All Eyes on the New, but Who Hears the Old? The Impact of Incumbent Employees’ Perceived Status Threat on Work Behavior

Abstract

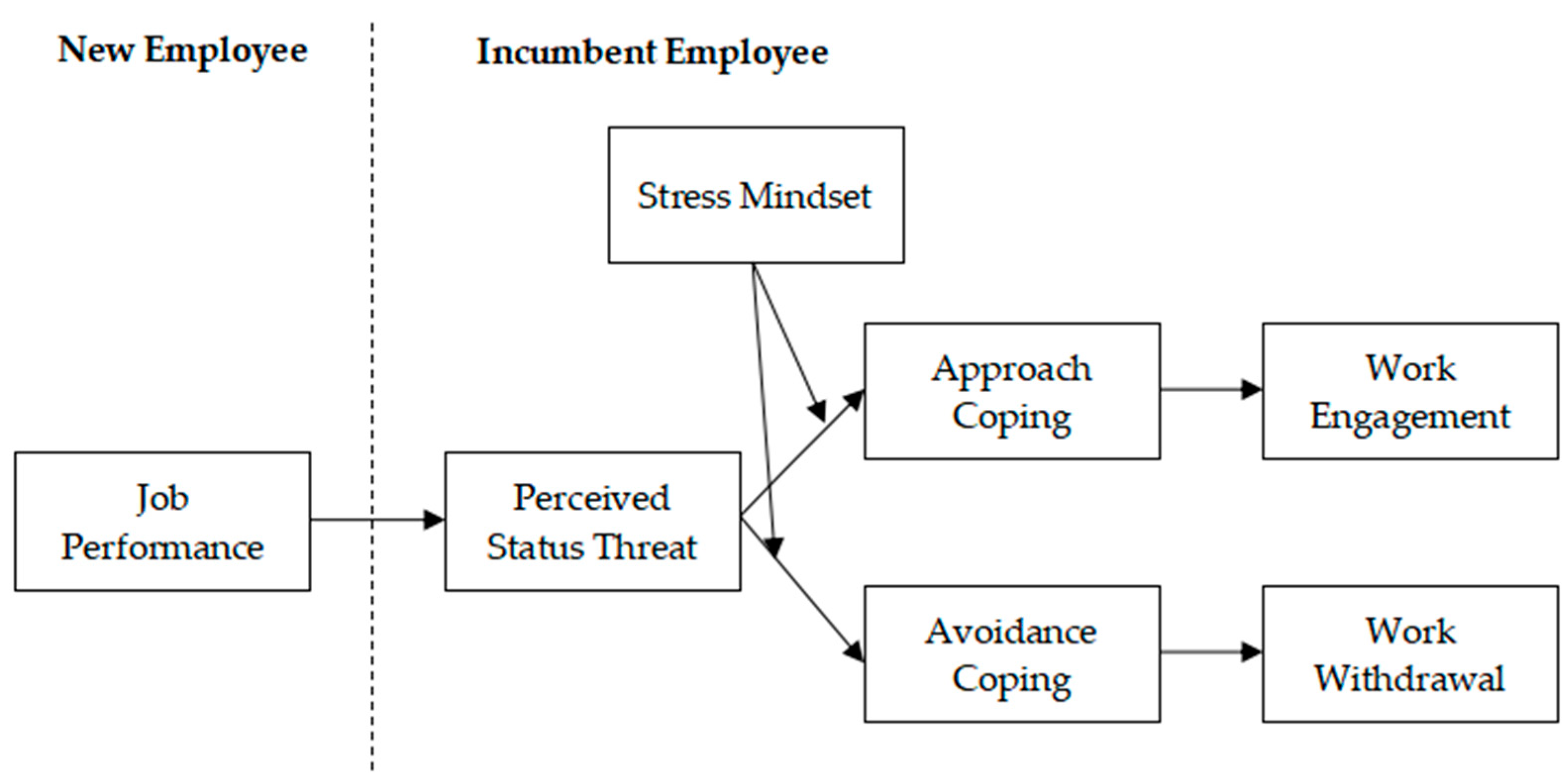

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Cognitive Appraisal Theory of Stress

2.2. New Employees’ Job Performance and Incumbent Employees’ Perceived Status Threat

2.3. Incumbent Employees’ Perceived Status Threat and Work Behavior

2.4. The Mediating Role of Approach Coping and Avoidance Coping

2.5. The Moderating Role of Stress Mindset

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measurements

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Common Method Variance Tests

