From Online Aggression to Offline Silence: A Longitudinal Examination of Bullying Victimization, Dark Triad Traits, and Cyberbullying

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. From Victimization to Cyberbullying

1.2. The Potential Link Between Dark Triad and Cyberbullying

1.3. The Moderating Role of Real-Life Victimization

1.4. The Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Bullying Victimization (BV)

2.2.2. Dark Triad (DT)

2.2.3. Cyberbullying (CB)

2.2.4. Demographic Variables

2.2.5. Common Method Bias

2.3. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

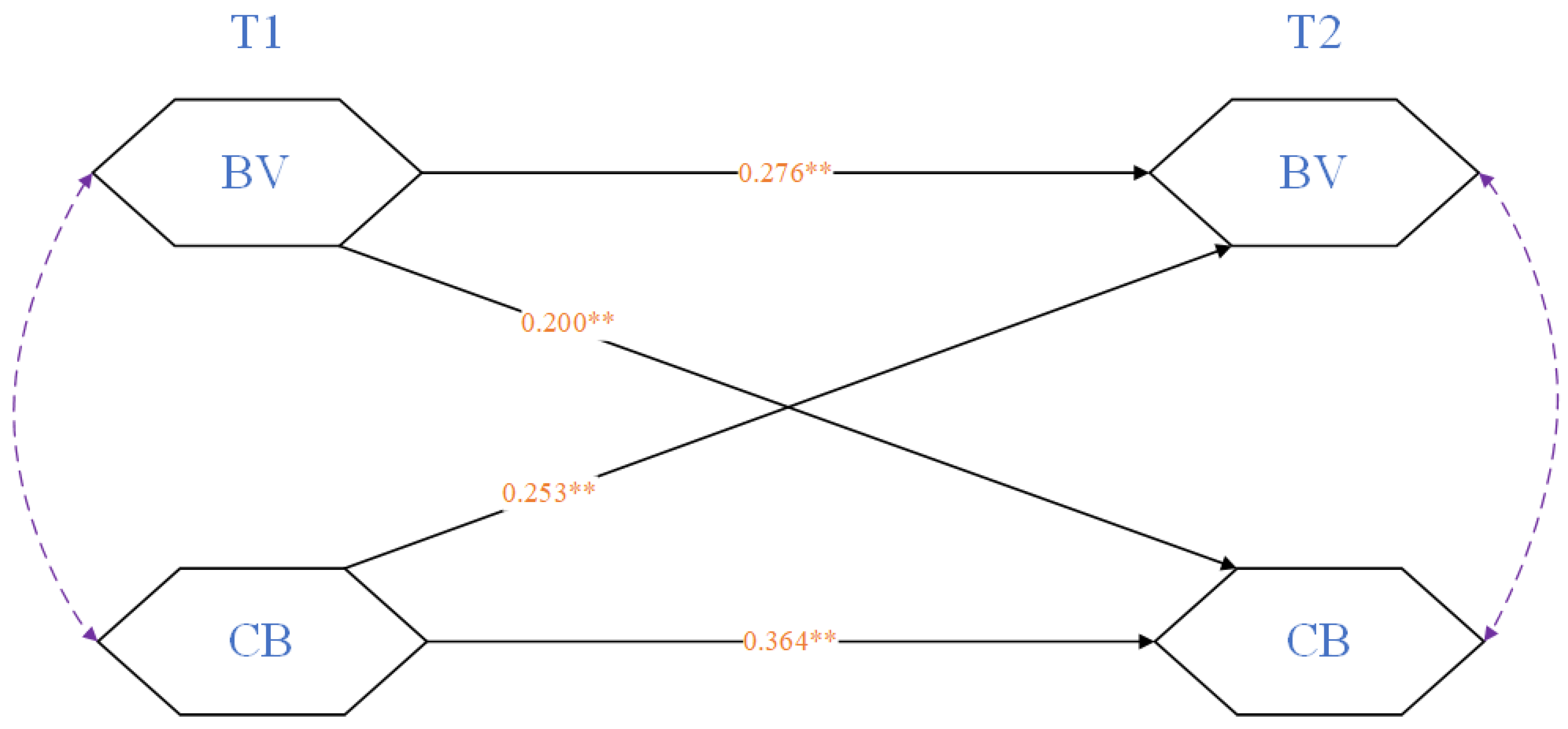

3.2. Study 1: From Victimizations to Cyberbullying

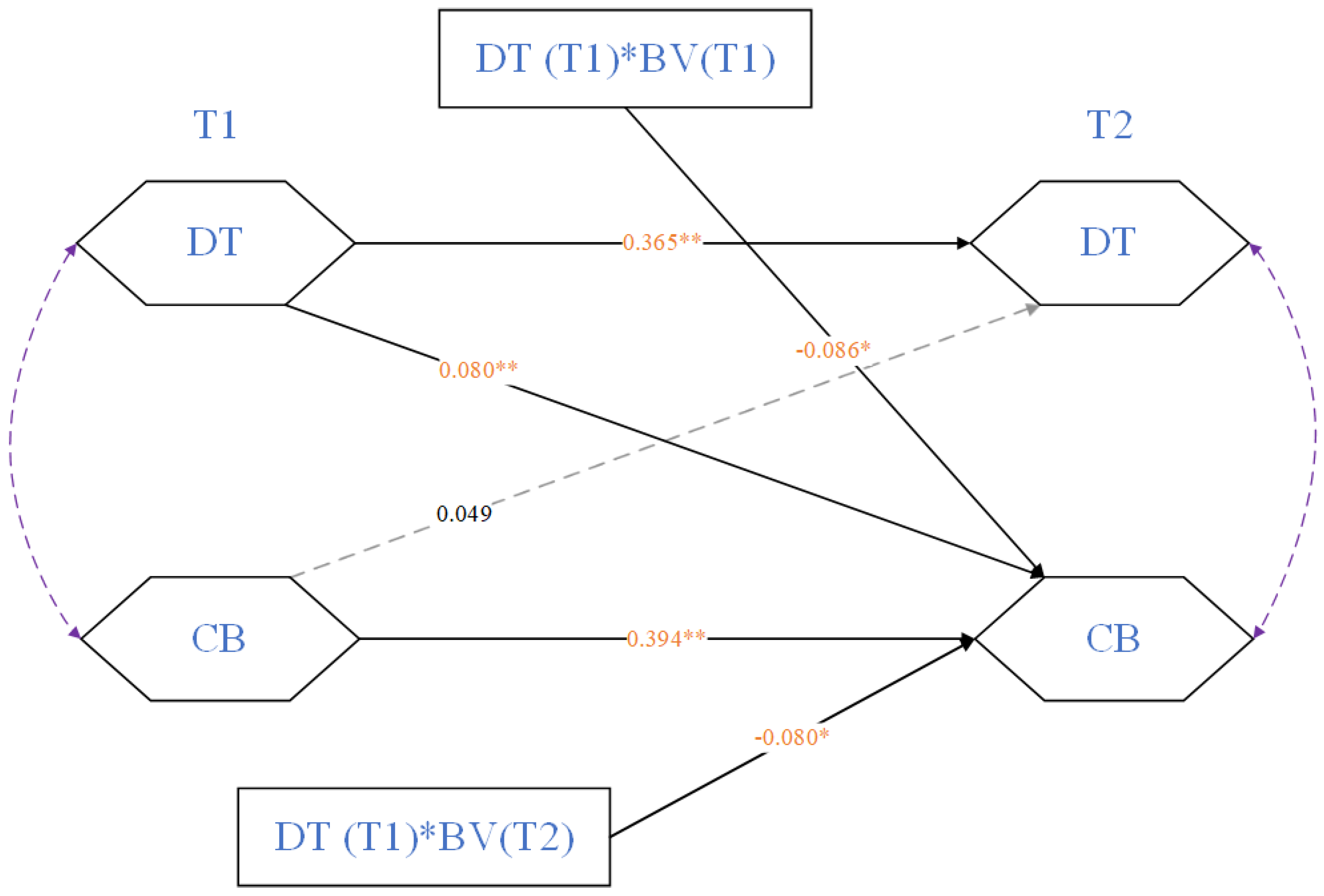

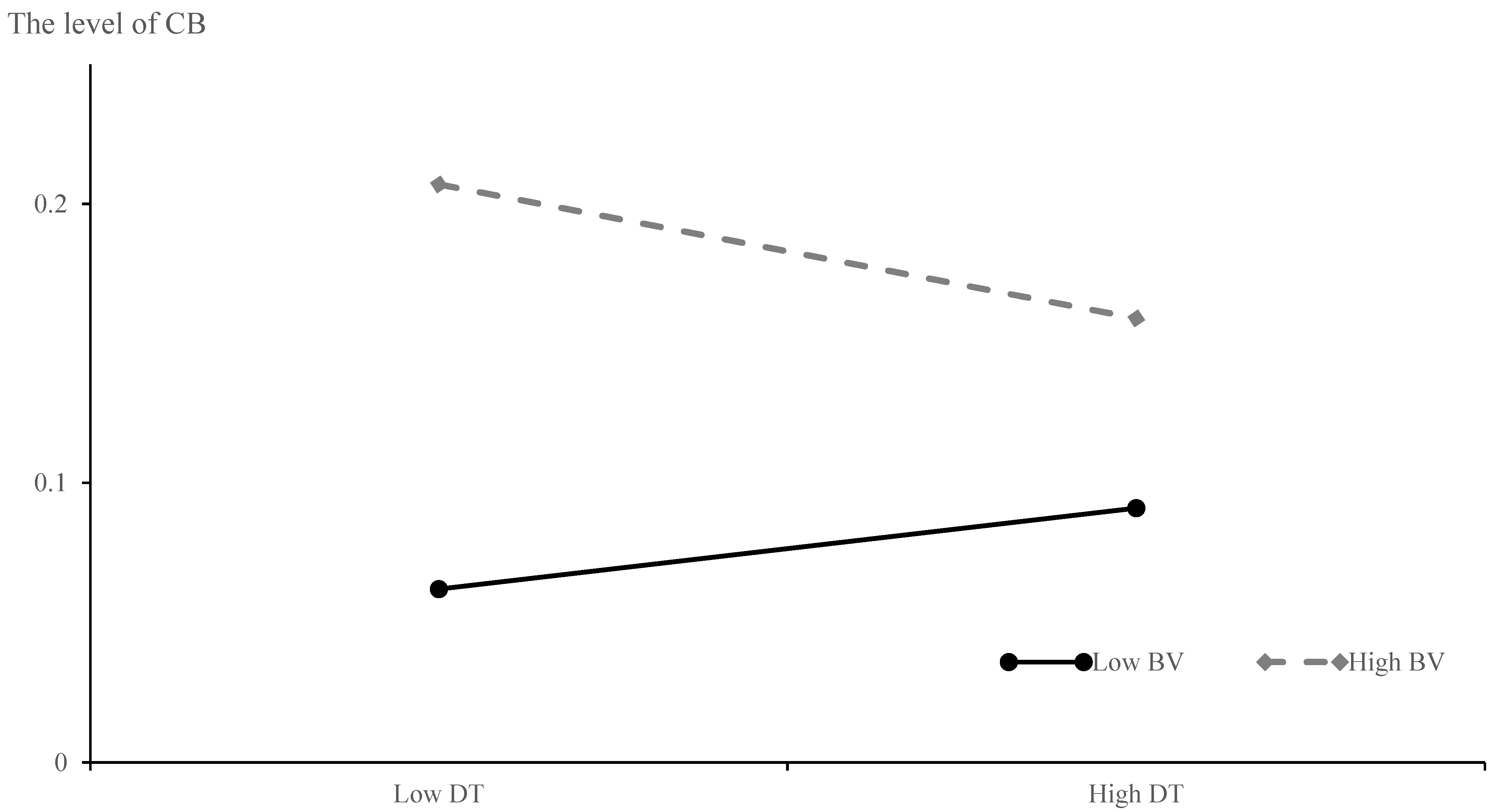

3.3. Study 2: The Moderating Effects of Victimizations

3.4. Additional Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Online Actions over Real-Life Confrontation

4.2. The Process from Bullying Victimization to Cyberbullying

4.3. Dark Triad and Cyberbullying: The Paradox of Victimization

4.4. Implications

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DT | Dark Triad |

| BV | Bullying Victimization |

| CB | Cyberbullying |

References

- Ak, Ş., Özdemir, Y., & Kuzucu, Y. (2015). Cybervictimization and cyberbullying: The mediating role of anger, don’t anger me! Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, C. L., & Hope, D. A. (2015). Fear of negative evaluation, social anxiety and response to positive and negative online social cues. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 39(5), 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleidorn, W., Hopwood, C. J., & Lucas, R. E. (2018). Life events and personality trait change. Journal of Personality, 86(1), 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S., & Glassner, S. (2021). Impacts of low self-control and opportunity structure on cyberbullying developmental trajectories: Using a latent class growth analysis. Crime & Delinquency, 67(4), 601–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B., & Park, S. (2018). Who becomes a bullying perpetrator after the experience of bullying victimization? The moderating role of self-esteem. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(11), 2414–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopherson, K. M. (2007). The positive and negative implications of anonymity in Internet social interactions: “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog”. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(6), 3038–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J., Lee, J., Kim, J., & Lee, S. (2020). An international systematic review of cyberbullying measurements. Computers in Human Behavior, 106, 106485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, W. E., Wolke, D., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2013). Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(4), 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crysel, L. C., Crosier, B. S., & Webster, G. D. (2013). The Dark Triad and risk behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(1), 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, M., Palmiero, M., & D’Amico, S. (2023). The association between Dark Triad and pro-environmental behaviours: The moderating role of trait emotional intelligence (La asociación entre la Tríada Oscura y las conductas proambientales: El papel moderador de la inteligencia emocional rasgo). PsyEcology, 14(3), 338–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodboy, A. K., & Martin, M. M. (2015). The personality profile of a cyberbully: Examining the Dark Triad. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, D., Yanagida, T., Runions, K. C., & Spiel, C. (2021). Why did you do that? Differential types of aggression in offline and in cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 128, 107107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampejs, V., Zwickl, A. A., Tran, U. S., & Voracek, M. (2025). The Dark Triad of personality and criminal and delinquent behavior: Preregistered systematic review and three-level meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 246, 113308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S. C., Boyle, J. M., & Warden, D. (2004). Help seeking amongst child and adolescent victims of peer-aggression and bullying: The influence of school-stage, gender, victimisation, appraisal, and emotion. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74 Pt 3, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, L., Hawdon, J., Huang, B., & others. (2020). Preconditions for guardianship interventions in cyberbullying: Incident interpretation, collective and automated efficacy, and relative popularity of bullies. Computers in Human Behavior, 113, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. E., Chang, C.-H., & Lord, R. G. (2006). Moving from cognition to behavior: What the research says. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 381–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the Dark Triad. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D. N., & Figueredo, A. J. (2013). The core of darkness: Uncovering the heart of the Dark Triad. European Journal of Personality, 27(6), 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Introducing the Short Dark Triad (SD3): A brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment, 21(1), 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapanos, E., Teixeira, P., & Gouveia, R. (2016). Need fulfillment and experiences on social media: A case on Facebook and Whatsapp. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(Pt B), 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E., & Glomb, T. M. (2014). Victimization of high performers: The roles of envy and work group identification. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostovicova, D., & Knott, E. (2022). Harm, change and unpredictability: The ethics of interviews in conflict research. Qualitative Research, 22(1), 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R. M., & Limber, S. P. (2013). Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(Suppl. 1), S13–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L. T., & Li, Y. (2013). The validation of the R-Victimisation Scale (E-VS) and the E-Bullying Scale (E-BS) for adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc, K., Nagar, P. M., Caivano, O., & Talwar, V. (2022). “The thing is, it follows you everywhere”: Child and adolescent conceptions of cyberbullying. Computers in Human Behavior, 130, 107180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, A., & Schroeder, J. (2020). Two social lives: How differences between online and offline interaction influence social outcomes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, C., Xu, D., & Chen, G. (2024). Dark and blue: A meta-analysis of the relationship between Dark Triad and depressive symptoms. Journal of Research in Personality, 114, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79(5), 1013–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M. J., Nakano, T., Enomoto, A., & Suda, T. (2012). Anonymity and roles associated with aggressive posts in an online forum. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(3), 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, H. K., Bradshaw, C. P., & Kush, J. M. (2018). Adjustment outcomes of victims of cyberbullying: The role of personal and contextual factors. Journal of School Psychology, 70, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nail, P. R., Simon, J. B., Bihm, E. M., Greer, T., & Van Leeuwen, M. D. (2016). Defensive egotism and bullying: Gender differences yield qualified support for the compensation model of aggression. Journal of School Violence, 15(1), 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q., Yang, C., Stomski, M., Zhao, Z., Teng, Z., & Guo, C. (2022). Longitudinal link between bullying victimization and bullying perpetration: A multilevel moderation analysis of perceived school climate. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(13–14), NP12238–NP12259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, R., & Matsumoto-Oda, A. (2022). HEXACO, Dark Triad and altruism in daily life. Personality and Individual Differences, 185, 111303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 751–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B., Li, T., Ji, L., Qin, L., & Zhang, W. (2021). Why does classroom-level victimization moderate the association between victimization and depressive symptoms? The “healthy context paradox” and two explanations. Child Development, 92(5), 1836–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, F., & Matos, M. (2016). Cyber-stalking victimization: What predicts fear among Portuguese adolescents? European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 22(2), 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Edgar, K., Bar-Haim, Y., McDermott, J. M., Chronis-Tuscano, A., Pine, D. S., & Fox, N. A. (2010). Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion, 10(3), 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S. M., Bardeen, J. R., & Orcutt, H. K. (2011). Experiential avoidance as a moderator of the relationship between behavioral inhibition system sensitivity and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(8), 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J., & Gan, X. (2025a). The potential roles of social ostracism and loneliness in the development of dark triad traits in adolescents: A longitudinal study. Journal of Personality. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J., & Gan, X. (2025b). When love constrains: The impact of parental psychological control on dark personality development in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 238, 113093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J., Gan, X., Pu, Z., Jin, X., Zhu, X., & Wei, C. (2024). The healthy context paradox between bullying and emotional adaptation: A moderated mediating effect. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 1661–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J., Lu, Z., & Gan, X. (2025). Through a dark lens: A longitudinal study on Dark Triad traits, future negative insight, and antisocial attitudes. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 53(11), 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, J. M., Bonniot-Cabanac, M. C., & Cabanac, M. (2005). Can aggression provide pleasure? European Psychologist, 10(2), 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösner, L., & Krämer, N. C. (2016). Verbal venting in the social web: Effects of anonymity and group norms on aggressive language use in online comments. Social Media + Society, 2(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, S. V., & Camadan, F. (2016). The new face of violence tendency: Cyber bullying perpetrators and their victims. Computers in Human Behavior, 59, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P., Harris, P. R., & Epton, T. (2014). Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychological Bulletin, 140(2), 511–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonje, R., Smith, P. K., & Frisén, A. (2013). The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearer, S. M., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis–stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritt, S. M., Ryder, A. G., Ring, A. J., & Pincus, A. L. (2010). Pathological narcissism and the depressive temperament. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(3), 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, N., Polat, O., Karapirli, M., Uysal, C., & Turan, G. S. (2011). The new violence type of the era: Cyber bullying among university students. Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research, 17(1), 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geel, M., Goemans, A., Toprak, F., & Vedder, P. (2017). Which personality traits are related to traditional bullying and cyberbullying? A study with the Big Five, Dark Triad and sadism. Personality and Individual Differences, 106, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, A., Simpson, E. G., Gagnon, S., & Ohannessian, C. M. (2020). Social media use and risky behaviors in adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 79, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vismara, M., Girone, N., Conti, D., Nicolini, G., & Dell’Osso, B. (2022). The current status of cyberbullying research: A short review of the literature. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 46, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranda, M. N., Doraiswamy, P., Prabhu, J. R., Ajayan, A., & Priyankadevi, S. (2023). Content analysis of cyberbullying coverage in Newspapers—A study from Bengaluru, India. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 32(2), 456–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederhold, B. K. (2024). The dark side of the digital age: How to address cyberbullying among adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 27(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A. E., Rao, I. H., Jain, N. P., Gronbeck, C., Sloan, B., Grant-Kels, J. M., & Hao Feng, M. (2024). Ethics of Doxxing and Cyberbullying in Dermatology. Clinics in Dermatology, 42(6), 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C., Huang, S., Evans, R., & Zhang, W. (2021). Cyberbullying among adolescents and children: A comprehensive review of the global situation, risk factors, and preventive measures. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 634909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., Zhou, Z., Chu, X., Lei, Y., & Fan, C. (2019). The Trajectory from Traditional Bullying Victimization to Cyberbullying: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27(3), 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, I., Baldry, A. C., Farrington, D. P., & Llorent, V. J. (2019). Are children involved in cyberbullying low on empathy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of research on empathy versus different cyberbullying roles. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 45, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T1 BV | T2 BV | T1 DT | T2 DT | T1 CB | T2 CB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 BV | - | |||||

