Development and Validation of the Future Career Insecurity Scale (FCIS) in Law Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Occupational Future Time Perspective as a Conceptual Lens

1.2. Dimensions of Future Career Insecurity

1.2.1. Future Career Uncertainty

1.2.2. Future Career Self-Doubt

1.2.3. Future Career Anxiety

1.3. Limitations of Existing Measures

1.4. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Item Development and Expert Review

2.2. Translation

2.3. Participants and Setting

2.4. Procedure and Ethics

2.5. Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

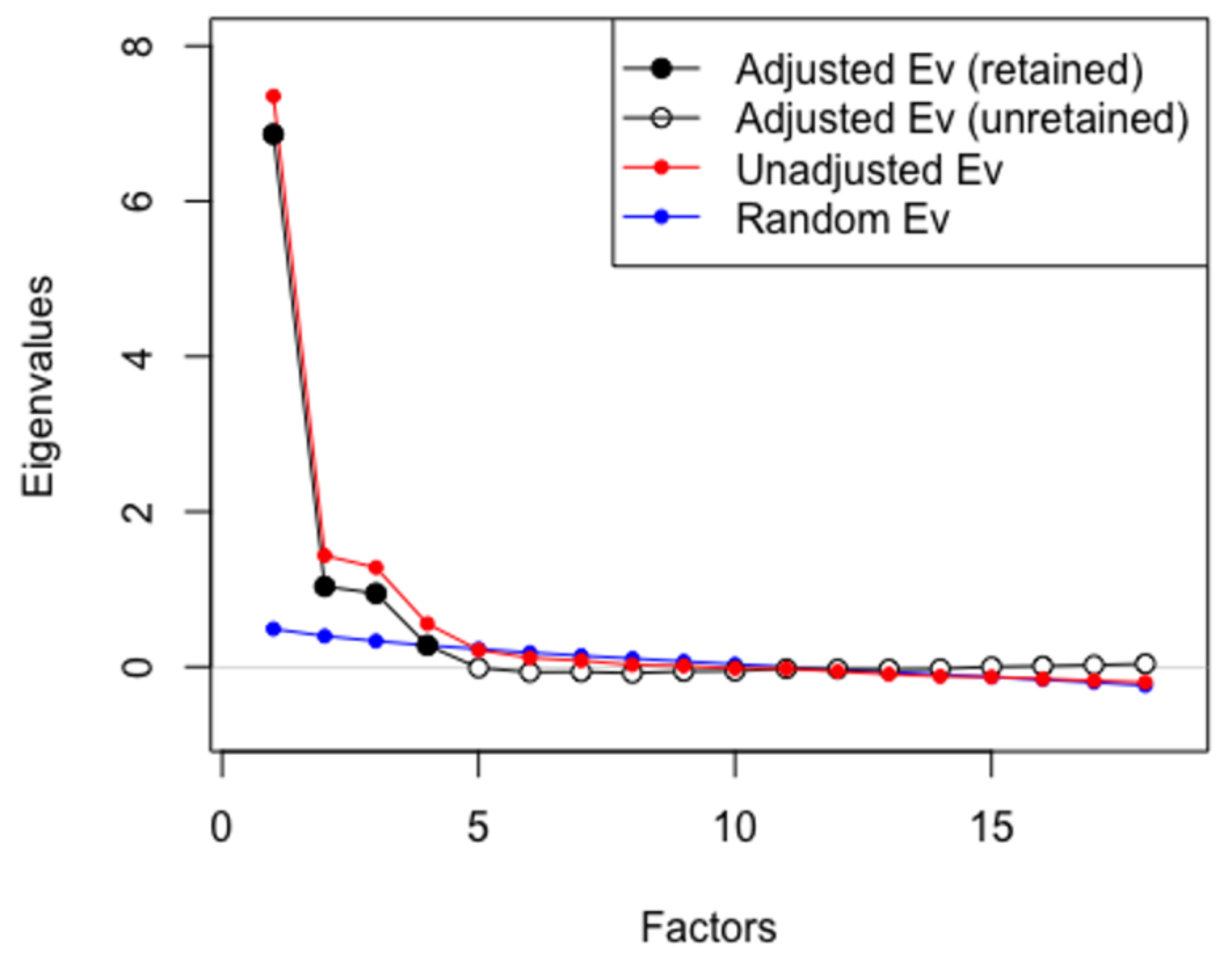

3.1. Study 1: EFA

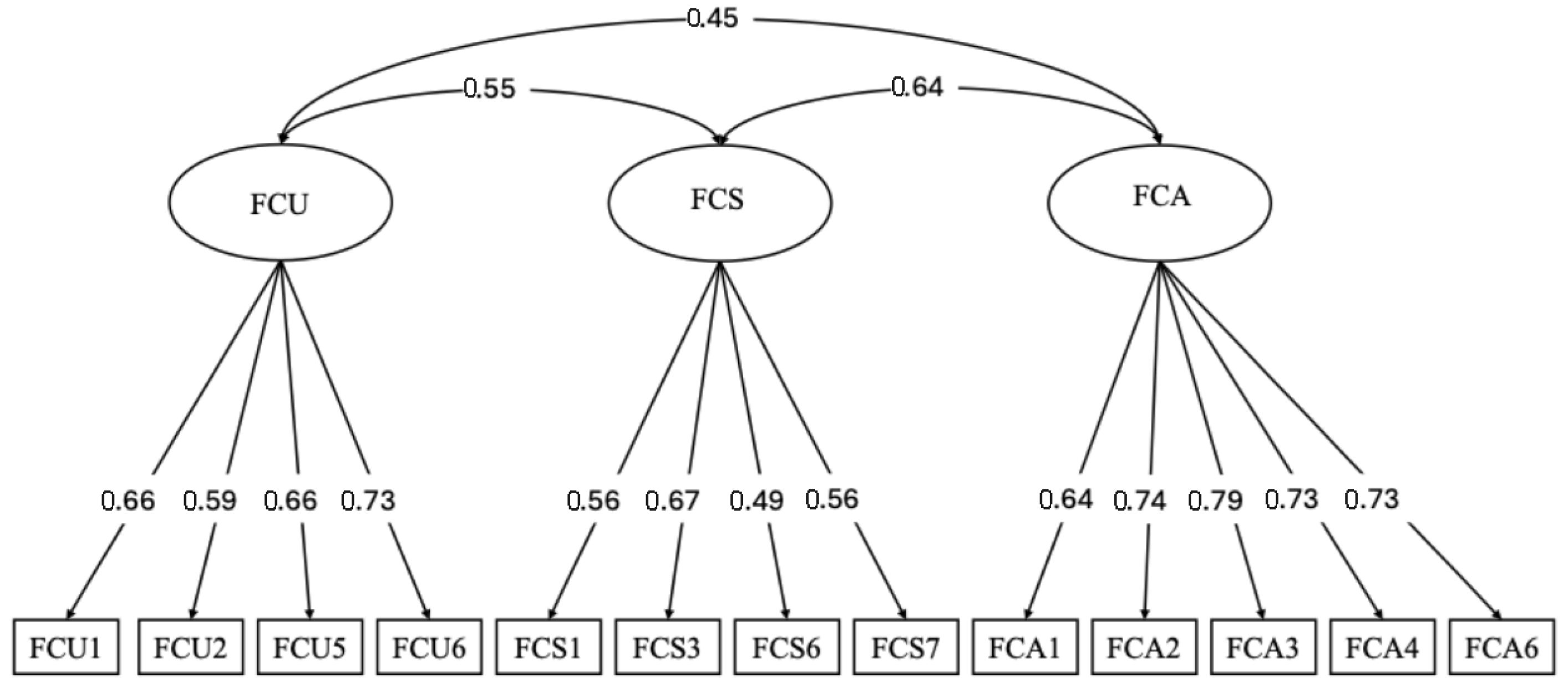

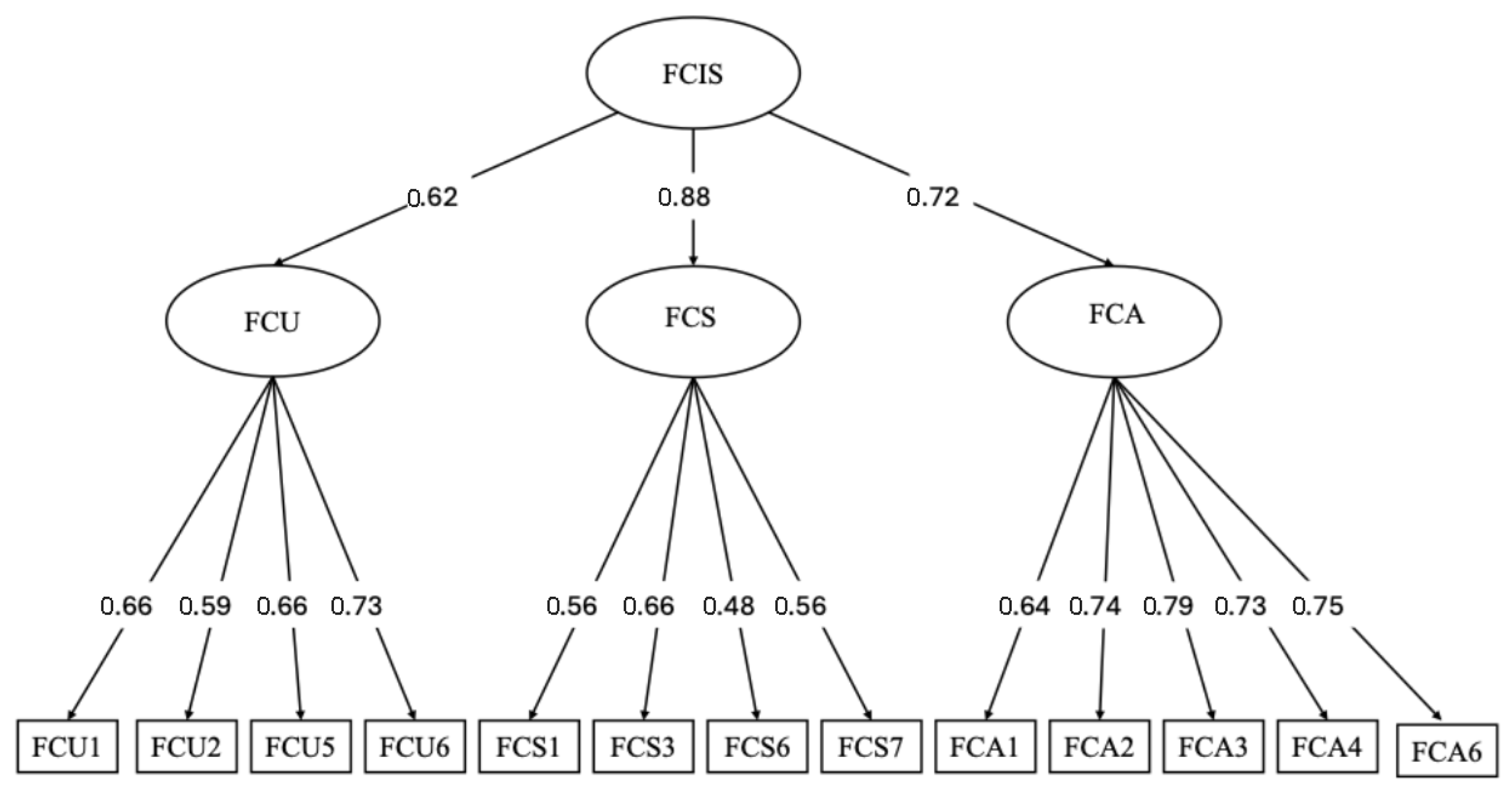

3.2. Study 2: CFA, Internal Consistency, and Convergent Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Positioning Relative to Existing Measures

