Wastewater Analyses for Psychoactive Substances at Music Festivals: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychoactive and Illicit Drugs

1.2. Wastewater Analysis for Psychoactive Substances

1.3. Psychoactive Substances at Music Festivals

1.4. The Potential of Wastewater Analyses for Psychoactive Substances at Music Festivals

1.5. Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Research in humans;

- Either a meta-analysis or an original article (generating new research data);

- Research on wastewater analyses for drugs during/after music festivals, which means that music was the main feature of the festival;

- Published in English, German, or Romanian.

- Case reports and case studies;

- Animal and cell studies;

- Review articles;

- Perspective papers;

- Letters (without data);

- Master or doctoral theses.

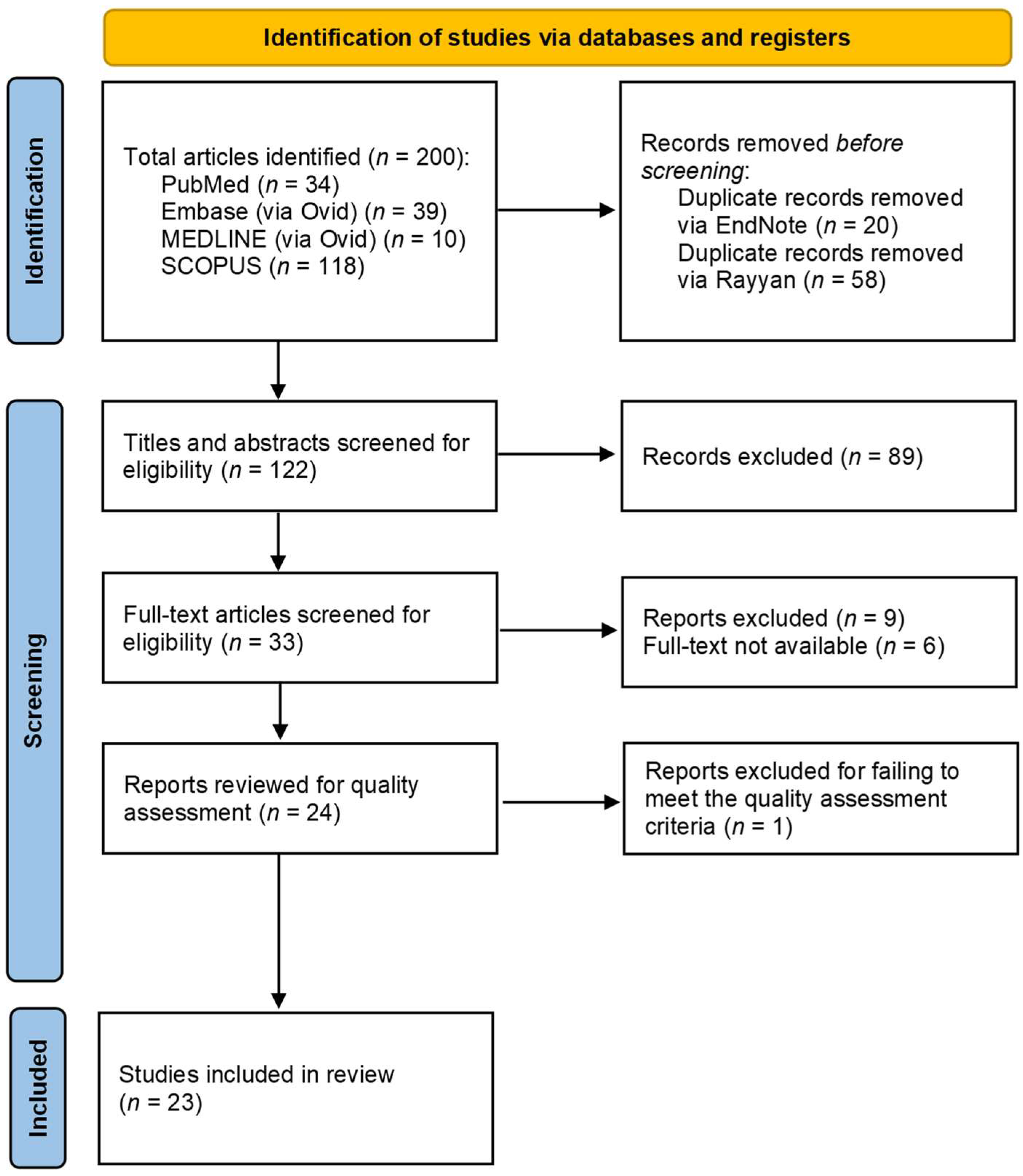

2.3. Screening/Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Study Results

3.3.1. Sampling Methods

3.3.2. Analytical Methods

3.3.3. Drug Preferences and Patterns

3.3.4. Music Genre–Drug Associations

3.3.5. Regional Patterns in Festival Drug Consumption

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Results

4.1.1. Sampling Methodologies and Analytical Approaches

4.1.2. Substance Detection Patterns, Geographic Variations, and Festival Characteristics

4.1.3. Public Health and Harm Reduction Applications

4.2. Limitations

4.2.1. Limitations of This Systematic Review

4.2.2. Geographic Representation and Global Applicability

4.2.3. Demographic Representation, Epidemiology and Gender Bias

4.2.4. Sampling Challenges

4.2.5. Analytical Methodology and Technical Constraints

4.2.6. Data Interpretation Challenges

4.2.7. Study Design and Cross-Study Comparability Issues

4.2.8. Risk of Bias

4.2.9. Causes of Heterogeneity

4.3. Implications and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aberg, D., Chaplin, D., Freeman, C., Paizs, B., & Dunn, C. (2022). The environmental release and ecosystem risks of illicit drugs during Glastonbury Festival. Environmental Research, 204, 112061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APA Dictionary of Psychology. (n.d.). Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Archer, J. R. H., Dargan, P. I., Lee, H. M. D., Hudson, S., & Wood, D. M. (2014). Trend analysis of anonymised pooled urine from portable street urinals in central London identifies variation in the use of novel psychoactive substances. Clinical Toxicology, 52(3), 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, R., Huchthausen, J., Huber, C., Dewapriya, P., Tscharke, B. J., Verhagen, R., Puljevic, C., Escher, B. I., & O’Brien, J. W. (2024). Improving wastewater-based epidemiology for new psychoactive substance surveillance by combining a high-throughput in vitro metabolism assay and LC−HRMS metabolite identification. Water Research, 253, 121297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, R., White, J. M., Nguyen, L., Pandopulos, A. J., & Gerber, C. (2020). What is the drug of choice of young festivalgoers? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 216, 108315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaglia, L., Udrisard, R., Bannwarth, A., Gibson, A., Béen, F., Lai, F. Y., Esseiva, P., & Delémont, O. (2020). Testing wastewater from a music festival in Switzerland to assess illicit drug use. Forensic Science International, 309, 110148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berset, J.-D., Brenneisen, R., & Mathieu, C. (2010). Analysis of llicit and illicit drugs in waste, surface and lake water samples using large volume direct injection high performance liquid chromatography—Electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS). Chemosphere, 81(7), 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlsma, L., Celma, A., Castiglioni, S., Salgueiro-González, N., Bou-Iserte, L., Baz-Lomba, J. A., Reid, M. J., Dias, M. J., Lopes, A., Matias, J., Pastor-Alcañiz, L., Radonić, J., Turk Sekulic, M., Shine, T., Van Nuijs, A. L. N., Hernandez, F., & Zuccato, E. (2020). Monitoring psychoactive substance use at six European festivals through wastewater and pooled urine analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 725, 138376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlsma, L., Serrano, R., Ferrer, C., Tormos, I., & Hernández, F. (2014). Occurrence and behavior of illicit drugs and metabolites in sewage water from the Spanish Mediterranean coast (Valencia region). Science of the Total Environment, 487, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodík, I., Mackuľak, T., Fáberová, M., & Ivanová, L. (2016). Occurrence of illicit drugs and selected pharmaceuticals in Slovak municipal wastewater. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23(20), 21098–21105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandeburová, P., Bodík, I., Horáková, I., Žabka, D., Castiglioni, S., Salgueiro-González, N., Zuccato, E., Špalková, V., & Mackuľak, T. (2020). Wastewater-based epidemiology to assess the occurrence of new psychoactive substances and alcohol consumption in Slovakia. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 200, 110762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brett, J., Siefried, K. J., Healey, A., Harrod, M. E., Franklin, E., Barratt, M. J., Masters, J., Nguyen, L., Adiraju, S., & Gerber, C. (2022). Wastewater analysis for psychoactive substances at music festivals across New South Wales, Australia in 2019–2020. Clinical Toxicology, 60(4), 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Music festival. In Cambridge dictionary. Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/music-festival (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Devault, D. A., Peyré, A., Jaupitre, O., Daveluy, A., & Karolak, S. (2020). The effect of the Music Day event on community drug use. Forensic Science International, 309, 110226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embase. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.embase.com/landing?status=grey (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- EMCDDA. (2016). Recent changes in Europe’s MDMA/ecstasy market. EMCDDA rapid communication [Report]. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/25469/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- EMCDDA (Ed.). (2017). European drug report 2017: Trends and developments. Publications Office. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). (2025). Good manufacturing practice. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/compliance/good-manufacturing-practice (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Fiorentini, A., Cantù, F., Crisanti, C., Cereda, G., Oldani, L., & Brambilla, P. (2021). Substance-induced psychoses: An updated literature review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 694863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuens, M., Van Hoofstadt, K., Hoogmartens, O., Van den Eede, N., & Sabbe, M. (2022). Pooled urine analysis at a belgian music festival: Trends in alcohol consumption and recreational drug use. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 37(6), 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjerde, H., Gjersing, L., Baz-Lomba, J. A., Bijlsma, L., Salgueiro-González, N., Furuhaugen, H., Bretteville-Jensen, A. L., Hernández, F., Castiglioni, S., Johanna Amundsen, E., & Zuccato, E. (2019). Drug use by music festival attendees: A novel triangulation approach using self-reported data and test results of oral fluid and pooled urine samples. