The Organizational Halo: How Perceived Philanthropy Awareness Curbs Abusive Supervision via Moral Pride

Abstract

1. Introduction

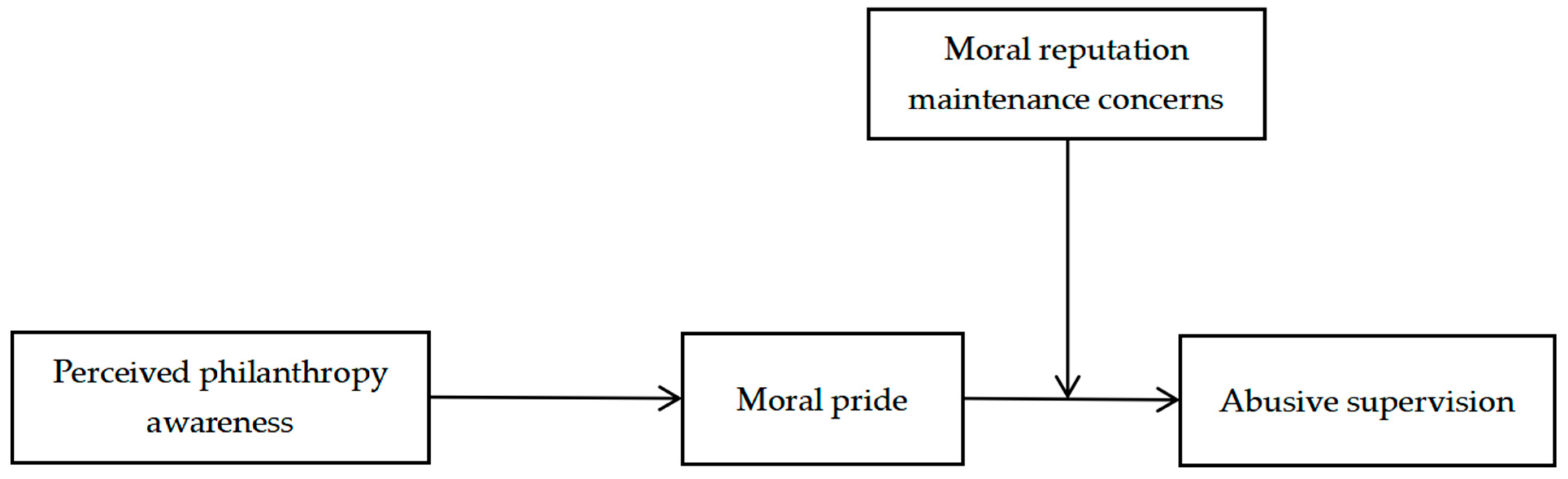

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theoretical Background: Affective Events Theory

