Episodic Memory, Chiari I Malformation, Personality and Coping: The Role of Chronic Pain

Abstract

1. Background/Aims

2. Introduction to Episodic Memory and Its Psychological Mechanisms

3. Episodic Memory: Emotional/Affective Context

4. A Neuroscience Model of Episodic Memory

5. Damasio’s Somatic Marker Hypothesis

6. Working Memory and Attention Modulation of Episodic Long-Term Memory

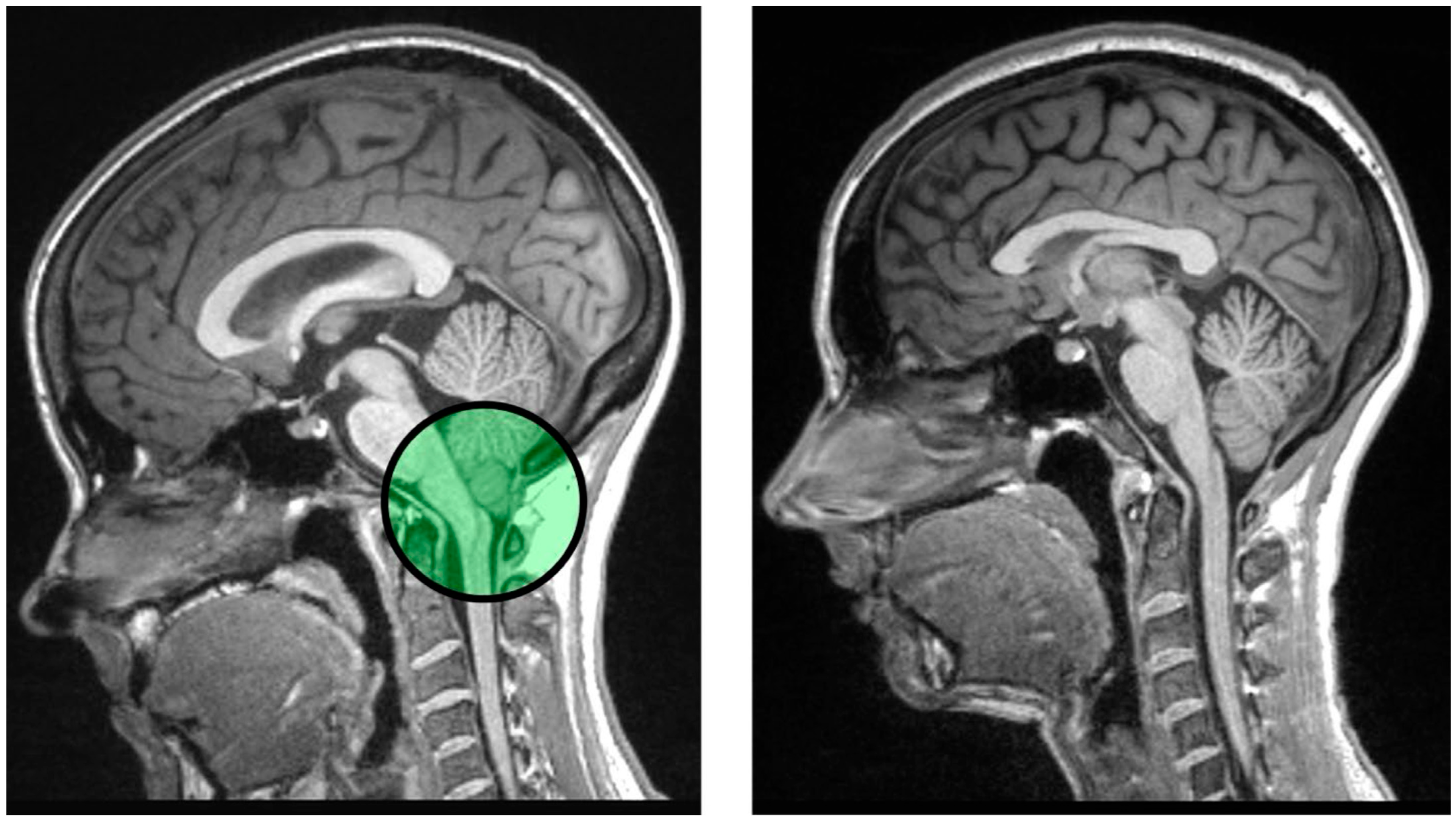

7. Chronic Pain as a Modulator of Episodic Memory and the Link to Chiari Malformation

8. Theoretical Application: Pathogenesis of Central Pain Sensitization in Chiari Malformation Type I

9. Individual Differences in Personality Can Modulate Episodic Memory

10. Affective Pain, Coping Mechanisms, and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

11. Chronic Pain Inhibition, Episodic Memory and Chiari Malformation Type I

12. The Role of Allostatic Load and Biological Resilience

13. Pharmacological Treatments for Pain and the Effect on Memory and Cognition

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexandra Kredlow, M., Fenster, R. J., Laurent, E. S., Ressler, K. J., & Phelps, E. A. (2022). Prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and threat processing: Implications for PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47(1), 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliaga, L., Hekman, K. E., Yassari, R., Straus, D., Luther, G., Chen, J., Sampat, A., & Frim, D. (2012). A novel scoring system for assessing Chiari malformation type I treatment outcomes. Neurosurgery, 70(3), 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. A., Delahanty, D., Kaut, K. P., Li, X., Garcia, M., Houston, J. R., Tokar, D. M., Loth, F., Maleki, J., Vorster, S., & Luciano, M. G. (2018). Chiari 1000 registry project: Assessment of surgical outcome on self-focused attention, pain, and delayed recall. Psychological Medicine, 48(10), 1634–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. A., Houston, J. R., Pollock, J. W., Buzzelli, C., Li, X., Harrington, A. K., Martin, B. A., Loth, F., Lien, M. C., Maleki, J., & Luciano, M. G. (2014). Task-specific and general cognitive effects in Chiari malformation type I. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e94844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. A., Hughes, M. L., Houston, J. R., Jardin, E., Mallik, P., McLennan, C., & Delahanty, D. L. (2019). Are there age differences in consolidated episodic memory? Experimental Aging Research, 45(2), 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. A., Kaut, K., Baena, E., Lien, M. C., & Ruthruff, E. (2011). Individual differences in positive affect moderate age-related declines in episodic long-term memory. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 23(6), 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. A., Kaut, K. P., Lord, R. G., Hall, R. J., Grabbe, J. W., & Bowie, T. (2005). An emotional mediation theory of differential age effects in episodic and semantic memories. Experimental Aging Research, 31(4), 355–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. A., Kaut, K. P., & Lord, R. R. (2008). Emotion and episodic memory. In Handbook of episodic memory. Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. A., Loth, F., Loth, D., Samman, M. M. A., Labuda, R., Herrera, C., Bapuraj, J. R., & Klinge, P. M. (2024). Correlation of anterior CSF space in the cervical spine with Chicago Chiari Outcome Scale score in adult females. Journal of Neurosurgery-Spine, 42(3), 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Samman, M. M., Garcia, M. A., Garcia, M., Houston, J. R., Loth, D., Labuda, R., Vorster, S., Klinge, P. M., Loth, F., Delahanty, D. L., & Allen, P. A. (2024). Relationship of morphometrics and symptom severity in female type I Chiari malformation patients with biological resilience. The Cerebellum, 23, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aly, M., & Turk-Browne, N. B. (2016). Attention promotes episodic encoding by stabilizing hippocampal representations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(4), E420–E429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barpujari, A., Kiley, A., Ross, J. A., & Veznedaroglu, E. (2023). A systematic review of non-opioid pain management in Chiari malformation (type 1) patients: Current evidence and novel therapeutic opportunities. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(9), 3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R. (2005). The Iowa gambling task and the somatic marker hypothesis: Some questions and answers. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(4), 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behroozi, Z., Jafarpour, M., Razmgir, M., Saffarpour, S., Azizi, H., Kheirandish, A., Kosari-rad, T., Ramezni, F., & Janzadeh, A. (2023). The effect of gabapentin and pregabalin administration on memory in clinical and preclinical studies: A meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T. R., Elman, J. A., Gustavson, D. E., Lyons, M. J., Fennema-Notestine, C., Williams, M. E., Panizzon, M. S., Pearce, R. C., Reynolds, C. A., Sanderson-Cimino, M., Toomey, R., Jak, A., Franz, C. E., & Kremen, W. S. (2025). History of chronic pain and opioid use is associated with cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 31(4), 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertossi, E., Aleo, F., Braghittoni, D., & Ciaramelli, E. (2016). Stuck in the here and now: Construction of fictitious and future experiences following ventromedial prefrontal damage. Neuropsychologia, 81, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, G. H. (1981). Mood and memory. American Psychologist, 36(2), 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R., & Kulik, J. (1977). Flashbulb memories. Cognition, 5(1), 73–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun, K. D., Christensen, R., Amris, K., Vaegter, H. B., Blichfeldt-Eckhardt, M. R., Bye-Moller, L., Holsgaard-Larsen, A., & Toft, P. (2024). Naltrexone 6 mg once daily versus placebo in women with fibromyalgia: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Rheumatology, 6(1), E31–E39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, R. (2001). Cognitive neuroscience of aging: Contributions of functional neuroimaging. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 42(3), 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, R. (2002). Hemispheric asymmetry reduction in older adults: The HAROLD model. Psychology and Aging, 17(1), 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, P., Markowitsch, H. J., Durwen, H. F., Widlitzek, H., Haupts, M., Holinka, B., & Gehlen, W. (1996). Right temporofrontal cortex as critical locus for the ecphory of old episodic memories. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 61(3), 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, R. R., Almeida, F. M., Martinez, A. M. B., & Freria, C. M. (2025). Neuroinflammation: Targeting microglia for neuroprotection and repair after spinal cord injury. Frontiers in Immunology, 16, 1670650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, B. P., Benedict, R. H., Lin, F., Roy, S., Federoff, H. J., & Mapstone, M. (2017). Personality and performance in specific neurocognitive domains among older persons. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(8), 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E. C., Fletcher, D. F., Stoodley, M. A., & Bilston, L. E. (2013a). Computational fluid dynamics modelling of cerebrospinal fluid pressure in Chiari malformation and syringomyelia. Journal of Biomechanics, 46(11), 1801–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E. C., Stoodley, M. A., & Bilston, L. E. (2013b). Changes in temporal flow characteristics of CSF in Chiari malformation type I with and without syringomyelia: Implications for theory of syrinx development Clinical article. Journal of Neurosurgery, 118(5), 1135–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corkin, S. (1984). Lasting consequences of bilateral medial temporal lobectomy: Clinical course and experimental findings in H.M. Seminars in Neurology, 4(2), 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, N. R., Kashikar-Zuck, S., & Coghill, R. C. (2019). Brain mechanisms impacted by psychological therapies for pain: Identifying targets for optimization of treatment effects. Pain Reports, 4(4), e767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. Grosset/Putnam. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. R., Graham, K. S., Xuereb, J. H., Williams, G. B., & Hodges, J. R. (2004). The human perirhinal cortex and semantic memory. European Journal of Neuroscience, 20(9), 2441–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demonet, J. F., Celsis, P., Nespoulous, J. L., Viallard, G., Marcvergnes, J. P., & Rascol, A. (1992). Cerebral blood-flow correlates of word monitoring in sentences—Influence of semantic incoherence—A spect study in normals. Neuropsychologia, 30(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Esposito, M. D., & Postle, B. R. (2002). The organization of working memory function in lateral prefrontal cortex: Evidence from event-related functional MRI. In D. T. Stuss, & R. T. Knight (Eds.), Principles of frontal lobe function (pp. 168–187). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dew, I. T. Z., & Cabeza, R. (2011). The porous boundaries between explicit and implicit memory: Behavioral and neural evidence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1224, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doberstein, C. A., Torabi, R., & Klinge, P. M. (2017). Current concepts in the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of type I Chiari malformations. Rhode Island Medical Journal (2013), 100(6), 47–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dowell, D., Ragan, K. R., Jones, C. M., Baldwin, G. T., & Chou, R. (2022). Prescribing opioids for pain—The new CDC clinical practice guideline. New England Journal of Medicine, 387(22), 2011–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, R. H., Turk, D. C., Revicki, D. A., Harding, G., Coyne, K. S., Peirce-Sandner, S., Bhagwat, D., Everton, D., Burke, L. B., Cowan, P., & Farrar, J. T. (2009). Development and initial validation of an expanded and revised version of the Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2). Pain, 144(1–2), 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccleston, C., & Crombez, G. (1999). Pain demands attention: A cognitive-affective model of the interruptive function of pain. Psychological Bulletin, 125(3), 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppelheimer, M. S., Houston, J. R., Bapuraj, J. R., Labuda, R., Loth, D. M., Braun, A. M., Allen, N. J., Heidari Pahlavian, S., Biswas, D., Urbizu, A., Martin, B. A., Maher, C. O., Allen, P. A., & Loth, F. (2018). A retrospective 2D morphometric analysis of adult female Chiari type I patients with commonly reported and related conditions. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabri, T. L., Datta, R., O’Mahony, J., Barlow-Krelina, E., De Somma, E., Longoni, G., Gur, R. E., Gur, R. C., Bacchus, M., Yeh, E. A., Banwell, B. L., & Till, C. (2021). Memory, processing of emotional stimuli, and volume of limbic structures in pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage-Clinical, 31, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischbein, R., Saling, J. R., Marty, P., Kropp, D., Meeker, J., Amerine, J., & Chyatte, M. R. (2015). Patient-reported Chiari malformation type I symptoms and diagnostic experiences: A report from the national Conquer Chiari Patient Registry database. Neurological Sciences, 36(9), 1617–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedlander, R. M. (2024). Congenital and acquired Chiari syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 390(23), 2191–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M., Amayra, I., Lazaro, E., Lopez-Paz, J. F., Martinez, O., Perez, M., Berrocoso, S., & Al-Rashaida, M. (2018a). Comparison between decompressed and non-decompressed Chiari malformation type I patients: A neuropsychological study. Neuropsychologia, 121, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M., Amayra, I., Pérez, M., Salgueiro, M., Martínez, O., López-Paz, J. F., & Allen, P. A. (2024). Cognition in Chiari malformation type I: An update of a systematic review. Neuropsychology Review, 34(3), 952–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M., Eppelheimer, M. S., Houston, J. R., Houston, M. L., Nwotchouang, B. S. T., Kaut, K. P., Labuda, R., Bapuraj, J. R., Maleki, J., Klinge, P. M., Vorster, S., Luciano, M. G., Loth, F., & Allen, P. A. (2022). Adult age differences in self-reported pain and anterior CSF space in Chiari malformation. Cerebellum, 21(2), 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M., Lazaro, E., Lopez-Paz, J. F., Martinez, O., Perez, M., Berrocoso, S., Al-Rashaida, M., & Amayra, I. (2018b). Cognitive functioning in Chiari malformation type I without posterior fossa surgery. Cerebellum, 17(5), 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. A., Allen, P. A., Li, X., Houston, J. R., Loth, F., Labuda, R., & Delahanty, D. L. (2019). An examination of pain, disability, and the psychological correlates of Chiari malformation pre- and post-surgical correction. Disability and Health Journal, 12(4), 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M. A., Li, X., Allen, P. A., Delahanty, D. L., Eppelheimer, M. S., Houston, J. R., Johnson, D. M., Loth, F., Maleki, J., Vorster, S., & Luciano, M. G. (2021). Impact of surgical status, loneliness, and disability on interleukin 6, C-reactive protein, cortisol, and estrogen in females with symptomatic type I Chiari malformation. The Cerebellum, 20(6), 872–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. A., Rabinowitz, E. P., Levin, M. E., Shasteen, H., Allen, P. A., & Delahanty, D. L. (2023). Online acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain in a sample of people with Chiari malformation: A pilot study. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, 33(3), 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholampour, S., & Gholampour, H. (2020). Correlation of a new hydrodynamic index with other effective indexes in Chiari I malformation patients with different associations. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 15907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholampour, S., & Taher, M. (2018). Relationship of morphologic changes in the brain and spinal cord and disease symptoms with cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamic changes in patients with Chiari malformation type I. World Neurosurgery, 116, e830–e839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanzer, M. (1972). Storage mechanisms in recall. In G. H. Bower, & J. T. Spence (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 5, pp. 129–193). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, A. (2015). Is atlantoaxial instability the cause of Chiari malformation? Outcome analysis of 65 patients treated by atlantoaxial fixation. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine, 22, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A., Jadhav, D., Shah, A., Rai, S., Dandpat, S., Vutha, R., Dhar, A., & Prasad, A. (2020). Chiari 1 formation redefined-clinical and radiographic observations in 388 surgically treated patients. World Neurosurgery, 141, e921–e934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, P., Malik, B. H., & Hussain, M. L. (2019). Noninvasive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in chronic refractory pain: A systematic review. Cureus, 11(10), e6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S. C., Villatte, M., Levin, M., & Hildebrandt, M. (2011). Open, aware, and active: Contextual approaches as an emerging trend in the behavioral and cognitive therapies. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiss, J. D. (2023). Cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamics in Chiari I malformation and syringomyelia: Modeling pathophysiology. Neurosurgery Clinics of North America, 34(1), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, J. R., & Patterson, K. (1997). Semantic memory disorders. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 1(2), 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J. R., Allen, P. A., Rogers, J. M., Lien, M. C., Allen, N. J., Hughes, M. L., Bapuraj, J. R., Eppelheimer, M. S., Loth, F., Stoodley, M. A., Vorster, S. J., & Luciano, M. G. (2019). Type I Chiari malformation, RBANS performance, and brain morphology: Connecting the dots on cognition and macrolevel brain structure. Neuropsychology, 33(5), 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, J. R., Eppelheimer, M. S., Pahlavian, S. H., Biswas, D., Urbizu, A., Martin, B. A., Bapuraj, J. R., Luciano, M., Allen, P. A., & Loth, F. (2018). A morphometric assessment of type I Chiari malformation above the McRae line: A retrospective case-control study in 302 adult female subjects. Journal of Neuroradiology, 45(1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houston, J. R., Hughes, M. L., Bennett, I. J., Allen, P. A., Rogers, J. M., Lien, M. C., Stoltz, H., Sakaie, K., Loth, F., Maleki, J., Vorster, S. J., & Luciano, M. G. (2020). Evidence of neural microstructure abnormalities in type I Chiari malformation: Associations among fiber tract integrity, pain, and cognitive dysfunction. Pain Medicine, 21(10), 2323–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houston, J. R., Maleki, J., Loth, F., Klinge, P. M., & Allen, P. A. (Eds.). (2022). Influence of pain on cognitive dysfunction and emotion dysregulation in Chiari malformation type I. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, M. L., Houston, J. R., Sakaie, K., Klinge, P. M., Vorster, S., Luciano, M., Loth, F., & Allen, P. A. (2021). Functional connectivity abnormalities in type I Chiari: Associations with cognition and pain. Brain Communications, 3(3), fcab137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Zhang, Y., Ma, L., Wu, B., Feng, J., Cheng, W., & Yu, J. (2025). Neuroticism is associated with future disease and mortality risks. Chinese Medical Journal, 138(11), 1355–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimy, A., Wu, T. X., Mack, J., Scott, G. C., Cortes, M. X., Cantor, F. K., Loth, F., & Heiss, J. D. (2023). Prospective, longitudinal study of clinical outcome and morphometric posterior fossa changes after craniocervical decompression for symptomatic Chiari I malformation. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 44(10), 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, M., Mori, E., Hirono, N., Imamura, T., Shimomura, T., Ikejiri, Y., & Yamashita, H. (1998). Amnestic people with Alzheimer’s disease who remembered the Kobe earthquake. British Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juster, R. P., McEwen, B. S., & Lupien, S. J. (2010). Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, A., Karbasian, N., Rabiei, P., Cano, A., Riascos, R. F., Tandon, N., Arevalo, O., Ocasio, L., Younes, K., Khayat-khoei, M., Mirbagheri, S., & Hasan, K. M. (2018). Revealing the cerebello-ponto-hypothalamic pathway in the human brain. Neuroscience Letters, 677, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, A., Milosavljevic, S., Gandhi, A., Lano, K. R., Shobeiri, P., Sherbaf, F. G., Sair, H. I., Riascos, R. F., & Hasan, K. M. (2023). The Cortico-Limbo-Thalamo-Cortical circuits: An update to the original papez circuit of the human limbic system. Brain Topography, 36(3), 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, N., Ellison, D., Parkin, A. J., Hunkin, N. M., Burrows, E., Sampson, S. A., & Morrison, E. A. (1994). Bilateral temporal-lobe pathology with sparing of medial temporal-lobe structures—Lesion profile and pattern of memory disorder. Neuropsychologia, 32(1), 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartsounis, L. D., Rudge, P., & Stevens, J. M. (1995). Bilateral lesions of Ca1 and Ca2 fields of the hippocampus are sufficient to cause a severe amnesic syndrome in humans. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 59(1), 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempen, G. I., Jelicic, M., & Ormel, J. (1997). Personality, chronic medical morbidity, and health-related quality of life among older persons. Health Psychology, 16(6), 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kensinger, E. A. (2009). Emotional memory across the adult lifespan. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, L., & Cahill, L. (2003). Amygdala modulation of parahippocampal and frontal regions during emotionally influenced memory storage. Neuroimage, 20(4), 2091–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaming, R., Veltman, D. J., & Comijs, H. C. (2017). The impact of personality on memory function in older adults-results from the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(7), 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klinge, P. M., McElroy, A., Donahue, J. E., Brinker, T., Gokaslan, Z. L., & Beland, T. B. (2021). Abnormal spinal cord motion at the craviocervical junction in hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos patients. Journal of Neurosurgery-Spine, 35(1), 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaBar, K. S., & Cabeza, R. (2006). Cognitive neuroscience of emotional memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7(1), 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBar, K. S., & Phelps, E. A. (1998). Arousal-mediated memory consolidation: Role of the medial temporal lobe in humans. Psychological Science, 9(6), 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labuda, R., Loth, D., Allen, P. A., & Loth, F. (2022a). Factors associated with patient-reported postsurgical symptom improvement in adult females with Chiari malformation type I: A report from the Chiari1000 dataset. World Neurosurgery, 161, e682–e687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labuda, R., Nwotchouang, B. S. T., Ibrahimy, A., Allen, P. A., Oshinski, J. N., Klinge, P., & Loth, F. (2022b). A new hypothesis for the pathophysiology of symptomatic adult Chiari malformation type I. Medical Hypotheses, 158, 110740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, L. K., & Madden, D. J. (2000). Functional neuroimaging of memory: Implications for cognitive aging. Microscopy Research and Technique, 51(1), 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigland, L. A., Schulz, L. E., & Janowsky, J. S. (2004). Age related changes in emotional memory. Neurobiology of Aging, 25(8), 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, J. R., & Limbrick, D. D., Jr. (2015). Chiari I malformation: Adult and pediatric considerations. Neurosurgery Clinics of North America, 26(4), xiii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, V., Magnussen, J. S., Stoodley, M. A., & Bilston, L. E. (2016). Cerebellar and hindbrain motion in Chiari malformation with and without syringomyelia. Journal of Neurosurgery-Spine, 24(4), 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levenson, R. W., Carstensen, L. L., & Gottman, J. M. (1994). The influence of age and gender on affect, physiology, and their interrelations—A study of long-term marriages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(1), 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenson, R. W., Friesen, W. V., Ekman, P., & Carstensen, L. L. (1991). Emotion, physiology, and expression in old-age. Psychology and Aging, 6(1), 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T., Barash, J. A., Wang, S., Li, F., Yang, Z., Kofke, W. A., Sha, F., & Tang, J. (2025). Regular use of opioids and dementia, cognitive measures, and neuroimaging outcomes among UK Biobank participants with chronic non-cancer pain. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 21(5), e70177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, V. M., Daniels, D. J., Haile, D. T., & Ahn, E. S. (2021). Effects of intraoperative liposomal bupivacaine on pain control and opioid use after pediatric Chiari I malformation surgery: An initial experience. Journal of Neurosurgery-Pediatrics, 27(1), 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchetti, M., Terracciano, A., Stephan, Y., & Sutin, A. R. (2016). Personality and cognitive decline in older adults: Data from a longitudinal sample and meta-analysis. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(4), 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, E. J., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2013). Episodic and autobiographical memory. In A. F. Healy, R. W. Proctor, & I. B. Weiner (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Experimental psychology (2nd ed., pp. 472–494). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, C., Ciaramelli, E., De Luca, F., & Maguire, E. A. (2018). Comparing and contrasting the cognitive effects of hippocampal and ventromedial prefrontal cortex damage: A review of human lesion studies. Neuroscience, 374, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T., & Martin, T. A. (2005). The NEO-PI-3: A more readable revised NEO Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 84(3), 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, A., Rashmir, A., Manfredi, J., Sledge, D., Carr, E., Stopa, E., & Klinge, P. (2019). Evaluation of the structure of myodural bridges in an equine model of ehlers-danlos syndromes. Scientific Reports, 9, 9978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S., & Alves, S. E. (1999). Estrogen actions in the central nervous system. Endocrine Reviews, 20(3), 279–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S., & Seeman, T. (1999). Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress—Elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Socioeconomic Status and Health in Industrial Nations, 896, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S., & Stellar, E. (1993). Stress and the individual: Mechanisms leading to disease. Archives of Internal Medicine, 153(18), 2093–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaugh, J. L. (2000). Memory—A century of consolidation. Science, 287(5451), 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilandt, W. J., Barea-Rodriguez, E., Harvey, S. A. K., & Martinez, J., Jr. (2004). Role of hippocampal CA3 μ-opioid receptors in spatial learning and memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 24(12), 2953–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, B., Winocur, G., & Moscovitch, M. (1999). False recall and false recognition: An examination of the effects of selective and combined lesions to the medial temporal lobe diencephalon and frontal lobe structures. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 16(3–5), 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzack, R., & Wall, P. D. (1965). Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science, 150(3699), 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendell, L. M. (2014). Constructing and deconstructing the gate theory of pain. Pain, 155(2), 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V. (2023). 20 years of the default mode network: A review and synthesis. Neuron, 111(16), 2469–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V., Boyett-Anderson, J. M., Schatzberg, A. F., & Reiss, A. L. (2002). Relating semantic and episodic memory systems. Cognitive Brain Research, 13(2), 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milhorat, T. H., Chou, M. W., Trinidad, E. M., Kula, R. W., Mandell, M., Wolpert, C., & Speer, M. C. (1999). Chiari I malformation redefined: Clinical and radiographic findings for 364 symptomatic patients. Neurosurgery, 44(5), 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzer, M. Z., Correia, C. J., & Strain, E. C. (2004). A dose-effect study of repeated administration of buprenorphine/naloxone on performance in opioid-dependent volunteers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 74(2), 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A., Bidonde, J., Fisher, E., Häuser, W., Bell, R. F., Perrot, S., Makri, S., & Straube, S. (2025). Effectiveness of pharmacological therapies for fibromyalgia syndrome in adults: An overview of cochrane reviews. Rheumatology, 64(5), 2385–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadel, L., & Moscovitch, M. (1998). Hippocampal contributions to cortical plasticity. Neuropharmacology, 37(4–5), 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noseda, R., Melo-Carrillo, A., Nir, R.