Alcohol and Cannabis Perceived Descriptive and Injunctive Norms, Personal Use, and Consequences Among 2-Year College Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Perceived Social Norms as a Proximal Risk Factor

1.2. The Reference Group

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Screening Survey

2.2.2. Follow-Up Survey

2.3. Analytic Strategy

- Aim 1: To determine prevalence rates of alcohol and cannabis use among 2-year college students, we descriptively examined use among the large screening sample of 2-year students.

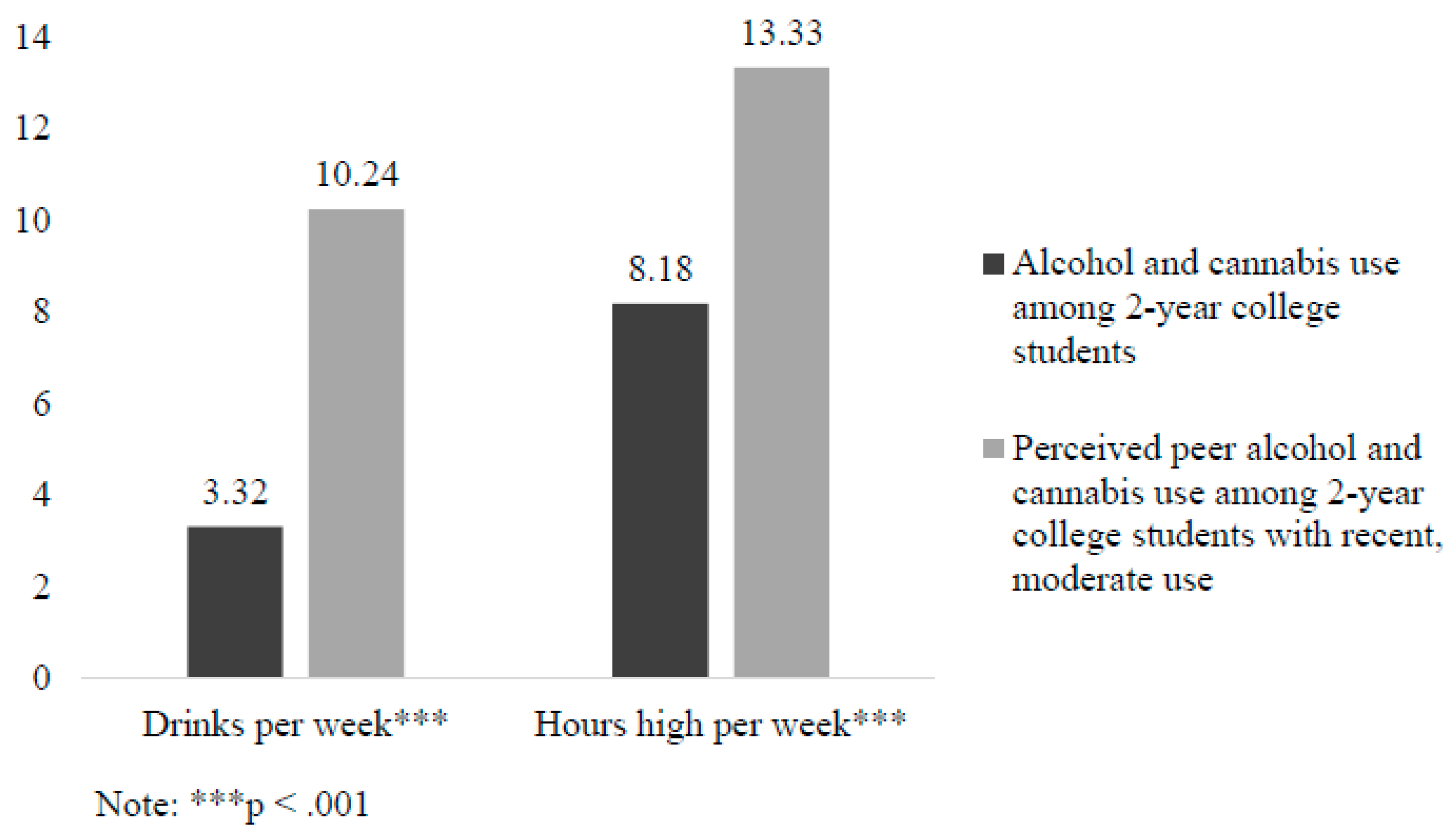

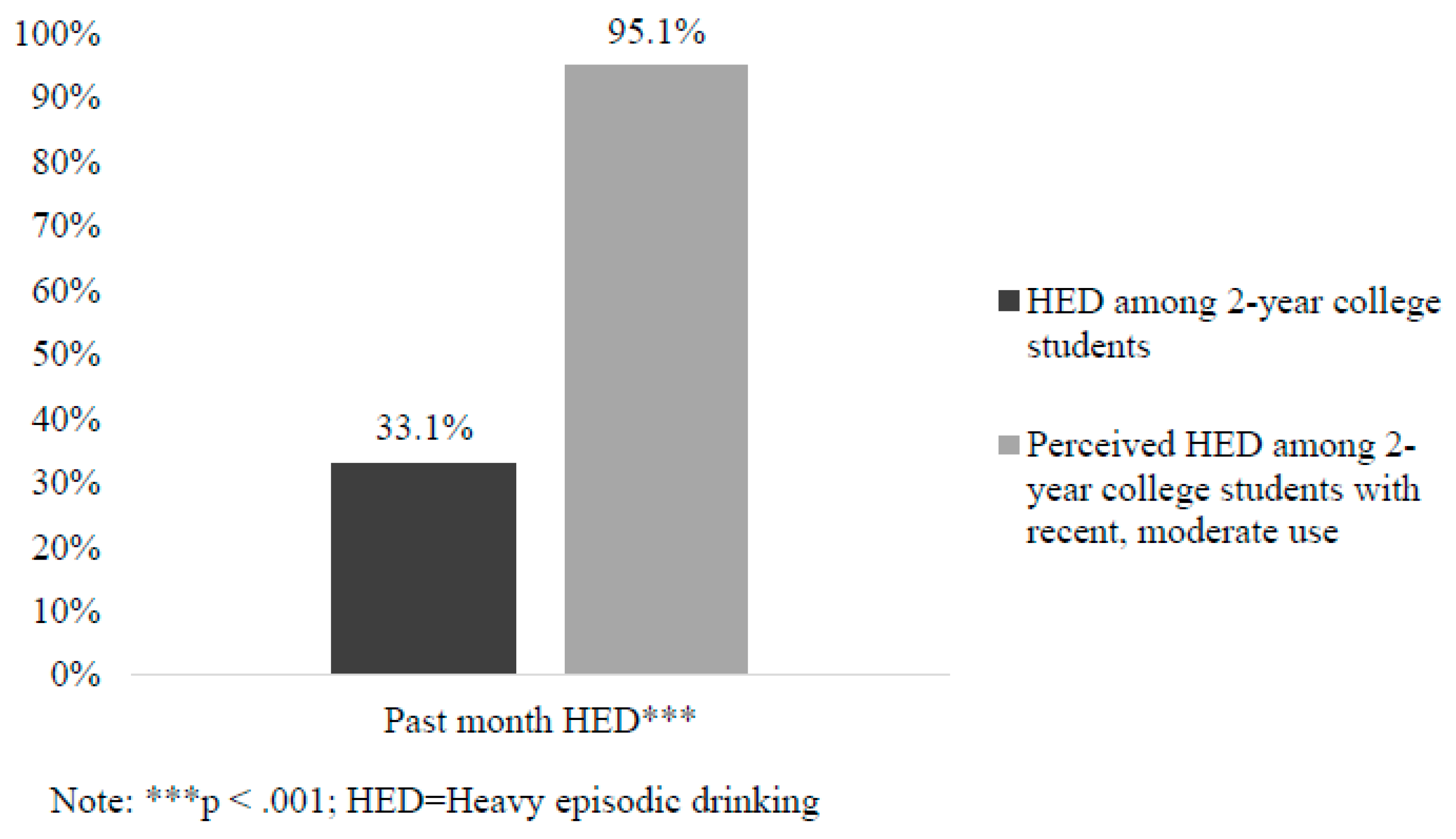

- Aim 2: To determine if 2-year college students who reported recent, moderate use overestimated peer alcohol and cannabis use, we conducted t-tests to examine differences in (1) drinks in a typical week as reported in the large, screening sample and perceived peer drinks per week as reported in the follow-up sample of those who reported recent, moderate use and (2) hours high in a typical week as reported in the screening sample and perceived peer hours high per week as reported in the follow-up sample. We also conducted chi-square tests to examine differences in the percent of 2-year students who engaged in past-month HED as reported in the screening sample and the perceived percent of 2-year students who engaged in HED in the past month as reported in the follow-up sample.

