1. Introduction

Smartphones have become nearly ubiquitous among young adults, bringing convenience but also the risk of problematic smartphone use—often defined as an inability to control one’s mobile phone behavior despite negative consequences for daily functioning (

Wickord & Quaiser-Pohl, 2022). Researchers have used terms such as smartphone addiction, excessive smartphone use, mobile phone dependence, and nomophobia to describe this emerging behavioral pattern (

Mitchell & Hussain, 2018). Problematic smartphone use has been linked to a host of detrimental outcomes, including increased anxiety and depression, attention impairments, poorer academic performance, and sleep disturbances (

Li et al., 2024). For example, recent evidence among college populations indicates that students with more severe smartphone overuse report higher psychological distress and even reduced self-efficacy in their academic (

Li et al., 2024). These findings underscore why problematic smartphone use is now regarded as a significant public health and educational concern on campuses worldwide. Previous studies have identified adolescents as a particularly vulnerable group for smartphone overdependence (

Noh & Shim, 2024).

In the present study, digital competence is understood as a multidimensional construct that incorporates both technical–operational skills and self-regulatory–reflective abilities. Technical skills refer to the capacity to operate devices and applications efficiently, manage software, and perform functional digital tasks. In contrast, self-regulatory and reflective abilities involve evaluating the reliability of online information, managing privacy and safety settings, regulating one’s own digital behavior, and making intentional decisions about smartphone use. This distinction is essential for interpreting the study’s findings, as prior research suggests that reflective and self-regulatory components—rather than basic technical proficiency—are more strongly associated with healthier and less problematic technology engagement. Adolescents represent a particularly vulnerable group for smartphone overdependence, influenced by individual and contextual factors (

Noh & Shim, 2024).

Problematic smartphone use, as conceptualized in this study, refers to a pattern of maladaptive, excessive, and poorly regulated engagement with one’s smartphone that generates negative consequences in everyday functioning. To ensure conceptual clarity, the construct was operationalized using the Problematic Mobile Phone Use Questionnaire–Revised (PMPUQ-R), which identifies three objectively measurable dimensions: (a) dependent use, involving emotional or cognitive reliance on the device (e.g., anxiety or distress when the phone is unavailable); (b) prohibited use, referring to the use of smartphones in inappropriate or restricted contexts such as during class or while driving; and (c) dangerous use, which captures behaviors that pose safety risks, including texting while walking in traffic. This multidimensional framework provides a standardized and consistent definition of what is considered “problematic” within this research and allows for direct interpretation of the empirical findings.

In this manuscript, the term digital competence is used as the primary construct, following the definition proposed by the European Commission’s DigComp framework and the DCQ-US developers. Digital competence encompasses the knowledge, skills, and critical attitudes required to use digital technologies in a confident, responsible, and self-regulated manner. Although the terms digital competence and digital skills appear in the broader literature, they are not used interchangeably here. Digital competence is treated as a closely related umbrella concept emphasizing critical understanding, whereas digital skills are considered the technical and procedural abilities that form only one component of digital competence. Importantly, the construct measured in this study includes five domains: (1) information literacy (e.g., evaluating the credibility of online sources), (2) communication and collaboration (e.g., interacting appropriately in digital environments), (3) digital content creation (e.g., producing and editing digital materials), (4) safety and privacy (e.g., protecting personal data online), and (5) problem-solving (e.g., resolving technical issues or adapting to new digital tools). Together, these domains represent a multidimensional and behaviorally grounded definition of digital competence that can be meaningfully linked to patterns of smartphone use.

Conversely, in regions where digital infrastructure has expanded more recently, high rates of phone addiction are also being reported, as evidenced by studies in Egypt showing that nearly 59% of university students meet criteria for smartphone addiction (

Okasha et al., 2022), as well as multicountry surveys across Latin America documenting elevated levels of mobile phone overuse among medical students (

Izquierdo-Condoy et al., 2025).

Psychological defense has been conceptualized in psychology as a set of cognitive-emotional mechanisms that protect individuals from stress, dysregulation, and maladaptive behaviors (

Vaillant, 1992;

Cramer, 2006). Contemporary models further emphasize regulatory and coping processes that buffer individuals from problematic or addictive technology use (

Compas et al., 2017;

Elhai et al., 2022). In this context, digital competence may operate as a form of psychological defense, as it equips individuals with evaluative, self-regulatory, and critical-thinking skills that enable them to manage digital environments in a healthier manner. From this perspective, higher digital competence could function as a protective psychological mechanism that reduces vulnerability to compulsive checking, nomophobia-like anxiety, and risky phone-use behaviors.

