Two-Way Efforts Between the Organization and Employees: Impact Mechanism of a High-Commitment Human Resource System on Proactive Customer Service Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Hypotheses

2.1. High-Commitment Human Resource System and Proactive Customer Service Performance

2.2. The Mediating Role of Mission Valence

2.3. The Mediating Role of Work Meaning

2.4. Serial Mediation of Mission Valence and Work Meaning

3. Methods

3.1. Measurement

3.2. Samples

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.3. Correlation Analysis

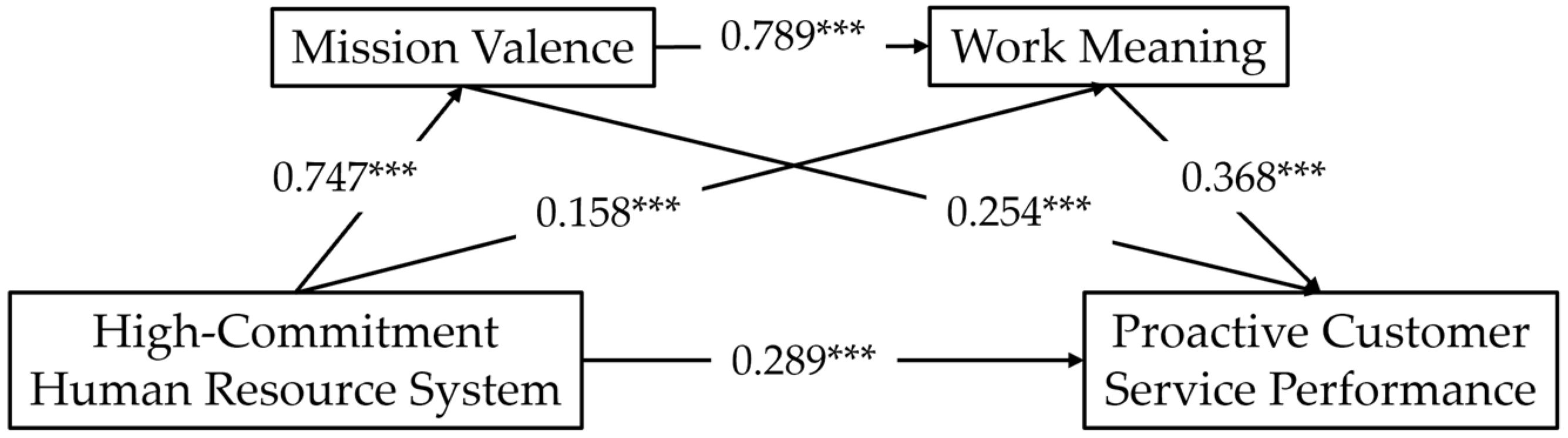

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Practical Implications

8. Limitations and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- The 7 items of Proactive Customer Service Performance Scale (Rank et al., 2007)

- I proactively share information with customers to meet their financial needs.

- I anticipate issues or needs customers might have and proactively develops solutions.

- I use own judgment and understanding of risk to determine when to make exceptions or improvise solutions.

- I take ownership by following through with the customer interaction and ensures a smooth transition to other service representatives.

- I actively create partnerships with other service representatives to better serve customers.

- I take initiative to communicate client requirements to other service areas and collaborates in implementing solutions.

- I proactively check with customers to verify that customer expectations have been met or exceeded.

- The 4 items of Mission Valence Scale (Pandey et al., 2008)

- This organization provides valuable public services.

- I believe that the priorities of this organization are quite important.

- The work of this organization is not very significant in the broader scheme of things.

- For me, the mission of this organization is exciting.

- The 10 items of Work Meaning Scale (Steger et al., 2012)

- I have found a meaningful career.

- I view my work as contributing to my personal growth.

- My work really makes no difference to the world.

- I understand how my work contributes to my life’s meaning.

- I have a good sense of what makes my job meaningful.

- I know my work makes a positive difference in the world.

- My work helps me better understand myself.

- I have discovered work that has a satisfying purpose.

- My work helps me make sense of the world around me.

- The work I do serves a greater purpose.

- The 15 items of High-Commitment Human Resource System Scale (Xiao & Björkman, 2006)

- Promotion from within rather than from outside.