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(14), 2317–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C. S., de Jesus Soares Freire, D., de Souza Ramos Pontes Moura, H., Maldaner, A. O., Pinheiro, F. A. S. D., Ferreira, G. L. R., de Oliveira Miranda, M. L., Ferreira, L. D. S., Murga, F. G., Sodré, F. F., & Aragão, C. F. S. (2025). Wastewater surveillance to assess cocaine and methylenedioxymethamphetamine use trends during a major music festival in Brazil. Drug Testing and Analysis, 17(1), 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia-Lor, E., Castiglioni, S., Bade, R., Been, F., Castrignanò, E., Covaci, A., González-Mariño, I., Hapeshi, E., Kasprzyk-Hordern, B., Kinyua, J., Lai, F. Y., Letzel, T., Lopardo, L., Meyer, M. R., O’Brien, J., Ramin, P., Rousis, N. I., Rydevik, A., Ryu, Y., … Bijlsma, L. (2017). Measuring biomarkers in wastewater as a new source of epidemiological information: Current state and future perspectives. Environment International, 99, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, L., & Hughes, A. (1997). The validity of self-reported drug use: Improving the accuracy of survey estimates. NIDA Research Monograph, 167, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hoegberg, L. C. G., Christiansen, C., Soe, J., Telving, R., Andreasen, M. F., Staerk, D., Christrup, L. L., & Kongstad, K. T. (2018). Recreational drug use at a major music festival: Trend analysis of anonymised pooled urine. Clinical Toxicology, 56(4), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, M. (2005). Young people and illicit drug use in Australia [Working Paper]. National Centre in HIV Social Research, The University of New South Wales. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houck, M. M., & Siegel, J. A. (2010). Illicit drugs. In Fundamentals of forensic science (pp. 305–340). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI Critical Appraisal Tool. (n.d.). Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Jiang, J.-J., Lee, C.-L., Fang, M.-D., Tu, B.-W., & Liang, Y.-J. (2015). Impacts of emerging contaminants on surrounding aquatic environment from a youth festival. Environmental Science & Technology, 49(2), 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P. B., & Richter, L. (2004). Research note: What if we’re wrong? Some possible implications of systematic distortions in adolescents’ self-reports of sensitive behaviors. Journal of Drug Issues, 34(4), 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T., & Fendrich, M. (2005). Modeling sources of self-report bias in a survey of drug use epidemiology. Annals of Epidemiology, 15(5), 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. P. (2014). Sources of error in substance use prevalence surveys. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2014, 923290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinghorn, A. D., Pan, L., Fletcher, J. N., & Chai, H. (2011). The relevance of higher plants in lead compound discovery programs. Journal of Natural Products, 74(6), 1539–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinyua, J., Negreira, N., Miserez, B., Causanilles, A., Emke, E., Gremeaux, L., de Voogt, P., Ramsey, J., Covaci, A., & van Nuijs, A. L. N. (2016). Qualitative screening of new psychoactive substances in pooled urine samples from Belgium and United Kingdom. Science of the Total Environment, 573, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F. Y., Thai, P. K., O’Brien, J., Gartner, C., Bruno, R., Kele, B., Ort, C., Prichard, J., Kirkbride, P., Hall, W., Carter, S., & Mueller, J. F. (2013). Using quantitative wastewater analysis to measure daily usage of conventional and emerging illicit drugs at an annual music festival. Drug and Alcohol Review, 32(6), 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M. S. C., Hellard, M. E., Hocking, J. S., & Aitken, C. K. (2008). A cross-sectional survey of young people attending a music festival: Associations between drug use and musical preference. Drug and Alcohol Review, 27(4), 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maasz, G., Molnar, E., Mayer, M., Kuzma, M., Takács, P., Zrinyi, Z., Pirger, Z., & Kiss, T. (2021). Illicit drugs as a potential risk to the aquatic environment of a large freshwater lake after a major music festival. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 40(5), 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackuľak, T., Brandeburová, P., Grenčíková, A., Bodík, I., Staňová, A. V., Golovko, O., Koba, O., Mackuľaková, M., Špalková, V., Gál, M., & Grabic, R. (2019). Music festivals and drugs: Wastewater analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 659, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackuľak, T., Škubák, J., Grabic, R., Ryba, J., Birošová, L., Fedorova, G., Špalková, V., & Bodík, I. (2014). National study of illicit drug use in Slovakia based on wastewater analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 494–495, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadarajan, D., O’Brien, J., Cresswell, S., Kele, B., Mueller, J., & Bade, R. (2024). Application of design of experiment for quantification of 71 new psychoactive substances in influent wastewater. Analytica Chimica Acta, 1321, 343036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M. E., Bryant, S. M., & Aks, S. E. (2014). Emerging drugs of abuse. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, 32(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D. J., & Cragg, G. M. (2012). Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. Journal of Natural Products, 75(3), 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, J., Carpenter, D., Fisher, M., Goodson, S., Hannah, B., Kwiatkowski, R., Prutton, K., Reeves, D., & Wainwright, T. (2021). BPS code of human research ethics. British Psychological Society (BPS). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ort, C., Bijlsma, L., Castiglioni, S., Covaci, A., De Voogt, P., Emke, E., Hernández, F., Reid, M., Van Nuijs, A. L. N., Thomas, K. V., & Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. (2018). Wastewater analysis for community-wide drugs use assessment. In H. H. Maurer, & S. D. Brandt (Eds.), New psychoactive substances (Vol. 252, pp. 543–566). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ort, C., Van Nuijs, A. L. N., Berset, J., Bijlsma, L., Castiglioni, S., Covaci, A., De Voogt, P., Emke, E., Fatta-Kassinos, D., Griffiths, P., Hernández, F., González-Mariño, I., Grabic, R., Kasprzyk-Hordern, B., Mastroianni, N., Meierjohann, A., Nefau, T., Östman, M., Pico, Y., … Thomas, K. V. (2014). Spatial differences and temporal changes in illicit drug use in Europe quantified by wastewater analysis. Addiction, 109(8), 1338–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSF. (n.d.). Available online: https://osf.io/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Ovid. (n.d.). Ovid: Welcome to Ovid. Available online: https://ovidsp.ovid.com/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S., Khan, S., M, S., Hamid, P., Patel, S., Khan, S., M, S., & Hamid, P. (2020). The association between cannabis use and schizophrenia: Causative or curative? A systematic review. Cureus, 12(7), e9309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PRISM. (2020). PRISMA 2020 checklist. PRISMA statement. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-checklist (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- PubMed. (n.d.). PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Puljević, C., Tscharke, B., Wessel, E. L., Francis, C., Verhagen, R., O’Brien, J. W., Bade, R., Nadarajan, D., Measham, F., Stowe, M. J., Piatkowski, T., Ferris, J., Page, R., Hiley, S., Eassey, C., McKinnon, G., Sinclair, G., Blatchford, E., Engel, L., … Barratt, M. J. (2024). Characterising differences between self-reported and wastewater-identified drug use at two consecutive years of an Australian music festival. Science of the Total Environment, 921, 170934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, V., Martinotti, G., & Maina, G. (2024). Substance-induced psychosis: Diagnostic challenges and phenomenological insights. Psychiatry International, 5(4), 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepis, T. S., Klare, D. L., Ford, J. A., & McCabe, S. E. (2020). Prescription drug misuse: Taking a lifespan perspective. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 14, 1178221820909352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senta, I., Krizman-Matasic, I., Kostanjevecki, P., Gonzalez-Mariño, I., Rodil, R., Quintana, J. B., Mikac, I., Terzic, S., & Ahel, M. (2023). Assessing the impact of a major electronic music festival on the consumption patterns of illicit and licit psychoactive substances in a Mediterranean city using wastewater analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 892, 164547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloboda, Z. (2002). Drug abuse epidemiology: An overview. Bulletin on Narcotics. [Google Scholar]

