Breaking the Silence: Willingness to Intervene in Cases of Intimate Partner Violence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Questionnaire Development and Measures

- ▪

- Affirmative intervention: This dimension refers to the expectation that people close to the victim, or even bystanders, should intervene in cases of IPV. Initially, it was measured by six items: “A neighbor should intervene if he or she witnesses domestic violence,” “A friend should intervene if he or she witnesses domestic violence,” “I would intervene if I witnessed domestic violence,” “A family member should intervene if he or she witnesses domestic violence,” “A passerby should intervene if he or she witnesses domestic violence,” and “A neighbor/friend should intervene if he or she sees signs of child abuse.” In our study, only the first five items loaded substantially on a single factor and were therefore retained for the analysis (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

- ▪

- Police intervention: This type of intervention underscores the necessity of law enforcement involvement in IPV situations. It was measured by four items (Cronbach’s α = 0.88): “An individual should contact the police if they are threatened with a weapon,” “An individual should contact the police after his or her partner is physically abusive,” “An individual should contact the police if abuse occurs when a child is present,” and “An individual should contact the police if their partner threatens abuse.”

- ▪

- No Intervention: This dimension captures the belief that IPV is a private matter and that outside parties should only intervene in extreme circumstances or with clear evidence. The initial scale comprised seven items, with one example being “An individual shouldn’t contact the police unless they have proof of a domestic assault.” Following factor validation, only two items were retained for analysis due to poor loadings of others (Cronbach’s α = 0.98): “Verbal arguments with threats of physical harm by the man to his partner should not be reported to the police,” and “Verbal arguments with threats of physical harm by the woman to her partner should not be reported to the police.” Modifications were made to these statements to clarify their reference to IPV (the words in italic text were added).

- ▪

- Intervention threshold: his aspect was measured initially with three items: “An individual should contact the police if their partner threatens abuse,” “A man should be automatically arrested for any signs of abuse on a woman,” and “A woman should be automatically arrested for any signs of abuse on a man.” However, only the latter two items exhibited significant loadings on a unified factor. Since this content did not reflect a willingness to intervene but relatively strong views regarding formal consequences of IPV, we excluded this scale from our analysis.

- ▪

- Attitudes towards physical violence: Based on research by Davidson and Canivez (2012), this included statements like, “It is all right for a partner to hit the other if they are unfaithful,” “It is all right for a partner to slap the other if insulted or ridiculed,” “It is all right for a partner to slap the other’s face if challenged,” and “It is all right for a partner to hit the other if they flirt with others” (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

- ▪

- Attitudes towards psychological IPV: Developed from the WHO questionnaire on IPV, this dimension included statements such as, “It is acceptable for a partner to constantly insult the other privately,” “constantly humiliate the other in front of others,” “threaten to hurt the other partner,” and “constantly belittle the other partner” (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

