The Impact of AI Guide Language Strategies on Museum Visitor Experience: The Mediating Role of Psychological Distance in the Arousal–Topic Fit Effect

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Language Expectancy Theory

2.2. The Impact of Language Arousal on Satisfaction with AI Digital Guides and the Research Hypotheses for Its Mediating Mechanisms

2.3. The Impact of Language Arousal on Emotional Resonance with AI Digital Guides and the Research Hypotheses for Its Mediating Mechanisms

2.4. The Impact of Language Arousal on Knowledge Recall After Using AI Digital Guides and the Research Hypotheses for Its Mediating Mechanisms

2.5. The Moderated Role of the Popular Science Topic

3. Research Methods

3.1. Participants

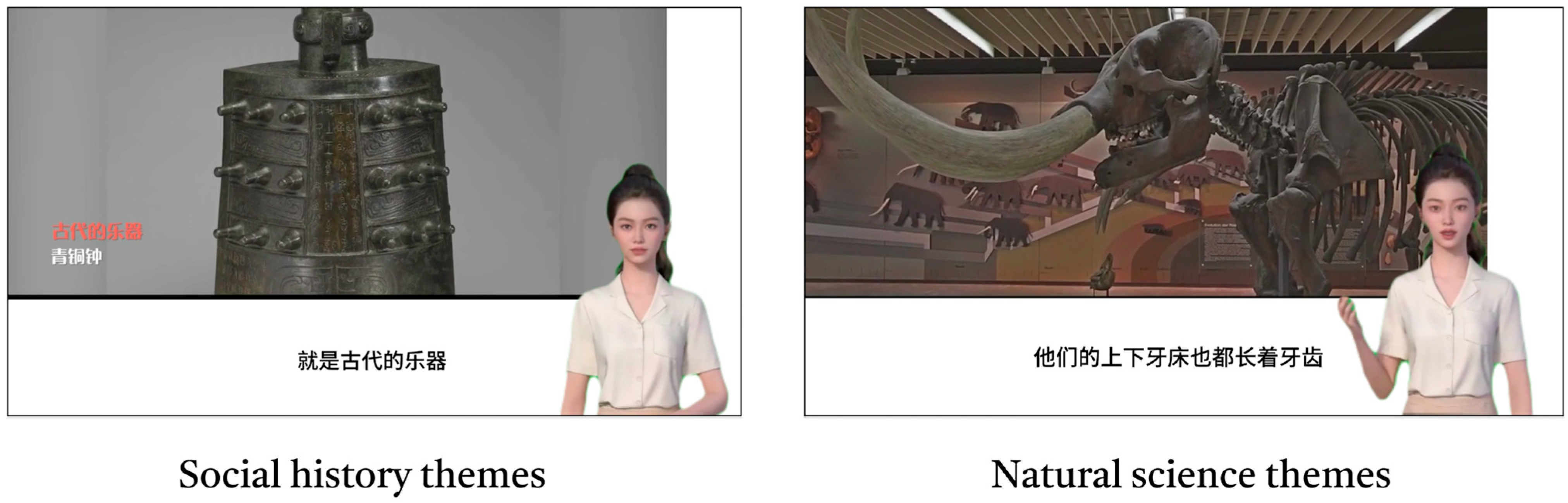

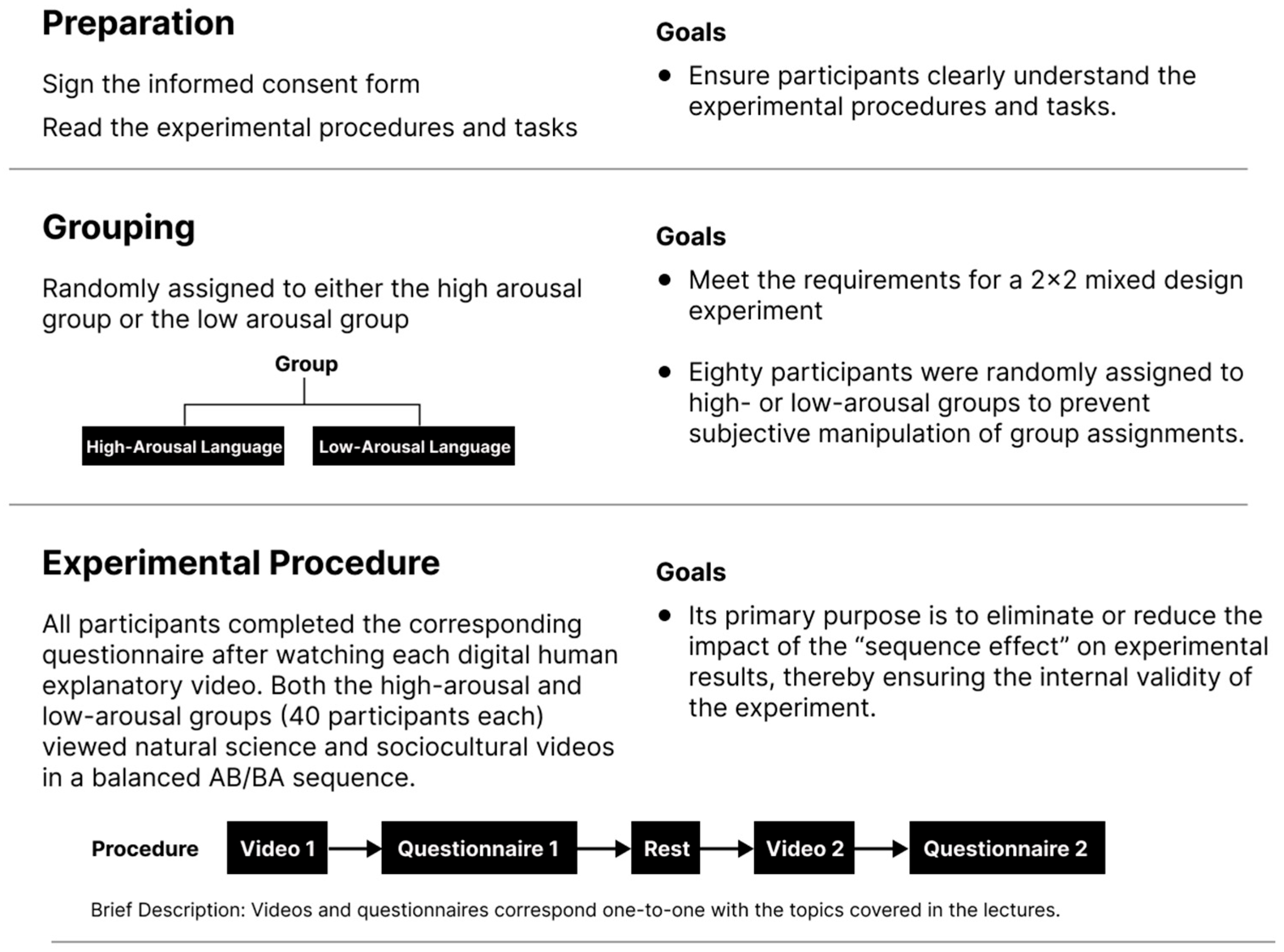

3.2. Experimental Design, Experimental Materials and Equipment

3.3. Measuring Tools

3.3.1. Psychological Distance Scale

3.3.2. Emotional Resonance Scale

3.3.3. Concentration Scale

3.3.4. Satisfaction Scale

3.3.5. Continuous Use Intention Scale

3.4. Experimental Procedures

3.5. Data Processing Methods

4. Results

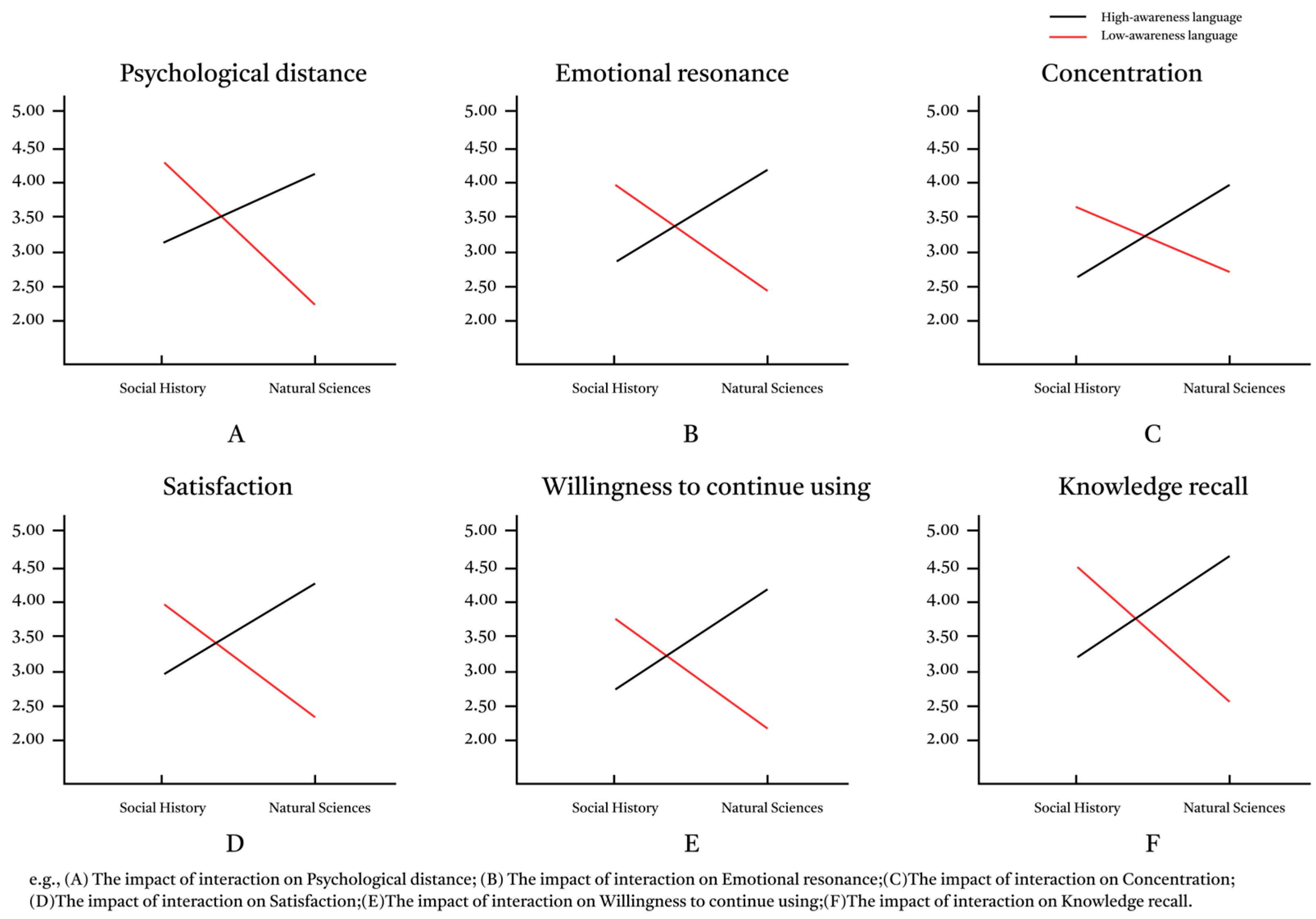

4.1. Analysis of Differences Between Groups in Behavioral Measurements

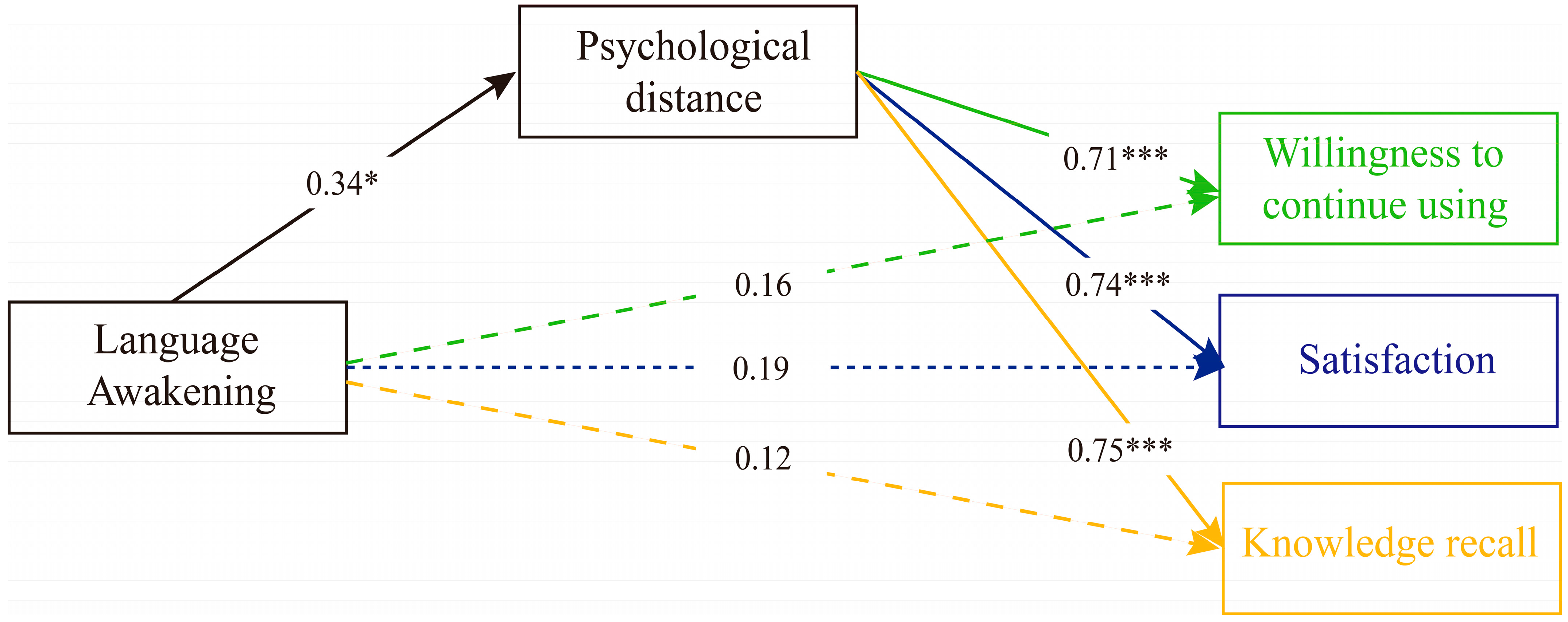