Identifying protective factors that can mitigate problematic smartphone use is a current priority in scientific literature. Recent research converges on the idea that digital competence and digital competence functions as a psychological defenses against addictive behaviors related to mobile phone use. For example, studies conducted among university students and adolescents have shown that digital competence is associated with lower symptoms of addiction, higher levels of mental health, and greater self-regulation capacity (

Tso et al., 2022). Moreover, sleep quality and perceived social support act as mediating variables that explain how problematic mobile use affects students’ mental health, demonstrating that poorer sleep increases the risk of psychological distress (

Yang et al., 2023). Consequently, promoting digital competencies and self-regulation skills, as well as facilitating access to social support networks, is considered essential for reducing the prevalence of problematic mobile device use among young people and university students (

Tso et al., 2022).

Some empirical evidence supports the protective role of digital competence, for instance, a recent study of adolescents found that those with greater digital competence experienced fewer mental health problems indirectly by avoiding Internet addiction, indicating that digital skills can buffer against the harms of excessive online engagement (

Tao et al., 2023). Likewise, research on young adults in a university sports context reported that higher digital competence correlated with lower phubbing tendencies (snubbing others by looking at one’s phone) and better social well-being. These findings imply that improving individuals’ digital skills and awareness might promote healthier relationships with their devices. However, the literature is not entirely consistent. In one study of Egyptian undergraduates, higher self-reported digital media literacy was paradoxically associated with greater smartphone addiction.

The authors suggested that being more “tech savvy” might facilitate more frequent smartphone use (and thus higher addiction scores), especially if digital competence is defined largely by technical ability rather than critical self-regulation (

Okela, 2023). Similarly, recent evidence from diverse contexts, such as studies on Korean older adults and cross-cultural cohorts, underscores that stronger digital skills may not always protect from problematic smartphone use if the skills focus only on operational proficiency rather than critical and self-regulatory components (

Burgos et al., 2023). These mixed results highlight the importance of examining the digital competence–problematic smartphone use relationship in diverse cultural settings and clarifying which aspects of digital competence (technical proficiency vs. evaluative and self-regulatory skills) are most effective in curbing problematic use.

In this study, we distinguish between problematic smartphone use and problematic phone-related behaviors, two terms that may appear similar but refer to conceptually different levels of analysis. Problematic smartphone use refers to a multidimensional psychological construct assessed through standardized scales (e.g., the PMPUQ-R) that capture patterns such as dependence, loss of control, excessive use, and negative consequences. It represents an overall maladaptive pattern of interaction with the device. In contrast, problematic phone-related behaviors describe specific, observable actions—such as checking notifications reflexively, using the phone in prohibited contexts, extending usage beyond intended time, or experiencing discomfort when unable to check the device. These behaviors are individual components that can contribute to, but do not necessarily constitute, the broader construct of problematic smartphone use. For clarity and consistency, throughout the manuscript, we use problematic smartphone use to refer to the latent construct measured by the PMPUQ-R, and problematic behaviors when discussing specific behavioral indicators identified descriptively in the current sample.

To guide the empirical analysis, the following research questions were formulated:

RQ1. To what extent do Paraguayan university students report problematic smartphone use across the dimensions measured by the PMPUQ-R (dependent use, prohibited use, and dangerous use)?

RQ2. How do the different domains of digital competence (information literacy, communication, content creation, safety, and problem-solving) relate to problematic smartphone use?

RQ3. Does higher digital competence function as a protective factor against problematic smartphone use among Paraguayan university students?

In summary, the present study aims to investigate whether digital competence is associated with lower problematic smartphone use among university students in Paraguay. To our knowledge, this is the first Paraguayan study to explicitly probe this relationship, contributing Latin American data to a body of research previously dominated by Asian and Western samples. We hypothesized that students with higher digital competence would demonstrate significantly lower levels of problematic smartphone use—supporting the view of digital competence as a protective factor (

Pan et al., 2024). By testing this hypothesis, our goal is to inform prevention efforts; if a negative relationship is confirmed, it would suggest that fostering students’ digital competence, especially evaluative and self-regulatory skills, may be a valuable strategy to reduce smartphone-related problems and promote healthier behavioral patterns related to smartphone use in the university population (

Burgos et al., 2023).