- Aim 3a: Using the follow-up sample of 2-year students who reported recent, moderate use and controlling for participant age and sex (0 = male, 1 = female), we examined associations between (1) perceived peer alcohol and cannabis use, and personal use and related consequences, and between (2) perceived peer approval of alcohol and cannabis use, and personal use and related consequences. Because all substance use outcomes were positively skewed, negative binomial regression models were used, and results are reported as rate ratios (RR), which represent the degree to which substance use outcomes change with a one-unit increase in the predictor.

- Aim 3b: We examined if identification with the reference group or student age moderated associations between perceived peer use and approval of use with personal use.

3. Results

3.1. Aim 1: Prevalence of Alcohol and Cannabis Use Among 2-Year College Students

3.2. Aim 2: Differences in Perceived Peer Alcohol and Cannabis Use and Personal Use

3.3. Aim 3: Associations Among Perceived Peer Descriptive and Injunctive Alcohol and Cannabis Norms, Personal Use, and Related Consequences

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Association of Community Colleges. (2002). Engaging the Nation’s community colleges as prevention partners. National Center for Higher Education. Available online: https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/sites/default/files/hec/product/community-colleges.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Baer, J. S. (1994). Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 8(1), 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, J. S., Stacy, A., & Larimer, M. (1991). Biases in the perception of drinking norms among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 52(6), 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambara, C. S., Harbour, C. P., Davies, T. G., & Athey, S. (2009). Delicate engagement: The lived experience of community college students enrolled in high-risk online courses. Community College Review, 36(3), 219–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, A. D. (2004). The social norms approach: Theory, research, and annotated bibliography. Available online: http://www.alanberkowitz.com/articles/social_norms.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Binger, K., Kerr, B. R., Lewis, M. A., Fairlie, A. M., Hyzer, R. H., & Moreno, M. A. (2023). Cannabis use among female community college students who use alcohol in a state with and a state without nonmedical cannabis legalization in the US. WMJ (Wisconsin Medical Journal), 122(2), 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Blowers, J. (2009). Common issues and collaborative solutions: A comparison of student alcohol use behaviors at the community college and four-year institutional levels. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 53(3), 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2003). Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64(3), 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsari, B., & Carey, K. B. (2001). Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13(4), 391–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadigan, J. M., Dworkin, E. R., Ramirez, J. J., & Lee, C. M. (2019). Patterns of alcohol use and marijuana use among students at 2- and 4-year institutions. Journal of American College Health, 67(4), 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiauzzi, E., Donovan, E., Black, R., Cooney, E., Buechner, A., & Wood, M. (2011). A survey of 100 community colleges on student substance use, programming, and collaborations. Journal of American College Health, 59(6), 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R. L., Parks, G. A., & Marlatt, G. A. (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremeens-Matthews, J., & Chaney, B. (2016). Patterns of alcohol use: A two-year college and four-year university comparison case study. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 40(1), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronce, J. M., Marchetti, M. A., Jones, M. B., & Ehlinger, P. P. (2022). A scoping review of brief alcohol interventions across young adult subpopulations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 36(6), 648–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronce, J. M., Toomey, T. L., Lenk, K., Nelson, T. F., Kilmer, J. R., & Larimer, M. E. (2018). NIAAA’s college alcohol intervention matrix: CollegeAIM. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 39(1), 43. [Google Scholar]