2.2. Affective Events Theory and Philanthropy Awareness

2.3. The Mediating Role of Moral Pride

2.4. The Moderating Role of Moral Reputation Maintenance Concerns

3. Method

3.1. Study Procedure and Participants

3.2. Measurements

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Validation

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Simple Correlations

4.3. Mediation Effect Analysis

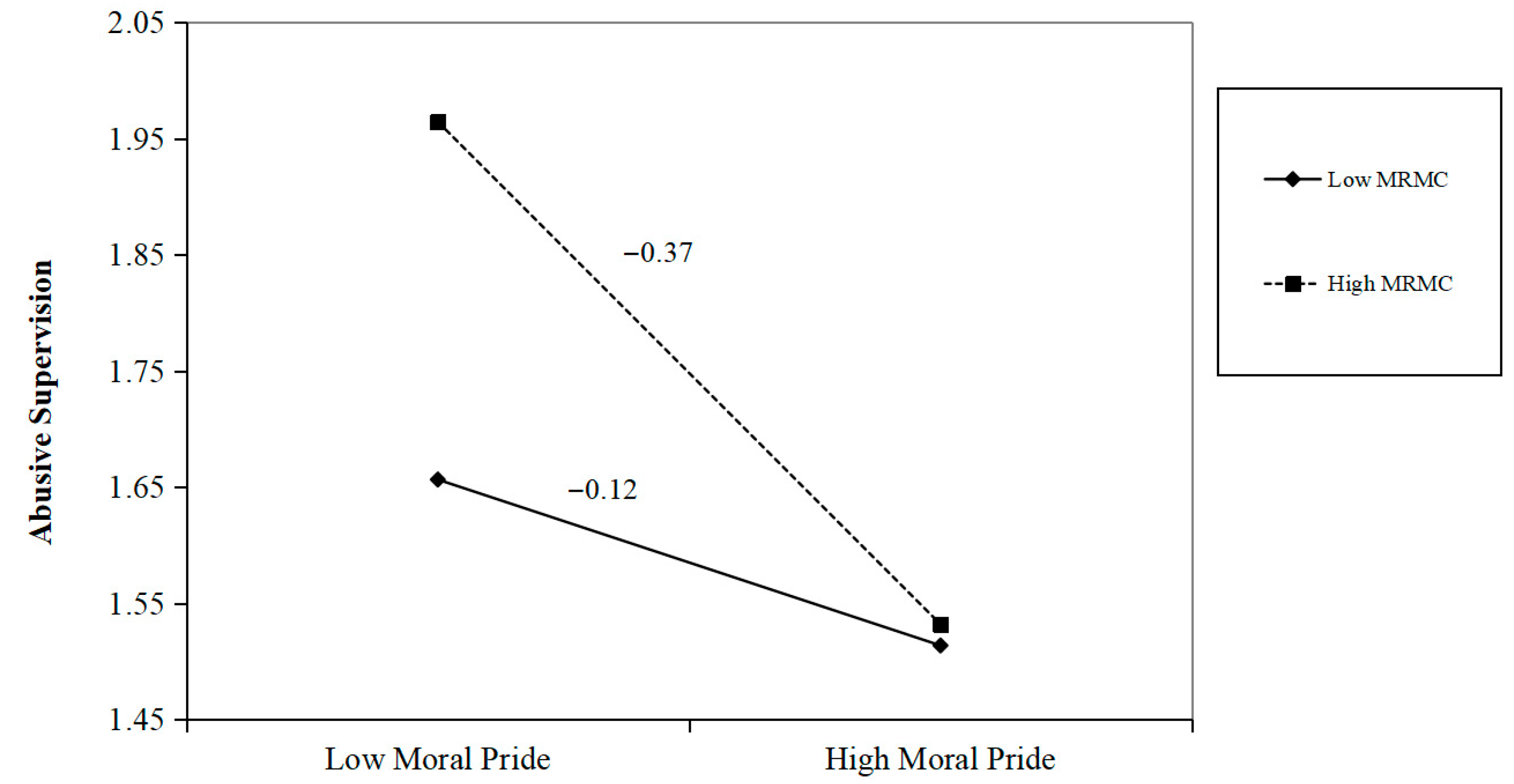

4.4. Moderation Effect Analysis

4.5. Moderated Mediation Effect Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Perceived philanthropy awareness (Walker & Kent, 2013):

- I know of the good things my company does for the community.

- It pleases me to know that my company is a charitable organization.

- I am aware of the philanthropy of my company.

- Moral pride (Boezeman & Ellemers, 2007):

- I feel good when people describe me as a moral person.

- I am proud of being moral.

- I am proud to be a person with a sense of morality.

- Moral reputation maintenance concerns (Baer et al., 2015):

- I’m concerned about maintaining my image.

- I worry about protecting my reputation.

- I feel the need to preserve the opinion others have of me.

- I’m pre-occupied with keeping others’ views of my character intact.

- Abusive supervision (Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007):

- I ridicule my subordinates.

- I tell my subordinate his/her thoughts or feelings are stupid.

- I put one of my subordinates down in front of others.

- I make negative comments about my subordinates to others.

- I tell my subordinate he/she is incompetent.

- Social desirability (Strahan & Gerbasi, 1972)

- I never hesitate to go out of my way to help someone in trouble.

- I have never intensely disliked anyone.

- When I don’t know something I don’t at all mind admitting it.

- I am always courteous, even to people who are disagreeable.

- I would never think of letting someone else be punished for my wrong doings.

