Interventions to Reduce Implicit Bias in High-Stakes Professional Judgements: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Implicit Bias Within the Criminal Justice System

1.2. Limitations of Current Intervention Approaches

1.3. The Present Review

2. Method

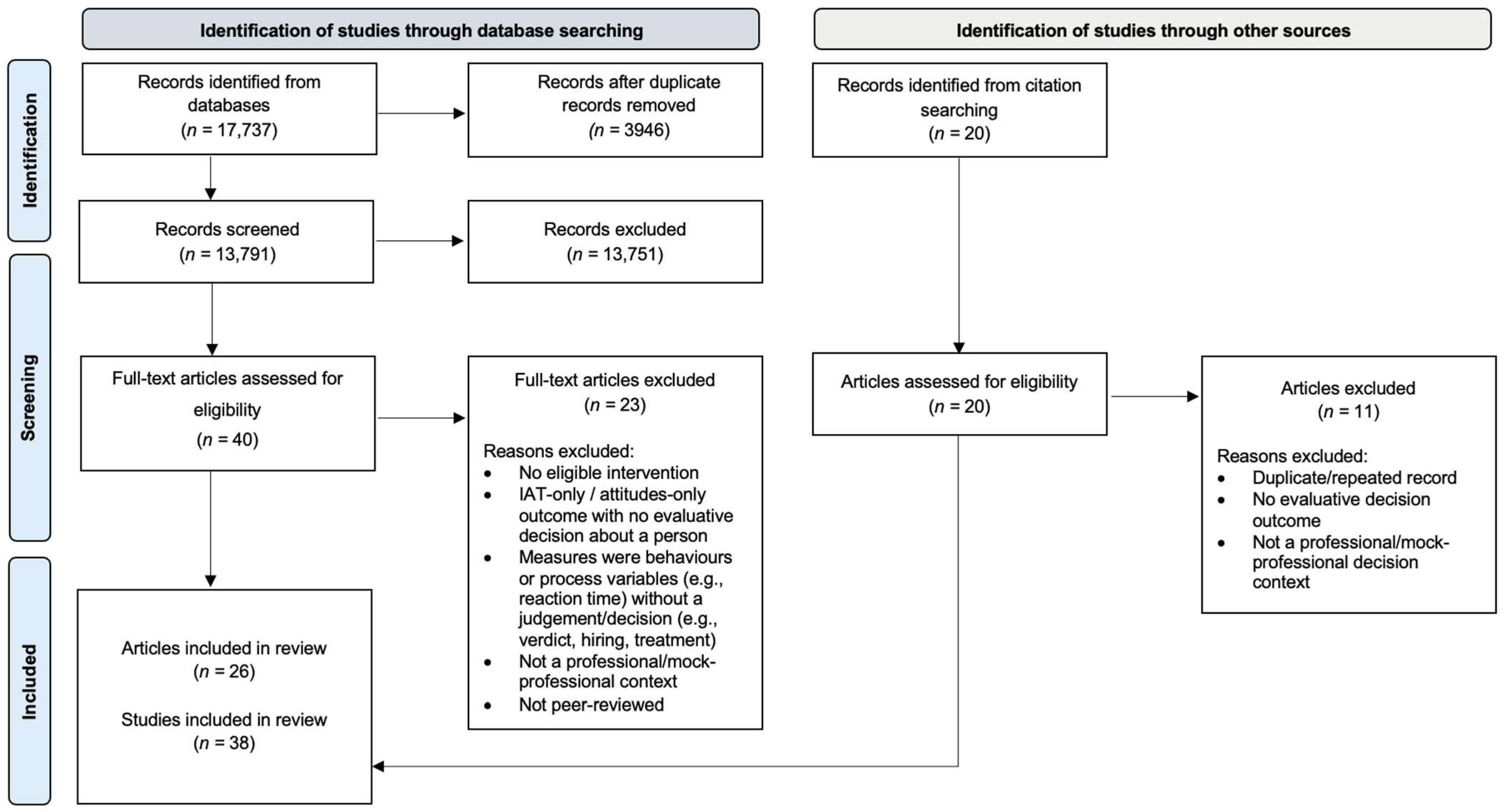

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Screening Process: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- (1)