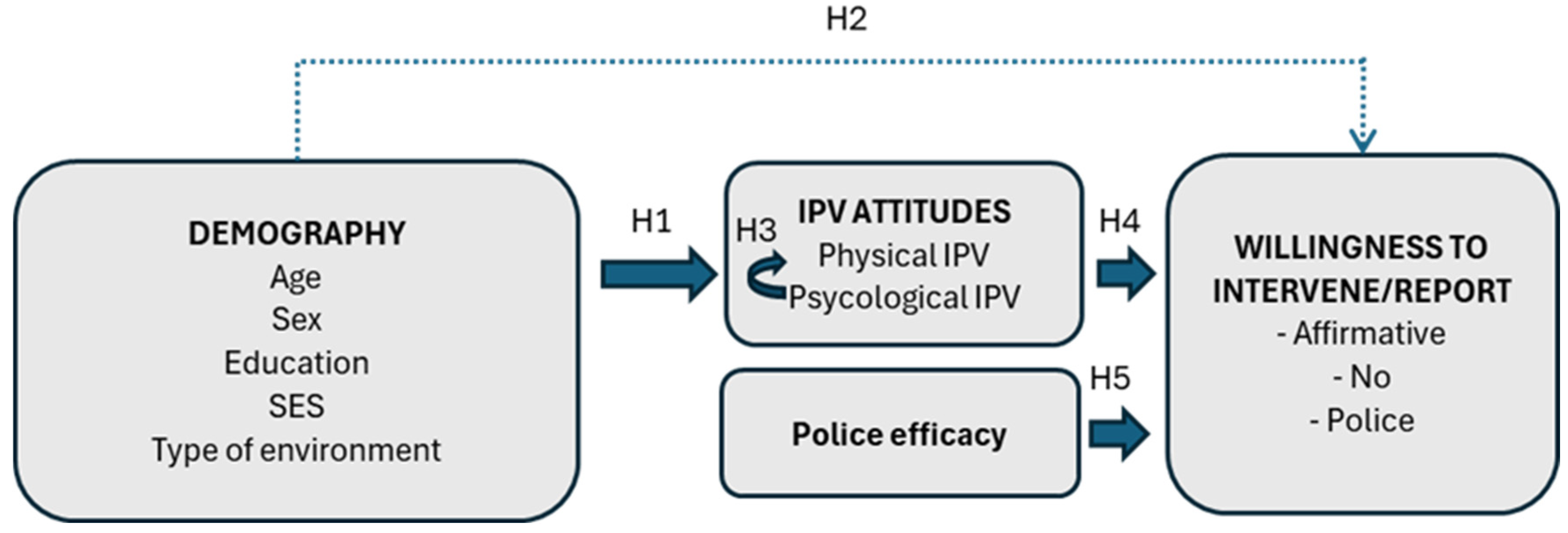

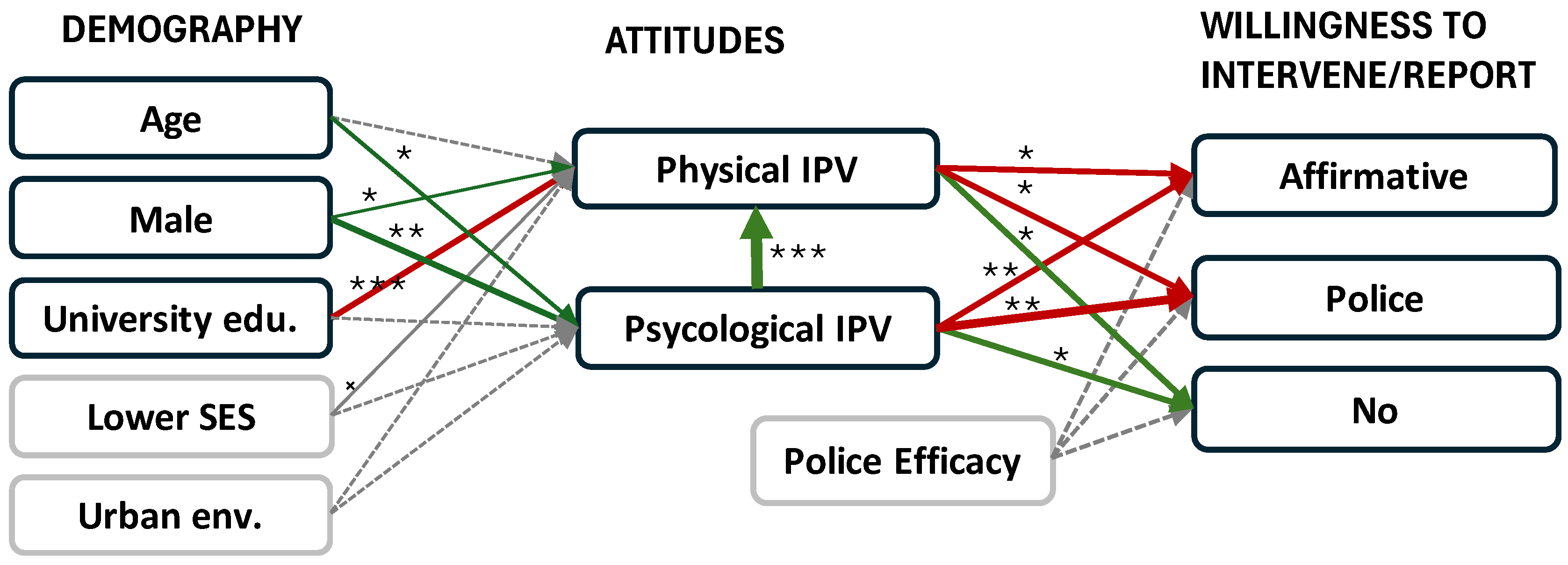

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IPV | Intimate partner violence |

| SES | Socio-economic status |

| RMSEA | Root mean square error of approximation |

| CFI | Comparative fit index |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| FRA | European Union Agency for Human Rights |