Digital competence is a multidimensional construct that encompasses both technical–operational skills (e.g., navigating applications, adjusting device settings, managing files) and self-regulatory, evaluative, and critical skills (e.g., managing attention and notifications, evaluating online information credibility, protecting digital privacy, and making intentional decisions about smartphone use). This distinction is central to the present study because only the latter set of skills—reflective, critical, and regulatory—has been consistently associated with healthier digital behavior in previous research. By explicitly differentiating these two domains from the outset, the current work clarifies that the measurement approach employed (DCQ-US) captures not only operational proficiency but also the more psychologically protective competencies that help prevent maladaptive smartphone use.

4. Discussion

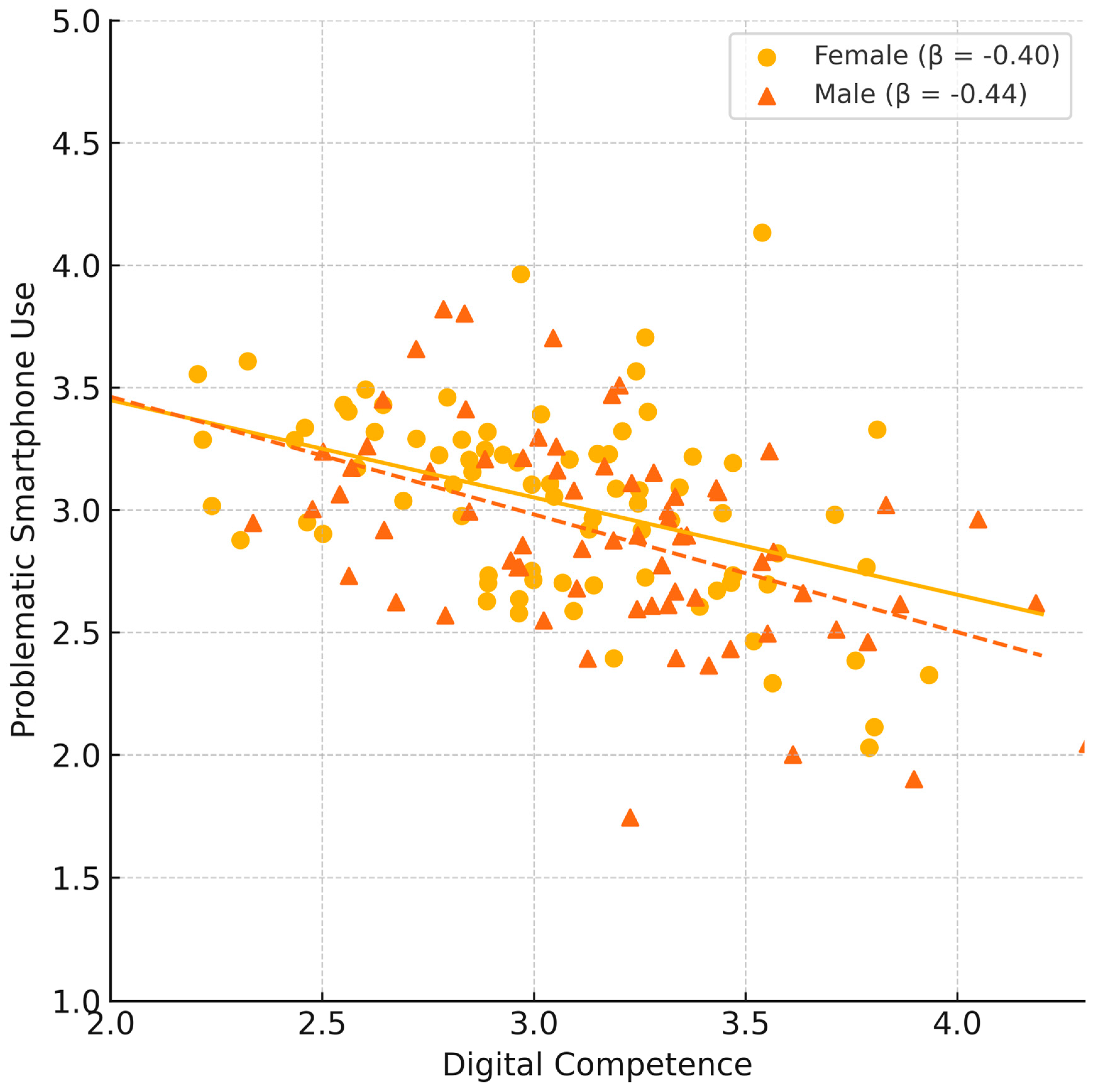

This study examined whether digital competence can act as a psychological buffer against problematic smartphone use among Paraguayan university students, and the findings provide clear evidence in support of this role. As predicted, students with higher digital competence scores tended to report significantly fewer problematic behaviors with their mobile phones. In practical terms, the most digitally skilled and savvy students were less “addicted” to their smartphones—they experienced fewer feelings of panic or anxiety when separated from their device, engaged less in inappropriate or risky phone use (such as using phones in class or while driving), and generally exerted better control over their smartphone habits. The magnitude of the effect (β ≈ −0.4) suggests that digital competence is an important factor, though certainly not the only factor, in unhealthy phone use tendencies (

Pan et al., 2024).

Although subscale-level analyses could not be performed with the anonymized dataset, the theoretical structure of the DCQ-US provides meaningful insight into how each dimension may differentially relate to problematic smartphone use. The critical and evaluative literacy dimension is expected to serve as the strongest protective factor, as students with higher evaluative skills are better able to identify manipulative digital design features, manage persuasive notifications, and regulate attention in digital environments. Safety and privacy management skills may also protect against maladaptive patterns by reducing anxiety and uncertainty related to notifications, personal data exposure, and digital risks. In contrast, technical-operational skills may have a weaker protective effect, as they reflect functional ability rather than self-regulatory competence. These theoretically grounded pathways align with recent research showing that reflective and self-regulatory aspects of digital competence—not merely operational skills—are the key factors associated with lower problematic smartphone use. This multidimensional interpretation reinforces our argument regarding the protective value of advanced, critical digital skills.