- Focus on implicit bias: The study targeted bias in social evaluations related to social characteristics (e.g., race, gender, age). Bias was considered ‘implicit’ if it was described as automatic, unintentional, or unconscious, including related constructs using terms such as ‘automatic stereotyping’ or ‘unconscious associations’. Implicit bias was operationalised as a socially focused subtype of cognitive bias (i.e., a tendency for evaluative judgements to be influenced by automatic, unintentional processing of social characteristics). Accordingly, studies centred on non-social cognitive heuristics (e.g., anchoring, confirmation) or on explicit cultural attitudes/beliefs not characterised as automatic processes were ineligible and were excluded. Eligibility was therefore evidenced either by the authors’ framing of bias as automatic/unconscious social processing or by an empirical design that operationalised bias as a change in decisions produced by a social characteristic in the absence of task relevance or explicit intent (e.g., an evaluative decision task that manipulated a social characteristic while non-task-relevant to assess its effect on decisions).

- (2)

- Tested an intervention: The study examined an intentional strategy aimed at reducing or mitigating implicit bias in decision-making. Studies that reported incidental bias reduction without presenting it as a deliberate intervention were excluded.

- (3)

- Decision-making outcome: Outcomes had to reflect a meaningful judgement with real or simulated consequences about another person, such as sentencing, hiring, grading, performance evaluation, or treatment recommendation. Studies focused on attitudes, preferences, or affective ratings without an evaluative consequence were excluded.

- (4)

- Professional or mock-professional context: This included both real professionals acting in their formal roles (e.g., doctors, teachers, police officers) and lay participants who were explicitly instructed to take on a professional role (e.g., mock jurors, hiring decision-makers). Studies where outcomes could not be linked to an individual decision-maker were excluded.

2.3. Screening Process: Title, Abstract, and Full Text Review

2.4. Data Extraction

- (1)

- Study details: Captured core methodological and contextual information (e.g., year, country, professional field, study design, participant role, paradigm). Three ecological indicators (sample realism, task realism, and context realism) were also coded to assess the ecological validity of each study and the extent to which findings might generalise to applied professional settings.

- (2)

- Intervention characteristics: Documented each intervention’s design, delivery, mechanism of action, and timing. Interventions were classified both by level of operation (individual, systemic, or mixed) and by mechanism (e.g., altering information available at judgement, adding structure to reduce discretion, prompting self-regulation, reframing assumptions, or targeting automatic associations). These classifications facilitated structured comparison of strategies and their potential transferability.

- (3)

- Outcomes and findings: Extracted evidence on whether interventions reduced bias in consequential decisions (e.g., sentencing, hiring, grading, treatment). Effectiveness was judged against baseline bias and assessed for statistical significance, consistency, and durability. Secondary outcomes (e.g., implicit bias measures, participant feedback) were also recorded to provide contextual insight into mechanisms and broader impact.

- (4)

- Delivery practicality and implementation feasibility: Recorded information on format, materials, time demands, training needs, and scalability. Interventions were appraised for practicality (resource and process requirements) and feasibility (likelihood of adoption, fidelity, and sustainability under real-world constraints). Ratings of high, moderate, or low were applied across key aspects such as cost, facilitation needs, duration, and scalability.

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Study Characteristics

3.2. Overview of Intervention Effectiveness

3.3. Systemic-Level Interventions

3.3.1. Altering Information Available at Judgement

3.3.2. Adding Structure That Limits Discretion

3.4. Individual-Level Interventions

3.4.1. Prompting Self-Regulation at the Point of Decision

3.4.2. Reframing Assumptions

3.4.3. Targeting Automatic Associations

3.5. Mixed-Level Interventions

3.6. Practicality of Interventions

3.7. Transferability of Interventions

3.8. Critical Appraisal

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Full PsycInfo Search String

Appendix B

Data Extraction Framework and Coding Domains

Appendix C

QuADS Scoring Sheet

| Criterion | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1. Theoretical or conceptual underpinning to the research | No mention at all. | General reference to broad theories or concepts that frame the study. e.g., key concepts were identified in the introduction section. | Identification of specific theories or concepts that frame the study and how these informed the work undertaken. e.g., key concepts were identified in the introduction section and applied to the study. | Explicit discussion of the theories or concepts that inform the study, with application of the theory or concept evident through the design, materials and outcomes explored. e.g., key concepts were identified in the introduction section and the application apparent in each element of the study design. |

