Contemporary Treatment of Crime Victims/Survivors: Barriers Faced by Minority Groups in Accessing and Utilizing Domestic Abuse Services †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Definitions and Prevalence

1.1.1. LGBTQIA+ Victims/Survivors

1.1.2. BME Victims/Survivors

1.1.3. Disabled Victims/Survivors

1.2. Accessing Support: Barriers for Different Communities

1.3. Purpose of the Current Research

- What do people think is good about the current DA support services, particularly in relation to fostering inclusion for LBGTQIA+, BME or disabled victims/survivors?

- How do people think DA support services for victims/survivors could be improved, particularly in relation to challenges for LBGTQIA+, BME or disabled people?

- Do LBGTQIA+, BME or disabled people have specific challenges and support needs?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surveys—General Public

2.2. Focus Group—Practitioners

2.3. Interviews—Victims/Survivors

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Analysis

2.5.1. Samples

2.5.2. Quantitative Analysis

2.5.3. Qualitative Analysis

3. Results

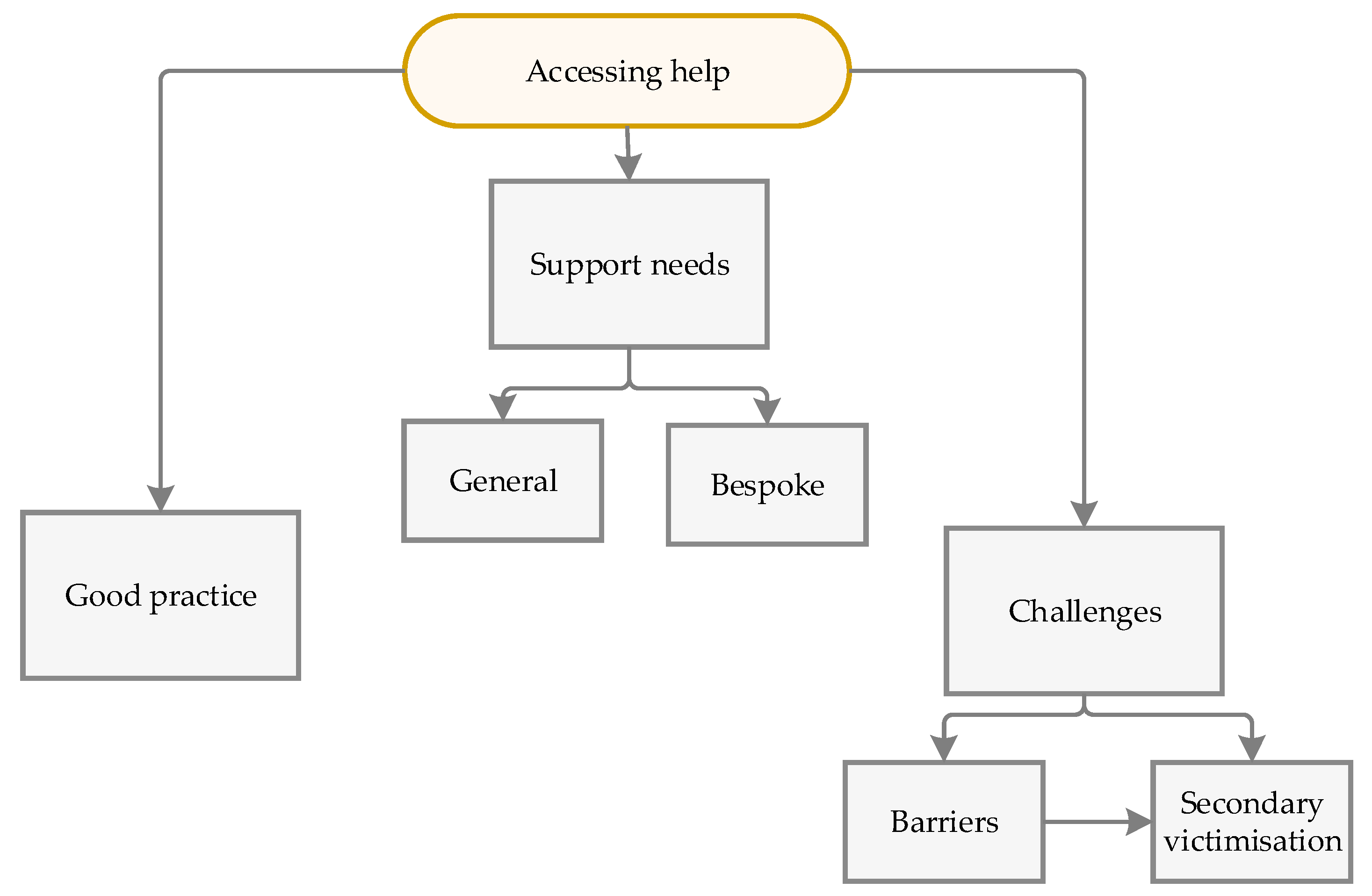

3.1. Identified Themes

3.1.1. Good Practice

“Without their support I would not have been able to leave, and I would likely not be alive”(Fleur, European)

“I think one of the shifts … to attempt as much as possible to keep people in their own home, that managing a move is not necessarily the best option”(Fay)

“I don’t have to mention to her, she already knows things… she also gave me a number for one of the Imam… even helped me with what sort of questions that I should be asking… That was that was really good”(Maya)

3.1.2. Secondary Victimization

“I was told by NHS officially: The abuse is too vile for them to handle”(Maria, black, British, heterosexual, non-disabled)

“I was not listened to… I was asked in front of my abuser every time to talk about what was happening”(Francis, white, British, heterosexual, non-disabled)

“They [police] said it’s a civil matter. But there’s violence involved… they could have nipped in the bud they could have stopped all this”(Rhea)

“I was bleeding… got no help… they said… you have to walk to the doctor which is so far away. I had no pushchair… I wasn’t allowed to call a taxi… can somebody get my car?... No, you’re not allowed to… they’re not making this any easier”(Rhea)