Our findings align with several theoretical perspectives and prior empirical studies; they echo results from a recent study on Turkish student-athletes, which found that higher digital competence was associated with lower phubbing behavior and better social well-being. In that context, athletes who were more competent with digital technology were less likely to compulsively check their phones and ignore real-life interactions, implying an ability to self-regulate and balance their phone use. Similarly, Tao et al. found that Hong Kong adolescents with greater digital competence were somewhat protected from the mental health harms of excessive screen time, partly by avoiding Internet addiction (

Tao et al., 2023). These convergent findings from different populations support the idea that digital competence fosters resilience against the adverse outcomes of high-tech engagement. The concept of digital competence as a protective factor can be seen through the lens of empowerment: students who know how to use technology effectively and who understand its pitfalls may consciously limit deleterious behaviors (like doom-scrolling at 3 a.m. or texting while driving), much as health-literate individuals might make better dietary or exercise choices.

It is also worth noting that our results reinforce the value of looking at positive psychosocial characteristics (here, digital skills) in addiction research, rather than focusing exclusively on deficits or risk traits. Much of the smartphone addiction literature has centered on what types of people are more prone to overuse—for example, those with high impulsivity, loneliness, or stress tend to have higher problematic smartphone use (

Mitchell & Hussain, 2018). While that approach is valuable, our study suggests an alternative and complementary approach: enhancing certain competencies might reduce everyone’s risk, regardless of their predispositions. In our sample, the negative link between digital competence and problematic use held true even after controlling for gender and age, which hints at a broadly applicable benefit. This finding aligns with general models of digital well-being, which propose that improving users’ skills and awareness can lead to more intentional and balanced technology use.

Despite the clear trend observed, it is important to interpret our results in light of some cultural and contextual factors. Paraguay is a country where the digital transformation in education has accelerated only in recent years. Compared to students in more tech-saturated environments (e.g., East Asia or Western Europe), Paraguayan university students might have more to gain from increases in digital competence, as there may be a wider gap between those with higher versus lower competence. In a context where digital education is still developing, students who attain a high level of digital competence may also internalize more knowledge about the consequences of overuse and strategies for prevention. For example, being aware of apps that track screen time, or knowing how constant notifications can hijack attention. This awareness can translate into behaviors like turning off non-essential notifications, setting usage limits, or engaging in “digital detox” periods, which would naturally reduce problematic usage.