- Careful selection procedures in recruiting.

- Extensive training and socialization.

- Trying not to fire employees.

- Enlarged jobs and job rotation.

- Appraisal of team performance rather than individual performance.

- Attitude and behaviour-oriented appraisal rather than result-oriented appraisal.

- Feedback for development purposes rather than for evaluation purposes.

- High remuneration, including compensation and fringe benefits.

- Extensive ownership of shares, options or profit-sharing.

- Trying to promote egalitarianism in income, status and culture.

- Participation in forms of suggestion, grievance systems and morale survey.

- Open communication and wide information sharing.

- Emphasizing strong overarching goals.

- Work in teams; successes of teams rather than individual are hailed.

References

- Abuelhassan, A. E., & AlGassim, A. (2022). How organizational justice in the hospitality industry influences proactive customer service performance through general self-efficacy. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(7), 2579–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shaer, A. S., Jabeen, F., Jose, S., & Farouk, S. (2023). Cultural intelligence and proactive service performance: Mediating and moderating role of leader’s collaborative nature, cultural training and emotional labor. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 37(3), 379–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C., & Madden, A. (2016). What makes work meaningful—Or meaningless? MIT Sloan Management Review, 57, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Batt, R. (2002). Managing customer services: Human resource practices, quit rates, and sales growth. Academy of Management Journal, 45(3), 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Tetreault, M. S. (1990). The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable Incidents. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. M. (2017). Exchange and power in social life. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-Translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillier, J. G. (2016). Do Transformational leaders affect turnover intentions and extra-role behaviors through mission valence? The American Review of Public Administration, 46(2), 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Lyu, Y., Li, Y., Zhou, X., & Li, W. (2017). The impact of high-commitment hr practices on hotel employees’ proactive customer service performance. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 58(1), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., & Xiao, M. (2020). High commitment human resource practice and technology enterprise performance: Regulated mediation model. Science and Technology Management Research, 40(08), 156–165. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B., Dong, Y., Zhou, X., Guo, G., & Peng, Y. (2020). Does customer incivility undermine employees’ service performance? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 89, 102544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C. J., & Smith, K. G. (2006). Knowledge exchange and combination: The role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3), 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior (Vol. 3). Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H., & Mao, J. (2022). Human-machine collaboration and reshaping of employees’ sense of work meaning in process of digital transformation. Enterprise Economy, 41(11), 15–27+12. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J., Shi, J., & Ling, B. (2017). The influence of high commitment organization on employee voice behavior: A dual-process model examination. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 49(04), 539–553. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z., Ren, M., Sun, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhou, W., & Chen, X. (2025). How does procedural justice affect job crafting? the role of organizational psychological ownership and high-performance work systems. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, S., & Chênevert, D. (2021). Municipal employees’ performance and neglect: The effects of mission valence. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 41(3), 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. The American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership, and organization: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 9(1), 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y., Chen, Z., Lam, W., & Woods, S. A. (2019). Standing in my customer’s shoes: Effects of customer-oriented perspective taking on proactive service performance. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(2), 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L., Ye, Y., & Deng, X. (2022). From shared leadership to proactive customer service performance: A multilevel investigation. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(11), 3944–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z., & Xu, S. (2023). Multitasking and employees’ proactive behavior: The roles of work meaningfulness, paradox mindset and challenge appraisal. Human Resources Development of China, 40(04), 35–48. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M. J., & Jiang, L. (2017). Reaping the benefits of meaningful work: The mediating versus moderating role of work engagement. Stress and Health, 33(3), 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, Z., Chen, J., & Zhao, S. (2024). Perceived non-decent work and proactive customer service performance of digital gig workers. Research on Economics and Management, 45(04), 76–92. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kosfeld, M., Neckermann, S., & Yang, X. (2017). The effects of financial and recognition incentives across work contexts: The role of meaning. Economic Inquiry, 55(1), 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, F., Guest, D., Ramos, J., & Gracia, F. J. (2016). High commitment HR practices, the employment relationship and job performance: A test of a mediation model. European Management Journal, 34(4), 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P. Y. Y., Tong, J. L. Y. T., Lien, B. Y.-H., Hsu, Y.-C., & Chong, C. L. (2017). Ethical work climate, employee commitment and proactive customer service performance: Test of the mediating effects of organizational politics. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 35, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y., & Chen, Z. (2018). A study on the relationship between public servants’ mission valence and job vigor: From the perspective of conservation of resource. Journal of Xiamen University (Arts & Social Sciences), 68(05), 123–134. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Lips-Wiersma, M., & Wright, S. (2012). Measuring the meaning of meaningful work: Development and validation of the comprehensive meaningful work scale (CMWS). Group & Organization Management, 37(5), 655–685. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y., & Hu, Y. (2023). Research on the influence of customer gratitude expression on employee proactive service behavior. East China Economic Management, 37(7), 120–128. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- McClean, E., & Collins, C. (2011). High-commitment HR practices, employee effort, and firm performance: Investigating the effects of HR practices across employee groups within professional services firms. Human Resource Management, 50, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S. K., Wright, B. E., & Moynihan, D. P. (2008). Public service motivation and interpersonal citizenship behavior in public organizations: Testing a preliminary model. International Public Management Journal, 11(1), 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J., Liu, S., Cui, X., Zhang, Z., & Ge, C. (2022). Dose algorithmic control motivates gig workers to offer the proactive services? Based on the perspective of work motivation. Nankai Business Review, 1–19. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Rainey, H. G., & Steinbauer, P. (1999). Galloping elephants: Developing elements of a theory of effective government organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 9(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, J., Carsten, J. M., Unger, J. M., & Spector, P. E. (2007). Proactive customer service performance: Relationships with individual, task, and leadership variables. Human Performance, 20(4), 363–390. [Google Scholar]