-R., Strassman, A. M., & Burstein, R. (2019). Non-trigeminal nociceptive innervation of the posterior dura: Implications to occipital headache. The Journal of Neuroscience, 39(10), 1867–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, J., Elhabal, A., Tsermoulas, G., & Flint, G. (2021). Symptom outcome after craniovertebral decompression for Chiari type 1 malformation without syringomyelia. Acta Neurochirurgica, 163(1), 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, S. E., Fox, P. T., Posner, M. I., Mintun, M., & Raichle, M. E. (1988). Positron emission tomographic studies of the cortical anatomy of single-word processing. Nature, 331(6157), 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L. R., & Peterson, M. J. (1959). Short-term retention of individual verbal items. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, M. I., Petersen, S. E., Fox, P. T., & Raichle, M. E. (1988). Localization of cognitive operations in the human-brain. Science, 240(4859), 1627–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, E. P., Ripley, G., Levin, M. E., Allen, P. A., & Delahanty, D. L. (2024). Limited effects of phone coaching in an RCT of online self-guided acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 34, 100828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J. M., & Squire, L. R. (1997). Impaired recognition memory in patients with lesions limited to the hippocampal formation. Behavioral Neuroscience, 111(4), 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J. M., & Squire, L. R. (1998). Retrograde amnesia for facts and events: Findings from four new cases. Journal of Neuroscience, 18(10), 3943–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RempelClower, N. L., Zola, S. M., Squire, L. R., & Amaral, D. G. (1996). Three cases of enduring memory impairment after bilateral damage limited to the hippocampal formation. Journal of Neuroscience, 16(16), 5233–5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J. M., Savage, G., & Stoodley, M. A. (2018). A systematic review of cognition in Chiari I malformation. Neuropsychology Review, 28(2), 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M. (1996). Rey auditory verbal learning test: RAVLT: A handbook. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, S. C., Streese, C. D., Manzel, K., Kamm, J., Menezes, A. H., Tranel, D., & Dlouhy, B. J. (2021). Cognitive and psychological functioning in Chiari malformation type I before and after surgical decompression—A prospective cohort study. Neurosurgery, 89(6), 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira-Lichter, I., Oren, N., Jacob, Y., Gruberger, M., & Hendler, T. (2013). Portraying the unique contribution of the default mode network to internally driven mnemonic processes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(13), 4950–4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharot, T., Delgado, M. R., & Phelps, E. A. (2004). How emotion enhances the feeling of remembering. Nature Neuroscience, 7(12), 1376–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., Rao, R., Chatterjee, B., Mishra, A. K., Kaloiya, G., & Ambekar, A. (2021). Cognitive functioning in patients maintained on buprenorphine at peak and trough buprenorphine levels: An experimental study. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 61, 102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinella, S., & McCarthy, R. (2024). Buprenorphine for pain: A narrative review and practical applications. The American Journal of Medicine, 137(5), 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, L. R. (2004). Memory systems of the brain: A brief history and current perspective. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 82(3), 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, L. R., & Zolamorgan, S. (1991). The medial temporal-lobe memory system. Science, 253(5026), 1380–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, E., & Squire, L. R. (1999). Memory for places learned long ago is intact after hippocampal damage. Nature, 400(6745), 675–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyler, T. J., & Discenna, P. (1986). The hippocampal memory indexing theory. Behavioral Neuroscience, 100(2), 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokar, D. M., Kaut, K. P., & Allen, P. A. (2023). Revisiting the factor structure of the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire-2 (SF-MPQ-2): Evidence for a bifactor model in individuals with Chiari