| 2. Statement of research aim/s | No mention at all. | Reference to what the study sought to achieve embedded within the report but no explicit aims statement. | Aims statement made but may only appear in the abstract or be lacking detail. | Explicit and detailed statement of aim/s in the main body of report. |

| 3. Clear description of research setting and target population | No mention at all. | General description of research area but not of the specific research environment e.g., ‘in primary care.’ | Description of research setting is made but is lacking detail e.g., ‘in primary care practices in region [x]’. | Specific description of the research setting and target population of study e.g., ‘nurses and doctors from GP practices in [x] part of [x] city in [x] country.’ |

| 4. The study design is appropriate to address the stated research aim/s | No research aim/s stated or the design is entirely unsuitable e.g., a Y/N item survey for a study seeking to undertake exploratory work of lived experiences. | The study design can only address some aspects of the stated research aim/s e.g., use of focus groups to capture data regarding the frequency and experience of a disease. | The study design can address the stated research aim/s but there is a more suitable alternative that could have been used or used in addition e.g., addition of a qualitative or quantitative component could strengthen the design. | The study design selected appears to be the most suitable approach to attempt to answer the stated research aim/s. |

| 5. Appropriate sampling to address the research aim/s | No mention of the sampling approach. | Evidence of consideration of the sample required e.g., the sample characteristics are described and appear appropriate to address the research aim/s. | Evidence of consideration of sample required to address the aim. e.g., the sample characteristics are described with reference to the aim/s. | Detailed evidence of consideration of the sample required to address the research aim/s. e.g., sample size calculation or discussion of an iterative sampling process with reference to the research aims or the case selected for study. |

| 6. Rationale for choice of data collection tool/s | No mention of rationale for data collection tool used. | Very limited explanation for choice of data collection tool/s. e.g., based on availability of tool. | Basic explanation of rationale for choice of data collection tool/s. e.g., based on use in a prior similar study. | Detailed explanation of rationale for choice of data collection tool/s. e.g., relevance to the study aim/s, co-designed with the target population or assessments of tool quality. |

| 7. The format and content of data collection tool is appropriate to address the stated research aim/s | No research aim/s stated and/or data collection tool not detailed. | Structure and/or content of tool/s suitable to address some aspects of the research aim/s or to address the aim/s superficially e.g., single item response that is very general or an open-response item to capture content which requires probing. | Structure and/or content of tool/s allow for data to be gathered broadly addressing the stated aim/s but could benefit from refinement. e.g., the framing of survey or interview questions are too broad or focused to one element of the research aim/s. | Structure and content of tool/s allow for detailed data to be gathered around all relevant issues required to address the stated research aim/s. |

| 8. Description of data collection procedure | No mention of the data collection procedure. | Basic and brief outline of data collection procedure e.g., ‘using a questionnaire distributed to staff’. | States each stage of data collection procedure but with limited detail or states some stages in detail but omits others e.g., the recruitment process is mentioned but lacks important details. | Detailed description of each stage of the data collection procedure, including when, where and how data was gathered, such that the procedure could be replicated. |

| 9. Recruitment data provided | No mention of recruitment data. | Minimal and basic recruitment data e.g., number of people invited who agreed to take part. | Some recruitment data but not a complete account e.g., number of people who were invited and agreed. | Complete data allowing for full picture of recruitment outcomes e.g., number of people approached, recruited, and who completed with attrition data explained where relevant. |