- DeJong, W. (2010). Social norms marketing campaigns to reduce campus alcohol problems. Health Communication, 25(6–7), 615–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotson, K. B., Dunn, M. E., & Bowers, C. A. (2015). Stand-alone personalized normative feedback for college student drinkers: A meta-analytic review. PLoS ONE, 10(10), e0139518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, J. C., Abdallah, D. A., Gilson, M. S., & Lee, C. M. (2024). Alcohol and marijuana use, consequences, and perceived descriptive norms: Differences between two- and four-year college students. Journal of American College Health, 72(3), 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, J. C., & Carey, K. B. (2012). Correcting exaggerated marijuana use norms among college abstainers: A preliminary test of a preventive intervention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(6), 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eren, C., & Keeton, A. (2015). Invisibility, difference, and disparity: Alcohol and substance abuse on two-year college campuses. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 39(12), 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graupensperger, S., Fleming, C. B., Jaffe, A. E., Rhew, I. C., Patrick, M. E., & Lee, C. M. (2021). Changes in young adults’ alcohol and marijuana use, norms, and motives from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(4), 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hingson, R., Zha, W., & Smyth, D. (2017). Magnitude and trends in heavy episodic drinking, alcohol-impaired driving, and alcohol-related mortality and overdose hospitalizations among emerging adults of college ages 18–24 in the United States, 1998–2014. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78(4), 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussong, A. M., Haik, A. K., & Loeb, H. M. (2023). Generation COVID: Young adult substance use. Current Opinion in Psychology, 52, 101640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juszkiewicz, J. (2017). Trends in community college enrollment and completion data, 2017. American Association of Community Colleges. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/165d304b-9003-4d98-b0e5-99f70f041f1d/content (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Kahler, C. W., Strong, D. R., & Read, J. P. (2005). Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 29(7), 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilmer, J. R., Walker, D. D., Lee, C. M., Palmer, R. S., Mallett, K. A., Fabiano, P., & Larimer, M. E. (2006). Misperceptions of college student marijuana use: Implications for prevention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67(2), 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaBrie, J. W., Hummer, J. F., Neighbors, C., & Larimer, M. E. (2010). Whose opinion matters? The relationship between injunctive norms and alcohol consequences in college students. Addictive Behaviors, 35(4), 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larimer, M. E., Lee, C. M., Kilmer, J. R., Fabiano, P. M., Stark, C. B., Geisner, I. M., Mallett, K. A., Lostutter, T. W., Cronce, J. M., Feeney, M., & Neighbors, C. (2007). Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(2), 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latané, B. (1981). The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36(4), 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. M., Kilmer, J. R., Neighbors, C., Atkins, D. C., Zheng, C., Walker, D. D., & Larimer, M. E. (2013). Indicated prevention for college student marijuana use: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(4), 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C. M., Kilmer, J. R., Neighbors, C., Cadigan, J. M., Fairlie, A. M., Patrick, M. E., Logan, D. E., Walter, T., & White, H. R. (2021). A Marijuana Consequences Checklist for young adults with implications for brief motivational intervention research. Prevention Science, 22(6), 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C. M., Neighbors, C., Kilmer, J. R., & Larimer, M. E. (2010). A brief, web-based personalized feedback selective intervention for college student marijuana use: A randomized clinical trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(2), 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, M. A., & Neighbors, C. (2006). Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health, 54(4), 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. A., Patrick, M. E., Litt, D. M., Atkins, D. C., Kim, T., Blayney, J. A., Norris, J., George, W. H., & Larimer, M. E. (2014). Randomized controlled trial of a web-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention to reduce alcohol-related risky sexual behavior among college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(3), 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., & Baum, S. (2016). Trends in community colleges: Enrollment, prices, student debt and completion. College Board Research Brief. Available online: http://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/trends-in-community-colleges-research-brief.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Moreira, M., Smith, L., & Foxcroft, D. (2009). Social norms interventions to reduce alcohol misuse in University or College students. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, C. M. (2012). Why access matters: The community college student body. American Association of Community Colleges. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED532204.