- I sometimes feel resentful when I don’t get my way. (R)

- There have been times when I felt like rebelling against people in authority even though I knew they were right. (R)

- I can remember “playing sick” to get out of something. (R)

- There have been times when I was quite jealous of the good fortune of others. (R)

- I am sometimes irritated by people who ask favors of me. (R)

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Aust, F., Diedenhofen, B., Ullrich, S., & Musch, J. (2013). Seriousness checks are useful to improve data validity in online research. Behavior Research Methods, 45(2), 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, M. D., Dhensa-Kahlon, R. K., Colquitt, J. A., Rodell, J. B., Outlaw, R., & Long, D. M. (2015). Uneasy lies the head that bears the trust: The effects of feeling trusted on emotional exhaustion. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), 1637–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barden, J., Rucker, D. D., & Petty, R. E. (2005). “Saying One Thing and Doing Another”: Examining the impact of event order on hypocrisy judgments of others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(11), 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, C. M., Lucianetti, L., Bhave, D. P., & Christian, M. S. (2015). “You wouldn’t like me when I’m sleepy”: Leaders’ sleep, daily abusive supervision, and work unit engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 58(5), 1419–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, E. S., Glavas, A., Mannor, M. J., & Erskine, L. (2017). Business for good? An investigation into the strategies firms use to maximize the impact of financial corporate philanthropy on employee attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 146(1), 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boezeman, E. J., & Ellemers, N. (2007). Volunteering for charity: Pride, respect, and the commitment of volunteers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazza, N., Guidetti, M., & Pagliaro, S. (2015). Who cares for reputation? Individual differences and concern for reputation. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 34(1), 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, W., & Rajadhyaksha, U. (2021). What do we know about corporate philanthropy? A review and research directions. Business Ethics, the Environment & Responsibility, 30(3), 262–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, C. I. C., & Chen, Z. (2014). Beyond the individual victim: Multilevel consequences of abusive supervision in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1074–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, A., & Pache, A.-C. (2015). Research on corporate philanthropy: A review and assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(3), 343–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, P. (2010). Social Desirability Bias. In J. Sheth, & N. Malhotra (Eds.), Wiley international encyclopedia of marketing. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, R. F., Wang, X., & Abbott, J. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and individual outcomes: The mediating role of gratitude and compassion at work. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62(3), 332–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- He, W., Li, C., & Shen, R. (2025). Transcendent leadership and corporate philanthropic disaster response. Chinese Management Studies. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoobler, J. M., & Hu, J. (2013). A model of injustice, abusive supervision, and negative affect. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. J., Kim, D., & Lanaj, K. (2024). The benefits of reflecting on gratitude received at home for leaders at work: Insights from three field experiments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(9), 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Carnevale, J. B., Mackey, J., Paterson, T. A., Li, X., & Yang, D. (2025). Fulfilling moral duty or prioritizing moral image? The moral self-regulatory consequences of ethical voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 110(1), 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M., Ju, D., Yam, K. C., Liu, S., Qin, X., & Tian, G. (2023). Employee humor can shield them from abusive supervision: JBE. Journal of Business Ethics, 186(2), 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z., Hu, X., & Wang, Z. (2018). Career adaptability and plateaus: The moderating effects of tenure and job self-efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 104, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, D., Huang, M., Liu, D., Qin, X., Hu, Q., & Chen, C. (2019). Supervisory consequences of abusive supervision: An investigation of sense of power, managerial self-efficacy, and task-oriented leadership behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 154, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng-Highberger, F., Feng, Z., Yam, K. C., Chen, X. P., & Li, H. (2024). Middle power plays: How and when Mach middle managers use downward abuse and upward guanxi to gain and maintain power. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(7), 1088–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R., Lee, M., Lee, H.-T., & Kim, N.-M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and employee-company identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(4), 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Cognition and motivation in emotion. The American Psychologist, 46(4), 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-Y., Hur, Y., & Sung, M. (2015). Happy to support: Emotion as a mediator in brand building through philanthropic corporate sponsorship. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 43(6), 977–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B. N., Xing, L., Zhang, R., Fu, X., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Different forms of corporate philanthropy, different effects: A multilevel analysis. Business Ethics: A European Review, 29(4), 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J. D., Frieder, R. E., Brees, J. R., & Martinko, M. J. (2017). Abusive supervision: A meta-analysis and empirical review. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1940–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M., Alaghbari, M. A., Beshr, B., & Al-Ghazali, B. M. (2023). Perceived CSR on career satisfaction: A moderated mediation model of cultural orientation (collectivism and masculinity) and organisational pride. Sustainability, 15(6), 5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascolo, M. F., & Fischer, K. W. (1995). Developmental transformations in appraisals for pride, shame, and guilt. In J. P. Tangney, & K. W. Fischer (Eds.), Self-conscious emotions: The psychology of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride (pp. 64–113). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, J. E., & Chen, G. (2011). The etiology of the multilevel paradigm in management research. Journal of Management, 37(2), 610–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawritz, M. B., Greenbaum, R. L., Butts, M. M., & Graham, K. A. (2017). I just can’t control myself: A self-regulation perspective on the abuse of deviant employees. Academy of Management Journal, 60(4), 1482–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, A. C., Effron, D. A., & Monin, B. (2010). Moral self-licensing: When being good frees us to be bad. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(5), 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S. (2009). Pride and gratitude: How positive emotions influence the prosocial behaviors of organizational leaders. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 15(4), 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A., Round, H., Bhattacharya, S., & Roy, A. (2017). Ethical climates in organizations: A review and research agenda. Business Ethics Quarterly, 27(4), 475–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. W. H., Yam, K. C., & Aguinis, H. (2019). Employee perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Effects on pride, embeddedness, and turnover. Personnel Psychology, 72(1), 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, E. H., Jr., Forsyth, D. R., Banks, G. C., & McDaniel, M. A. (2012). A meta-analysis of the Dark Triad and work behavior: A social exchange perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 557–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palan, S., & Schitter, C. (2018). Prolific.ac—A subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 17, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.-Y., & Lin, K. J. (2016). Who suffers when supervisors are unhappy? The roles of leader-member exchange and abusive supervision. Journal of Business Ethics, 151, 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., & Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priesemuth, M., Schminke, M., Ambrose, M. L., & Folger, R. (2014). Abusive supervision climate: A multiple-mediation model of its impact on group outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1513–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X., Huang, M., Johnson, R. E., Hu, Q., & Ju, D. (2018). The short-lived benefits of abusive supervisory behavior for actors: An investigation of recovery and work engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 61(5), 1951–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, S., Iliev, R., & Medin, D. L. (2009). Sinning saints and saintly sinners: The paradox of moral self-regulation. Psychological Science, 20(4), 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, S., Wisse, B., Van Yperen, N. W., & Rus, D. (2018). On ethically solvent leaders: The roles of pride and moral identity in predicting leader ethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(3), 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S. D., Cunningham, P., Diehl, S., & Terlutter, R. (2024). Employees’ positive perceptions of corporate social responsibility create beneficial outcomes for firms and their employees: Organizational pride as a mediator. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(3), 2574–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano Archimi, C., Reynaud, E., Yasin, H. M., & Bhatti, Z. A. (2018). How perceived corporate social responsibility affects employee cynicism: The mediating role of organizational trust. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(4), 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahan, R., & Gerbasi, K. C. (1972). Short, homogeneous versions of the Marlow-Crowne social desirability scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28(2), 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33(3), 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B. J., Simon, L., & Park, H. M. (2017). Abusive supervision. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonasch, A. J., Reynolds, T., Winegard, B. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2018). Death before dishonor: Incurring costs to protect moral reputation. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(5), 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M., & Kent, A. (2013). The roles of credibility and social consciousness in the corporate philanthropy-consumer behavior relationship. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(2), 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zhou, M., Zhu, H., & Wu, X. (2023). The impact of abusive supervision differentiation on team performance in team competitive climates. Personnel Review, 52(4), 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective Events Theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In B. M. Staw, & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (Vol. 18, pp. 1–74). Elsevier Science/JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L. A., & DeSteno, D. (2008). Pride and perseverance: The motivational role of pride. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(6), 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisse, B., & Sleebos, E. (2016). When the dark ones gain power: Perceived position power strengthens the effect of supervisor Machiavellianism on abusive supervision in a work setting. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. Available online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1760318. [CrossRef]