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| FCIS | Future Career Insecurity Scale |

| FCA | Future Career Anxiety |

| FCU | Future Career Uncertainty |

| FCS | Future Career Self-Doubt |

| DASS-21 | Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales |

| OFTP | Occupational Future Time Perspective |

Appendix A. Initial 19-Item Pool of the FCIS After Expert Review

| Dimensions and Items | |

| Future Career Uncertainty (FCU) | |

| FCU1. | I am uncertain whether my academic achievements (e.g., grades, recognition, and scholarships) accurately signal my abilities to potential employers in law. 我不确定我的学业成就(如成绩、荣誉和奖学金)能否准确向潜在的法律雇主传达我的能力。 |

| FCU2. | I am unsure how my current academic progress will map onto hiring routes in legal practice. 我不清楚当前的学业进展将如何对应法律实务的入职渠道。 |

| FCU3. | I am unclear about my career prospects in law given what my education currently offers. 基于我目前的法学专业学习,我对自己在法律领域的职业前景不够明确。 |

| FCU4. | I am uncertain whether my available financial resources will allow me to pursue the opportunities needed for a successful legal career. 我不确定现有的经济资源是否足以支持我争取迈向成功法律职业所需的机会。 |

| FCU5. | I am unsure about my next steps because my law program has provided fewer career opportunities than I expected. 由于法学专业/法学院学习提供的职业机会少于我的预期,我对下一步该如何规划不确定。 |

| FCU6. | I am uncertain whether the effort I invest now will lead to meaningful opportunities in the legal field. 我不确定自己现在投入的努力是否会带来在法律领域有意义的机会。 |

| Future Career Self-doubt (FCS) | |

| FCS1. | I doubt that my legal reasoning and argumentation are strong enough for professional practice. 我怀疑自己的法律推理与论证能力是否足以胜任专业实践。 |

| FCS2. | I question my competence to handle the responsibilities expected of a junior lawyer. 我质疑自己是否具备承担初级律师应尽职责的能力。 |

| FCS3. | I question whether my current professional connections are sufficient for career advancement. 我质疑自己当前的人脉与职业资源是否足以支持职业晋升。 |

| FCS4. | I am not confident that my coursework and training were rigorous enough to prepare me for real-world legal work. 我不自信自己的课程与训练是否足够严谨,能够让我为真实世界的法律工作做好准备。 |

| FCS5. | I doubt that my law program has prepared me to work confidently and independently in legal practice. 我怀疑法学专业/法学院学习是否使我具备在法律实务中自信且独立工作的能力。 |

| FCS6. | I doubt my contributions in legal discussions or professional settings will be taken seriously. 我质疑自己在法律讨论或职业场合中的观点能否得到应有的重视。 |

| FCS7. | I question whether pursuing law was the right decision for my long-term career. 我质疑攻读法律是否是我长远职业发展的正确选择。 |

| Future Career Anxiety (FCA) | |

| FCA1. | I feel anxious about securing stable or desirable employment in the legal field. 我因能否在法律领域获得稳定或理想的工作而感到焦虑。 |

| FCA2. | I feel tense when I think about meeting the expectations of future employers, colleagues, or clients. 当想到需要满足未来雇主、同事或客户的期望时,我会感到紧张。 |

| FCA3. | I worry about the financial stability of a legal career. 我担心法律职业的经济稳定性。 |

| FCA4. | I feel overwhelmed when I think about the workload and pressure in legal practice. 一想到法律实务的工作量与压力,我就感到不堪重负。 |

| FCA5. | I feel uneasy about whether a legal career will be personally meaningful for me. 我对法律职业是否能让我获得个人意义感到不安。 |

| FCA6. | I feel anxious that my law program has not prepared me well enough for professional success. 我因觉得法学专业/法学院学习没有让我为职业成功做好充分准备而感到焦虑。 |