4.2. Mediation Effect Analysis

4.2.1. The Mediating Effect of Psychological Distance

4.2.2. The Mediating Effect of Emotional Resonance

4.2.3. The Mediating Effect of Concentration

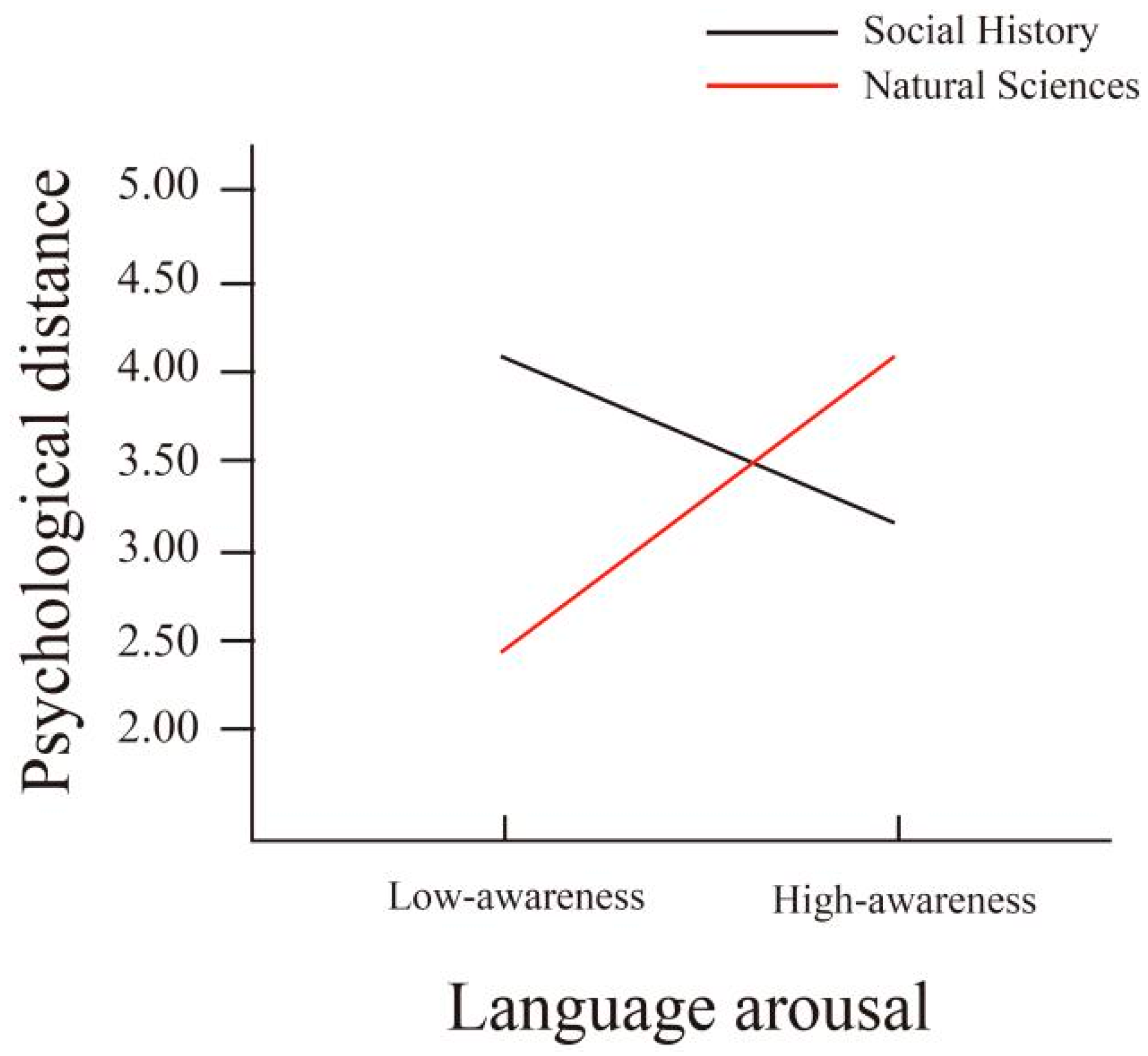

4.3. Moderated Mediation Effect

4.3.1. Moderated Mediation Effect of Language Arousal → Psychological Distance → Satisfaction

4.3.2. Moderated Mediation Effect of Language Arousal → Psychological Distance → Continued Use Intention/Knowledge Recall

5. Discussion

5.1. Relationship Between Language Arousal and AI Digital Guide Satisfaction, Willingness to Continue Using, and Knowledge Recall

5.2. The Mediating Role of Psychological Distance, Emotional Resonance, and Concentration

5.3. The Regulatory Role of the Subject Matter

5.4. Limitations and Shortcomings

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Item | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological distance | I think the information provided by the digital human narrator is reliable | (Chen et al., 2024) and (Li & Sung, 2021) |

| I think this digital human narrator is trustworthy | ||

| I am willing to interact with/respond to this digital human explainer frequently | ||

| I agree with the professional knowledge and capabilities of this AI digital human tour guide | ||

