Frames of Reference Collectively Organize Space to Influence Attentional Allocation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment 1

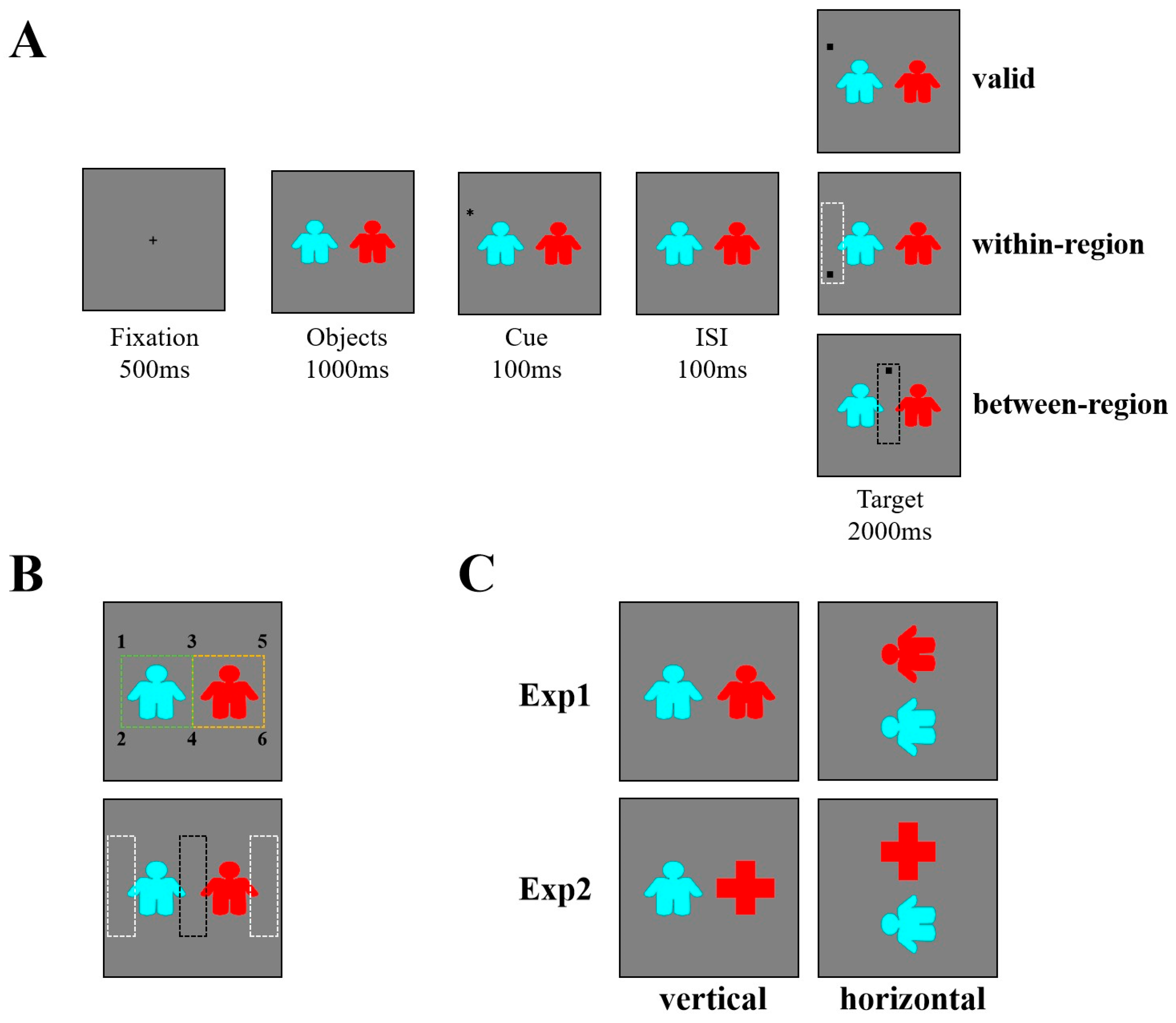

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Apparatus and Stimuli

2.1.3. Procedure and Design

2.1.4. Statistical Analysis

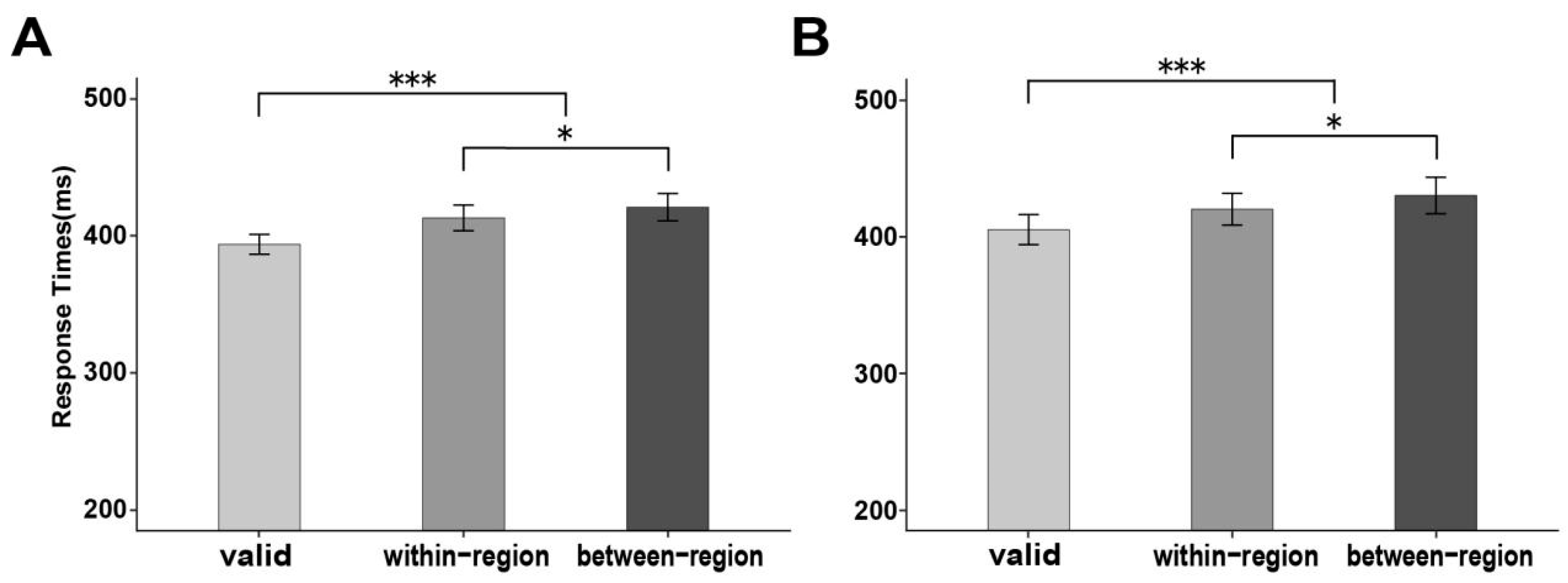

2.2. Results

2.3. Discussion

3. Experiment 2

3.1. Methods

3.2. Results

3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Janabi, S., & Greenberg, A. S. (2016). Target–object integration, attention distribution, and object orientation interactively modulate object-based selection. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 78(7), 1968–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrahami, J. (1999). Objects of attention, objects of perception. Perception & Psychophysics, 61(8), 1604–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barnas, A. J., & Greenberg, A. S. (2019). Object-based attention shifts are driven by target location, not object placement. Visual Cognition, 27(9–10), 768–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L. A., & Van Deman, S. R. (2008). Inhibition within a reference frame during the interpretation of spatial language. Cognition, 106(1), 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, M. (2011). Visual attention: The past 25 years. Vision Research, 51(13), 1484–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., Weidner, R., Weiss, P. H., Marshall, J. C., & Fink, G. R. (2012). Neural interaction between spatial domain and spatial reference frame in parietal–occipital junction. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(11), 2223–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z. (2012). Object-based attention: A tutorial review. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 74(5), 784–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driver, J., & Baylis, G. C. (1989). Movement and visual attention: The spotlight metaphor breaks down. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception & Performance, 15(3), 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- Egly, R., Driver, J., & Rafal, R. D. (1994). Shifting visual attention between objects and locations: Evidence from normal and parietal lesion subjects. Journal of Experimental Psychology General, 123(2), 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halligan, P. W., Fink, G. R., Marshall, J. C., & Vallar, G. (2003). Spatial cognition: Evidence from visual neglect. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(3), 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirtle, S. C., & Jonides, J. (1985). Evidence of hierarchies in cognitive maps. Memory & Cognition, 13(3), 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingworth, A., Maxcey-Richard, A. M., & Vecera, S. P. (2012). The spatial distribution of attention within and across objects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 38(1), 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, D., Stein, T., & Peelen, M. V. (2014). Object grouping based on real-world regularities facilitates perception by reducing competitive interactions in visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(30), 11217–11222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, D. J., & Behrmann, M. (2008). The space of an object: Object attention alters the spatial gradient in the surround. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 34(2), 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, D. J., & Behrmann, M. (2011). Space-, object-, and feature-based attention interact to organize visual scenes. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 73(8), 2434–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengyel, G., Nagy, M., & Fiser, J. (2021). Statistically defined visual chunks engage object-based attention. Nature Communications, 12(1), 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinson, S. C. (2004). Space in language and cognition: Explorations in cognitive diversity (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Logan, G. D. (2008). Object-based attention in Chinese readers of Chinese words: Beyond Gestalt principles. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15(5), 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, A., Lupiáñez, J., & Casagrande, M. (2012). Investigating hemispheric lateralization of reflexive attention to gaze and arrow cues. Brain and Cognition, 80(3), 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, T. P., & Pellegrino, J. W. (1993). Chapter 3 psychological perspectives on spatial cognition thomas. In T. Gärling, & R. G. Golledge (Eds.), Advances in psychology (Vol. 96, pp. 47–82). North-Holland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, W., Li, Q., Sun, Y., Wang, H., & Liu, X. (2016). Conflict processing among multiple frames of reference. PsyCh Journal, 5(4), 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, N. S., & Huttenlocher, J. (2000). Making space: The development of spatial representation and reasoning. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, K. S., Roggeveen, A. B., Creighton, S. E., Bennett, P. J., & Sekuler, A. B. (2012). How prevalent is object-based attention? PLoS ONE, 7(2), e30693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, S., & Kawahara, J. I. (2015). Attentional capture by completely task-irrelevant faces. Psychological Research, 79(4), 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, B. J. (2001). Objects and attention: The state of the art. Cognition, 80(1–2), 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E. A., Husband, H. L., Yee, K., Fullerton, A., & Jakobsen, K. V. (2014). Visual