- Sutlović, D., Kuret, S., & Definis, M. (2021). New psychoactive and classic substances in pooled urine samples collected at the Ultra Europe Festival in Split, Croatia. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, 72(3), 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner-Smith, E. E. (2006). Pharmacological content of tablets sold as “ecstasy”: Results from an online testing service. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 83(3), 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternes, T. A. (1998). Occurrence of drugs in German sewage treatment plants and rivers. Water Research, 32(11), 3245–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UKRI. (2014). MRC Principles and guidelines for good research practice. UKRI. Available online: https://www.ukri.org/publications/principles-and-guidelines-for-good-research-practice/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2025). Current good manufacturing practice (CGMP) regulations. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/pharmaceutical-quality-resources/current-good-manufacturing-practice-cgmp-regulations (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- VanGeest, J. B., Johnson, T. P., & Alemagno, S. A. (Eds.). (2017). Research methods in the study of substance abuse. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Havere, T., Vanderplasschen, W., Lammertyn, J., Broekaert, E., & Bellis, M. (2011). Drug use and nightlife: More than just dance music. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 6(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verovšek, T., Krizman-Matasic, I., Heath, D., & Heath, E. (2020). Site- and event-specific wastewater-based epidemiology: Current status and future perspectives. Trends in Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 28, e00105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H., Bryant, J., Holt, M., & Treloar, C. (2010). Normalisation of recreational drug use among young people: Evidence about accessibility, use and contact with other drug users. Health Sociology Review, 19(2), 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstock, A. R., Griffiths, P., & Stewart, D. (2001). Drugs and the dance music scene: A survey of current drug use patterns among a sample of dance music enthusiasts in the UK. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 64(1), 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, C. L., Ball, T., Kambour, K., Machado, L., Defrancesco, T., Hamilton, C., Hyatt, J., & Dauk, J. (2020). Music and substance use: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 19(2), 208–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccato, E., & Castiglioni, S. (2009). Illicit drugs in the environment. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 367(1904), 3965–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s), Year, Country | Festival and Sample Details | Sampling Method | Analytical Technique | Substances Detected | Main Findings | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Bade et al., 2024), Australia | One multi-day music festival in Australia (May 2022); samples collected from an on-site treatment facility | 24 h composite wastewater samples analysed using a targeted approach informed by in vitro metabolism assays | LC-MS/MS + LC-–HRMS supported by in vitro metabolism for confirmation of drug metabolites | α-D2PV (parent compound) and three metabolites (M1, M2: hydroxylated; M4: dehydrogenated) | First WBE application targeting α-D2PV; results demonstrate potential for integrating in vitro data to support NPS detection in wastewater | Qualitative detection only (no reference standards available); proposed method supports improved biomarker identification for future NPS monitoring |