| I enjoyed watching the digital human guide’s museum tours. | ||

| Emotional resonance | Through the explanation of the digital human tour guide, I can clearly understand the historical background/scientific significance of the exhibits. | Escalas and Stern (2003) |

| The guided tour made me realize the cultural value and natural laws behind the exhibits. | ||

| I tried to use the information in the tour guide to speculate on the role of the exhibits in the social/ecological system at that time. | ||

| The tour guide helped me sort out the logical connections between different exhibits (such as timeline and species evolution). | ||

| I can use the knowledge gained from the guided tour to explain to others the uniqueness of these exhibits. | ||

| While listening to the tour guide, I felt like I was in the historical site/natural environment. | ||

| The guide’s narrative shocked me about the wisdom of the ancients and the evolution of life. | ||

| I felt a similar emotional resonance with the creators of the exhibits (ancient people/nature). | ||

| At the end of the tour, I was still immersed in the cultural/natural atmosphere conveyed by the exhibition. | ||

| I felt the human destiny/ecological stories behind the exhibits had an emotional impact on me. | ||

| Concentration | When the digital human explains the museum, I can block out most distractions. | Li and Yang (2016) and Lu and Yang (2018) |

| When the digital human explains the museum, I focus on learning the content. | ||

| As the digital human explains the museum, I am immersed in the current task. | ||

| I was easily distracted by other things while the digital man was explaining the museum. | ||

| My attention is not easily distracted when the digital man explains the museum. | ||

| Continuous Use Intention | If possible, I plan to use this digital tour guide when I visit museums in the future. | Xie et al. (2025) |

| If possible, I plan to use this digital guide more often when visiting museums in the future. | ||

| I will recommend this museum digital guide to my friends. | ||

| Satisfaction | In this type of museum tour, I am very satisfied with the language style of the digital tour guide. | W.-T. Wang et al. (2019) |

| The digital human guide’s language style met my expectations for this type of museum tour. | ||

| In this type of museum tour, I was very satisfied with the experience of using the language style of this digital human tour guide. | ||

| In this type of museum tour, the digital tour guide’s language style was satisfactory in meeting my needs. |