| NFI | Normed Fit Index |

| NNFI | Tucker–Lewis index |

| IFI | Incremental Fit Index |

References

- Alfredsson, H., Ask, K., & von Borgstede, C. (2014). Motivational and cognitive predictors of the propensity to intervene against intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 1877–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusen, J., McDonald, M., & Emery, B. (2023). Intimate partner violence: A clinical update. Nurse Practitioner, 48, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, F. A., & Ali, R. A. (2021). Jordanian men’s and women’s attitudes toward intimate partner violence and its correlates with family functioning and demographics. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, NP2883–NP2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenes-Sastre, M., Spencer, C. M., Alonso-Ferres, M., Lorente, M., & Expósito, F. (2024). How severity of intimate partner violence is perceived and related to attitudinal variables? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 76, 101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H., & Homburg, C. (1996). Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, A. G., Herzing, J. M. E., Cornesse, C., Sakshaug, J. W., Krieger, U., & Bossert, D. (2017). Does the recruitment of offline households increase the sample representativeness of probability-based online panels? Evidence from the German internet panel. Social Science Computer Review, 35, 498–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, A., & Hoogland, J. J. (2001). The robustness of LISREL modeling revisited. In R. Cudeck, S. du Toit, & D. Sörbom (Eds.), Structural equation models: Present and future. A festschrift in honor of Karl Jöreskog (pp. 139–168). Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Cinquegrana, V., Baldry, A. C., & Pagliaro, S. (2017). Intimate partner violence and bystanders’ helping behaviour: An experimental study. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 10, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, J. E., Giordano, P. C., Longmore, M. A., & Manning, W. D. (2019). The development of attitudes toward intimate partner violence: An examination of key correlates among a sample of young adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34, 1357–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M. M., & Canivez, G. L. (2012). Attitudes toward violence scale: Psychometric properties with a high school sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 3660–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermer, A. E., Roach, A. L., Coleman, M., & Ganong, L. (2021). Deconstructing attitudes about intimate partner violence and bystander intervention: The roles of perpetrator gender and severity of aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, NP896–NP919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Institute for Gender Equality. (2025). Gender equality index 2024: Slovenia. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-equality-index/2024/country/SI (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Filipčič, K., Drobnjak, M., Plesničar, M. M., & Bertok, E. (2021). Intimate partner violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Revija za Kriminalistiko in Kriminologijo, 72, 65–78. Available online: https://www.policija.si/images/stories/Publikacije/RKK/PDF/2021/01/RKK2021-01_KatjaFilipcic_IntimnopartnerskoNasiljeVCasuCovid-19.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FRA. (2014). Violence against women: An EU-wide survey main results violence against women: An eu-wide survey. FRA. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, E., García, F., & Lila, M. (2009). Public responses to intimate partner violence against women: The influence of perceived severity and personal responsibility. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 12, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, E., & Herrero, J. (2006). Public attitudes toward reporting partner violence against women and reporting behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, E., Lila, M., & Santirso, F. A. (2020). Attitudes toward intimate partner violence against women in the European union: A systematic review. European Psychologist, 25, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, E., Martín-Fernández, M., Marco, M., Santirso, F. A., Vargas, V., & Lila, M. (2018). The willingness to intervene in cases of intimate partner violence against women (WI-IPVAW) Scale: Development and validation of the long and short versions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice Hall International. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarros-Basterretxea, J., Fernández-Álvarez, N., Torres-Vallejos, J., & Herrero, J. (2024). Perceived reportability of intimate partner violence against women to the police and help-seeking: A national survey. Psychosocial Intervention, 33, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C., Mercer, A., Keeter, S., Hatley, N., Mcgeeney, K., & Gimenez, A. (2016). Evaluating online nonprobability surveys. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Khawaja, M., Linos, N., & El-Roueiheb, Z. (2008). Attitudes of men and women towards wife beating: Findings from Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C., & Ferraresso, R. (2022). Factors associated with willingness to report intimate partner violence (IPV) to police in South Korea. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37, NP10862–NP10882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knežević Hočevar, D. (2016). Nasilje v Družinah v Okoljih, Kjer »vsak Vsakega Pozna”. Nekateri Premisleki. [“Domestic Violence in Environments Where ‘Everyone Knows Everyone’: Some Reflections.]. Socialno Delo, 55, 39–54. Available online: https://www.revija-socialnodelo.si/mma/Nasilje_URN_NBN_SI_DOC-OAHUOEX1.pdf/2019011610521799/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Leemis, R. W., Friar, N., Khatiwada, S., Chen, M. S., Kresnow, M., Smith, S. G., Caslin, S., & Basile, K. C. (2022). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: 2016/2017 report on intimate partner violence. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, C. M., Aizpurua, E., & Rollero, C. (2021). None of my business? An experiment analyzing willingness to formally report incidents of intimate partner violence against women. Violence Against Women, 28, 2163–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medarić, Z. (2011). Domestic violence against women in Slovenia: A public problem? Revija za Socijalnu Politiku, 1, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, A. W., Kreuter, F., Keeter, S., & Stuart, E. A. (2017). Theory and practice in nonprobability surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 81, 250–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacilli, M. G., Pagliaro, S., Loughnan, S., Gramazio, S., Spaccatini, F., & Baldry, A. C. (2016). Sexualization reduces helping intentions towards female victims of intimate partner violence through mediation of moral patiency. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, S., Pacilli, M. G., & Baldry, A. C. (2020). Bystanders’ reactions to intimate partner violence: An experimental approach. European Review of Social Psychology, 31, 149–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, P., Prakash, J., Patra, B., & Khanna, P. (2018). Intimate partner violence: Wounds are deeper. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 60, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, M., & Knowles, A. (2001). Domestic violence: Attributions, recommended punishments and reporting behaviour related to provocation by the victim. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 8, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado Rivera, M. A., Ortiz Hernandez, Y. A., Motta Tautiva, P. A., Quevedo, O. G., & Guillén Puerto, A. J. (2024). Intimate partner violence attitudes: Who tolerates the most? International Journal of Psychological Research, 17, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prislan, K., Svetič, R., Mihelič, A., & Lobnikar, B. (2022). Quality and adequacy of responding to domestic violence in Slovenia: The victims’ perspective. Revija za Kriminalistiko in Kriminologijo, 73, 107–123. Available online: https://www.policija.si/images/stories/Publications/JCIC/PDF/2022/02/JCIC2022-02_KajaPrislan_QualityAndAdequacyOfRespondingToDomesticViolence.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Reyal, H. P., Perera, K. M. N., & Guruge, G. N. D. (2020). Knowledge and Attitude Towards Intimate Partner Violence Among Ever-Married Women: A Cross-Sectional Study from Sri Lanka. Advanced Journal of Social Science, 7(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satorra, A. (2000). Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In R. D. H. Heijmans, D. S. G. Pollock, & A. Satorra (Eds.), Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis (Vol. 36, pp. 233–247). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4615-4603-0. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Montilla, C., Valor-Segura, I., Padilla, J. L., & Lozano, L. M. (2020). Public helping reactions to intimate partner violence against women in European countries: The role of gender-related individual and macrosocial factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivarajasingam, V., Webber, I., Riboli-Sasco, E., Alaa, A., & El-Osta, A. (2022). Investigating public awareness, prevailing attitudes and perceptions towards domestic violence and abuse in the United Kingdom: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 22, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. (2020). Women more frequently victims of intimate partner as well as non-partner violence. Available online: https://www.stat.si/StatWeb/en/News/Index/10159 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Steenkamp, J. B. E. M., & van Trijp, H. C. M. (1991). The use of LISREL in validating marketing constructs. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 8, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stith, S. M., Smith, D. B., Penn, C. E., Ward, D. B., & Tritt, D. (2004). Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylaska, K. M., & Edwards, K. M. (2014). Disclosure of intimate partner violence to informal social support network members. Trauma Violence Abuse, 15, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C. A., & Sorenson, S. B. (2005). Community-based norms about intimate partner violence: Putting attributions of fault and responsibility into context. Sex Roles, 53, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E., Banyard, V., Grych, J., & Hamby, S. (2016). Not all behind closed doors: Examining bystander involvement in intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34, 3915–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T. D., Nguyen, H., & Fisher, J. (2016). Attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women among women and men in 39 low- and middle-income countries. PLoS ONE, 11, e0167438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN WOMEN. (2020). COVID-19 and ending violence against women and girls. UN Women. [Google Scholar]