| 10. Justification for analytic method selected | No mention of the rationale for the analytic method chosen. | Very limited justification for choice of analytic method selected. e.g., previous use by the research team. | Basic justification for choice of analytic method selected e.g., method used in prior similar research. | Detailed justification for choice of analytic method selected e.g., relevance to the study aim/s or comment around of the strengths of the method selected. |

| 11. The method of analysis was appropriate to answer the research aim/s | No mention at all. | Method of analysis can only address the research aim/s basically or broadly. | Method of analysis can address the research aim/s, but there is a more suitable alternative that could have been used or used in addition to offer a stronger analysis. | Method of analysis selected is the most suitable approach to attempt answer the research aim/s in detail e.g., for qualitative interpretative phenomenological analysis might be considered preferable for experiences vs. content analysis to elicit frequency of occurrence of events. |

| 12. Evidence that the research stakeholders have been considered in the research design or conduct. | No mention at all. | Consideration of some of the research stakeholders e.g., use of pilot study with target sample but no stakeholder involvement in planning stages of study design. | Evidence of stakeholder input informing the research. e.g., use of a pilot study with feedback influencing the study design/conduct or reference to a project reference group established to guide the research. | Substantial consultation with stakeholders identifiable in planning of study design and in preliminary work e.g., consultation in the conceptualisation of the research, a project advisory group or evidence of stakeholder input informing the work. |

| 13. Strengths and limitations critically discussed | No mention at all. | Very limited mention of strengths and limitations, with omissions of many key issues. e.g., one or two strengths/limitations mentioned with limited detail. | Discussion of some of the key strengths and weaknesses of the study, but not complete. e.g., several strengths/limitations explored but with notable omissions or lack of depth of explanation. | Thorough discussion of strengths and limitations of all aspects of study including design, methods, data collection tools, sample & analytic approach. |