References

- Aichouche, R., Chergui, K., Brika, S. K. M., El Mezher, M., Musa, A., & Laamari, A. (2022). Exploring the relationship between organizational culture types and knowledge management processes: A meta-analytic path analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 856234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altweck, L., & Marshall, T. C. (2015). When you have lived in a different culture, does returning ‘Home’ not feel like home? Predictors of psychological readjustment to the heritage culture. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0124393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryani, A., Isbilen, E. S., & Christiansen, M. H. (2020). Affective arousal links sound to meaning. Psychological Science, 31(8), 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A. (2020). Myths of the Odyssey in the British Museum (and beyond): Jane Ellen Harrison’s museum talks and their audience. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, 63(1), 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, K. (2020). Family, memory and emotion in the museum. Emotion, Space and Society, 35, 100679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D. (2020). Lessons from glen burnie: Queering a historic house museum. Journal of Museum Education, 45(4), 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J., Moe, W. W., & Schweidel, D. A. (2023). What holds attention? Linguistic drivers of engagement. Journal of Marketing, 87(5), 793–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoon, M., Pauls, V., & Roberts, D. L. (2002). Language expectancy theory. In J. Dillard, & M. Pfau (Eds.), The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice (pp. 117–136). SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio Rizzo, G. L., Villarroel Ordenes, F., Pozharliev, R., De Angelis, M., & Costabile, M. (2024). How high-arousal language shapes micro- versus macro-influencers’ impact. Journal of Marketing, 88(4), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S., & Suh, J. (2025). The impact of VR exhibition experiences on presence, interaction, immersion, and satisfaction: Focusing on the experience economy theory (4Es). Systems, 13(1), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Shao, B., Yang, X., Kang, W., & Fan, W. (2024). Avatars in live streaming commerce: The influence of anthropomorphism on consumers’ willingness to accept virtual live streamers. Computers in Human Behavior, 156, 108216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H., & Kim, S. (2023). Proposal of smart guide system for cultural heritage of archaeological sites using IoT-focusing on Hoeamsa Temple site in Yangju, Korea. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering, 20(5), 8745–8765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citron, F. M. M., Cacciari, C., Funcke, J. M., Hsu, C.-T., & Jacobs, A. M. (2019). Idiomatic expressions evoke stronger emotional responses in the brain than literal sentences. Neuropsychologia, 131, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo, C. F., & Aquino Junior, P. T. (2014). Psychological personas for universal user modeling in human-computer interaction. In M. Kurosu (Ed.), Human-computer interaction. Theories, methods, and tools (Vol. 8510, pp. 3–13). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rojas, C., & Camarero, C. (2008). Visitors’ experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: Evidence from an interpretation center. Tourism Management, 29(3), 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, J., & Van Der Walt, K. (2023). Die ontstaan van lewe: 《In die begin was die Woord daar》. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe, 63(2), 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J. E., & Stern, B. B. (2003). Sympathy and empathy: Emotional responses to advertising dramas. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(4), 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q., Shanthikumar, J. G., & Xue, M. (2022). Consumer choice models and estimation: A review and extension. Production and Operations Management, 31(2), 847–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C., Dissanayake, T., Hosoda, K., Maekawa, T., & Ishiguro, H. (2020, February 3–5). Similarity of speech emotion in different languages revealed by a neural network with attention. 2020 IEEE 14th International Conference on Semantic Computing (ICSC) (pp. 381–386), San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruyama, S., Saito, Y., & Hirata, D. (2025). Requirements for natural history museums to become cultural institutions: From the science council of Japan’s public symposium “Considering Natural History Museums as Cultural Facilities”. Journal of Geography (Chigaku Zasshi), 134(1), 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herhausen, D., Ludwig, S., Grewal, D., Wulf, J., & Schoegel, M. (2019). Detecting, preventing, and mitigating online firestorms in brand communities. Journal of Marketing, 83(3), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetland, P. (2019). Constructing publics in museums’ science communication. Public Understanding of Science, 28(8), 958–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W., Leong, Y. C., & Ismail, N. A. (2023). The influence of communication language on purchase intention in consumer contexts: The mediating effects of presence and arousal. Current Psychology, 43, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Li, Y., & Tian, F. (2025). Enhancing user experience in interactive virtual museums for cultural heritage learning through extended reality: The case of Sanxingdui bronzes. IEEE Access, 13, 59405–59421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T., Gan, X., Liang, Z., & Luo, G. (2022). AIDM: Artificial intelligent for digital museum autonomous system with mixed reality and software-driven data collection and analysis. Automated Software Engineering, 29(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C., Hine, D. W., & Marks, A. D. G. (2017). The future is now: Reducing psychological distance to increase public engagement with climate change. Risk Analysis, 37(2), 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D. R., Graham-Engeland, J. E., Smyth, J. M., & Lehman, B. J. (2018). Clarifying the associations between mindfulness meditation and emotion: Daily high- and low-arousal emotions and emotional variability. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 10(3), 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kefi, H., Besson, E., Zhao, Y., & Farran, S. (2024). Toward museum transformation: From mediation to social media-tion and fostering omni-visit experience. Information & Management, 61(1), 103890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzun, D., Varfolomeyev, A., Yalovitsyna, S., & Volokhova, V. (2017). Semantic infrastructure of a smart museum: Toward making cultural heritage knowledge usable and creatable by visitors and professionals. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 21(2), 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kum, J., & Lee, M. (2022). Can gestural filler reduce user-perceived latency in conversation with digital humans? Applied Sciences, 12(21), 10972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, N.-T., Cheng, Y.-S., Chang, K.-C., & Hu, S.-M. (2018). Assessing the asymmetric impact of interpretation environment service quality on museum visitor experience and post-visit behavioral intentions: A case study of the National Palace Museum. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(7), 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H., Choi, Y., Zhao, X., Hua, M., Wang, W., Garaj, V., & Lam, B. (2024). How immersive and interactive technologies affect the user experience and cultural exchange in the museum and gallery sector. The International Journal of the Inclusive Museum, 18(1), 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Sung, Y. (2021). Anthropomorphism brings us closer: The mediating role of psychological distance in User–AI assistant interactions. Computers in Human Behavior, 118, 106680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., & Yang, X. (2016). Effects of learning styles and interest on concentration and achievement of students in mobile learning. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 54(7), 922–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2014). Traversing psychological distance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(7), 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindquist, K. A. (2021). Language and emotion: Introduction to the special issue. Affective Science, 2(2), 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D., He, P., & Yan, H. (2023). An empirical study of schema-associated mnemonic method for classical Chinese poetry in primary and secondary education based on cognitive schema migration theory. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 20720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., & Wang, S. (2024). A study of the effect of viewing online health popular science information on users’ willingness to change health behaviors—Based on the psychological distance perspective. Current Psychology, 43(38), 30135–30147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Mi, G., & Shmelova-Nesterenko, O. (2023). Research on immersive scenario design in museum education. In P. Zaphiris, A. Ioannou, R. A. Sottilare, J. Schwarz, F. Fui-Hoon Nah, K. Siau, J. Wei, & G. Salvendy (Eds.), HCI international 2023—Late breaking papers (Vol. 14060, pp. 167–175). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobban, J., & Murphy, D. (2020). Military museum collections and art therapy as mental health resources for veterans with PTSD. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(4), 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveys, K., Sagar, M., & Broadbent, E. (2020). The effect of multimodal emotional expression on responses to a digital human during a self-disclosure conversation: A computational analysis of user language. Journal of Medical Systems, 44(9), 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T., & Yang, X. (2018). Effects of the visual/verbal learning style on concentration and achievement in mobile learning. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 14(5), 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, S., De Ruyter, K., Friedman, M., Brüggen, E. C., Wetzels, M., & Pfann, G. (2013). More than words: The influence of affective content and linguistic style matches in online reviews on conversion rates. Journal of Marketing, 77(1), 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, C., Bento, M., & Lencastre, J. A. (2025). Immersive virtual learning spaces for emotional engagement in education with the classroom-ready virtual reality device CLASS VR. In J. M. Krüger, D. Pedrosa, D. Beck, M.-L. Bourguet, A. Dengel, R. Ghannam, A. Miller, A. Peña-Rios, & J. Richter (Eds.), Immersive learning research network (Vol. 2271, pp. 460–470). Springer Nature Switzerland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massara, F., & Severino, F. (2013). Psychological distance in the heritage experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 42, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, K., & Bickle, S. (2017). Digital storytelling and the ‘problem’ of sentimentality. Media International Australia, 165(1), 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S., & Kahn, B. (2002). Cross-category effects of induced arousal and pleasure on the internet shopping experience. Journal of Retailing, 78(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J., Thoma, G.-B., Kampschulte, L., & Köller, O. (2023). Openness to experience and museum visits: Intellectual curiosity, aesthetic sensitivity, and creative imagination predict the frequency of visits to different types of museums. Journal of Research in Personality, 103, 104352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J. K. (2017). Museum communication and storytelling: Articulating understandings within the museum structure. Museum Management and Curatorship, 32(5), 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niikuni, K., Wang, M., Makuuchi, M., Koizumi, M., & Kiyama, S. (2022). Pupil dilation reflects emotional arousal via poetic language. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 129(6), 1691–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nook, E. C., Schleider, J. L., & Somerville, L. H. (2017). A linguistic signature of psychological distancing in emotion regulation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146(3), 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, W. I., Houser, K., Stone, R., & White, M. (2018). Digital storytelling in early childhood: Student illustrations shaping social interactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombini, A. (2017). Storytelling and telling history. Towards a grammar of narratives for Cultural Heritage dissemination in the Digital Era. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 24, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y., Yang, K., Wilson, K., Hong, Z., & Lin, H. (2020). The impact of museum interpretation tour on visitors’ engagement and post-visit conservation intentions and behaviours. International Journal of Tourism Research, 22(5), 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlovsky, L. (2013). Language and cognition—Joint acquisition, dual hierarchy, and emotional prosody. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 7, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietroni, E. (2025). Multisensory museums, hybrid realities, narration, and technological innovation: A discussion around new perspectives in experience design and sense of authenticity. Heritage, 8(4), 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripatti-Torniainen, L., & Stevanovic, M. (2023). University teaching development workshops as sites of joint decision-making: Negotiations of authority in academic cultures. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 38, 100681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J., & Tian, L. (2025). The psychological resonance of place: Spatial narratives and identity in the historical educational landscapes of Rongxiang, China. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 59(2), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasenko, A., Kaestner, E., Rodriguez, J., Benjamin, C., Winstanley, F. S., Sepeta, L., Horsfall, J., Bookheimer, S. Y., Shih, J. J., Norman, M. A., Gooding, A., & McDonald, C. R. (2025). Neural (re)organisation of language and memory: Implications for neuroplasticity and cognition. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 96(5), 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelmaszczyk, M., Pierscieniak, A., & Krawczyk-Sokolowska, I. (2025). Visitor orientation as a game changer for the digital transformation of museums. Museum Management and Curatorship, 40(1), 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, E. (Christine), Danny Han, D.-I., Bae, S., & Kwon, O. (2022). What drives technology-enhanced storytelling immersion? The role of digital humans. Computers in Human Behavior, 132, 107246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tastemirova, A., Schneider, J., Kruse, L. C., Heinzle, S., & Brocke, J. V. (2022). Microexpressions in digital humans: Perceived affect, sincerity, and trustworthiness. Electronic Markets, 32(3), 1603–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N. M., Van Reekum, C. M., & Chakrabarti, B. (2022). Cognitive and affective empathy relate differentially to emotion regulation. Affective Science, 3(1), 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trémolière, B., Gagnon, M.-È., & Blanchette, I. (2016). Cognitive load mediates the effect of emotion on analytical thinking. Experimental Psychology, 63(6), 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, M. E., Cengiz, S., & Aksoy, Ş. (2025). Empathy and life satisfaction among adolescent in Türkiye: Examining mediating roles of resilience and self-esteem. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Han, Y., Kandampully, J., & Lu, X. (2025). How language arousal affects purchase intentions in online retailing? The role of virtual versus human influencers, language typicality, and trust. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 82, 104106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Wang, G., Zhang, J., & Wang, X. (2021). Interpreting disaster: How interpretation types predict tourist satisfaction and loyalty to dark tourism sites. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 22, 100656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Ye, Z., & Zhu, S. (2023). Research on college students’ emotional experience in online learning. International Journal of Continuing Engineering Education and Life-Long Learning, 33(6), 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Li, J., Sun, G., Cheng, Z., & Zhang, X. (2017). Achievement goals and life satisfaction: The mediating role of perception of successful agency and the moderating role of emotion reappraisal. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 30(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-T., Ou, W.-M., & Chen, W.-Y. (2019). The impact of inertia and user satisfaction on the continuance intentions to use mobile communication applications: A mobile service quality perspective. International Journal of Information Management, 44, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2025). Artificial intelligence-driven interactive experience for intangible cultural heritage: Sustainable innovation of blue clamp-resist dyeing. Sustainability, 17(3), 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidlich, J., Yau, J., & Kreijns, K. (2024). Social presence and psychological distance: A construal level account for online distance learning. Education and Information Technologies, 29(1), 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C., Xie, Y., Wang, Y., Zhou, P., Lu, L., Feng, Y., & Liang, C. (2025). Understanding older adults’ continued-use intention of AI voice assistants. Universal Access in the Information Society, 24(2), 1687–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X., Li, Y., Liu, S., & Liu, M. (2025). Learning from museums: Resource scarcity in museum interpretations and sustainable consumption intention. Annals of Tourism Research, 112, 103955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y., & Rui, J. R. (2024). Who likely experiences reactance to quitting messages: How individual cultural identification moderates the effect of controlling language on psychological reactance. Patient Education and Counseling, 123, 108245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D., Bond, S. D., & Zhang, H. (2017). Keep your cool or let it out: Nonlinear effects of expressed arousal on perceptions of consumer reviews. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(3), 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., & Bowman, D. A. (2022). Exploring effect of level of storytelling richness on science learning in interactive and immersive virtual reality. ACM International Conference on Interactive Media Experiences, 3, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Van Lieshout, L. L. F., Colizoli, O., Li, H., Yang, T., Liu, C., Qin, S., & Bekkering, H. (2025). A cross-cultural comparison of intrinsic and extrinsic motivational drives for learning. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 25(1), 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L., Miao, M., & Gan, Y. (2020). Perceived control buffers the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on general health and life satisfaction: The mediating role of psychological distance. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 12(4), 1095–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| High Arousal Group | Low Arousal Group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social History | Natural Sciences | Social History | Natural Sciences | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| psychological distance | 3.120 | 0.776 | 4.040 | 0.507 | 4.085 | 0.477 | 2.400 | 0.818 |