- Raub, S., & Liao, H. (2012). Doing the right thing without being told: Joint effects of initiative climate and general self-efficacy on employee proactive customer service performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 651–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rod, M., Ashill, N. J., & Gibbs, T. (2016). Customer perceptions of frontline employee service delivery: A study of Russian bank customer satisfaction and behavioural intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 30, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, T., Höge, T., & Pollet, E. (2013). Predicting meaning in work: Theory, data, implications. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siami, S., Martin, A., Gorji, M., & Grimmer, M. (2022). How discretionary behaviors promote customer engagement: The role of psychosocial safety climate and psychological capital. Journal of Management & Organization, 28(2), 379–397. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M., Huang, Z., Hu, H., & Qi, M. (2018). Literature review and future prospect on work meaningfulness. Human Resources Development of China, 35(09), 85–96. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Song, S. Q., Zhou, J., & Lv, B. Y. (2023). Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on proactive customer service performance. Social Behavior and Personality, 51(7), e12406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, M. (2018). The proactive employee on the floor of the store and the impact on customer satisfaction. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 43, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A., Pearce, J., Porter, L. W., & Hite, J. P. (1995). Choice of employee-organization relationship: Influence of external and internal organizational factors. In G. R. Ferris (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resource management (Vol. 13, pp. 117–151). JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., Gao, J., Feng, L., & Tang, X. (2021). Research on the concept, influence and mechanism of weak proactive customer service performance. Journal of Management World, 37(1), 150–169+110. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Wright, B. E., Moynihan, D. P., & Pandey, S. K. (2012). Pulling the levers: Transformational leadership, public service motivation, and mission valence. Public Administration Review, 72(2), 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(1), 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-Z., Ye, Y., Cheng, X.-M., Kwan, H. K., & Lyu, Y. (2020). Fuel the service fire: The effect of leader humor on frontline hospitality employees’ service performance and proactive customer service performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(5), 1755–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z., & Björkman, I. (2006). High Commitment work systems in Chinese organizations: A preliminary measure. Management and Organization Review, 2, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z., Mansor, Z. D., & Choo, W. C. (2023). Family incivility, emotional exhaustion, and hotel employees’ outcomes: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(9), 3053–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2023). Mission valence: A review and prospects. Foreign Economics & Management, 45(05), 101–116. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S., Chen, Z., & Guo, J. (2022). A research on the effects of front–line civil servants’ public service motivation on proactive behaviors. Public Administration and Policy Review, 11(03), 52–63. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zang, D., Liu, C., & Jiao, Y. (2021). Abusive supervision, affective commitment, customer orientation, and proactive customer service performance: Evidence from hotel employees in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G., & Liu, Y. (2019). Research on the influence mechanism of social responsible human resource management on proactive service behavior of employees. Human Resources Development of China, 36(5), 6–21. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., Ma, H., Liu, Y., Shi, Y., & Tang, H. (2018). A study review on proactive customer service performance: Background, conceptualization and influence mechanism. Human Resources Development of China, 35(3), 41–51. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., Zhou, Z. E., Ma, H., & Tang, H. (2021). Customer-initiated support and employees’ proactive customer service performance: A multilevel examination of proactive motivation as the mediator. Applied Psychology, 70(3), 1154–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Zhang, Z., Liu, N., & Ding, M. (2016). A literature review on new development of self-determination theory. Chinese Journal of Management, 13(7), 1095–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H., Lyu, Y., Deng, X., & Ye, Y. (2017). Workplace ostracism and proactive customer service performance: A conservation of resources perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 64, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) | ||