| Continent | N (Frequency) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 208 | 47.93 |

| Asia | 8 | 1.84 |

| Europe | 147 | 33.87 |

| North America | 61 | 14.06 |

| Oceania | 5 | 1.15 |

| South America | 5 | 1.15 |

| Total | 434 | 100% |

| Characteristic | Category | N (Frequency) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 219 | 50.5 |

| Female | 215 | 49.5 | |

| Age (Years) | 19–30 | 166 | 38.2 |

| 31–45 | 173 | 39.9 | |

| 46–60 | 74 | 17.1 | |

| ≥61 | 21 | 4.8 | |

| Education | High school diploma and below | 42 | 9.7 |

| Associate’s degree | 18 | 4.1 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 211 | 48.6 | |

| Master’s degree | 129 | 29.7 | |

| Doctoral degree | 34 | 7.8 | |

| Tenure (Years) | 0–3 | 134 | 30.9 |

| 4–10 | 207 | 47.7 | |

| ≥11 | 93 | 21.4 |

| Model | χ2 | df | p | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | ECVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesized four-factor model | 229.11 | 84.00 | — | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.69 |

| Three-factor model (PPA + MP, AS, MRMC) | 896.27 | 87.00 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 2.22 |

| Two-factor model (PPA + MP + MRMC, AS) | 1603.63 | 89.00 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 3.84 |

| One-factor model | 2778.45 | 90.00 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 6.54 |

| Variable | CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PPA | 0.89 | 0.72 | (0.85) | |||

| 2. MP | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.35 *** | (0.84) | ||

| 3. MRMC | 0.85 | 0.59 | 0.15 ** | 0.31 *** | (0.77) | |

| 4. AS | 0.88 | 0.60 | −0.07 | −0.21 | 0.10 | (0.77) |

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.50 | 0.50 | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 36.57 | 11.95 | −0.01 | |||||||

| 3. Education | 3.22 | 1.00 | 0.12 * | 0.01 | ||||||

| 4. Organizational tenure | 7.27 | 6.11 | −0.03 | 0.62 ** | 0.00 | |||||

| 5. Social desirability | 4.94 | 1.03 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.12 * | 0.05 | ||||

| 6. Perceived philanthropy awareness | 3.90 | 0.90 | 0.19 *** | −0.10 * | 0.10 * | −0.03 | 0.33 *** | |||

| 7. Moral pride | 4.42 | 0.59 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.27 *** | 0.31 *** | ||

| 8. Moral reputation maintenance concerns | 3.41 | 1.01 | 0.12 ** | −0.09 * | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.14 ** | 0.28 *** | |

| 9. Abusive supervision | 1.30 | 0.52 | 0.07 | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.19 *** | −0.09 | −0.21 *** | 0.11 * |

| Moral Pride | Abusive Supervision | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

| b | S.E. | t | b | S.E. | t | b | S.E. | t | b | S.E. | t | |

| Gender | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.90 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 1.99 * | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.69 |

| Age | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −1.20 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −1.22 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −1.11 |

| Education | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.52 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.42 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.33 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.14 |

| Tenure | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.29 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.29 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.52 | −0.00 | 0.00 | −0.43 |

| Social desirability | 0.11 | 0.03 | 4.04 *** | −0.09 | 0.03 | −3.35 ** | −0.07 | 0.03 | −2.64 ** | −0.05 | 0.03 | −1.94 |

| Perceived philanthropy awareness | 0.15 | 0.03 | 4.73 *** | −0.03 | 0.03 | −1.04 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.23 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.38 |

| Moral pride | −0.16 | 0.04 | −3.57 *** | −0.24 | 0.05 | −5.14 *** | ||||||

| Moral reputation maintenance concerns | 0.08 | 0.03 | 3.27 ** | |||||||||

| Moral pride × MRMCs | −0.12 | 0.04 | −3.32 *** | |||||||||

| R-SQUARE | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.12 | ||||||||

| ΔR2 | 0.03 | 0.07 | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ju, D.; Tang, Y.; Geng, S.; Lu, R.; Wang, W. The Organizational Halo: How Perceived Philanthropy Awareness Curbs Abusive Supervision via Moral Pride. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121706

Ju D, Tang Y, Geng S, Lu R, Wang W. The Organizational Halo: How Perceived Philanthropy Awareness Curbs Abusive Supervision via Moral Pride. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121706

Chicago/Turabian StyleJu, Dong, Yan Tang, Shu Geng, Ruobing Lu, and Weifeng Wang. 2025. "The Organizational Halo: How Perceived Philanthropy Awareness Curbs Abusive Supervision via Moral Pride" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121706

APA StyleJu, D., Tang, Y., Geng, S., Lu, R., & Wang, W. (2025). The Organizational Halo: How Perceived Philanthropy Awareness Curbs Abusive Supervision via Moral Pride. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1706. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121706