| (Benaglia et al., 2020), Switzerland | Two consecutive editions (2014 and 2015) of a multi-day music festival in Switzerland, attended by ~50,000 people daily; samples were collected from the local sewage treatment plant, which received all wastewater from the festival and the city | 24 h composite wastewater samples collected during both festival and baseline periods | SPE-LC-MS/MS was used to quantify 14 target compounds; statistical modelling was applied to account for uncertainty | MDMA, cocaine, AMPH, MAMPH, BZE, THC-COOH, 6MAM; ketamine, mephedrone and methylone were detected but not quantified; LSD and BZP were not detected | MDMA and AMPH showed significantly higher per capita loads during the festival compared to baseline, suggesting increased consumption during the event; cocaine use remained stable; MAMPH increased slightly but remained low; findings were consistent across both years | Comparison with seizure data suggested that MDMA and AMPH were often purchased on-site, supporting the existence of a festival drug market; authors recommend targeted prevention measures such as drug checking |

| (Berset et al., 2010), Switzerland | Street Parade 2009 in Zurich (600,000 participants); samples collected from five major street parades in Switzerland (Bern, Basel, Geneva, Lucerne, Zurich) from July to October 2009; comparative study conducted with reference sample versus sample collected day after the street parade | 24 h flow rate-dependent composite wastewater samples; river water collected as grab samples (n = 22); lake water samples from Lake Thun, Lake Brienz, and Lake Biel at various depths | HPLC-MS/MS using large volume injection (100 μL) with minimal sample preparation; 12 drugs analysed | In influents and effluents: Cocaine, BZE, morphine, methadone and its main metabolite EDDP; followed by codeine and amphetamine; THC-COOH detected <LOQ; in rivers and lakes: BZE, methadone, EDDP most frequently detected | Major substances in influents: Cocaine, BZE, morphine (up to 2 μg/L), followed by codeine, methadone, EDDP (up to 600 ng/L), amphetamines and amphetamine-like stimulants (e.g., MDMA) (up to 100 ng/L); Cocaine, BZE, and amphetamine-like stimulants (e.g., MDMA) higher on day after event compared to reference sample | Street parades are associated with short-term concentration peaks |

| (Bijlsma et al., 2014), Spain | Large pop/rock music festival in Benicàssim, Spain (July 2008, ~40,000 attendees); samples collected daily from three STPs (Benicàssim, Castellón, Burriana) during three separate weeks: June (summer), July (festival), and January/April (non-festival) | Daily 24 h composite samples taken from influent and effluent wastewater; comparison made across seasonal and festival timepoints | SPE–UHPLC–MS/MS targeting 11 parent drugs and metabolites | Cocaine, BZE, MDMA, MDA, MDEA, amphetamine, methamphetamine, THC-COOH, BZE, cocaethylene; some seasonal or festival-specific variations | Significant increase in MDMA and MDA during the festival (MDMA >27 μg/L); cocaine and BZE prevalent across all sites; THC-COOH only detected in July | Results support MDMA being festival-associated |

| (Bijlsma et al., 2020), Multi-country (Europe) | Six music festivals in six European countries (UK, Belgium, Norway, Portugal, Serbia, Spain) were sampled between 2015 and 2018 using pooled urine (UK, BE, NO) and wastewater (PT, RS, ES) | Pooled urine from male urinals and 24 h composite wastewater samples at WWTPs; samples collected during peak festival hours or daily over event duration, as well as during a non-festival period | SPE + LC-MS/MS + LC-HRMS for targeted quantification of 197 NPSs, 6 illicit drugs and metabolites | Multiple illicit drugs and 21 NPSs identified; MDMA and cocaine (highest in UK and Belgium, Serbia and Spain), amphetamine and methamphetamine (Norway), THC-COOH (Portugal and Spain), ketamine and NPSs such as 4-FMC, 4-MEC, α-PVP, butylone, ethylone and MDPV (mainly in the UK) | Observed country-level preferences of illicit drugs; UK showed highest NPS diversity; ketamine concentrations increased in UK 2016 samples | First comprehensive comparative study across multiple European festivals; highlighted the demographic limitation of pooled urine sampling (male urinals); proposed combined use of wastewater and urine samples for improved representativeness |

