The Relationship Between Economic Pressure, Emotional Neglect and Anxiety Among Chinese Left-Behind Children: Based on Response Surface Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Hypothesis 1: Under congruence, anxiety among left-behind children increases progressively with rising economic pressure and emotional neglect.

- Hypothesis 2: Under incongruence, the effects of “high economic pressure—low emotional neglect” and “low economic pressure—high emotional neglect” on left-behind children’s anxiety differ.

- Hypothesis 3: Perceived discrimination will mediate the relationships between economic pressure, emotional neglect, and anxiety among left-behind children.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Ethics Procedures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Measurement Questionnaire

2.4.1. Economic Pressure

2.4.2. Emotional Neglect

2.4.3. Perception of Discrimination

2.4.4. Anxiety

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Result

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. The Correlation Between Economic Stress, Emotional Neglect, Perception of Discrimination and Anxiety

3.3. Polynomial Regression and Response Surface Analysis

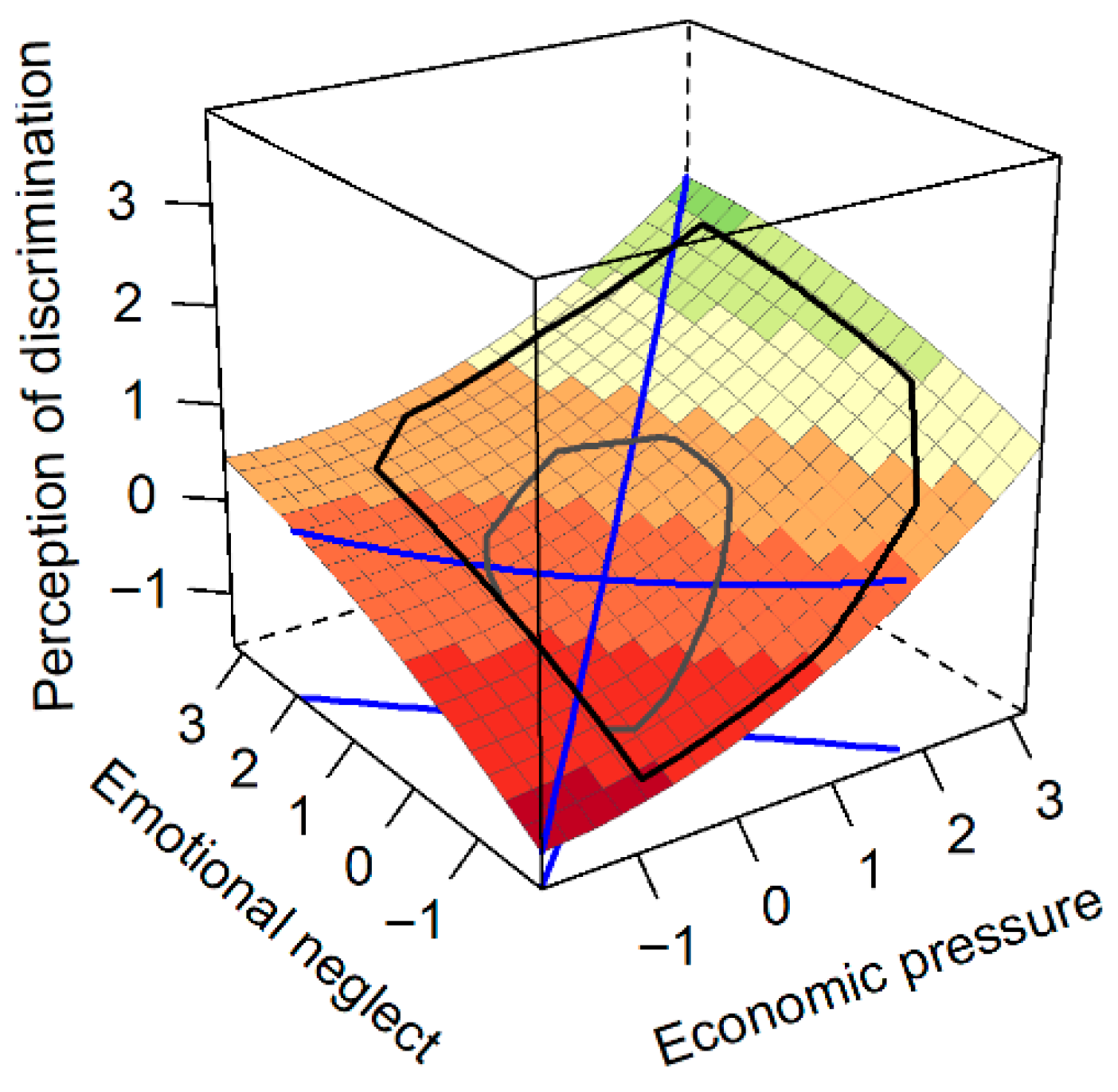

3.4. Response Surface Analysis of Economic Pressure, Emotional Neglect, and Perceived Discrimination

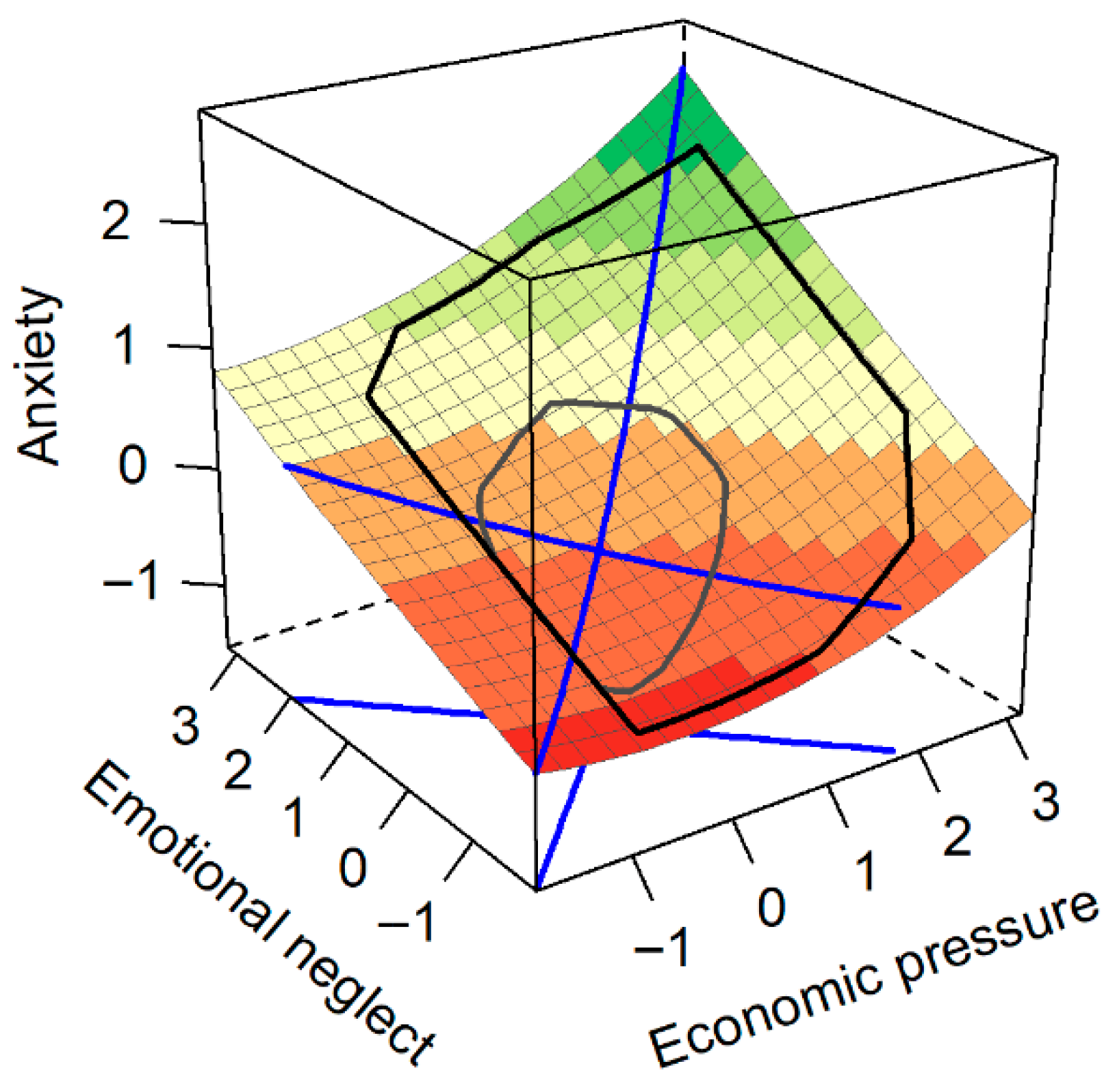

3.5. Response Surface Analysis of Economic Pressure, Emotional Neglect, and Anxiety

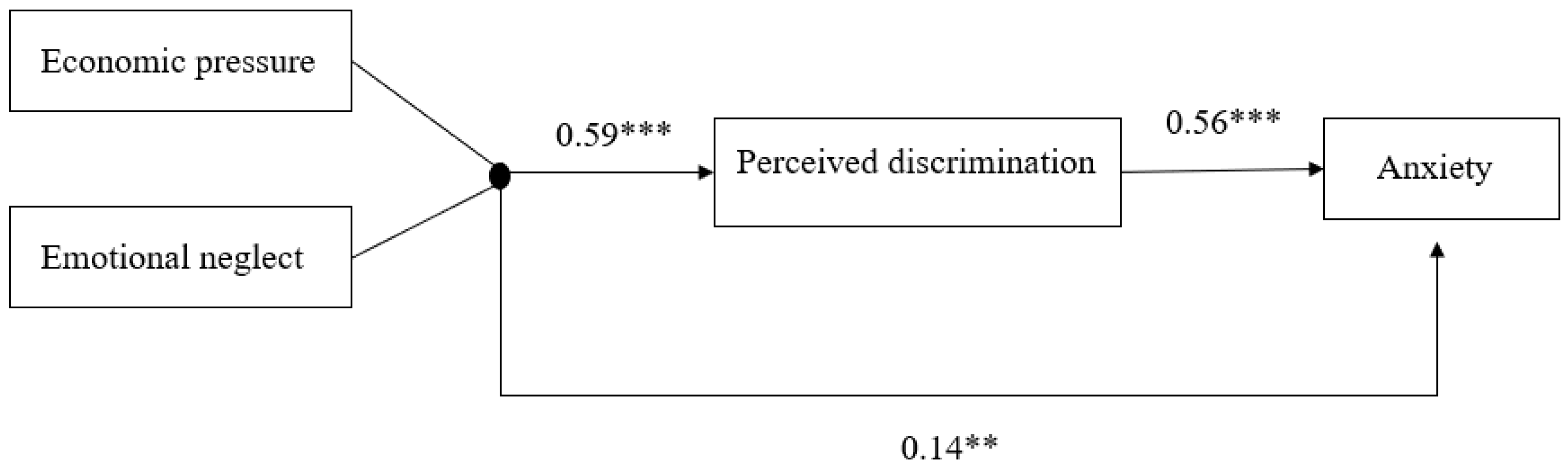

3.6. The Mediating Effect of Perceived Discrimination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ainsworth, M. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, V. R., & Lonigan, C. J. (2021). Trait anxiety and adolescent’s academic achievement: The role of executive function. Learning and Individual Differences, 85, 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleyard, K., Egeland, B., van Dulmen, M. H. M., & Sroufe, L. A. (2005). When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(3), 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaud, A. M., Brister, T. S., Duckworth, K., Foxworth, P., Fulwider, T., Suthoff, E. D., Werneburg, B., Aleksanderek, I., & Reinhart, M. L. (2022). Impact of major depressive disorder on comorbidities: A systematic literature review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 83(6), 43390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L., Beitchman, J., Gonzalez, A., Young, A., Wilson, B., Escobar, M., Chisholm, V., Brownlie, E., Khoury, J. E., Ludmer, J., & Villani, V. (2015). Cumulative risk, cumulative outcome: A 20-year longitudinal study. PLoS ONE, 10(6), e0127650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z., Chen, C., Zhang, W., Zhu, J., Jiang, Y., & Lai, X. (2016). Family economic hardship and Chinese adolescents’ sleep quality: A moderated mediation model involving perceived economic discrimination and coping strategy. Journal of Adolescence, 50, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagg, N., & Godfrey, E. (2018). Exploring parent-child relationships in alienated versus neglected/emotionally abused children using the Bene-Anthony Family Relations Test. Child Abuse Review, 27(6), 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bøe, T., Serlachius, A. S., Sivertsen, B., Petrie, K. J., & Hysing, M. (2017). Cumulative effects of negative life events and family stress on children’s mental health: The Bergen Child Study. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calaresi, D., Morese, R., Verrastro, V., & Saladino, V. (2025). Childhood emotional neglect, self-criticism, and meaning in life among adults living in therapeutic communities. Psicothema, 37(2), 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., & Sun, Y. H. (2015). Depression and anxiety among left-behind children in China: A systematic review. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(4), 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y., Pan, C., Tang, Q., Yuan, X., & Xiao, C. (2007). Development of child psychological abuse and neglect scale. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science, 2, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, G., & Feldman, S. I. (1996). Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1327–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J. R. (2007). Polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology. In C. Ostroff, & T. A. Judge (Eds.), Perspective on orgnizaional fit (pp. 209–258). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X., Fang, X., Zhao, X., & Chen, F. (2023). Cumulative contextual risk and social adjustment among left-behind children: The mediating role of stress and the moderating role of psychosocial resources. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 55(8), 1270–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellmeth, G., Rose-Clarke, K., Zhao, C., Busert, L. K., Zheng, Y., Massazza, A., Sonmez, H., Eder, B., Blewitt, A., Lertgrai, W., & Devakumar, D. (2018). Health impacts of parental migration on left-behind children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 392(10164), 2567–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., Zhang, S., Liao, X., Jia, Y., Yang, Y., & Zhang, W. (2024). Association between bullying victimization and mental health problems among Chinese left-behind children: A cross-sectional study from the adolescence mental health promotion cohort. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1440821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W., Xue, R., Chai, H., Sun, W., & Jiang, F. (2023). What matters on rural Left-Behind children’s problem behavior: Family socioeconomic status or perceived discrimination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X., Sun, J., Xiao, J., Wang, H., & Lin, D. (2022). The effect of parental perceived family stress on child problem behaviors: The mediating roles of parental psychological aggression and child cortisol response to stress. Psychological Development and Education, 5, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C., Tadesse, E., & Khalid, S. (2022). Family socioeconomic status and the parent-child relationship in Chinese adolescents: The multiple serial mediating roles of visual art activities. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovazolias, T. (2024). The relationship of rejection sensitivity to depressive symptoms in adolescence: The indirect effect of perceived social acceptance by peers. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidi, J., Lucente, M., Sonino, N., & Fava, G. A. (2020). Allostatic load and its impact on health: A systematic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 90(1), 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J. L., Shapero, B. G., Stange, J. P., Hamlat, E. J., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2013). Emotional maltreatment, peer victimization, and depressive versus anxiety symptoms during adolescence: Hopelessness as a mediator. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42(3), 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, K., Déchelotte, P., Ladner, J., & Tavolacci, M. P. (2019). Depression, anxiety stress and associated factors among university students in France. European Journal of Public Health, 29(Suppl. 4), ckz186.555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Hu, J., & Zhu, Y. (2022). The impact of perceived discrimination on mental health among Chinese migrant and left-behind children: A meta-analysis. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17(5), 2525–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humberg, S., Nestler, S., & Back, M. D. (2019). Response surface analysis in personality and social psychology: Checklist and clarifications for the case of congruence hypotheses. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J., Chen, J., & Chen, O. (2023). Are the relationships between mental health issues and being left-behind gendered in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 18(4), e0279278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, R. E., & Luxton, D. D. (2005). Vulnerability-stress models. Development of Psychopathology: A Vulnerability-Stress Perspective, 46(2), 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. U., Ulvenes, P. G., Øktedalen, T., & Hoffart, A. (2019). Psychometric properties of the general anxiety disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kealy, D., Laverdiere, O., Cox, D. W., & Hewitt, P. L. (2023). Childhood emotional neglect and depressive and anxiety symptoms among mental health outpatients: The mediating roles of narcissistic vulnerability and shame. Journal of Mental Health, 32(1), 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krahe, B., Abraham, C., Felber, J., & Helbig, M. K. (2005). Perceived discrimination of international visitors to universities in Germany and the UK. British Journal of Psychology, 96, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Monahan, P. O., & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, H., Zhang, Q., Li, X., Yang, H., Du, W., & Shao, J. (2019). Cumulative risk and problem behaviors among Chinese left-behind children: A moderated mediation model. School Psychology International, 40(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S. N., Isohanni, F., Granqvist, P., & Forslund, T. (2024). Attachment goes to court in Sweden: Perception and application of attachment concepts in child removal court decisions. Attachment & Human Development, 26(6), 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J., Liu, Y., Chen, S., Li, J., Wang, X., & Yu, B. (2023). The effects of family and school interpersonal relationships on left-behind children’s social adaptability: The chain-mediated role of self-esteem and life satisfaction. Journal of Southwest University Natural Science Edition, 45(12), 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Xu, Y., Sun, H., Yuan, Y., Lu, J., Jiang, J., & Liu, N. (2024). Associations between left-behind children’s characteristics and psychological symptoms: A cross-sectional study from China. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X., Xie, T., Li, W., Tao, Y., Liang, P., Zhao, Q., & Wang, J. (2023). The relationship between perceived discrimination and wellbeing in impoverished college students: A moderated mediation model of self-esteem and belief in a just world. Current Psychology, 42(8), 6711–6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., & Wu, G. (2022). The influence of family socioeconomic status on primary school students’ emotional intelligence: The mediating effect of parenting styles and regional differences. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 753774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamitsi-Puchner, A., & Briana, D. D. (2019). Economic stress and child health—The Greece experience. Acta Paediatrica, 108(10), 1740–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarik, A. S., & Conger, R. D. (2017). Stress and child development: A review of the Family Stress Model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S. (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(3), 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, E. A., & Smart, R. L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechtel, P., & Pizzagalli, D. A. (2011). Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: An integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology, 214(1), 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmes, T., & Branscombe, N. R. (2002). Influence of long-term racial environmental composition on subjective well-being in African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(3), 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, M. (1981). Stress, coping and development: Some issues and some questions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22(4), 323–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., & Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J., Hu, X., & Liu, X. (2009). Left-over children’s perceived discrimination: Its characteristics and relationship with personal well being. Journal of Henan University (Social Sciences), 6, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S., Li, X., Lin, D., Xu, X., & Zhu, M. (2013). Psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: The role of parental migration and parent-child communication. Child Care Health & Development, 39(2), 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (2001). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In M. A. Hogg, & D. Abrams (Eds.), Intergroup relations: Essential readings (pp. 94–109). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Z., Wang, Z., Lan, Y., Zhang, W., & Qiu, B. (2025). Socioeconomic status impacts Chinese late adolescents’ internalizing problems: Risk role of psychological insecurity and cognitive fusion. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teicher, M. H., & Samson, J. A. (2013). Childhood maltreatment and psychopathology: A case for ecophenotypic variants as clinically and neurobiologically distinct subtypes. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 1114–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Scheppingen, M. A., Chopik, W. J., Bleidorn, W., & Denissen, J. J. (2019). Longitudinal actor, partner, and similarity effects of personality on well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(4), e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, M. E., & Compas, B. E. (2002). Coping with family conflict and economic strain: The adolescent perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12(2), 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watamura, S. E., Phillips, D. A., Morrissey, T. W., McCartney, K., & Bub, K. (2011). Double jeopardy: Poorer social-emotional outcomes for children in the NICHD SECCYD experiencing home and child-care environments that confer risk. Child Development, 82(1), 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q., Zheng, H., Fan, Y., He, F., Quan, X., & Jiang, G. (2020). Perceived discrimination and loneliness and problem behaviors of left-behind junior high school students: The roles of teacher-student relationship and peer relationship. Psychology Science, 43(6), 1355–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Chen, S., Ye, Y., Wen, W., Zhen, R., & Zhou, X. (2025). Childhood neglect, depression, and academic burnout in left-behind children in China: Understanding the roles of feelings of insecurity and self-esteem. Child Protection and Practice, 5, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., Wang, Z., Sun, Q., Wang, D., Yin, X., & Li, Z. (2022). The relationship between cumulative family risk and emotional problems among impoverished children: A moderated mediation model. Psychology Development and Education, 38(1), 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y., Aibao, Z., & Manying, K. (2023). Family socioeconomic status and adolescent mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating roles of trait mindfulness and perceived stress. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Lu, K., Wang, Y., & Wang, L. (2025). The impact of cumulative family risk on the social adaptation of left-behind children: The chain mediation of teacher support and sense of self-worth. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Zhao, J., Ding, R., & Wang, M. (2024). The relationship between childhood trauma and romantic relationship satisfaction among Chinese university students: The mediating role of attachment and the moderating role of social support. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1519699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., & Zhen, R. (2022). How do physical and emotional abuse affect depression and problematic behaviors in adolescents? The roles of emotional regulation and anger. Child Abuse & Neglect, 129, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Gender | Age | Economic Pressure | Emotional Neglect | Perception of Discrimination | Anxiety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | |||||