References

- Alnajjar, H., & Abou Hashish, E. (2024). Exploring the effect of career counseling on nursing students’ employability. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1403730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, P., & Chiesa, R. (2024). University career services and early career outcomes: A systematic review. Social Sciences, 13(9), 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, S., Wang, C., & Kim, M. (2021). Career adaptability, future time perspective, and career anxiety among undergraduate students: A cross-national comparison. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 29, 100328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R. N., Norton, M. P. J., & Asmundson, G. J. (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science, 312(5782), 1913–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S. M., Chung, G. K., Chan, Y. H., Lee, T. S., Chen, J. K., Wong, H., Chung, R. Y., Chen, Y., & Ho, E. S. (2024). Online learning problems, academic worries, social interaction, and psychological well-being among secondary school students in Hong Kong during the COVID-19 pandemic: The socioeconomic and gender differences. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39(3), 2805–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Chui, H., Huang, Y., & King, R. B. (2024). Adaptation and validation of the Chinese version of fear of failure in learning scale. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 42(7), 866–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Li, J., Chui, H., & King, R. B. (2025a). Peer cooperation and competition are both positively linked with mastery-approach goals: An achievement goal perspective. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 941–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Zhou, T., Chui, H., & King, R. B. (2025b). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the performance failure appraisal inventory–short form (PFAI-SF). Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 15(3), 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, H., Pienaar, J., & De Cuyper, N. (2016). Review of 30 years of longitudinal studies on the association between job insecurity and health and well-being: Is there causal evidence? Australian Psychologist, 51(1), 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, E., Balkis, M., & Duru, S. (2023). Procrastination among adults: The role of self-doubt, fear of the negative evaluation, and irrational/rational beliefs. Journal of Evidence-Based Psychotherapies, 23(2), 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, G. (2021). Law-students wellbeing and vulnerability. The Law Teacher, 56(1), 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L., Li, Y., & Pang, W. (2025). Career adaptability and graduates’ mental health: The mediating role of occupational future time perspective in higher education in China. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, N. (2021). The major transitions in professional formation and development from being a student to being a lawyer present opportunities to benefit the students and the law school. Baylor Law Review, 73, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S. (2025). The impact of future time perspective on academic achievement: Mediating roles of academic burnout and engagement. PLoS ONE, 20(1), e0316841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, M. C. (2015). A review of exploratory factor analysis decisions and overview of current practices. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, D., Bender, K. M., & Organ, J. M. (2021). “It is okay to not be okay”: The 2021 survey of law student well-being. University of Louisville Law Review, 60(3), 441–498. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y., Hou, Z. J., Zhang, H., & Xiao, Y. (2022). Future time perspective, career adaptability, anxiety, and career decision-making difficulty: Exploring mediations and moderations. Journal of Career Development, 49(3), 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. J., & von dem Knesebeck, O. (2016). Perceived job insecurity, unemployment and depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 89(4), 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. K., Kramer, A., & Pak, S. (2021). Job insecurity and subjective sleep quality: The role of spillover and gender. Stress and Health, 37(1), 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D. T., Kanfer, R., Betts, M., & Rudolph, C. W. (2018). Future time perspective: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(8), 867–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, L. S. (2002). Institutional denial about the dark side of law school, and fresh empirical guidance for constructively breaking the silence. Journal of Legal Education, 52, 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C., Huang, G. H., & Ashford, S. J. (2018). Job insecurity and the changing workplace: Recent developments and the future trends in job insecurity research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H., & Jeong, D. Y. (2017). Job insecurity and turnover intention: Organizational commitment as mediator. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 45(4), 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2007). The school-to-work transition: A role identity perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(1), 114–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, S. L. (2022). Imposter syndrome & the law school caste system. Pace Law Review, 42(2), 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, J. M., Jaffe, D. B., & Bender, K. M. (2016). Suffering in silence: The survey of law student well-being and the reluctance of law students to seek help for substance use and mental health concerns. Journal of Legal Education, 66(1), 116–156. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J. W., Costello, A. B., & Kellow, J. T. (2008). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis. In Best practices in quantitative methods. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, K., & Bornstein, B. H. (2013). A stressful profession: The experience of attorneys. In Stress, trauma, and wellbeing in the legal system (pp. 217–246). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(1), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L. (2020). Career construction theory and counseling practice. In S. D. Brown, & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (3rd ed., pp. 165–200). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, K. M., & Krieger, L. S. (2004). Does legal education have undermining effects on law students? Evaluating changes in motivation, values, and well-being. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 22(2), 261–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skead, N. K., & Rogers, S. (2014). Stress, anxiety and depression in law students: How what they do affects how they feel. SSRN Electronic Journal, 2392131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D., Strauss, K., & Hirschi, A. (2022). Antecedents and outcomes of work–life uncertainty: A review. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 137, 103743. [Google Scholar]