| (Bodík et al., 2016), Slovakia | National study covering 15 Slovak cities (2013–2014); includes cities with music festivals such as Trenčín and Piešťany | 24 h composite influent samples collected using automated samplers across 15 WWTPs; sampling covered weekdays and weekends; multiple samples per day were analysed | In-line SPE–LC-HRMS (Orbitrap) | Methamphetamine, MDMA, BZE, THC-COOH; also screened for psychiatric drugs and 120+ pharmaceuticals, but only the ones with the highest concentrations were discussed (e.g., tramadol, venlafaxine) | Methamphetamine was most commonly detected nationwide; MDMA concentrations peaked during festivals; cannabis use highest in Bratislava (112 mg/day/1000 inh) and Petržalka (74 mg/day/1000 inh); BZE levels suggested low cocaine use compared to Western Europe | Festival peaks observed in Trenčín (MDMA 207 ng/L) and Piešťany (159 ng/L); supports EMCDDA and police trends |

| (Brandeburová et al., 2020), Slovakia | Three music festivals in Slovakia: Pohoda (multicultural), Grape (dance), Lodenica (folk); ~50,000 attendees; samples from 9 cities over two years (2017–2018); 10 WWTPs | 24 h composite influent samples collected every 15 min using automatic samplers; included samples before, during, and after festivals | SPE followed by LC-MS/MS for detection of 30 NPS (synthetic cathinones and phenethylamine) | EtS (for alcohol) and 5 NPSs including synthetic cathinones (mephedrone, methcathinone, buphedrone, pentedrone), and phenethylamines (25-iP-NBOMe) | Five NPS detected at low ng/L; mephedrone and methcathinone were most common | This was the first WBE study on NPS in Slovakia; confirmed higher NPS levels during festivals; mass loads support findings from other EU cities |

| (Brett et al., 2022), Australia | Six single-day music festivals in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, held between March 2019 and March 2020; all were predominantly electronic dance music (EDM) events; festival attendance ranged from 6200 to 14,975 | Wastewater sampled from portaloos and/or pooled tanks at end of event using pipette method | SPE followed by Ultra High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC); screened for 98 psychoactive substances or metabolites | High-frequency detections: MDMA, MDA, cocaine, amphetamine, ketamine, methylone, alprazolam, diazepam, etizolam, oxazepam, temazepam; also detected: methcathinone, mephedrone, ethylone, N-ethylpentylone, norfentanyl | All major substances detected at all festivals; detection frequency for cathinones (e.g., mephedrone, methylone) higher than expected (suggesting adulteration or substitution); NPS not self-reported by survey participants | Wastewater sampling feasible and complementary to other data sources; limitations include inconsistent sampling and lack of quantitative analysis |

| (Devault et al., 2020), France | World Music Day (June 21) in Bordeaux, monitored in 2017 and 2018; sampling from two WWTPs (~1 million inhabitants total) | 24 h flow-proportional composite influent samples collected using refrigerated autosamplers; sampling occurred daily for one week including the Music Day | SPE + LC-MS/MS | cocaine, BZE, MDMA, THC-COOH, cocaethylene | Illicit drug use (cocaine, MDMA, cannabis) increased from 2017 to 2018; however, no specific increase was observed on World Music Day | Authors suggest lack of peer audience and public nature of event as reasons for no Music Day effect; first report of stable drug use during such a large event. |

| (Geuens et al., 2022), Belgium | Major international music festival in Flanders, Belgium, summer 2019 (~70,000 attendees per day); pooled urine samples collected at four different festival locations over three consecutive days (Friday–Sunday) | Pooled urine collected at men’s urinals via pumps; samples taken at 2 p.m., 5 p.m., 8 p.m., and 11 p.m. | GC-FID and LC-MS/MS (QTRAP) for 13 classical drugs; QTOF-MS for broad screening of NPS and adulterants | MDMA, MDA, ketamine, amphetamines, THC-COOH, cocaine (qualitative only), cocaethylene; NPS detected; also detected: flecainide, amlodipine, and other medications | MDMA and ketamine in all samples, often at high levels; cocaine confirmed in all samples qualitatively, but not quantitatively; two NPS (FMA and MMC) identified; widespread presence of prescription/OTC medications | Urine-based pooled sampling feasible for festival drug surveillance; limitations include male-only sampling and potential for environmental contamination |

| (Gjerde et al., 2019), Norway | Three music festivals in Norway (EDM and pop/rock); two urban and one rural setting; ~651 self-report participants + pooled urine sampling from portable urinals | Self-reported surveys, oral fluid samples, and pooled urine from urinals; combined individual and anonymous data collection | Oral fluid: UHPLC-MS/MS; pooled urine: LC-MS/MS and LC-HRMS; in-house database used for NPS screening | THC-COOH, MDMA, cocaine, amphetamines, ketamine, and multiple NPS | Self-reports underestimated actual drug use; MDMA most frequently detected in both biological samples; NPS use confirmed by urine but not always self-reported; poly-drug use observed; cocaine and ketamine also common | Triangulation of biological and self-report data revealed discrepancies in reported vs. actual drug use |

| (Gomes et al., 2025), Brazil | Carnatal Festival, held in December 2022 Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil; samples collected across four days of the festival and the days before and after it | 24 h composite influent wastewater samples collected from WWLS | SPE + UHPLC-MS/MS | BZE, cocaine, cocaethylene, MDMA detected throughout all days; BZE was most abundant | Cocaine use was substantially higher than MDMA across all days | First study to use WBE for a major music event in Brazil |

| (Hoegberg et al., 2018), Denmark | Roskilde Festival (Denmark); 44 samples collected over multiple days from urinals | Pooled urine collected from urinals in 3 areas; sampling conducted at different times of day and stored on ice; total of 44 urine samples collected | UPLC-HR-TOF-MS and immunoassays | 77 drugs and metabolites identified: MDMA, MDA, cocaine, amphetamine, THC-COOH, ketamine (detected in 17 samples using UPLC-HR-TOF-MS but NOT detected in any urine drug-screening immunoassays); no NPS confirmed by mass spectrometry | Classical recreational drugs detected in high frequency, especially MDMA and cocaine; no NPS detected despite expectations; significant discrepancy between immunoassay and UPLC-HR-TOF-MS results | First festival study in Denmark using pooled urine analysis; demonstrated limitations of immunoassays for pooled urine screening; highlighted advantages of HRMS |