- Ursachi, G., Horodnic, I. A., & Zait, A. (2015). How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Economics and Finance, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valicon. (2024). JazVem. Available online: https://www.jazvem.si/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Vázquez, D., Aizpurua, E., Copp, J., & Ricarte, J. J. (2021). Perceptions of violence against women in Europe: Assessing individual- and country-level factors. European Journal of Criminology, 18, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2021). Violence against women, 2018 estimates. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2024). Violence against women. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Willis-Esqueda, C., & Delgado, R. H. (2020). Attitudes toward violence and gender as predictors of interpersonal violence interventions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35, 809–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, T. H., & Mulla, M. M. (2012). Social norms for intimate partner violence in situations involving victim infidelity. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 3389–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worden, A. P., & Carlson, B. E. (2005). Attitudes and beliefs about domestic violence: Results of a public opinion survey. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 1219–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeager, D. S., Krosnick, J. A., Chang, L., Javitz, H. S., Levendusky, M. S., Simpser, A., & Wang, R. (2011). Comparing the accuracy of RDD telephone surveys and internet surveys conducted with probability and non-probability samples. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75, 709–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youstin, T. J., & Siddique, J. A. (2019). Psychological Distress, Formal Help-Seeking Behavior, and the Role of Victim Services Among Violent Crime Victims. Victims & Offenders, 14(1), 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Std. Loading | |