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Napper, L. E., Kenney, S. R., Hummer, J. F., Fiorot, S., & LaBrie, J. W. (2016). Longitudinal relationships among perceived injunctive and descriptive norms and marijuana use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 77(3), 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). Characteristics of postsecondary students. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/csb/postsecondary-students (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Neighbors, C., LaBrie, J. W., Hummer, J. F., Lewis, M. A., Lee, C. M., Desai, S., Kilmer, J. R., & Larimer, M. E. (2010). Group identification as a moderator of the relationship between perceived social norms and alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(3), 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neighbors, C., Larimer, M. E., & Lewis, M. A. (2004). Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neighbors, C., Lee, C. M., Lewis, M. A., Fossos, N., & Larimer, M. E. (2007). Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(4), 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neighbors, C., Rodriguez, L. M., Rinker, D. V., Gonzales, R. G., Agana, M., Tackett, J. L., & Foster, D. W. (2015). Efficacy of personalized normative feedback as a brief intervention for college student gambling: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, F., Simons-Morton, B., Chaurasia, A., Luk, J., Haynie, D., & Liu, D. (2018). Post-high school changes in tobacco and cannabis use in the United States. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(1), 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H., Besecker, M., Huh, J., Zhou, S., Luczak, S. E., & Pedersen, E. R. (2022). Substance use descriptive norms and behaviors among US college students: Findings from the Healthy Minds Study. Epidemiologia, 3(1), 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orenstein, G. A., & Lewis, L. (2022). Eriksons stages of psychosocial development. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556096/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Patrick, M. E., Miech, R. A., Johnston, L. D., & O’Malley, P. M. (2024). Monitoring the future panel study annual report: National data on substance use among adults ages 19 to 65, 1976–2023. Monitoring the Future Monograph Series. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. Available online: https://monitoringthefuture.org/results/annual-reports/ (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Phua, J. J. (2013). The reference group perspective for smoking cessation: An examination of the influence of social norms and social identification with reference groups on smoking cessation self-efficacy. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(1), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M. B., Lange, J. E., Ketchie, J. M., & Clapp, J. D. (2007). The relationship between social identity, normative information, and college student drinking. Social Influence, 2(4), 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, N. R., Conner, B. T., Parnes, J. E., Prince, M. A., Shillington, A. M., & George, M. W. (2018). Marijuana eCHECKUPTO GO: Effects of a personalized feedback plus protective behavioral strategies intervention for heavy marijuana-using college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 190, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAS. (2014). Base SAS 9.4 procedures guide: Statistical procedures. SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg, J. E., & Maggs, J. L. (2002). A developmental perspective on alcohol use and heavy drinking during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement, 14, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, T. D., de Brey, C., & Dillow, S. (2019). Digest of education statistics, 2017. National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Staff, J., Schulenberg, J. E., Maslowsky, J., Bachman, J. G., O’Malley, P. M., Maggs, J. L., & Johnston, L. D. (2010). Substance use changes and social role transitions: Proximal developmental effects on ongoing trajectories from late adolescence through early adulthood. Development and Psychopathology, 22(4), 917–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez, C. E., Pasch, K. E., Laska, M. N., Lust, K., Story, M., & Ehlinger, E. P. (2011). Differential prevalence of alcohol use among 2-year and 4-year college students. Addictive Behaviors, 36(12), 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wall, A. F., BaileyShea, C., & McIntosh, S. (2012). Community college student alcohol use: Developing context-specific evidence and prevention approaches. Community College Review, 40(1), 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington State Board for Community and Technical Colleges [WSBCTC]. (2023). About us: Washington’s community and technical colleges. Available online: https://www.sbctc.edu (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Washington Student Achievement Council [WSAC]. (2023). Washington college grant. Available online: https://wsac.wa.gov (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- White, A. M., Hingson, R. W., Pan, I., & Yi, H. (2011). Hospitalizations for alcohol and drug overdoses in young adults ages 18–24 in the United States, 1999–2008: Results from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(5), 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X., & Savani, K. (2019). Descriptive norms for me, injunctive norms for you: Using norms to explain the risk gap. Judgment and Decision Making, 14(6), 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Screening Sample n = 1037 | Follow-Up Sample n = 246 | |