search efficiency is greater for human faces compared to animal faces. Experimental Psychology, 61(6), 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F., Zhou, S., Gao, Y., Hu, S., Zhang, T., Kong, F., & Zhao, J. (2021). Are you looking at me? Impact of eye contact on object-based attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 47(6), 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., & Wang, H. (2010). Perception of space by multiple intrinsic frames of reference. PLoS ONE, 5(5), e10442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamborello, F. P., Sun, Y., & Wang, H. (2012). Spatial reasoning with multiple intrinsic frames of reference. Experimental Psychology, 59(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasi, L., & Laeng, B. (2012). Psychology of spatial cognition. WIREs Cognitive Science, 3(6), 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, B. (2000). Remembering spaces. In E. Tulving, & F. I. M. Craik (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of memory (pp. 363–378). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, B. (2003). Structures of mental spaces: How people think about space. Environment and Behavior, 35(1), 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecera, S. P., & Farah, M. J. (1994). Does visual attention select objects or locations? Journal of Experimental Psychology General, 123(2), 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J., Xu, H., Duan, J., & Shen, M. (2018). Object-based attention on social units: Visual selection of hands performing a social interaction. Psychological Science, 29(7), 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J., & Fu, S. (2014). Attention can operate on semantic objects defined by individual Chinese characters. Visual Cognition, 22(6), 770–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Nan, W. Frames of Reference Collectively Organize Space to Influence Attentional Allocation. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1713. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121713

Liu Y, Nan W. Frames of Reference Collectively Organize Space to Influence Attentional Allocation. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1713. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121713

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yaohong, and Weizhi Nan. 2025. "Frames of Reference Collectively Organize Space to Influence Attentional Allocation" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1713. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121713

APA StyleLiu, Y., & Nan, W. (2025). Frames of Reference Collectively Organize Space to Influence Attentional Allocation. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1713. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121713