| (Jiang et al., 2015), Taiwan | Spring Scream festival, pop music event in Taiwan(~600,000 attendees); samples collected before, during, and after the 2011 festival week | Grab samples of wastewater influents and effluents collected daily for one week from 2 WWTPs; river water also sampled across 28 locations during festival and non-festival times | SPE + LC-MS/MS; separate methods for pharmaceuticals and illicit drugs | Detected up to 30 emerging contaminants including ketamine, MDMA, caffeine, acetaminophen, diclofenac, gemfibrozil, codeine | Substantial increases in illicit drug and pharmaceutical concentrations in wastewater during the festival, especially ketamine (138,000 ng/L) and MDMA (1267 ng/L) | River sample approach complemented wastewater data |

| (Kinyua et al., 2016), UK and Belgium | Study analysed pooled urine from chemical toilets collected at festivals in the UK and Belgium, as well as a UK city centre; sampling locations were selected as drug use ‘hotspots’ | 23 grab samples taken from chemical toilets (male urinals) at UK and Belgian festivals and UK city centre locations | LC–QTOF-MS; screening performed using a comprehensive in-house HRMS spectral library with >600 entries | In total, 53 substances were detected in UK samples and 28 in Belgian samples, including NPS (e.g., methylone, mephedrone, ketamine, 4-FA, α-PVP), and classical drugs (e.g., MDMA, cocaine, amphetamine, MDA, THC-COOH) | Higher diversity of NPS in UK samples; results reflect geographical differences in recreational drug use patterns | First comparative study using pooled urine from festivals and city centres to monitor NPS prevalence; results support pooled urine as a viable tool for NPS monitoring at public events |

| (Lai et al., 2013), Australia | Australian multiday summer festival in two consecutive years 2010 and 2011 (~16,700 daily attendees in 2010 and ~14,700 in 2011) | 24 h composite wastewater samples collected from on-site WWTP inlet | LC-MS/MS; some targets required SPE (e.g., THC-COOH), others analysed directly after filtration | THC-COOH, MDMA, methamphetamine, cocaine, amphetamine, BZE; also detected: benzyl piperazine, mephedrone, methylone (emerging psychostimulants) | Drug use increased over festival days, peaking on final day; MDMA use significantly elevated compared to nearby urban area; methamphetamine and BZP declined from 2010 to 2011 | One of the first studies to measure NPS via wastewater at festivals |

| (Maasz et al., 2021), Hungary | Large annual music festival held on Lake Balaton shore, Hungary (attendance: 154,000–172,000); water samples collected from multiple sites before, during, and after the festival | Grab sampling at nearshore and remote sites; samples collected April, June, July (1 day after event), August, and November across 3 years (2017, 2018, 2019) | SPE + SFC-MS/MS | Cocaine, BZE, MDMA, ketamine, methamphetamine, amphetamine, MDA, MDAI; cocaine, BZE, MDMA, and ketamine consistently detected | Illicit drug concentrations peaked 1 day post-festival and declined within 1 month; cocaine and MDMA were consistently observed across years in the highest concentrations | Weather (wind/rain) affected detection patterns; findings suggest festivals may transiently contaminate lake ecosystems with biologically active substances |

| (Mackuľak et al., 2014), Slovakia | Two Slovak music festivals in 2013: Pohoda (multicultural, Trenčín, ~30,000 attendees), Lodenica (folk/country, Piešťany, ~10,000 attendees); samples collected during and one week after each festival | 24 h composite sampling at 8 WWTPs using automatic samplers; 15 min intervals; control samples taken one week later | SPE + LC-MS/MS | Methamphetamine, amphetamine, MDMA, cocaine, BZE, THC-COOH. Significant festival-associated increases: MDMA at Pohoda (up to 29 mg/day/1000 inh.); cocaine at both festivals; no THC-COOH increase | High methamphetamine use across Slovakia; cocaine and MDMA use spiked during festivals, particularly in Trenčín; drug load patterns varied by drug type and event demographics | MDMA consumption varied with music style; cannabis use widespread but not festival-associated |

| (Mackuľak et al., 2019), Czech Republic and Slovakia | Seven large-scale music festivals in Slovakia and Czech Republic during summer 2017 (metal, rock, pop, electronic, country, folk, ethnic, dance, multi-genre); total estimated attendance: >130,000 | 24 h composite influent wastewater samples collected from six WWTPs serving festival locations; parallel sampling at a control site with no festival activity | In-line SPE–LC-HRMS (Orbitrap) | MDMA, amphetamine, methamphetamine, cocaine, THC-COOH and 5 psychoactive pharmaceuticals (tramadol, citalopram, venlafaxine, codeine, oxazepam); significant increases in MDMA, amphetamine, and cocaine loads during festivals | Drug residues significantly elevated during festivals compared to background values and control city; MDMA showed the highest proportional increase; substance patterns varied by festival type and attendee demographics | First comparative WBE study across multiple Central European festivals; findings highlight music genre-specific drug consumption trends |

| (Nadarajan et al., 2024), Australia | Sampling conducted at a multi-day music festival in Queensland, Australia; wastewater collected daily from 25 December 2022 to 1 January 2023 | Time-based composite influent wastewater samples collected every 15 min over 24 h periods using autosampler | SPE + LC-MS/MS; suspect screening for 71 substances, including NPSs | Multiple NPS identified across samples (from the total of 71 screened compounds, 7 were detected) | Seven substances were positively identified in festival wastewater | Demonstrated feasibility of NPS surveillance using WBE at temporary events; highlights challenges of interpreting unlabelled compounds using suspect screening |

| (Puljević et al., 2024), Australia | Five-day music festival in Queensland, Australia, studied in both 2021 and 2022; sampling covered 5 days: 2 pre-festival, 3 during-festival | Wastewater influent samples collected daily during the five-day festivals in 2021 and 2022 (samples collected using a portable refrigerated autosampler) | SPE + LC-MS/MS | MDMA, THC-COOH, cocaine, ketamine, LSD, MDA Other substances found, but not reported in surveys: MDEA, mephedrone, methylone, 3-MMC, α -D2PV, etizolam, eutylone, and N,N-dimethylpentylone | Triangulation revealed under-reporting in survey data; numerous chemicals identified in wastewater but not disclosed in surveys presumably indicate substitutions or adulterants | Emphasised strength of mixed-methods for estimating population-level drug use |

