and its consequences. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(4), 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Mo, P. K.-H., Zhang, J., Li, J., & Lau, J. T.-F. (2021). Impulsivity, self-control, interpersonal influences, and maladaptive cognitions as factors of internet gaming disorder among adolescents in China: Cross-sectional mediation study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(10), e26810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B., Li, D., Jia, J., Liu, Y., Sun, W., & Wang, Y. (2019). Peer victimization and problematic internet use in adolescents: The mediating role of deviant peer affiliation and the moderating role of family functioning. Addictive Behaviors, 96, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B., & Jin, C. (2023). Peer relationships and adolescent internet addiction: Variable-centered and person-centered approaches. Children and Youth Services Review, 155, 107243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., & Pan, Q. (2022). Effect of social-psychological intervention on self-efficacy, social adaptability and quality of life of internet-addicted teenagers. Psychiatria Danubina, 34(3), 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y., Yao, M., Fang, S., & Gao, X. (2022). A dual-process perspective to explore decision making in internet gaming disorder: An ERP study of comparison with recreational game users. Computers in Human Behavior, 128, 107104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuffianò, A., Eisenberg, N., Alessandri, G., Luengo Kanacri, B. P., Pastorelli, C., Milioni, M., & Caprara, G. V. (2016). The relation of pro-sociality to self-esteem: The mediational role of quality of friendships. Journal of Personality, 84(1), 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key variables | ||||||||

| 1. T1 Internet addiction | 0.24 | 0.27 | ||||||

| 2. T1 Peer rejection | 2.54 | 0.90 | 0.11 *** | |||||

| 3. T1 Self-control | 3.14 | 0.57 | −0.32 *** | −0.32 *** | ||||

| 4. T2 Self-control | 3.20 | 0.60 | −0.29 *** | −0.24 *** | 0.64 *** | |||

| 5. T1 Prosocial behavior | 2.46 | 0.40 | −0.25 *** | −0.16 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.24 *** | ||

| 6. T2 Prosocial behavior | 2.44 | 0.45 | −0.14 *** | −0.15 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.52 *** | |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Student age | 14.80 | 1.61 | 0.03 | 0.11 ** | −0.20 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.07 * | −0.07 * |

| Student gender | 1.455 | 0.50 | −0.31 *** | 0.10 ** | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.17 *** | 0.16 *** |

| Father’s level of education | 2.09 | 0.53 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Mother’s level of education | 1.94 | 0.59 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.12 *** | 0.03 | 0.07 * | 0.02 |

| Direct and Indirect Effects | Bias-Corrected Bootstrapped Estimates for Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% CI | β | |

| Direct Pathway | ||||

| T1 IA → T2 PB | 0.08 | 0.07 | [−0.057, 0.231] | 0.05 |

| Indirect Pathways | ||||

| T1 IA → T2 SC → T2 PB | −0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.061, −0.011] | −0.02 |

| T2 Self-Control (R2 = 3.6%) | T2 Prosocial Behavior (R2 = 31.3%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | β | B | SE | p | β | |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Student age | −0.001 | 0.01 | 0.926 | −0.003 | ||||

| Student gender | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.000 | 0.10 | ||||

| Father’s level of education | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.726 | 0.01 | ||||

| Mother’s level of education | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.644 | −0.02 | ||||

| Study variables | ||||||||

| T1 Internet addiction | −0.18 | 0.09 | 0.047 | −0.08 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.071 | 0.07 |

| T1 Peer rejection | −0.45 | 0.35 | 0.187 | −0.07 | ||||

| T1 IA × T1 PR | 0.17 | 0.79 | 0.027 | 0.07 | ||||

| T2 Self-control | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.000 | 0.19 | ||||

| T1 Prosocial behavior | 0.53 | 0.03 | 0.000 | 0.48 | ||||

| Levels of T1 Peer Rejection | B | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (M − 1SD) | −0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.089, −0.020] |

| Med (M) | −0.03 | 0.01 | [−0.055, −0.003] |

| High (M + 1SD) | −0.003 | 0.02 | [−0.036, 0.029] |

| Difference = High − Low | 0.05 | 0.02 | [0.007, 0.089] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, W.-X.; Ye, W.-Y.; Ng, K.-X.; Dou, K.; Ning, Z.-J. The Longitudinal Association Between Internet Addiction and Prosocial Behavior Among Chinese Adolescents: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030322

Liang W-X, Ye W-Y, Ng K-X, Dou K, Ning Z-J. The Longitudinal Association Between Internet Addiction and Prosocial Behavior Among Chinese Adolescents: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):322. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030322

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Wei-Xuan, Wan-Yu Ye, Kai-Xin Ng, Kai Dou, and Zhi-Jun Ning. 2025. "The Longitudinal Association Between Internet Addiction and Prosocial Behavior Among Chinese Adolescents: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030322

APA StyleLiang, W.-X., Ye, W.-Y., Ng, K.-X., Dou, K., & Ning, Z.-J. (2025). The Longitudinal Association Between Internet Addiction and Prosocial Behavior Among Chinese Adolescents: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030322