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) or n (%) | M (SD) or n (%) | |

| Age | 21.36 (2.99) | 21.69 (2.87) |

| 18–20 | 524 (50.50) | 99 (40.91) |

| 21–25 | 395 (38.10) | 118 (48.76 |

| 26–29 | 118 (11.40) | 25 (10.33) |

| Female | 650 (62.70) | 137 (55.69) |

| Race | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 16 (1.60) | 7 (2.97) |

| Asian | 134 (13.40) | 18 (7.63) |

| Asian American | 70 (7.00) | 7 (2.97) |

| Black/African American | 70 (7.00) | 11 (4.66) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 17 (1.70) | 8 (3.39) |

| White/Caucasian | 556 (55.80) | 155 (65.68) |

| Multiracial | 93 (9.30) | 19 (8.05) |

| Other | 41 (4.10) | 11 (4.66) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 185 (19.80) | 65 (28.76) |

| Alcohol outcomes | ||

| Alcohol use in past month | 549 (52.90) | 204 (83.30) |

| Drinks per week | 3.31 (7.76) | 5.5 (6.02) |

| HED in past month | 336 (33.10) | 143 (58.13) |

| Alcohol-related consequences a | -- | 5 (5.35) |

| Perceived peer alcohol use | ||

| Perceived peer drinks per week | -- | 10.24 (7.21) |

| Perceived peer HED in past month | -- | 233 (95.10) |

| Perceived peer approval of alcohol b | -- | 3.43 (1.11) |

| Cannabis outcomes | ||

| Cannabis use in past month | 369 (36.20) | 169 (68.98) |

| Days using cannabis | -- | 10.13 (11.66) |

| Hours high per week | 8.18 (20.95) | 14.2 (20.25) |

| Cannabis-related consequences c | -- | 13.9 (15.23) |

| Perceived peer cannabis use | ||

| Perceived peer hours high per week | -- | 13.33 (12.74) |

| Perceived peer approval of cannabis b | -- | 5.07 (1.14) |

| Identification with reference group d | -- | 1.84 (1.02) |

| Drinks per Week | Heavy Episodic Drinking (HED) | Alcohol-Related Consequences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate Ratio | (95% CI) | Odds Ratio | (95% CI) | Rate Ratio | (95% CI) | |

| Descriptive norms | n = 239 | n = 241 | n = 239 | |||

| Age | 1.05 | (1, 1.11) | 1.02 | (0.93, 1.12) | 1.03 | (0.97, 1.09) |

| Female | 0.72 * | (0.53, 0.97) | 0.67 | (0.39, 1.16) | 0.63 ** | (0.45, 0.88) |

| Perceived drinks per week | 1.03 ** | (1.01, 1.05) | -- | -- | 1.02 | (1, 1.04) |

| Perceived heavy episodic drinking | -- | -- | 15.93 ** | (1.99, 127.34) | -- | -- |

| Injunctive norms | n = 240 | n = 242 | n = 241 | |||

| Age | 1.06 * | (1, 1.11) | 1.02 | (0.94, 1.12) | 1.04 | (0.98, 1.1) |

| Female | 0.7 * | (0.51, 0.98) | 0.74 | (0.43, 1.29) | 0.76 | (0.53, 1.09) |

| Perceived approval of alcohol | 0.98 | (0.85, 1.14) | 1.1 | (0.87, 1.4) | 1.21 * | (1.04, 1.41) |

| Days Using Cannabis | Hours High per Week | Cannabis-Related Consequences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate Ratio | (95% CI) | Rate Ratio | (95% CI) | Rate Ratio | (95% CI) | |

| Descriptive norms | n = 236 | n = 230 | n = 227 | |||

| Age | 0.97 | (0.9, 1.04) | 1 | (0.93, 1.08) | 0.99 | (0.93, 1.07) |

| Female | 0.8 | (0.53, 1.2) | 0.81 | (0.51, 1.28) | 0.52 ** | (0.35, 0.79) |

| Perceived hours high per week | 1.01 | (0.99, 1.03) | 1.02 * | (1, 1.04) | 1.01 | (0.99, 1.03) |

| Injunctive norms | n = 239 | n = 231 | n = 228 | |||

| Age | 0.96 | (0.89, 1.03) | 1 | (0.93, 1.08) | 0.98 | (0.92, 1.06) |

| Female | 0.78 | (0.52, 1.17) | 0.79 | (0.5, 1.25) | 0.53 ** | (0.36, 0.8) |

| Perceived approval of cannabis | 1.15 | (0.95, 1.4) | 1.13 | (0.92, 1.39) | 1.09 | (0.9, 1.32) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duckworth, J.C.; Morrison, K.M.; Lee, C.M. Alcohol and Cannabis Perceived Descriptive and Injunctive Norms, Personal Use, and Consequences Among 2-Year College Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030251

Duckworth JC, Morrison KM, Lee CM. Alcohol and Cannabis Perceived Descriptive and Injunctive Norms, Personal Use, and Consequences Among 2-Year College Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(3):251. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030251

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuckworth, Jennifer C., Kristi M. Morrison, and Christine M. Lee. 2025. "Alcohol and Cannabis Perceived Descriptive and Injunctive Norms, Personal Use, and Consequences Among 2-Year College Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 3: 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030251

APA StyleDuckworth, J. C., Morrison, K. M., & Lee, C. M. (2025). Alcohol and Cannabis Perceived Descriptive and Injunctive Norms, Personal Use, and Consequences Among 2-Year College Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15030251