3.1.3. Barriers to Obtaining Support

“I did not recognise myself as a victim as I was not cowering in corners or being hit (well not regularly)”(Amelia, white, British, heterosexual, non-disabled)

“My abuser was considered everybody’s friend and a great dad. I was presented as the ’difficult’ one”(Ella, white, British, bisexual, disabled)

“Scared I wouldn’t be believed as the police dropped my case very quickly”(Miriam, white, British, bisexual, disabled)

“For many years my ex was able to use my diagnoses against me with [the] authorities… everything was justifiable on the grounds of concern for my mental health or parenting”(Freya, white, British, heterosexual, disabled)

“The fear of losing the children was a big problem and stopped me from telling social services the truth”(Sophia, white, British, heterosexual, disabled)

“I couldn’t afford to leave my ex…. Where would I go? The children were being manipulated … and I wasn’t prepared to leave them where this misinformation could continue”(Elsie, white, British, heterosexual, non-disabled)

“I hesitated to admit or seek support as I’m an Asian, so I had a lot to lose in society and community”(Amala, British, Bangladeshi, heterosexual, non-disabled)

“It was hard to get there, being a wheelchair user”(Evie, white, British, heterosexual, disabled)

“With physical disabilities… I relied on him for support, physically, mentally and financially”(Rosie, white, British, heterosexual, disabled)

“I don’t want to see 10 different people”(Rhea)

“I sometimes wonder if it would have been easier to stay”(Claudia, white, British, heterosexual, non-disabled)

“Too many satellite agencies and resources… how is a victim meant to know… which is the best one to turn to? Needs a nationally recognised and well publicised umbrella ‘face’ so that any person… knows exactly where to turn… an online triage process… who can help and a handholding online ‘advocate’”(Phoebe, white, English, heterosexual, non-disabled)

“thinking of taking the abuser back”(Nihal, Sri Lankan, heterosexual, non-disabled) or ending their life

“12 or 14 or 16 [sessions] most definitely are not… enough”(Enid, white, British, heterosexual, disabled)

“After a few months, it suddenly disappears and you are left alone in the ruins of your life”(Evelyn, white, British, bisexual, disabled)

“I was not given any instructions on what to do next”(Helvi, African, lesbian, non-disabled)