| Variable | Form | Percentage (%) |

| gender | Male | 45.6 |

| Female | 54.4 | |

| age | 24 and below | 10.6 |

| 25–29 | 32.3 | |

| 30–34 | 31.7 | |

| 35–39 | 17.2 | |

| 40–44 | 3.9 | |

| 45 and above | 4.2 | |

| education | junior high school and below | 2.1 |

| high school/technical secondary school | 7.3 | |

| junior college | 11.8 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 58.6 | |

| Master’s degree and above | 20.2 | |

| marital status | unmarried | 39.0 |

| married | 59.5 | |

| divorced | 1.5 | |

| year of entry into the organization | 1 year and shorter | 11.5 |

| 1–3 | 27.2 | |

| 3–5 | 47.1 | |

| 5–7 | 11.2 | |

| 8–10 | 1.8 | |

| 10 and longer | 1.2 | |

| (b) | ||

| Variable | Form | Percentage (%) |

| size of the organization | Less than 10 people, or annual operating income of less than CNY 1 million | 2.1 |

| 10 to 100 people, or an annual operating income of CNY 1 million to 20 million | 16.3 | |

| 100 to 300 people, or an annual operating income of CNY 20 million to 100 million | 68.0 | |

| More than 300 people, or an annual operating income of more than CNY 100 million | 13.6 | |

| year of establishment of the organization | 1 year and shorter | 0.3 |

| 1–3 | 5.1 | |

| 3–5 | 14.8 | |

| 5–7 | 12.7 | |

| 8–10 | 45.3 | |

| 10 years and longer | 21.8 | |

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| four-factor model (HCHRS/MV/WM/PCSP) | 1085.336 | 583 | 1.862 | 0.912 | 0.904 | 0.911 | 0.051 | 0.051 |

| three-factor model (HCHRS/MV + WM/PCSP) | 1250.412 | 591 | 2.116 | 0.885 | 0.876 | 0.884 | 0.058 | 0.056 |

| two-factor model (HCHRS/MV +WM + PCSP) | 1268.371 | 593 | 2.139 | 0.882 | 0.874 | 0.881 | 0.059 | 0.057 |

| single-factor model (HCHRS + MV +WM + PCSP) | 1330.115 | 594 | 2.239 | 0.871 | 0.862 | 0.870 | 0.061 | 0.057 |

| Variable Name | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. HCHRS | 1 | ||||||||||

| 2. MV | 0.747 *** | 1 | |||||||||

| 3. WM | 0.754 *** | 0.804 *** | 1 | ||||||||

| 4. PCSP | 0.748 *** | 0.907 *** | 0.815 *** | 1 | |||||||

| 5. gender | −0.159 ** | −0.244 *** | −0.184 ** | −0.285 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 6. age | −0.145 ** | −0.179 ** | −0.229 *** | −0.217 *** | 0.280 *** | 1 | |||||

| 7. education | 0.217 *** | 0.208 *** | 0.229 *** | 0.177 ** | 0.146 ** | −0.224 *** | 1 | ||||

| 8. marital status | −0.148 ** | −0.209 *** | −0.230 *** | −0.245 *** | 0.229 *** | 0.675 *** | −0.062 | 1 | |||