Another point of discussion is the nuanced nature of digital competence itself. Digital competence is a multifaceted construct, and not all components may guard equally against problematic use. Our measure encompassed technical skills (like installing software or troubleshooting devices) as well as higher-order skills (like evaluating information and understanding online privacy). It is conceivable that the critical and reflective dimensions of digital competence are doing the “heavy lifting” in reducing smartphone addiction, rather than the pure technical know-how. In other words, a student who is merely very tech-savvy (able to use many apps, etc.) but lacks critical self-regulation might actually engage more with their phone, potentially increasing risk—this scenario might describe the Egyptian finding where “digital media literacy” correlated positively with addiction scores. That study (

Tao et al., 2023) measured digital competence in terms of media usage and technical knowledge, which could naturally correlate with more frequent phone use and thus more opportunities for addiction. By contrast, if digital competence is measured with an emphasis on reflective use and understanding consequences (as the DCQ-US does to some extent), higher scores should correlate with more prudent behavior, which is what we observed. Future research could delve deeper into which specific competencies (e.g., cybersecurity knowledge, content creation skills, information evaluation, or even digital well-being awareness) are most protective against problematic smartphone use. This would help tailor educational interventions to focus on the most impactful skill areas.

Our study also contributes region-specific insight by focusing on Latin American university students. The Latin American context presents both similarities and differences compared to other regions regarding smartphone use. Similar to reports from Asia and Europe, we found a high prevalence of phone-related anxiety (nomophobia) in Paraguayan students (nearly three-quarters felt anxious without their phones), underlining that youth from developing digital economies are just as attached to their devices as those elsewhere. On the other hand, the strong connection we observed between digital competence and reduced problematic smartphone use might reflect particular educational or cultural dynamics in Paraguay. It is possible that universities in our sample that emphasize technology training also inadvertently teach digital responsibility, or that students who seek digital skill development are more academically engaged and thus less likely to succumb to digital distractions. Recent transnational studies conducted across Latin America highlight significant variations in levels of digital competence and the necessity for developing specific plans for digital skills at the university level. Furthermore, preliminary evidence from neighboring countries is encouraging: a recent multicenter study across six Latin American nations recommended enhancing digital competence as part of strategies to address smartphone overuse and its health impacts on students (

Izquierdo-Condoy et al., 2025). Our data provide empirical support for those recommendations, showing the direct association between digital competence and healthier usage patterns.

Our findings support the interpretation of digital competence as a psychological defense mechanism. Classical psychological theories describe defense processes as strategies that reduce exposure to emotional distress and impulsive behaviors (

Vaillant, 1992;

Cramer, 2006). Students with higher digital competence showed fewer anxiety-related behaviors (e.g., discomfort when unable to check their smartphone) and fewer maladaptive habits such as compulsive checking or extended unplanned use. This pattern aligns with contemporary views of coping and self-regulation in digital contexts, suggesting that digital competence may buffer individuals from the emotional and behavioral dysregulation associated with problematic smartphone use (

Compas et al., 2017;

Elhai et al., 2022).

RQ1 asked to what extent Paraguayan university students report problematic smartphone use.

Our findings show moderate to high levels of problematic smartphone use across the three PMPUQ-R dimensions (dependent, prohibited, and dangerous use), with a high prevalence of phone-related anxiety (72%), indicating that problematic smartphone behaviors are widespread in this population.

RQ2 examined the relationship between the different domains of digital competence and problematic smartphone use.

The results indicate a clear negative association between overall digital competence and problematic smartphone use. Students with higher digital competence scores tended to report fewer maladaptive phone behaviors, suggesting that digital competence is inversely related to problematic use patterns.