“care plan after… to prevent them returning to their abuser”(Charlotte, white, British, bisexual, disabled)

“A leaky roof’.. we are putting a bucket underneath the hole… catching as many as we can… trying to stop the place from flooding”(Louise)

3.1.4. Support Needs—General

“Sites where you had like chats where you can actually talk to people on the chat that helps massively”(Maya)

“An appointed advocate for each victim… would be hugely, hugely beneficial… we are already overwhelmed by just trying to survive”(Phoebe, white, English, heterosexual, non-disabled)

“There needs to be an organised step by step system of provision… mapped out and available for the person to move through at their own pace”(Sophia, white, British, heterosexual, disabled)

“Don’t use long words, or words shortened like DA … people in a distressed state struggle to process things anyway without jargon”(Iris, white, British, straight, non-disabled)

“They offered to find ways for me to be more comfortable and safe… drawing or listening to background music while we talked”(Isabel, white, British, heterosexual, disabled)

“The support workers… were the only ones who listened to me, believed me”(Maria, black, British, heterosexual, non-disabled)

“Why wasn’t there a [police] officer that had more understanding… had no idea and very, like… what’s happened tell us? There was no empathy… nothing to say… you’re protected… he cannot come back… you’re not alone… we’re here to help”(Rhea)

“My solicitor says to me, the best thing to do is look for a flat… how am I going to afford this? … they found this really horrible place… My kids will never come… no TV… so cold… my dad bought food… some duvets and blow-up mattresses”(Rhea)

3.1.5. Support Needs—Bespoke

BME

“Perhaps being given the opportunity to speak to someone from my own cultural background who could help support me as I lost every member of my family in the process of fleeing and have been culturally ostracised by my community”(Jasminder, British, Indian, disabled)

Disabled People

“Mental illness can make it… look like the victim is the perpetrator when police and people are underinformed about what mental illness and trauma look like”(Grace, white, English, ‘other’, disabled)

“The main thing I think would help is autism friendly shelter… quiet, self-contained, private places people can stay… Autistic people can’t be expected to live in ordinary shelters… it’s such a strain on an already overwhelmed sensory system”(Ella, white, British, bisexual, disabled)

LGBTQIA+

“They would have had a different experience of abuse as it is a different kind of relationship”(Ellie, British, French, bisexual, non-disabled)

“I think in same sex relationships it can be quite difficult as… this might affect traditional gender roles/identity such as male on male violence”(Freya, white, British, heterosexual, disabled)

“She [service provider] was also part of the LGBTQIA community and I think her lived experience allowed a deeper level of understanding”(Angela, white, British, lesbian, disabled)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Study

4.2. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ablaza, C., Kuskoff, E., Perales, F., & Parsell, C. (2022). Responding to domestic and family violence: The role of non-specialist services and implications for social work. The British Journal of Social Work, 53(1), 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afe, T. O., Emedoh, T. C., Ogunsemi, O. O., & Adegohun, A. A. (2017). Socio-demographic characteristics, partner characteristics, socioeconomic variables, and intimate partner violence in women with schizophrenia in south-south Nigeria. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 28(2), 707–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afrouz, R., Crisp, B. R., & Taket, A. (2018). Seeking help in domestic violence among Muslim women in Muslim-majority and non-Muslim-majority countries. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 21(3), 551–566. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, N., Couture-Carron, A., Alvi, S., & San Antonio, J. (2014). Experiences of Muslim and non-Muslim battered immigrant women with the police in the United States: A closer understanding of commonalities and differences. Violence Against Women, 19(12), 1449–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, N., Cockroft, A., Ansari, U., Omar, K., Ansari, N. M., Khan, A., & Chaudhry, U. U. (2009). Barriers to disclosing and reporting violence among women in Pakistan: Findings from a National Household Survey and Focus Group Discussions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(11), 1965–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, S. (2008). Neither safety nor justice: The UK government response to domestic violence against immigrant women. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 30(3), 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AVA. (2022). Staying mum A review of the literature on domestic abuse, mothering and child removal. AVA. [Google Scholar]