- Strevens, C., & Lai, Y. L. (2023). From student to practitioner: Exploring the transition into legal practice and the opportunity offered by self-coaching in the management of rejection. In Wellbeing and transitions in law: Legal education and the legal profession (pp. 205–223). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. J., Lu, C. Q., & Lu, L. (2012). Do people with traditional values suffer more from job insecurity? The moderating effects of traditionality. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(1), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S. F. (2021). 2020 law school grads having harder time finding jobs, data shows. ABA Journal. Available online: https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/data-shows-decrease-in-long-term-full-time-jobs-for-2020-law-school-grads (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Yao, C., & McWha-Hermann, I. (2025). Contextualizing career development: Cultural affordances as the missing link in social cognitive career theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 159, 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşlıoğlu, M., Karagülle, A. Ö., & Baran, M. (2013). An empirical research on the relationship between job insecurity, job related stress and job satisfaction in logistics industry. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 99, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B. (2025). Navigating vulnerabilities: An autoethnography of a female Chinese PhD returnee’s job-seeking journey in an age of uncertainty. Journal of Gender Studies, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H., & Frese, M. (2009). Maintaining a focus on opportunities at work: The role of occupational future time perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 583–594. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S., & Yan, Y. (2024). Changes in employment psychology of Chinese university students during the two stages of COVID-19 control and their impacts on their employment intentions. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1447103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X., Tian, G., Yin, H., & He, W. (2021). Is familism a motivator or stressor? Relationships between confucian familism, emotional labor, work-family conflict, and emotional exhaustion among Chinese teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 766047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwick, W. R., & Velicer, W. F. (1986). Comparison of five rules for determining the number of components to retain. Psychological Bulletin, 99(3), 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Future Career Uncertainty (FCU) | ||||

| FCU1. | 3.23 | 0.82 | 0.468 | 0.548 |

| FCU2. | 3.33 | 0.99 | 0.703 | 0.531 |

| FCU3. | 3.30 | 0.86 | 0.554 | 0.546 |

| FCU4. | 3.29 | 0.88 | 0.650 | 0.851 |

| FCU5. | 3.76 | 0.99 | 0.374 | −0.085 |

| FCU6. | 3.59 | 0.93 | 0.444 | 0.197 |

| Future Career Self-doubt (FCS) | ||||

| FCS1. | 3.22 | 0.85 | 0.733 | 1.134 |

| FCS2. | 3.32 | 0.95 | 0.755 | 0.703 |

| FCS3. | 3.26 | 0.79 | 0.604 | 1.054 |

| FCS4. | 3.75 | 0.93 | 0.412 | 0.213 |

| FCS5. | 3.69 | 0.92 | 0.277 | 0.200 |

| FCS6. | 3.48 | 0.85 | 0.577 | 0.797 |

| FCS7. | 3.43 | 0.98 | 0.320 | −0.0227 |

| Future Career Anxiety (FCA) | ||||

| FCA1. | 3.49 | 1.01 | 0.252 | −0.423 |

| FCA2. | 3.57 | 1.04 | 0.144 | −0.551 |

| FCA3. | 3.42 | 1.03 | 0.228 | −0.582 |

| FCA4. | 3.12 | 0.95 | 0.683 | 0.226 |

| FCA5. | 3.49 | 1.03 | 0.268 | −0.406 |

| FCA6. | 3.36 | 1.05 | 0.373 | −0.525 |

| Item | Factor 1: FCA | Factor 2: FCS | Factor 3: FCU |

|---|---|---|---|

| FCA2. I feel tense when I think about meeting the expectations of future employers, colleagues, or clients. 当想到需要满足未来雇主、同事或客户的期望时,我会感到紧张。 | 0.851 | 0.275 | 0.247 |

| FCA1. I feel anxious about securing stable or desirable employment in the legal field. 我因能否在法律领域获得稳定或理想的工作而感到焦虑。 | 0.811 | 0.201 | 0.208 |

| FCA3. I worry about the financial stability of a legal career. 我担心法律职业的经济稳定性。 | 0.78 | 0.27 | 0.286 |

| FCA4. I feel overwhelmed when I think about the workload and pressure in legal practice. 一想到法律实务的工作量与压力,我就感到不堪重负。 | 0.808 | 0.21 | 0.264 |

| FCA5. I feel uneasy about whether a legal career will be personally meaningful for me. 我对法律职业是否能让我获得个人意义感到不安。 | 0.647 | 0.201 | 0.305 |