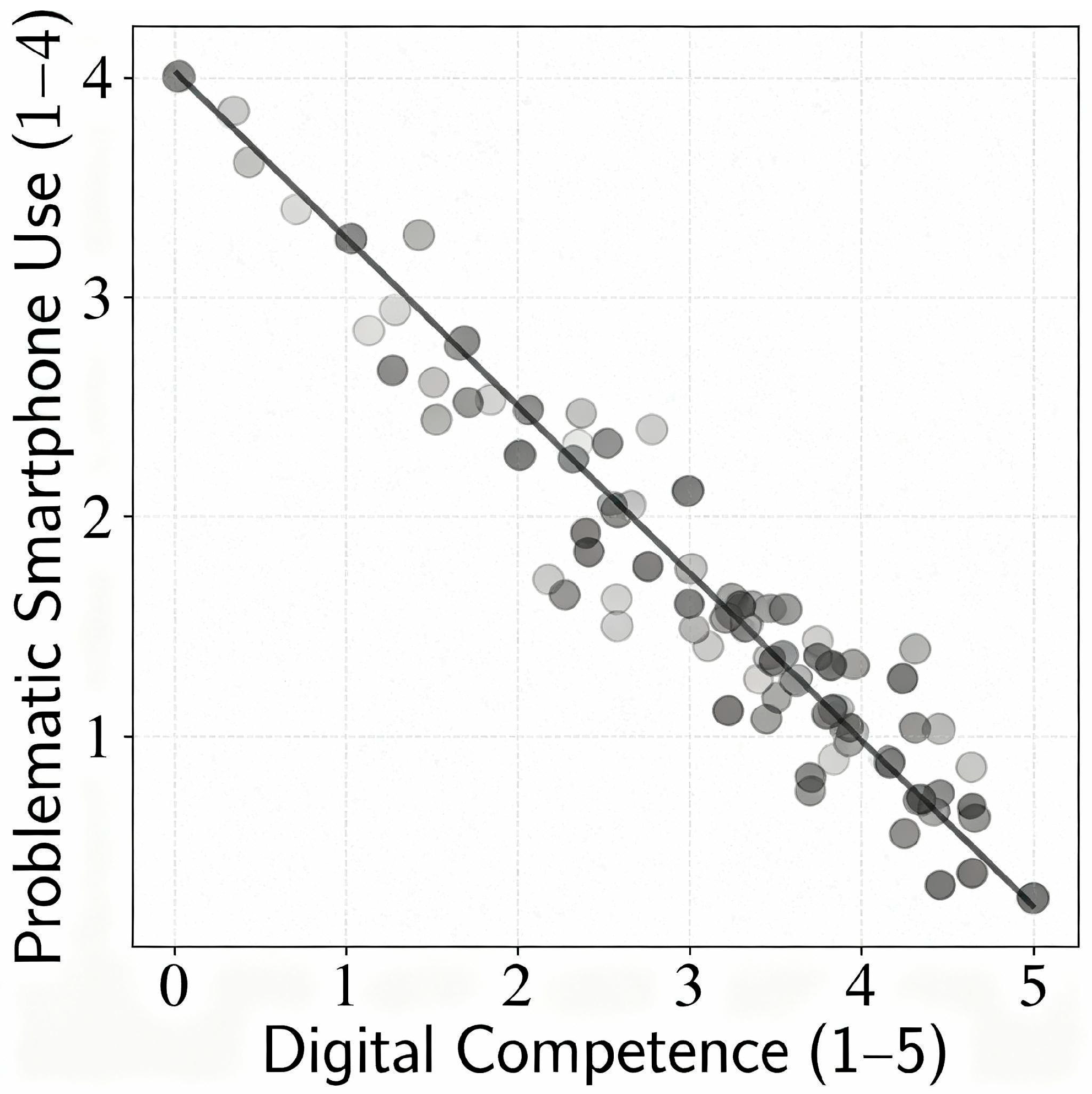

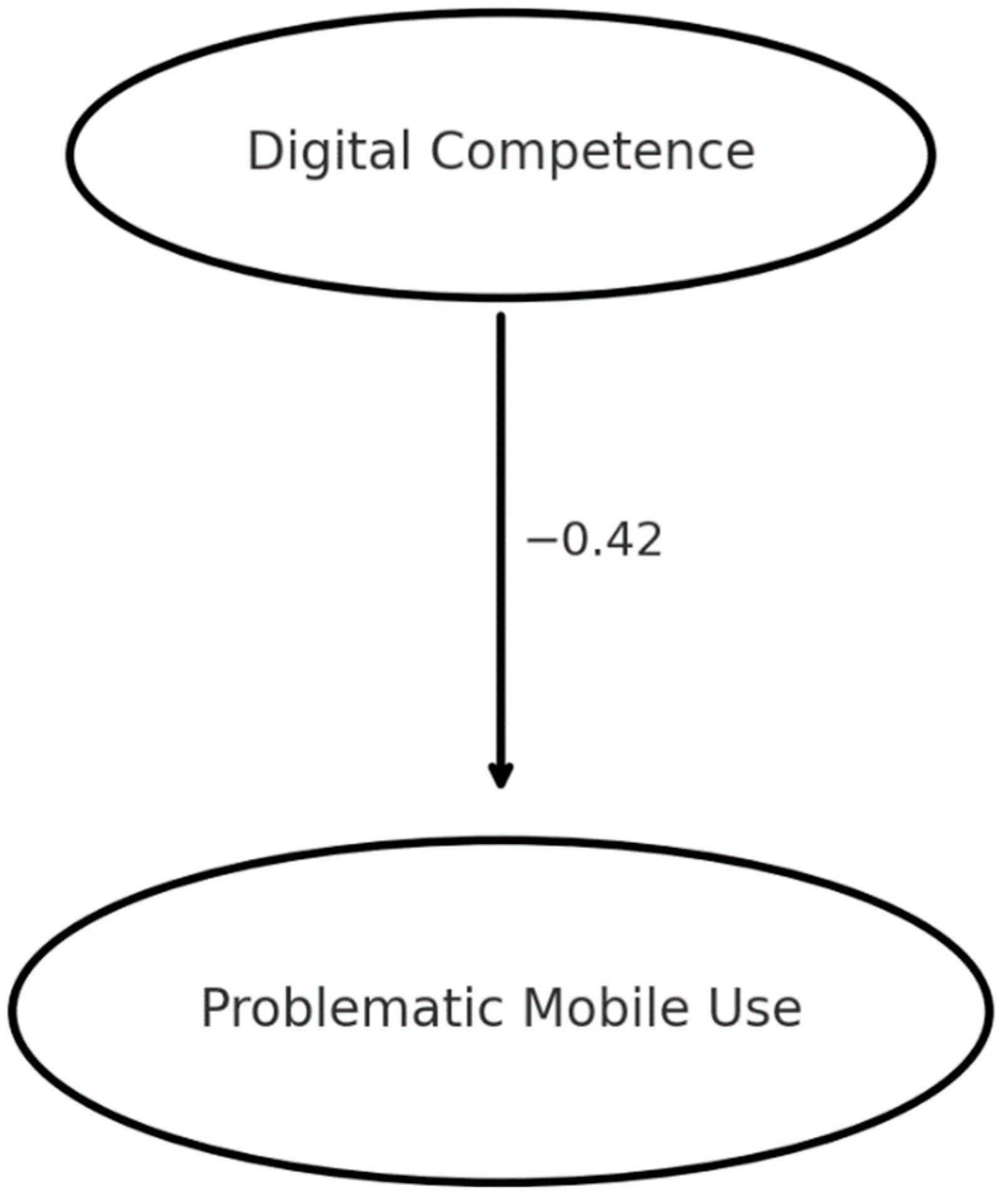

RQ3 investigated whether digital competence functions as a protective factor against problematic smartphone use.

The structural equation model confirmed that digital competence significantly and negatively predicts problematic smartphone use (β = −0.42, p < 0.001), supporting its role as a psychological protective factor among Paraguayan university students. Taken together, these findings provide a clear and coherent answer to the three research questions proposed in this study.

4.1. Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of this research. First, the study’s cross-sectional design restricts our ability to infer causality. While our theoretical model posits that higher digital competence leads to lower problematic use, it is also plausible that students who reduce their phone addiction have more time and mental bandwidth to develop digital skills—or that an unmeasured third variable, such as general self-regulation or socio-economic status, influences both domains (

Al-Abyadh et al., 2024). Longitudinal and intervention studies using rigorous designs (

Lu et al., 2025) would be valuable to clarify the temporal ordering and underlying mechanisms. Second, all measures were self-reported, which introduces the potential for common-method bias and social desirability effects. Past research shows students may overestimate their digital abilities or underestimate their problematic use due to self-perception (

Parry et al., 2021). Including objective indicators in future studies—such as logged smartphone use data or standardized digital skill tests—would strengthen the validity of our findings.

Third, our sample, while sizeable, was not randomly selected and consisted predominantly of urban, tech-accessible university students. This raises the issue of generalizability, as our results may not extend to rural students, older adults, or broader Paraguayan populations. Self-selection bias may have occurred, with tech-savvy participants being more likely to respond (

Al-Abyadh et al., 2024). Although efforts were made to mitigate bias through broad recruitment and anonymity assurances, the limitation remains. Finally, cultural factors specific to Paraguay (e.g., collectivist values, academic norms, smartphone use culture) were not explicitly measured but could influence the observed relationships (

Brand et al., 2019). Qualitative research could enrich our findings by exploring how students interpret “healthy” versus “unhealthy” phone use in their own context.