- Balderston, S. (2013). Victimized again? Intersectionality and injustice in disabled women’s lives after hate crime and rape. In M. Texler Segal, & V. Demos (Eds.), Gendered Perspectives on Conflict and Violence: Part A (Vol. 18A, pp. 17–51). Advances in Gender Research. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Bostock, J., Plumpton, M., & Pratt, R. (2009). Domestic violence against women: Understanding social processes and women’s experiences. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 19, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). National intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2010 summary report. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, N., Stokes, N., Retter, E., Manning, F., Curno, O., & Awoonor-Gordon, G. (2022). Blind and partially sighted people’s experiences of domestic abuse. Vision Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Couto, L., O’leary, N., & Brennan, I. (2023). Police victims of domestic abuse: Barriers to reporting victimisation. Policing and Society, 34(3), 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domestic Abuse Act. (2021). Domestic abuse act 2021. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2021/17/contents (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Ellsberg, M., Jansen, H. A., Heise, L., Watts, C. H., & Garcia-Moreno, C. (2008). Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence: An observational study. Lancet, 371(9619), 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, E., & Llewellyn, G. (2023). Exposure of women with and without disabilities to violence and discrimination: Evidence from cross-sectional national surveys in 29 middle-and low-income countries. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(11–12), 7215–7241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equality Act. (2010). Equality act 2010. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Fanslow, J. L., Malihi, Z. A., Hashemi, L., Gulliver, P. J., & McIntosh, T. K. D. (2021). Lifetime prevalence of intimate partner violence and disability: Results from a population-based study in New Zealand. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 61(3), 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, G., Agnew-Davies, R., Bailey, J., Howard, L., Howarth, E., Peters, T. J., Sardinha, L., & Feder, G. S. (2016). Domestic violence and mental health: A cross-sectional survey of women seeking help from domestic violence support services. Global Health Action, 9(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugate, M., Landis, L., Riordan, K., Naureckas, S., & Engel, B. (2005). Barriers to domestic violence help seeking: Implications for intervention. Violence Against Women, 11(3), 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graca, S. (2017). Domestic violence policy and legislation in the UK: A discussion of immigrant women’s vulnerabilities. European Journal of Current Legal Issues, 22, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, S., Allison, C., Kenny, R., Holt, R., Smith, P., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2019). The Vulnerability Experiences Quotient (VEQ): A study of vulnerability, mental health and life satisfaction in autistic adults. Autism Research, 12(10), 1516–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guasp, A. (2011). Lesbian, gay & bisexual people in later life. Stonewall. [Google Scholar]