| 9. year of entry into the organization | −0.001 | −0.006 | −0.041 | −0.027 | 0.127 * | 0.503 *** | −0.007 | 0.530 *** | 1 | ||

| 10. year of establishment of the organization | 0.042 | 0.062 | 0.069 | 0.056 | −0.070 | 0.048 | −0.108 * | 0.051 | 0.071 | 1 | |

| 11. size of the organization | −0.111 ** | −0.012 | −0.044 | −0.075 | 0.025 | −0.031 | 0.167 ** | −0.035 | −0.053 | 0.234 *** | 1 |

| Mean | 3.685 | 3.606 | 3.556 | 3.845 | 1.540 | 2.840 | 3.880 | 1.630 | 2.680 | 4.630 | 2.930 |

| SD | 0.563 | 0.984 | 0.867 | 0.663 | 0.499 | 1.198 | 0.887 | 0.515 | 0.962 | 1.146 | 0.616 |

| Variable Name | MV | WM | PCSP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| HCHRS | 0.703 *** | 0.690 *** | 0.150 *** | 0.709 *** | 0.336 *** | 0.321 *** | 0.282 *** | |

| MV | 0.877 *** | 0.767 *** | 0.530 *** | 0.249 *** | ||||

| WM | 0.562 *** | 0.366 *** | ||||||

| gender | −0.129 ** | −0.155 *** | −0.054 * | −0.056 * | −0.046 | 0.023 | 0.042 | 0.043 |

| age | 0.023 | −0.006 | −0.024 | −0.024 | −0.057 | −0.069 | −0.054 | −0.061 |

| education | 0.066 | 0.045 | 0.008 | −0.005 | 0.066 | 0.031 | 0.040 | 0.033 |

| marital status | −0.120 * | −0.138 ** | −0.045 | −0.046 | −0.097 | −0.033 | −0.019 | −0.017 |

| year of entry in the organization | 0.065 | 0.068 | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.043 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.002 |

| year of establishment of the organization | −0.019 | 0.026 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.045 | 0.035 | 0.031 | 0.031 |

| size of the organization | 0.054 | −0.011 | −0.071 ** | −0.052 * | 0.011 | −0.018 | 0.017 | 0.001 |

| R2 | 0.582 | 0.593 | 0.830 | 0.839 | 0.585 | 0.701 | 0.712 | 0.722 |

| ΔR2 | 0.430 | 0.413 | 0.644 | 0.653 | 0.437 | 0.552 | 0.563 | 0.573 |

| Path | β | se | p | 95% CI (PC) | 95% CI (BC) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCL | LLCL | ULCL | ULCL | ||||

| HCHRS→PCSP (direct effect) | 0.289 | 0.062 | <0.001 | 0.222 | 0.462 | 0.220 | 0.461 |

| HCHRS→MV→PCSP | 0.224 | 0.074 | 0.002 | 0.082 | 0.373 | 0.089 | 0.381 |

| HCHRS→WM→PCSP | 0.069 | 0.023 | <0.001 | 0.028 | 0.120 | 0.030 | 0.124 |

| HCHRS→MV→WM→PCSP | 0.256 | 0.059 | <0.001 | 0.138 | 0.373 | 0.138 | 0.374 |

| total effect | 0.754 | 0.051 | <0.001 | 0.786 | 0.989 | 0.783 | 0.986 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zang, D.; Lyu, B. Two-Way Efforts Between the Organization and Employees: Impact Mechanism of a High-Commitment Human Resource System on Proactive Customer Service Performance. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030321

Zang D, Lyu B. Two-Way Efforts Between the Organization and Employees: Impact Mechanism of a High-Commitment Human Resource System on Proactive Customer Service Performance. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):321. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030321

Chicago/Turabian StyleZang, Dexia, and Boyi Lyu. 2025. "Two-Way Efforts Between the Organization and Employees: Impact Mechanism of a High-Commitment Human Resource System on Proactive Customer Service Performance" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030321

APA StyleZang, D., & Lyu, B. (2025). Two-Way Efforts Between the Organization and Employees: Impact Mechanism of a High-Commitment Human Resource System on Proactive Customer Service Performance. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030321