A further limitation concerns the absence of potentially relevant sociodemographic and academic covariates that could influence the association between digital competence and problematic smartphone use. Variables such as socioeconomic status, academic performance, access to digital resources, and prior digital training were not included in the present analyses. These factors may partially account for individual differences in both digital skill development and smartphone-related behaviors. Future studies would benefit from incorporating these covariates into multivariate models to better isolate the unique contribution of digital competence and to reduce the risk of residual confounding in the observed relationships.

4.2. Future Directions

Building on these findings, future research should employ intervention studies—such as implementing a digital competence workshop or curriculum and then tracking smartphone usage outcomes over time (

Lu et al., 2025). If digital competence training demonstrably reduces problematic smartphone use, this would strongly justify universities and policymakers investing in such programs. Additionally, investigations should examine potential mediators (such as self-regulation, time management, or technology mindfulness) and explore how physical activity may interact with digital behaviors (

Wang et al., 2024). Another worthwhile direction is to determine whether the protective effect of digital competence extends to other digital addictions—such as problematic social media use, online gaming, or more general internet addiction. Given the frequent co-occurrence of these behaviors, strengthening digital competence may offer broad benefits across multiple domains of digital life, a hypothesis that warrants verification (

Brand et al., 2019).

To provide a deeper behavioral interpretation, we expanded the Results section by linking the statistical findings to concrete item-level behaviors assessed in the survey. The observed patterns suggest that anxiety-related behaviors (e.g., discomfort when unable to check the phone) coexist with habitual use patterns such as checking notifications reflexively or multitasking with social media during study periods.

Beyond the global negative association between digital competence and problematic smartphone use, our results align with specific behavioral manifestations captured in the survey. The descriptive analyses revealed clear patterns connecting students’ daily phone habits with their total PMPUQ-R scores. Behaviors such as immediately checking notifications upon receipt, extending phone use beyond intended time, or multitasking with social media during study periods were consistently associated with higher problematic use scores. These concrete behaviors provide an applied behavioral context to the quantitative findings, illustrating the mechanisms through which inadequate digital competence may contribute to maladaptive phone-related routines.

In addition, individual items of the DCQ-US shed light on why students with higher digital competence show fewer problematic behaviors. Higher-competence students reported greater ability to evaluate the credibility of online information, adjust privacy and notification settings, solve digital problems, and use digital tools in a planned and intentional manner. These skills likely enhance self-regulation, reduce impulsive device checking, and mitigate anxiety-driven behaviors (e.g., discomfort when unable to access the phone). As such, the survey items themselves help explain the psychological processes underlying the observed associations.

Taken together, the alignment between item-level behaviors (e.g., compulsive checking, extended usage, nomophobia-like discomfort) and broader PMPUQ-R dimensions (dependent use, prohibited use, and dangerous use) reinforces the behavioral validity of the constructs measured. This expanded interpretation strengthens the theoretical relevance and practical significance of the findings for behavioral science research.

Integrating digital competence training into university curricula can be concretely operationalized across disciplines through domain-specific applications. In education programs, students can be trained to critically evaluate online information sources, design safe and responsible digital learning environments, and model healthy smartphone habits for school-aged learners. In health sciences, digital competence can support the responsible use of mobile health applications, data privacy management, and the prevention of technology-related anxiety or dependence among patients. In engineering and computer science, students can engage in secure configuration of devices, ethical management of digital systems, and the design of user-focused technologies that minimize addictive patterns. In social sciences and psychology, curricular modules can focus on analyzing digital behaviors, interpreting smartphone-related data, and understanding the cognitive and emotional mechanisms underlying problematic use. These concrete curricular entry points demonstrate how digital competence can be meaningfully embedded across faculties, supporting the development of healthier and more intentional technology engagement among university students.

Future research should also examine whether the protective mechanisms of digital competence extend to other forms of digital dependence, such as problematic social media use, compulsive gaming, streaming overuse, or short-form video addiction. Theoretical frameworks such as the I-PACE model (

Brand et al., 2019), which situates digital addiction within the interaction of personal predispositions, affective regulation, and executive control, offer a useful foundation for generating specific hypotheses. For example, it may be hypothesized that: (H1) higher digital competence predicts lower problematic social media use through improved self-regulation; (H2) evaluative and reflective digital skills mitigate compulsive gaming by enhancing awareness of persuasive design elements; and (H3) digital safety and privacy management skills reduce excessive engagement with short-form video platforms by limiting algorithm-driven exposure. Testing these hypotheses across different digital behaviors would clarify whether digital competence acts as a broad protective factor or whether its effects vary across specific digital environments.