| (Senta et al., 2023), Croatia | Electronic music festival in Split, Croatia; wastewater samples collected during three periods: festival week (13–19 July), peak-tourist reference week (24–30 August), and off-tourist reference week (9–15 November) | 24 h time-proportional composite samples collected every 15 min from two main wastewater collectors (Stupe and Katalinica Brig) | SPE + LC-MS/MS | MDMA, cocaine, amphetamine, cannabis, heroin, morphine, codeine, tramadol, NPSs, methamphetamine | MDMA loads increased 30-fold during the festival compared to off-season and 15-fold versus peak-tourist week; smaller increases observed for AMP and cocaine (1.7-fold); NPS and MAMP detected at low levels | Highlights clear distinctions between festival and non-festival periods |

| (Sutlović et al., 2021), Croatia | Ultra Europe electronic music festival in Split, Croatia; samples collected during 2016–2018 festivals (30 pooled urine samples were collected from portable chemical toilets); over 150,000 attendees from more than 150 countries | Syringe collection from toilets; toilets were sampled across different days and locations each year | SPE + GC/MS | 46 substances detected in total: 26 classic drugs (e.g., MDMA, cocaine, amphetamine, ketamine) and 20 NPS (e.g., methcathinone, methylone, phenethylamines, cathinones, tryptamines) | Highest number of substances found on the first day of the festival; classic drug use remained stable across years, while NPS prevalence declined sharply by 2018; methcathinone was detected for the first time in 2018 | Demonstrates the effectiveness of pooled urine sampling at festivals; 2018 results align with reported EU-wide decline in NPS availability (in line with EMCDDA findings) |

| Analytical Technique | Explanation | Application in This Review |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | A highly sensitive analytical method that separates substances in a liquid sample and identifies them based on their mass-to-charge ratio. It is widely used for detecting and quantifying trace levels of drugs in complex biological matrices such as wastewater. | Used in the majority of studies (16 out of 23) to detect commonly used substances such as MDMA, cocaine, and amphetamines at very low concentrations. Primary quantitative method across studies including Benaglia et al. (2020), Berset et al. (2010), Bijlsma et al. (2014), Brandeburová et al. (2020), and others. |

| LC-HRMS (Liquid Chromatography–High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry) | An advanced analytical technique that provides highly accurate mass measurements and superior compound identification capabilities compared to conventional MS. Essential for NPS detection and confirmation. | Used in 5 out of 23 studies for NPS identification including Bade et al. (2024), Bijlsma et al. (2020), Bodík et al. (2016), Gjerde et al. (2019), and Mackuľak et al. (2019). |

| SPE (Solid-Phase Extraction) | A preparatory technique used to isolate and concentrate analytes of interest from a sample by passing it through a solid absorbent material. This process reduces interference and improves reliability. | Standard sample preparation in 17 out of 23 studies to purify wastewater before further analysis using LC-MS/MS or related methods. Essential for achieving detection limits required for trace-level festival drug monitoring. |

| GC-MS (Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry) | An analytical technique that vaporises chemical substances and separates them by their physical and chemical properties before identifying them through mass spectrometry. | Applied in 3 studies (Sutlović et al., 2021; Geuens et al., 2022; Maasz et al., 2021 using SFC-MS/MS variant) to identify classic drugs of abuse, particularly those that are volatile or stable at high temperatures. Less common but effective for specific compound classes. |

| QTOF-MS (Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry) | A hybrid mass spectrometry technique combining quadrupole ion selection with time-of-flight mass analysis, providing high mass accuracy and the ability to perform both targeted and untargeted analysis. | Used in 2 studies (Geuens et al., 2022; Kinyua et al., 2016) for comprehensive screening of classical drugs and NPS. |

| UPLC-HR-TOF-MS (Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography High-Resolution Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectrometry) | The most advanced form of mass spectrometry that allows for comprehensive screening of both known and emerging substances. | Specialised technique employed in Hoegberg et al. (2018) focusing on detection of emerging drug trends and novel substances. Demonstrated clear advantages over traditional immunoassays for pooled urine analysis, but showed limitations for NPS detection despite expectations. |

| Country | Preferred Drugs | Studies Referenced | Key Regional Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Traditional Drugs: MDMA (festival-dominant), MDA, cannabis, methamphetamine, cocaine, amphetamine, ketamine NPS: α-D2PV, N-ethylpentylone, mephedrone, methylone Pattern: MDMA consumption “substantially higher” at festivals vs. residential areas | Bade et al. (2024); Brett et al. (2022); Lai et al. (2013); Nadarajan et al. (2024); Puljević et al. (2024) | Festival vs. Residential Differences: Cannabis > MDMA > Methamphetamine > Cocaine (festival) vs. Cannabis > Methamphetamine > MDMA > Cocaine (urban). First country to apply DOE optimisation for 71 NPS detection. |

| Belgium | Traditional Drugs: MDMA (highest concentrations), MDA, cocaine, amphetamine, cannabis, ketamine NPS: 4-FMC, 4-MEC, α-PVP, 2C-B, 4-FA | Bijlsma et al. (2020); Geuens et al. (2022); Kinyua et al. (2016) | Lower NPS diversity compared to UK. Critical safety finding: Dangerous cardiac medications used as cocaine adulterants (flecainide and amloidipine) MDMA consistently high relative to other traditional drugs. |

| Brazil | Traditional Drugs: Cocaine (substantially higher than MDMA), MDMA, BZE, cocaethylene Pattern: Festival-associated increases | Gomes et al. (2025) | Cocaine-dominant pattern (unusual compared to European MDMA dominance). Wastewater data revealed higher usage levels than national averages. |

| Croatia | Traditional Drugs: MDMA, cocaine, amphetamine, cannabis NPS: phenethylamines and cathinones (primarily) | Sutlović et al. (2021); Senta et al. (2023) | Sutlović et al. (2021): 46 total substances (26 classic + 20 NPS) from pooled urine 2016–2018. Senta et al. (2023): Comprehensive wastewater analysis with 30-fold MDMA increase, stable cannabis/heroin/opioids/nicotine. |