| Age | 0.001 | 1 | ||||

| Economic pressure | −0.05 | 0.19 *** | 1 | |||

| Emotional neglect | −0.03 | 0.11 ** | 0.33 *** | 1 | ||

| Perception of discrimination | −0.03 | 0.19 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.49 *** | 1 | |

| Anxiety | 0.10 * | 0.18 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.64 *** | 1 |

| M ± SD | 14.67 ± 1.25 | 1.72 ± 0.81 | 1.15 ± 0.65 | 1.15 ± 0.73 | 1.05 ± 0.68 |

| Variable | Perception of Discrimination | Anxiety | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | p | Estimate | SE | p | |

| Intercept (b0) | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.153 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.108 |

| gender | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.06 | 0.992 |

| age | 0.10 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.002 |

| Economic pressure (b1) | 0.33 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.023 |

| Emotional neglect (b2) | 0.33 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.34 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Economic pressure2 (b3) | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.043 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.193 |

| Emotional neglect × Economic pressure (b4) | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.666 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.519 |

| Emotional neglect2 (b5) | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.327 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.877 |

| Slope of the Line of congruence (a1) | 0.65 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.48 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Curvature of the Line of congruence (a2) | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.588 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.071 |

| Slope of the line of incongruence (a3) | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.981 | −0.20 | 0.09 | 0.024 |

| Curvature of the Line of incongruence (a4) | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.453 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.759 |

| R2 | 0.23 *** | 0.35 *** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J. The Relationship Between Economic Pressure, Emotional Neglect and Anxiety Among Chinese Left-Behind Children: Based on Response Surface Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1679. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121679

Liao S, Wang D, Zhang K, Wang J. The Relationship Between Economic Pressure, Emotional Neglect and Anxiety Among Chinese Left-Behind Children: Based on Response Surface Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1679. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121679

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Suxia, Danyun Wang, Kuo Zhang, and Jingxin Wang. 2025. "The Relationship Between Economic Pressure, Emotional Neglect and Anxiety Among Chinese Left-Behind Children: Based on Response Surface Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1679. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121679

APA StyleLiao, S., Wang, D., Zhang, K., & Wang, J. (2025). The Relationship Between Economic Pressure, Emotional Neglect and Anxiety Among Chinese Left-Behind Children: Based on Response Surface Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1679. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121679