| FCS7. I question whether pursuing law was the right decision for my long-term career. 我质疑攻读法律是否是我长远职业发展的正确选择 | 0.205 | 0.782 | 0.198 |

| FCS3. I question whether my current professional connections are sufficient for career advancement. 我质疑自己当前的人脉与职业资源是否足以支持职业晋升。 | 0.168 | 0.828 | 0.226 |

| FCS6. I doubt my contributions in legal discussions or professional settings will be taken seriously. 我质疑自己在法律讨论或职业场合中的观点能否得到应有的重视 | 0.332 | 0.57 | 0.314 |

| FCS1. I doubt that my legal reasoning and argumentation are strong enough for professional practice. 我怀疑自己的法律推理与论证能力是否足以胜任专业实践。 | 0.338 | 0.531 | 0.318 |

| FCU2. I am unsure how my current academic progress will map onto hiring routes in legal practice. 我不清楚当前的学业进展将如何对应法律实务的入职渠道。 | 0.216 | 0.241 | 0.871 |

| FCU6. I am uncertain whether the effort I invest now will lead to meaningful opportunities in the legal field. 我不确定自己现在投入的努力是否会带来在法律领域有意义的机会。 | 0.297 | 0.264 | 0.698 |

| FCU1. I am uncertain whether my academic achievements (e.g., grades, recognition, and scholarships) accurately signal my abilities to potential employers in law. 我不确定我的学业成就(如成绩、荣誉和奖学金)能否准确向潜在的法律雇主传达我的能力。 | 0.248 | 0.193 | 0.518 |

| FCU5. I am unsure about my next steps because my law program has provided fewer career opportunities than I expected. 由于法学专业/法学院学习提供的职业机会少于我的预期,我对下一步该如何规划不确定。 | 0.33 | 0.321 | 0.474 |

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. FCIS | – | ||||||

| 2. FCA | 0.742 *** | – | |||||

| 3. FCS | 0.717 *** | 0.695 *** | – | ||||

| 4. FCU | 0.655 *** | 0.697 *** | 0.793 *** | – | |||

| 5. Depression | 0.312 *** | 0.269 *** | 0.364 *** | 0.302 *** | – | ||

| 6. Anxiety | 0.573 *** | 0.559 *** | 0.745 *** | 0.551 *** | 0.677 *** | – | |

| 7. Stress | 0.697 *** | 0.898 *** | 0.636 *** | 0.672 *** | 0.247 *** | 0.491 *** | – |

| Models | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 213.700 *** | 124 | 0.949 | 0.935 | 0.058 | 0.050 | |||

| M2 | 228.949 *** | 144 | 0.951 | 0.947 | 0.052 | 0.054 | 0.002 | 0.012 | 0.004 |

| M3 | 245.380 *** | 157 | 0.949 | 0.950 | 0.051 | 0.055 | −0.002 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| M4 | 263.803 *** | 166 | 0.944 | 0.947 | 0.052 | 0.052 | −0.005 | −0.003 | −0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lan, C.; Weng, X.; Huang, Q.-L.; Yu, L.; Wang, R.; Su, J.; Zhou, T.; Lou, T.; Li, Y.; Li, W. Development and Validation of the Future Career Insecurity Scale (FCIS) in Law Students. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111590

Lan C, Weng X, Huang Q-L, Yu L, Wang R, Su J, Zhou T, Lou T, Li Y, Li W. Development and Validation of the Future Career Insecurity Scale (FCIS) in Law Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111590

Chicago/Turabian StyleLan, Cuiyu, Xinying Weng, Qi-Lu Huang, Liqian Yu, Ruizhe Wang, Jie Su, Tianshu Zhou, Tingjian Lou, Yinlin Li, and Wei Li. 2025. "Development and Validation of the Future Career Insecurity Scale (FCIS) in Law Students" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111590

APA StyleLan, C., Weng, X., Huang, Q.-L., Yu, L., Wang, R., Su, J., Zhou, T., Lou, T., Li, Y., & Li, W. (2025). Development and Validation of the Future Career Insecurity Scale (FCIS) in Law Students. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1590. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111590