| T2 BV | 0.394 ** | - | ||||

| T1 DT | 0.215 ** | 0.146 ** | - | |||

| T2 DT | 0.134 ** | 0.115 ** | 0.363 ** | - | ||

| T1 CB | 0.467 ** | 0.382 ** | 0.218 ** | 0.095 * | - | |

| T2 CB | 0.216 ** | 0.397 ** | 0.149 * | 0.198 ** | 0.385 ** | - |

| M | 1.206 | 1.223 | 2.481 | 2.553 | 0.087 | 0.136 |

| SD | 0.385 | 0.433 | 0.997 | 1.189 | 0.425 | 0.507 |

| Model | χ2 | CFI | ΔCFI | RMSEA | SRMR | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| configural | 6.314 | 0.989 | 0.064 | 0.027 | ||

| metric | 7.555 | 0.985 | −0.004 | 0.055 | 0.032 | −0.009 |

| scalar | 10.074 | 0.983 | −0.002 | 0.048 | 0.046 | −0.007 |

| M1 | 2.391 | 0.997 | 0.047 | 0.015 | ||

| M2 | 37.524 | 0.954 | 0.094 | 0.032 |

| T2 BV | T2 CB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | p | b | SE | β | p | |

| T1 BV | 0.311 | 0.046 | 0.276 | <0.001 | 0.264 | 0.053 | 0.200 | <0.001 |

| T1 CB | 0.257 | 0.042 | 0.253 | <0.001 | 0.433 | 0.051 | 0.364 | <0.001 |

| T2 DT | T2 CB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | β | p | b | SE | β | p | |

| T1 DT | 0.435 | 0.045 | 0.365 | <0.001 | 0.067 | 0.019 | 0.080 | 0.031 |

| T1 CB | 0.049 | 0.109 | 0.018 | 0.653 | 0.472 | 0.049 | 0.394 | <0.001 |

| T1 DT × T1 BV | −0.100 | 0.047 | −0.086 | 0.033 | ||||

| T1 DT × T2 BV | −0.074 | 0.037 | −0.080 | 0.041 | ||||

| T2 DT | T2 BV | T2 CB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | |

| T1 BV | 0.131 | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.394 | 0.035 | <0.001 | 0.176 | 0.040 | <0.001 |

| T1 DT | 0.337 | 0.035 | <0.001 | 0.046 | 0.036 | 0.209 | 0.058 | 0.043 | 0.176 |

| T2 DT | 0.127 | 0.039 | <0.001 | ||||||

| χ2 | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | ||||||

| Model Fit | 7.447 | 0.996 | 0.029 | 0.023 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Gan, X.; Pu, J. From Online Aggression to Offline Silence: A Longitudinal Examination of Bullying Victimization, Dark Triad Traits, and Cyberbullying. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111583

Zhang S, Wang J, Gan X, Pu J. From Online Aggression to Offline Silence: A Longitudinal Examination of Bullying Victimization, Dark Triad Traits, and Cyberbullying. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111583

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shaojie, Jiaxiang Wang, Xiong Gan, and Junwei Pu. 2025. "From Online Aggression to Offline Silence: A Longitudinal Examination of Bullying Victimization, Dark Triad Traits, and Cyberbullying" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111583

APA StyleZhang, S., Wang, J., Gan, X., & Pu, J. (2025). From Online Aggression to Offline Silence: A Longitudinal Examination of Bullying Victimization, Dark Triad Traits, and Cyberbullying. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111583