malformation. PLoS ONE, 18(10), e0287208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(2), 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, I. A., Guiomar, R., Carvalho, S. A., Duarte, J., Lapa, T., Menezes, P., Nogueira, M. R., Patrao, B., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Castilho, P. (2021). Efficacy of online-based acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Pain, 22(11), 1328–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulving, E. (1983). Elements of episodic memory. In Oxford psychology series no. 2. Clarendon. Available online: https://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0637/82008241-t.html (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Tulving, E. (1985). Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne, 26(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VarghaKhadem, F., Gadian, D. G., Watkins, K. E., Connelly, A., VanPaesschen, W., & Mishkin, M. (1997). Differential effects of early hippocampal pathology on episodic and semantic memory. Science, 277(5324), 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veehof, M. M., Trompetter, H. R., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & Schreurs, K. M. G. (2016). Acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A meta-analytic review. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 45(1), 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. J., Sun, Y. P., & Zhang, D. F. (2016). Association between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and cognitive decline: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Drugs & Aging, 33(7), 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Y., Ye, X., Song, B., Yan, Y. X., Ma, W. Y., & Shi, J. P. (2023). Features of event-related potentials during retrieval of episodic memory in patients with mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17, 1185228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, N. S., Hanson, A. C., Schulte, P. J., Habermann, E. B., Warner, D. O., & Mielke, M. M. (2022). Prescription opioids and longitudinal changes in cognitive function in older adults: A population-based observational study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(12), 3526–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicksell, R. K., Kemani, M., Jensen, K., Kosek, E., Kadetoff, D., Sorjonen, K., Ingvar, M., & Olsson, G. L. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy for fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Pain, 17(4), 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D. A., Johnson, K., Garton, H. J., Muraszko, K. M., & Maher, C. O. (2017). Trends in surgical treatment of Chiari malformation type I in the United States. Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 19(2), 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. S., Krueger, K. R., Gu, L. P., Bienias, J. L., De Leon, C. F. M., & Evans, D. A. (2005). Neuroticism, extraversion, and mortality in a defined population of older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67(6), 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Bauer, B. A., Wahner-Roedler, D. L., Chon, T. Y., & Xiao, L. (2020). The modified WHO analgesic ladder: Is it appropriate for chronic non-cancer pain? Journal of Pain Research, 13, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarbrough, C. K., Greenberg, J. K., Smyth, M. D., Leonard, J. R., Park, T. S., & Limbrick, D. D. (2014). External validation of the Chicago Chiari Outcome Scale clinical article. Journal of Neurosurgery-Pediatrics, 13(6), 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allen, P.A.; Kaut, K.P.; Houston, J.R.; Houston, M.L.; Rabinowitz, E.P.; Delahanty, D.L.; Klinge, P.M. Episodic Memory, Chiari I Malformation, Personality and Coping: The Role of Chronic Pain. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121678

Allen PA, Kaut KP, Houston JR, Houston ML, Rabinowitz EP, Delahanty DL, Klinge PM. Episodic Memory, Chiari I Malformation, Personality and Coping: The Role of Chronic Pain. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121678

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllen, Philip A., Kevin P. Kaut, James R. Houston, Michelle L. Houston, Emily P. Rabinowitz, Douglas L. Delahanty, and Petra M. Klinge. 2025. "Episodic Memory, Chiari I Malformation, Personality and Coping: The Role of Chronic Pain" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121678

APA StyleAllen, P. A., Kaut, K. P., Houston, J. R., Houston, M. L., Rabinowitz, E. P., Delahanty, D. L., & Klinge, P. M. (2025). Episodic Memory, Chiari I Malformation, Personality and Coping: The Role of Chronic Pain. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121678