- Hassouneh, D., & Glass, N. (2008). The influence of gender role stereotyping on women’s experiences of female same-sex intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women, 14(3), 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, J. C. (2021). An exposition of sexual violence as a method of disablist hate crime. In I. Zempi, & J. Smith (Eds.), Misogyny as hate crime (pp. 178–194). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heron, R. L., Eisma, M. C., & Browne, K. (2022). Barriers and facilitators of disclosing domestic violence to the UK health service. Journal of Family Violence, 37(3), 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home Office. (2024). New measures set out to combat violence against women and girls. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-measures-set-out-to-combat-violence-against-women-and-girls (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Jones, L., Wood, S., Bates, G., Eckley, L., McCoy, E., Mikton, C., Shakespeare, T., & Officer, A. (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: A systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulley, J., Bailey, L., Kirkman, G., Gibbs, G. R., Gomersall, T., Latif, A., & Jones, A. (2023). Intimate partner violence and barriers to help-seeking among black, Asian, minority ethnic and immigrant women: A qualitative metasynthesis of global research. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 24(2), 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interventions Alliance. (2021). Domestic abuse in black, Asian and minority ethnic groups | interventions alliance. Available online: https://interventionsalliance.com/domestic-abuse-in-black-asianand-minority-ethnic-groups/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Iob, E., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the UK during the COVID19 pandemic. British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(4), 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston-McCabe, P., Levi-Minzi, M., Van Hasselt, V. B., & Vanderbeek, A. (2011). Domestic violence and social support in a clinical sample of deaf and hard of hearing women. Journal of Family Violence, 26(1), 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N. (2012). Doing template analysis. In G. Symon, & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges (pp. 426–450). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek, K., McNeeley, M., & Collins, S. (2016). Young men who have sex with men’s experiences with intimate partner violence. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(2), 143–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magowan, P. (2003). Nowhere to run, nowhere to hide: Domestic violence and disabled women. Safe: Domestic Abuse Quarterly, 5, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, S., O’Brien, R., & Stenhouse, R. (2022). Experiences of Scottish men who have been subject to intimate partner violence in same sex relationships. New Jersey Institute of Technology. Available online: https://www.waverleycare.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/GBM_RR_summary.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- McDowell, M. J., Hughto, J. M., & Reisner, S. L. (2019). Risk and protective factors for mental health morbidity in a community sample of female-to-male trans-masculine adults. BMC Psychiatry, 19, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2022). Characteristics of victims of domestic abuse based on findings from the crime survey for England and Wales and police recorded crime. Office of National Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2023). Domestic abuse victim characteristics, England and Wales: Year ending March 2023. Office of National Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Olabanji, O. A. (2022). Collaborative approaches to addressing domestic and sexual violence among black and minority ethnic communities in Southampton: A case study of yellow door. Societies, 12(6), 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitzmeier, S. M., Malik, M., Kattari, S. K., Marrow, E., Stephenson, R., Agénor, M., & Reisner, S. L. (2020). Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and correlates. American Journal of Public Health, 110(9), E1–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettitt, B., Greenhead, S., Khalifeh, H., Drennan, V., Hart, T., Hogg, J., Borschmann, R., Mamo, E., & Moran, P. (2013). At risk, yet dismissed: The criminal victimisation of people with mental health problems. Victim Support & Mind. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Sánchez, M., Skowronski, M., Bohner, G., & Megías, J. L. (2021). Talking about ‘victims’, ‘survivors’ and ‘battered women’: How labels affect the perception of women who have experienced intimate partner violence. Revista de Psicologia Social, 36(1), 30–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SafeLives. (2015). Getting it right the first time. SafeLives. [Google Scholar]

- SafeLives. (2017). Your choice: ‘Honour’-based violence, forced marriage and domestic abuse. SafeLives. [Google Scholar]

- Scheer, J. R., Lawlace, M., Cascalheira, C. J., Newcomb, M. E., & Whitton, S. W. (2023). Help-seeking for severe intimate partner violence among sexual and gender minority adolescents and young adults assigned female at birth: A latent class analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(9–10), 6723–6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, C. H. (2015). Hate crime against people with disabilities. In N. Hall, A. Corb, P. Giannasi, & J. G. D. Grieve (Eds.), The routledge international handbook on hate crime (pp. 193–206). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Southampton Census. (2021). Available online: https://data.southampton.gov.uk/population/census-2021/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Stephenson, R., Darbes, L. A., Rosso, M. T., Washington, C., Hightow-Weidman, L., Sullivan, P., & Gamarel, K. E. (2022). Perceptions of contexts of intimate partner violence among young, partnered gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(15–16), NP12881–NP12900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiara, R. K., & Hague, G. (2013). Disabled women and domestic violence: Increased risk but fewer services. In A. Roulstone, & H. Mason-Bish (Eds.), Disability, hate crime and violence (pp. 106–117). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2018). Violence against women Prevalence Estimates, 2018. Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. M., Fauci, J. E., & Goodman, L. A. (2015). Bringing trauma-informed practice to domestic violence programs: A qualitative analysis of current approaches. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(6), 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. of Participants | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Simplified Ethnic Group (n = 303) | ||