References

- * Anderson, A. J., Ahmad, A. S., King, E. B., Lindsey, A. P., Feyre, R. P., Ragone, S., & Kim, S. (2015). The effectiveness of three strategies to reduce the influence of bias in evaluations of female leaders. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45(9), 522–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axt, J., Posada, V. P., Roy, E., & To, J. (2025). Revisiting the policy implications of implicit social cognition. Social Issues and Policy Review, 19(1), e70003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Bragger, J. D., Kutcher, E., Morgan, J., & Firth, P. (2002). The effects of the structured interview on reducing biases against pregnant job applicants. Sex Roles, 46(7), 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Brauer, M., & Er-rafiy, A. (2011). Increasing perceived variability reduces prejudice and discrimination. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(5), 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buongiorno, L., Mele, F., Petroni, G., Margari, A., Carabellese, F., Catanesi, R., & Mandarelli, G. (2025). Cognitive biases in forensic psychiatry: A scoping review. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 101, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttrick, N., Axt, J., Ebersole, C. R., & Huband, J. (2020). Re-assessing the incremental predictive validity of Implicit Association Tests. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 88, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curley, L. J., Munro, J., & Dror, I. E. (2022). Cognitive and human factors in legal layperson decision making: Sources of bias in juror decision making. Medicine, Science and the Law, 62(3), 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curley, L. J., Munro, J., Lages, M., MacLean, R., & Murray, J. (2020). Assessing cognitive bias in forensic decisions: A review and outlook. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 65(2), 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curley, L. J., & Neuhaus, T. (2024). Are legal experts better decision makers than jurors? A psychological evaluation of the role of juries in the 21st century. Journal of Criminal Psychology, 14(4), 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Dahlen, B., McGraw, R., & Vora, S. (2024). Evaluation of simulation-based intervention for implicit bias mitigation: A response to systemic racism. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 95, 101596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, J. (2019). Implicit bias is behavior: A functional-cognitive perspective on implicit bias. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(5), 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Derous, E., Nguyen, H.-H. D., & Ryan, A. M. (2021). Reducing ethnic discrimination in resume-screening: A test of two training interventions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(2), 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbie, W., Goldin, J., & Yang, C. S. (2018). The effects of pre-trial detention on conviction, future crime, and employment: Evidence from randomly assigned judges. American Economic Review, 108(2), 201–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Döbrich, C., Wollersheim, J., Welpe, I. M., & Spörrle, M. (2014). Debiasing age discrimination in HR decisions. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 14(4), 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, I. E. (2025). Biased and biasing: The hidden bias cascade and bias snowball effects. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dror, I. E., Melinek, J., Arden, J. L., Kukucka, J., Hawkins, S., Carter, J., & Atherton, D. S. (2021). Cognitive bias in forensic pathology decisions. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 66(5), 1751–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edkins, V. A. (2011). Defense attorney plea recommendations and client race: Does zealous representation apply equally to all? Law and Human Behavior, 35(5), 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- * Feng, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, Z., & Savani, K. (2020). Let’s choose one of each: Using the partition dependence effect to increase diversity in organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 158, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, C., & Hurst, S. (2017). Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Medical Ethics, 18(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, C., Martin, A., Berner, D., & Hurst, S. (2019). Interventions designed to reduce implicit prejudices and implicit stereotypes in real world contexts: A systematic review. BMC Psychology, 7(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forscher, P. S., Lai, C. K., Axt, J. R., Ebersole, C. R., Herman, M., Devine, P. G., & Nosek, B. A. (2019). A meta-analysis of procedures to change implicit measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(3), 522–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Friedmann, E., & Efrat-Treister, D. (2023). Gender bias in stem hiring: Implicit in-group gender favoritism among men managers. Gender & Society, 37(1), 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawronski, B., Ledgerwood, A., & Eastwick, P. W. (2022). Implicit bias ≠ bias on implicit measures. Psychological Inquiry, 33(3), 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A. G., Dasgupta, N., Dovidio, J. F., Kang, J., Moss-Racusin, C. A., & Teachman, B. A. (2022). Implicit-bias remedies: Treating discriminatory bias as a public-health problem. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 23(1), 7–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- * Hamm, R. F., Srinivas, S. K., & Levine, L. D. (2020). A standardized labor induction protocol: Impact on racial disparities in obstetrical outcomes. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM, 2(3), 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R., Jones, B., Gardner, P., & Lawton, R. (2021). Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): An appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed- or multi-method studies. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Hirsh, A. T., Miller, M. M., Hollingshead, N. A., Anastas, T., Carnell, S. T., Lok, B. C., Chu, C., Zhang, Y., Robinson, M. E., Kroenke, K., & Ashburn-Nardo, L. (2019). A randomized controlled trial testing a virtual perspective-taking intervention to reduce race and socioeconomic status disparities in pain care. Pain, 160(10), 2229–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holroyd, J., & Sweetman, J. (2016). The heterogeneity of implicit bias. In M. Brownstein, & J. Saul (Eds.), Implicit bias and philosophy (Vol. 1, pp. 80–103). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, K., Uhrig, N., & Colahan, M. (2016). Associations between ethnic background and being sentenced to prison in the Crown Court in England and Wales in 2015. Ministry of Justice. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a814a3d40f0b62305b8e241/associations-between-ethnic-background-being-sentenced-to-prison-in-the-crown-court-in-england-and-wales-2015.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- * James, L., James, S., & Mitchell, R. J. (2023). Results from an effectiveness evaluation of anti-bias training on police behavior and public perceptions of discrimination. Policing: An International Journal, 46(5/6), 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Kawakami, K., Dovidio, J. F., & Van Kamp, S. (2005). Kicking the habit: Effects of nonstereotypic association training and correction processes on hiring decisions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(1), 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Kawakami, K., Dovidio, J. F., & Van Kamp, S. (2007). The impact of counterstereotypic training and related correction processes on the application of stereotypes. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 10(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Kleissner, V., & Jahn, G. (2021). Implicit and explicit age cues influence the evaluation of job applications. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51(2), 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovera, M. B. (2019). Racial disparities in the criminal justice system: Prevalence, causes, and a search for solutions. Journal of Social Issues, 75(4), 1139–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, B., Seitchik, A. E., Axt, J. R., Carroll, T. J., Karapetyan, A., Kaushik, N., Tomezsko, D., Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (2019). Relationship between the implicit association test and intergroup behavior: A meta-analysis. American Psychologist, 74(5), 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C. K., Skinner, A. L., Cooley, E., Murrar, S., Brauer, M., Devos, T., Calanchini, J., Xiao, Y. J., Pedram, C., Marshburn, C. K., Simon, S., Blanchar, J. C., Joy-Gaba, J. A., Conway, J., Redford, L., Klein, R. A., Roussos, G., Schellhaas, F. M. H., Burns, M., … Nosek, B. A. (2016). Reducing implicit racial preferences: II. Intervention effectiveness across time. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(8), 1001–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Lehmann-Grube, S. K., Tobisch, A., & Dresel, M. (2024). Changing preservice teacher students’ stereotypes and attitudes and reducing judgment biases concerning students of different family backgrounds: Effects of a short intervention. Social Psychology of Education, 27(4), 1621–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Liu, Z., Rattan, A., & Savani, K. (2023). Reducing gender bias in the evaluation and selection of future leaders: The role of decision-makers’ mindsets about the universality of leadership potential. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(12), 1924–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- * Lucas, B. J., Berry, Z., Giurge, L. M., & Chugh, D. (2021). A longer shortlist increases the consideration of female candidates in male-dominant domains. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(6), 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Lynch, M., Kidd, T., & Shaw, E. (2022). The subtle effects of implicit bias instructions. Law & Policy, 44(1), 98–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T. L., Haw, R. M., Pfeifer, J. E., & Meissner, C. A. (2005). Racial bias in mock juror decision-making: A meta-analytic review of defendant treatment. Law and Human Behavior, 29(6), 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustard, D. B. (2001). Racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in sentencing: Evidence from the U.S. federal courts. The Journal of Law and Economics, 44(1), 285–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Naser, S. C., Brann, K. L., & Noltemeyer, A. (2021). A brief report on the promise of system 2 cues for impacting teacher decision-making in school discipline practices for Black male youth. School Psychology, 36(3), 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Neal, D., Morgan, J. L., Ormerod, T., & Reed, M. W. R. (2024). Intervention to reduce age bias in medical students’ decision making for the treatment of older women with breast cancer: A novel approach to bias training. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 42(1), 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oswald, F. L., Mitchell, G., Blanton, H., Jaccard, J., & Tetlock, P. E. (2013). Predicting ethnic and racial discrimination: A meta-analysis of IAT criterion studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(2), 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, E. L., Porat, R., Clark, C. S., & Green, D. P. (2021). Prejudice reduction: Progress and challenges. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 533–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Pershing, S., Stell, L., Fisher, A. C., & Goldberg, J. L. (2021). Implicit bias and the association of redaction of identifiers with residency application screening scores. JAMA Ophthalmology, 139(12), 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer, J. E., & Ogloff, J. R. P. (1991). Ambiguity and guilt determinations: A modern racism perspective1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21(21), 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Quinn, D. M. (2020). Experimental evidence on teachers’ racial bias in student evaluation: The role of grading scales. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(3), 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehavi, M. M., & Starr, S. B. (2014). Racial disparity in federal criminal sentences. Journal of Political Economy, 122(6), 1320–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Ruva, C. L., Sykes, E. C., Smith, K. D., Deaton, L. R., Erdem, S., & Jones, A. M. (2024). Battling bias: Can two implicit bias remedies reduce juror racial bias? Psychology, Crime & Law, 30(7), 730–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, S., Robertson, C. T., & Baughman, S. B. (2015). Blinding prosecutors to defendants’ race: A policy proposal to reduce unconscious bias in the criminal justice system. Behavioral Science & Policy, 1(2), 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, S., Tannenbaum, D., Cleary, H., Feldman, Y., Glaser, J., Lerman, A., MacCoun, R., Maguire, E., Slovic, P., Spellman, B., Spohn, C., & Winship, C. (2016). Combating biased decisionmaking & promoting justice & equal treatment. Behavioral Science & Policy, 2(2), 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- * Salmanowitz, N. (2018). The impact of virtual reality on implicit racial bias and mock legal decisions. Journal of Law and the Biosciences, 5(1), 174–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, M. J., & Bradfield, A. L. (2004). Race and information processing in criminal trials: Does the defendant’s race affect how the facts are evaluated? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(8), 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, T. (2005). Racial and ethnic disparity in pretrial criminal processing. Justice Quarterly, 22(2), 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, S. R., & Ellsworth, P. C. (2001). White juror bias: An investigation of prejudice against black defendants in the American courtroom. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 7(1), 201–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- * Uhlmann, E. L., & Cohen, G. L. (2005). Constructed criteria: Redefining merit to justify discrimination. Psychological Science, 16(6), 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vela, M. B., Erondu, A. I., Smith, N. A., Peek, M. E., Woodruff, J. N., & Chin, M. H. (2022). Eliminating explicit and implicit biases in health care: Evidence and research needs. Annual Review of Public Health, 43(1), 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- * Wall, E., Narechania, A., Coscia, A., Paden, J., & Endert, A. (2022). Left, right, and gender: Exploring interaction traces to mitigate human biases. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 28(1), 966–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D. M., Levinson, J. D., & Sinnett, S. (2014). Innocent until primed: Mock jurors’ racially biased response to the presumption of innocence. PLoS ONE, 9(3), e92365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| QuADS Domain | Mean | SD | Range | Interpretive Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Theoretical or conceptual underpinning to the research | 2.97 | 0.16 | 2–3 | Frameworks were explicitly stated and applied through design and outcomes. |