| Czech Republic | Traditional Drugs: Methamphetamine-dominant (historical legacy), cannabis, MDMA, cocaine, amphetamine Psychoactive pharmaceuticals: tramadol, citalopram, venlafaxine, codeine, oxazepam | Mackuľak et al. (2019) | Key pattern: Shared post-Communist methamphetamine dominance with Slovakia Festival findings: Similar drug consumption patterns to Slovakia during music festivals |

| Denmark | Traditional Drugs: MDMA, MDA, cocaine, amphetamine, cannabis, ketamine NPS: Lower than expected based on seizure data | Hoegberg et al. (2018) | Ketamine detected in 17 samples by HRMS but zero detection by immunoassays (demonstrated analytical method superiority). |

| France | Traditional Drugs: Cocaine, BZE, MDMA, cannabis, cocaethylene | Devault et al. (2020) | No specific festival effect observed (attributed to event’s public nature and diverse audience). |

| Hungary | Traditional Drugs: MDMA, cocaine, BZE, ketamine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, MDA, MDAI | Maasz et al. (2021) | Environmental contamination of lake ecosystem with psychoactive substances. Weather effects on detection patterns observed. |

| Norway | Traditional Drugs: MDMA (lower than cocaine), cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine/methamphetamine sufficient for quantification (unique pattern), NPS: Various substances detected in pooled urine | Bijlsma et al. (2020); Gjerde et al. (2019) | Different amphetamine-type pattern: higher amphetamine/methamphetamine usage in Norway (high enough to quantify accurately), while other countries (UK, Belgium) had levels too low for reliable quantification (Bijlsma et al., 2020). Contradictory findings: “neither amphetamine, methamphetamine, ketamine, cathinones, phenethylamines nor other NPS were used by a significant proportion of the participants” (Gjerde et al., 2019) |

| Portugal | Traditional Drugs: Cannabis (10x increase during festival), MDMA, cocaine, amphetamine NPS: 3,4-DMMC, α-methyltryptamine, methcathinone, mephedrone, buphedrone, ketamine | Bijlsma et al. (2020) | Festival-specific NPS use: Zero NPS in non-festival samples. Cannabis showed most dramatic increase (10-fold) during festival period. |

| Serbia | Traditional Drugs: MDMA clearly most prevalent during festivals, amphetamine, cocaine, cannabis Pattern: MDMA-dominant festival culture | Bijlsma et al. (2020) | MDMA-centric festival culture with clear dominance over other substances during electronic music events. 30-fold MDMA increase during festivals. |

| Slovakia | Traditional Drugs: Methamphetamine-dominant (historical legacy), cannabis, MDMA, cocaine, BZE NPS: cathinones and phenethylamines (primarily) Psychoactive pharmaceuticals: tramadol, citalopram, venlafaxine, codeine, oxazepam Geographic Pattern: Highest cocaine in Bratislava, highest meth in rural areas | Bodík et al. (2016); Brandeburová et al. (2020); Mackuľak et al. (2014); Mackuľak et al. (2019) | Post-Communist legacy: “EMCDDA counts Slovakia and Czech Republic among countries with dominant methamphetamine consumption” (Mackuľak et al., 2019) due to historical availability. Festival variety: Different substances for different music genres. |

| Spain | Traditional Drugs: Cocaine, MDMA, amphetamine, cannabis, BZE, MDA Temporal: Festival-associated increases | Bijlsma et al. (2014) Bijlsma et al. (2020) | Significant MDMA increases during festival periods. Wastewater treatment efficiency challenged during peak use. |

| Switzerland | Traditional Drugs: MDMA, amphetamine, methamphetamine, cocaine, cannabis, ketamine, BE, methadone, codeine NPS: Mephedrone and methylone (detected, but not quantified) | Benaglia et al. (2020) Berset et al. (2010) | Festival monitoring showed dramatic increases. Per capita increases: MDMA and cocaine increased substantially after events |

| Taiwan | Traditional Drugs: Mainly ketamine and MDMA Pattern: Detected 30 emerging substances with concentrations peaking during festival | Jiang et al. (2015) | Environmental focus: Spring Scream Festival monitoring of 30 sampling sites (28 river samples + 2 WWTPs). Pollution control perspective rather than epidemiological focus. |

| UK | Traditional Drugs: MDMA, cocaine, amphetamine, cannabis, ketamine NPS: Highest NPS diversity globally (53 substances detected) Temporal: More NPS in 2015 vs. 2016; ketamine concentrations increased 2016 | Bijlsma et al. (2020); Kinyua et al. (2016) | Global NPS leader: Highest diversity of novel substances. Geographic advantage: Comprehensive monitoring of both festivals and urban “drug hotspots”. |

| Theme | Main Findings |

|---|---|

| Sampling methodologies and analytical approaches | Two primary approaches: wastewater sampling and pooled urine sampling with LC-MS/MS and HRMS analytical methods Pooled urine sampling offers higher analyte concentrations but limited demographic representation |

| Substance detection patters | MDMA dominance across diverse geographical contexts and festival types Profound regional variations Music genre influences Substantially higher consumption during festival periods compared to baseline |

| Public health and harm reduction applications | Population-level anonymous monitoring enables objective evidence-based intervention design Early warning system potential for NPS and dangerous adulterants Temporal limitations: Lag between sample collection and result availability limits real-time harm reduction responses |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cainamisir, R.; Zeng, X.; Himmerich, S.B.; Himmerich, H. Wastewater Analyses for Psychoactive Substances at Music Festivals: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121672

Cainamisir R, Zeng X, Himmerich SB, Himmerich H. Wastewater Analyses for Psychoactive Substances at Music Festivals: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121672

Chicago/Turabian StyleCainamisir, Ringala, Xiao Zeng, Samuel B. Himmerich, and Hubertus Himmerich. 2025. "Wastewater Analyses for Psychoactive Substances at Music Festivals: A Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121672

APA StyleCainamisir, R., Zeng, X., Himmerich, S. B., & Himmerich, H. (2025). Wastewater Analyses for Psychoactive Substances at Music Festivals: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1672. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121672