|---|---|

| Attitudes towards psychological violence (CR = 0.94; AVE = 0.80) | |

| It is all right for the partner to… | |

| constantly insult the other privately | 0.85 |

| constantly humiliate the other in front of others | 0.93 |

| threaten to hurt the other partner | 0.91 |

| constantly belittle the other partner. | 0.88 |

| Attitudes towards physical violence (CR = 0.91; AVE = 0.73) | |

| It is all right for the partner to… | |

| hit the other if they are unfaithful. | 0.82 |

| slap the other if insulted or ridiculed. | 0.90 |

| slap the other’s face if challenged. | 0.88 |

| hit the other if they flirt with others. | 0.81 |

| Affirmative intervention (CR = 0.91; AVE = 0.68) | |

| A neighbor should intervene if he or she witnesses domestic violence. | 0.8 |

| A friend should intervene if he or she witnesses domestic violence. | 0.7 |

| I would intervene if I witnessed domestic violence. | 0.78 |

| A family member should intervene if he or she witnesses domestic violence. | 0.91 |

| A passerby should intervene if he or she witnesses domestic violence. | 0.91 |

| Police intervention (CR = 0.89; AVE = 0.68) | |

| An individual should contact the police if he or she is threatened with a weapon. | 0.79 |

| An individual should contact the police after his or her partner is physically abusive. | 0.92 |

| An individual should contact the police if abuse occurs when a child is present. | 0.85 |

| An individual should contact the police if his or her partner threatens abuse. | 0.72 |

| No Intervention (CR = 0.92; AVE = 0.85) | |

| Verbal arguments with threats of physical harm by the man to his intimate partner should not be reported to the police. | 0.9 |

| Verbal arguments with threats of physical harm by the woman to her intimate partner should not be reported to the police. | 0.94 |

| Police effectiveness (CR = 0.83; AVE = 0.55) | |

| Police intervention in cases of domestic violence is swift (officers arrive at the scene quickly). | 0.69 |

| Police intervention in cases of domestic violence is effective (the violence is successfully stopped). | 0.88 |

| The police can successfully intervene in cases of domestic violence. | 0.63 |

| Police interventions successfully stop domestic violence. | 0.75 |

| n | Min | Max | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes towards physical violence | 600 | 1 | 5 | 1.64 | 0.73 |

| Attitudes towards psychological violence | 600 | 1 | 5 | 1.41 | 0.6 |

| Affirmative intervention | 600 | 1 | 5 | 4.26 | 0.64 |

| Police intervention | 600 | 1 | 5 | 4.6 | 0.53 |

| No intervention | 600 | 1 | 5 | 1.97 | 0.87 |

| Police Efficacy | 600 | 1 | 5 | 2.88 | 0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hober, N.; Erčulj, V.I. Breaking the Silence: Willingness to Intervene in Cases of Intimate Partner Violence. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1680. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121680

Hober N, Erčulj VI. Breaking the Silence: Willingness to Intervene in Cases of Intimate Partner Violence. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1680. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121680

Chicago/Turabian StyleHober, Nika, and Vanja Ida Erčulj. 2025. "Breaking the Silence: Willingness to Intervene in Cases of Intimate Partner Violence" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1680. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121680

APA StyleHober, N., & Erčulj, V. I. (2025). Breaking the Silence: Willingness to Intervene in Cases of Intimate Partner Violence. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1680. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121680