| 2. Statement of research aim/s | 2.97 | 0.16 | 2–3 | Aims were clearly and explicitly stated in all studies. |

| 3. Clear description of research setting and target population | 2.58 | 0.50 | 2–3 | Settings/populations were described, though contextual detail was often limited. |

| 4. The study design is appropriate to address the stated research aim/s | 2.32 | 0.47 | 2–3 | Designs matched aims but sometimes relied on simplified formats. |

| 5. Appropriate sampling to address the research aim/s | 1.71 | 0.80 | 1–3 | Most lacked strong sampling justification (power, representativeness, recruitment detail). |

| 6. Rationale for choice of data collection tool/s | 2.50 | 0.51 | 2–3 | Most studies provided a rationale for chosen instruments but lacked psychometric validation details. |

| 7. The format and content of the data collection tool are appropriate to address the stated research aim/s | 2.58 | 0.50 | 2–3 | Tools were appropriate and clear; many were author-designed without psychometrics. |

| 8. Description of data collection procedure | 2.84 | 0.37 | 2–3 | Procedures were clearly described; minor omissions occurred. |

| 9. Recruitment data provided | 2.05 | 0.93 | 1–3 | Recruitment/attrition reporting was uneven and often incomplete. |

| 10. Justification for the analytic method selected | 2.76 | 0.63 | 1–3 | Analytic choices were usually well justified and linked to aims. |

| 11. The method of analysis was appropriate to answer the research aim/s | 2.84 | 0.44 | 1–3 | Analyses were generally suitable for the study design and data type. |

| 12. Evidence that the research stakeholders have been considered in the research design or conduct. | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0–2 | Stakeholder engagement was minimal, noted only in a small subset of applied or participatory studies; substantial involvement was absent. |

| 13. Strengths and limitations critically discussed | 2.45 | 0.55 | 1–3 | Most studies provided reflective discussion of limitations, though the depth varied. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Merla, I.; Gabbert, F.; Scott, A.J. Interventions to Reduce Implicit Bias in High-Stakes Professional Judgements: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111592

Merla I, Gabbert F, Scott AJ. Interventions to Reduce Implicit Bias in High-Stakes Professional Judgements: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111592

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerla, Isabela, Fiona Gabbert, and Adrian J. Scott. 2025. "Interventions to Reduce Implicit Bias in High-Stakes Professional Judgements: A Systematic Review" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111592

APA StyleMerla, I., Gabbert, F., & Scott, A. J. (2025). Interventions to Reduce Implicit Bias in High-Stakes Professional Judgements: A Systematic Review. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111592