| Not BME | 241 | 79.5 |

| BME | 33 | 10.9 |

| Unclear | 29 | 9.6 |

| Gender (n = 317) | ||

| Female | 245 | 77.3 |

| Male | 24 | 7.6 |

| Transgender | 4 | 1.3 |

| Non-binary | 9 | 2.8 |

| Queer | 3 | 0.9 |

| Asexual | 1 | 0.3 |

| Other (nonbinary, transgender, transmasculine, and gender queer) | 1 | 0.3 |

| Did not answer | 30 | 9.5 |

| Sexual Orientation (n = 317) | ||

| Straight/Heterosexual | 219 | 69.1 |

| Bisexual | 62 | 19.6 |

| Lesbian | 7 | 2.2 |

| Pansexual | 6 | 1.9 |

| Gay | 5 | 1.6 |

| Asexual | 3 | 0.9 |

| Other | 3 | 0.9 |

| Queer | 2 | 0.6 |

| Chose not to answer | 10 | 3.2 |

| Disability (n = 170) | ||

| Mental Illness, Nervous Disorder | 147 | 86.5 |

| Mobility Impairment | 48 | 28.2 |

| Autism | 47 | 27.6 |

| Other Disability | 24 | 14.1 |

| Specific Learning Difficulty | 21 | 12.4 |

| Deafness (Hearing Impairment) | 15 | 8.8 |

| Fibromyalgia | 10 | 5.9 |

| ADHD | 9 | 5.3 |

| Blindness (Visual Impairment) | 6 | 3.5 |

| Range of Services Accessed (n = 317) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Counselling | 163 | 51.4 |

| Mental Health | 130 | 41.0 |

| How to remain safe | 113 | 35.6 |

| Advocacy | 110 | 34.7 |

| How to leave | 64 | 20.2 |

| Children | 61 | 19.2 |

| Legal Advice | 59 | 18.6 |

| Reporting an offence | 57 | 18.0 |

| Housing | 45 | 14.2 |

| Physical Harm | 37 | 11.7 |

| Finances | 17 | 5.4 |

| Other | 6 | 1.2 |

| Barriers to Accessing Support | No. of Yes Responses (n = 160) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Embarrassment or shame | 109 | 68.1 |

| Not recognizing abuse | 107 | 66.8 |

| Fear of what might happen | 105 | 65.6 |

| Fear of not being believed | 101 | 63.1 |

| Denial | 90 | 56.3 |

| Not a big deal | 70 | 43.8 |

| Hope things will change | 64 | 40.0 |

| Worry about information sharing | 63 | 39.4 |

| Love for abuser | 52 | 32.5 |

| Loyalty for abuser | 50 | 31.3 |

| Accessing support | 50 | 31.3 |

| Worry about losing access to children | 49 | 30.6 |

| Worry about finances | 46 | 28.8 |

| Worry about losing friends and family | 46 | 28.8 |

| Worry about housing | 41 | 25.6 |

| Other | 16 | 10.0 |

| Required Services | No. of Participants (n = 317) | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Support: Mental Health | 217 | 68.5 |

| Counselling | 214 | 67.5 |

| How to remain safe | 211 | 66.6 |

| Advocacy | 201 | 63.4 |

| How to leave a partner/abuser | 197 | 62.1 |

| Reporting an offence | 192 | 60.6 |

| Legal advice | 191 | 60.3 |

| Housing/access to refuge | 188 | 59.3 |

| Medical Support: Physical Harm | 186 | 58.6 |

| Finances/Money | 181 | 57.1 |

| Your children/dependents | 180 | 56.8 |

| Other | 16 | 5.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cole, T.; Harvey, O.; Healy, J.C.; Smith, C. Contemporary Treatment of Crime Victims/Survivors: Barriers Faced by Minority Groups in Accessing and Utilizing Domestic Abuse Services. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020103

Cole T, Harvey O, Healy JC, Smith C. Contemporary Treatment of Crime Victims/Survivors: Barriers Faced by Minority Groups in Accessing and Utilizing Domestic Abuse Services. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(2):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020103

Chicago/Turabian StyleCole, Terri, Orlanda Harvey, Jane C. Healy, and Chloe Smith. 2025. "Contemporary Treatment of Crime Victims/Survivors: Barriers Faced by Minority Groups in Accessing and Utilizing Domestic Abuse Services" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 2: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020103

APA StyleCole, T., Harvey, O., Healy, J. C., & Smith, C. (2025). Contemporary Treatment of Crime Victims/Survivors: Barriers Faced by Minority Groups in Accessing and Utilizing Domestic Abuse Services. Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15020103