| Emotional resonance | 2.775 | 0.769 | 4.078 | 0.406 | 3.980 | 0.525 | 2.455 | 0.761 |

| Concentration | 2.515 | 0.640 | 3.910 | 0.512 | 3.625 | 0.525 | 2.645 | 0.633 |

| Satisfaction | 2.913 | 0.986 | 4.125 | 0.494 | 3.875 | 0.686 | 2.275 | 0.820 |

| Continuous Use Intention | 2.624 | 0.810 | 4.090 | 0.565 | 3.742 | 0.677 | 2.175 | 0.712 |

| Knowledge recall | 3.180 | 1.196 | 4.650 | 1.027 | 4.500 | 0.961 | 3.730 | 1.373 |

| Dependent Variable | Effect | F | p | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Distance | Language Arousal (A) | 13.180 | <0.001 | 0.145 |

| Topic (T) | 10.997 | 0.001 | 0.124 | |

| A × T | 284.128 | <0.001 | 0.646 | |

| Emotional Resonance | Language Arousal (A) | 4.768 | 0.032 | 0.058 |

| Topic (T) | 2.841 | 0.094 | 0.018 | |

| A × T | 289.969 | <0.001 | 0.650 | |

| Concentration | Language Arousal (A) | 0.721 | 0.398 | 0.009 |

| Topic (T) | 5.048 | 0.027 | 0.061 | |

| A × T | 176.588 | <0.001 | 0.531 | |

| Satisfaction | Language Arousal (A) | 16.736 | <0.001 | 0.177 |

| Topic (T) | 3.421 | 0.067 | 0.021 | |

| A × T | 199.484 | <0.001 | 0.561 | |

| Continued Use Intention | Language Arousal (A) | 14.023 | <0.001 | 0.154 |

| Topic (T) | 3.109 | 0.080 | 0.020 | |

| A × T | 246.927 | <0.001 | 0.614 | |

| Knowledge Recall | Language Arousal (A) | 5.027 | 0.028 | 0.061 |

| Topic (T) | 0.844 | 0.360 | 0.005 | |

| A × T | 115.202 | <0.001 | 0.425 |

| Arousal Condition | Dependent Variable | Topic | t | p | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |||||||

| High Arousal | Nat. Sci. | Soc. His. | |||||

| Psychological Distance | 4.04 (0.507) | 3.12 (0.776) | 5.93 | <0.001 | [0.64, 2.10] | 1.05 | |

| Emotional Resonance | 4.08 (0.406) | 2.78 (0.769) | 13.29 | <0.001 | [1.19, 1.41] | 1.96 | |

| Concentration | 3.91 (0.512) | 2.52 (0.640) | 13.29 | <0.001 | [1.19, 1.60] | 2.35 | |

| Satisfaction | 4.13 (0.494) | 2.91 (0.986) | 9.80 | <0.001 | [0.91, 1.51] | 1.52 | |

| Cont. Use Intention | 4.09 (0.565) | 2.62 (0.810) | 12.32 | <0.001 | [1.27, 1.67] | 1.96 | |

| Knowledge Recall | 4.65 (1.027) | 3.18 (1.196) | 8.72 | <0.001 | [1.17, 1.77] | 1.32 | |

| Low Arousal | Nat. Sci. | Soc. His. | |||||

| Psychological Distance | 2.40 (0.818) | 4.09 (0.477) | 10.34 | <0.001 | [−2.10, −0.64] | 1.68 | |

| Emotional Resonance | 2.46 (0.761) | 3.98 (0.437) | 15.59 | <0.001 | [1.43, 1.63] | 2.31 | |

| Concentration | 2.65 (0.633) | 3.63 (0.525) | 9.80 | <0.001 | [0.78, 1.18] | 1.72 | |

| Satisfaction | 2.28 (0.820) | 3.88 (0.686) | 12.34 | <0.001 | [1.30, 1.90] | 2.11 | |

| Cont. Use Intention | 2.18 (0.712) | 3.74 (0.677) | 13.75 | <0.001 | [1.37, 1.77] | 2.31 | |

| Knowledge Recall | 2.58 (1.059) | 4.50 (0.961) | 10.10 | <0.001 | [1.62, 2.22] | 1.83 | |

| Path Relationship | Coefficient | Standard Error | p-Value | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language Arousal → Satisfaction | 0.19 | 0.13 | >0.05 | Unsupported |

| Language Arousal → Continued Use Intention | 0.16 | 0.13 | >0.05 | Unsupported |

| Psychological Distance → Satisfaction | 0.74 | 0.07 | <0.001 | Supported |

| Psychological Distance → Continued Use Intention | 0.71 | 0.07 | <0.001 | Supported |

| Language Arousal × Popular Science Topic → Psychological Distance | 2.61 | 0.21 | <0.001 | Supported |

| Predictor | Outcome: Continued Use Intention | Outcome: Knowledge Recall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Standard Error | p-Value | Coefficient | Standard Error | p-Value | |

| Language Arousal | 0.16 | 0.13 | >0.05 | 0.12 | 0.19 | >0.05 |

| Psychological Distance | 0.71 | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.75 | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Language Arousal × Topic | 2.61 | 0.21 | <0.001 | 2.61 | 0.21 | <0.001 |

| R2 | 0.447 | 0.287 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, T.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, A.; Liu, Z.; Fan, M. The Impact of AI Guide Language Strategies on Museum Visitor Experience: The Mediating Role of Psychological Distance in the Arousal–Topic Fit Effect. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111569

Xia T, Wu Y, Qiu A, Liu Z, Fan M. The Impact of AI Guide Language Strategies on Museum Visitor Experience: The Mediating Role of Psychological Distance in the Arousal–Topic Fit Effect. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111569

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Tiansheng, Yujiao Wu, Aopeng Qiu, Ziyu Liu, and Meng Fan. 2025. "The Impact of AI Guide Language Strategies on Museum Visitor Experience: The Mediating Role of Psychological Distance in the Arousal–Topic Fit Effect" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111569

APA StyleXia, T., Wu, Y., Qiu, A., Liu, Z., & Fan, M. (2025). The Impact of AI Guide Language Strategies on Museum Visitor Experience: The Mediating Role of Psychological Distance in the Arousal–Topic Fit Effect. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1569. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111569