4.3. Descriptive Analyses

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

4.4.1. Main Effects and Mediating Effects

4.4.2. Moderating Effects and Moderated Mediation Effects of the Stress Mindset

4.4.3. Sequential Mediating Effects

4.4.4. Moderated Sequential Mediation Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C., Angus, D., Hildreth, J., & Howland, L. (2015). Is the desire for status a fundamental human motive? A review of the empirical literature. Psychological Bulletin, 141(3), 574–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C., & Kilduff, G. J. (2009). The pursuit of status in social groups. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(5), 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C., Willer, R., Kilduff, G. J., & Brown, C. E. (2012). The origins of deference: When do people prefer lower status? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(5), 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshel, M. H., Kang, M., & Miesner, M. (2010). The approach-avoidance framework for identifying athletes’ coping style as a function of gender and race. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51(4), 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K., & Douglas, S. (2003). Identity threat and antisocial behavior in organizations: The moderating effects of individual differences, aggressive modeling, and hierarchical status. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 90(1), 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M., Leenders, R., Oldham, G. R., & Vadera, A. K. (2010). Win or lose the battle for creativity: The power and perils of intergroup competition. Academy of Management Journal, 53(4), 827–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F. (2017). Beyond dominance and competence: A moral virtue theory of status attainment. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 21(3), 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendersky, C., & Hays, N. A. (2012). Status conflict in groups. Organization Science, 23(2), 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendersky, C., & Pai, J. (2018). Status dynamics. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J., Cohen, B. P., & Zelditch, M., Jr. (1972). Status Characteristics and Social Interaction. American Sociological Review, 37(3), 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J., Rosenholtz, S. J., & Zelditch, M. (1980). Status organizing processes. Annual Review of Sociology, 6(1), 479–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blader, S. L., & Chen, Y. R. (2012). Differentiating the Effects of status and power: A justice perspective. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 102(5), 994–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliese, P. D., Edwards, J. R., & Sonnentag, S. (2017). Stress and well-being at work: A century of empirical trends reflecting theoretical and societal influences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D. J., Ferris, D. L., Heller, D., & Keeping, L. M. (2007). Antecedents and consequences of the frequency of upward and downward social comparisons at work. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 102(1), 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, E. R. (2012). The risks and rewards of speaking up: Managerial responses to employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 851–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E. M., Liao, H., Chuang, A., Zhou, J., & Dong, Y. (2017). Hot shots and cool reception? An expanded view of social consequences for high performers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(5), 845–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S., & White, T. L. (1994). Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(2), 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Paterson, N. L., Stadler, M. J., & Saks, A. M. (2014). The relative importance of proactive behaviors and outcomes for predicting newcomer learning, well-being, and work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(3), 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, A. J., Akinola, M., Martin, A., & Fath, S. (2017). The role of stress mindset in shaping cognitive, emotional, and physiological responses to challenging and threatening stress. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 30(4), 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, A. J., Salovey, P., & Achor, S. (2013). Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 716–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. D. (2015). Electromyographic analysis of responses to third person intergroup threat. Journal of Social Psychology, 155(2), 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Ponte, A., Li, L., Ang, L., Lim, N., & Seow, W. J. (2024). Evaluating SoJump.com as a tool for online behavioral research in China. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 41, 100905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A. M., Nifadkar, S. S., Bauer, T. N., & Erdogan, B. (2017). Examining managers’ perception of newcomer proactive behavior during organizational socialization. Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, 2017(1), 10592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.-L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support—Employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5), 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschi, M. (2000). Double standards for competence: Theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y., Huang, J.-C., & Farh, J.-L. (2009). Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. The Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P., Stoner, J., Hochwarter, W., & Kacmar, C. (2007). Coping with abusive supervision: The neutralizing effects of ingratiation and positive affect on negative employee outcomes. Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (pp. 1–39). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2013). Conditional process modeling: Using structural equation modeling to examine contingent causal processes. In G. R. Hancock, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (2nd ed., pp. 219–266). IAP Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, N. A., & Blader, S. L. (2017). To give or not to give? Interactive effects of status and legitimacy on generosity. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 112(1), 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, J. P., Crum, A. J., Goyer, J. P., Marotta, M. E., & Akinola, M. (2018). Optimizing stress responses with reappraisal and mindset interventions: An integrated model. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 31(3), 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W., An, Y., Wang, L., & Zheng, C. (2021). Newcomers’ reaction to the abusive supervision toward peers during organizational socialization. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 128, 103586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokisaari, M., & Vuori, J. (2014). Joint effects of social networks and information giving on innovative performance after organizational entry. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampas, K., Pezirkianidis, C., & Stalikas, A. (2020). Psychometric properties of the Stress Mindset Measure (SMM) in a Greek sample. Psychology, 11(8), 1265–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellogg, K. C. (2012). Making the cut: Using status-based countertactics to block social movement implementation and microinstitutional change in surgery. Organization Science, 23(6), 1546–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. K., Moss, S., Quratulain, S., & Hameed, I. (2018). When and how subordinate performance leads to abusive supervision: A social dominance perspective. Journal of Management, 44(7), 2801–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korte, R., & Lin, S. (2013). Getting on board: Organizational socialization and the contribution of social capital. Human Relations, 66(3), 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (1990). Emotion, attention, and the startle reflex. Psychological Review, 97(3), 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1987). Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality, 1(3), 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H. W., Choi, J. N., & Kim, S. (2018). Does gender diversity help teams constructively manage status conflict? An evolutionary perspective of status conflict, team psychological safety, and team creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 144, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, W. E. K., & Simpson, D. D. (1992). Employee substance use and on-thejob behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(3), 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zeng, H., & Zhao, S. (2021). Research on the influence of mentoring system on protégés’ innovation performance: The role of psychological availability and proactive personality. Journal of Business Economics, 03, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Song, Y., Trainer, H., Carter, D., Zhou, L., Wang, Z., & Chiang, J. T.-J. (2023). Feeling negative or positive about fresh blood? Understanding veterans’ affective reactions toward newcomer entry in teams from an affective events perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(5), 728–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, J. C., & Thau, S. (2014). Falling from great (and not-so-great) heights: How initial status position influences performance after status loss. Academy of Management Journal, 57(1), 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauman, S., Zheng, C., & Basit, A. A. (2020). How despotic leadership jeopardizes employees’ performance: The roles of quality of work life and work withdrawal. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okimoto, T. G., & Wenzel, M. (2011). Third-party punishment and symbolic intragroup status. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(4), 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paullin, C. (2014). The aging workforce: Leveraging the talents of mature employees. SHRM Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, N. C., Doyle, S. P., Lount, R. B., & To, C. (2016). Cheating to get ahead or to avoid falling behind? The effect of potential negative versus positive status change on unethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 137, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, N. C., Yong, K., & Spataro, S. E. (2010). Holding your place: Reactions to the prospect of status gains and losses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(2), 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reh, S., Tröster, C., & Van Quaquebeke, N. (2018). Keeping (future) rivals down: Temporal social comparison predicts coworker social undermining via future status threat and envy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(4), 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C. L. (1982). Status in groups: The importance of motivations. American Sociological Review, 47(1), 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C. L., & Berger, J. (1986). Expectations, legitimation, and dominance behavior in task groups. American Sociological Review, 51(5), 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgeway, C. L., & Correll, S. J. (2006). Consensus and the creation of status beliefs: Social forces. Social Forces, 85(1), 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodell, J. B., & Judge, T. A. (2009). Can “good” stressors spark “bad” behaviors? The mediating role of emotions in links of challenge and hindrance stressors with citizenship and counterproductive behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1438–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F. L., Hunter, J. E., & Outerbridge, A. N. (1986). Impact of job experience and ability on job knowledge, work sample performance, and supervisory ratings of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. (2022). Is political skill always beneficial? Why and when politically skilled employees become targets of coworker social undermining: Organization science. Organization Science, 33(3), 1142–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J., Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Wu, Y., Liu, L. A., Guo, R., & Gu, J. (2024). How are newcomer proactive behaviors received by leaders and peers? A relational perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(2), 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L., & Duffy, M. K. (2016). A social-contextual view of envy in organizations: From both envier and envied perspectives. In R. H. Smith, U. Merlone, & M. K. Duffy (Eds.), Envy at work and in organizations (pp. 39–56). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L., Duffy, M. K., & Tepper, B. J. (2018). Consequences of downward envy: A model of self-esteem threat, abusive supervision, and supervisory leader self-improvement. Academy of Management Journal, 61(6), 2296–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G., Zhong, J., & Ozer, M. (2020). Status threat and ethical leadership: A power-dependence perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 161(3), 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N., Bai, B., & Zhu, J. (2023). Stress mindset, proactive coping behavior, and posttraumatic growth among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 15(3), 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Huang, X., & Xie, W. (2020). Does perceived overqualification inspire employee voice? Based on the lens of fairness heuristic. Management Review, 32(12), 192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J., Li, N., & Chi, W. (2022). Getting ahead or getting along? How motivational orientations forge newcomers’ cohort network structures, task assistance, and turnover. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(3), 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage | Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 127 | 47.74% | Tenure | 3–6 years | 169 | 63.53% |

| Female | 139 | 52.26% | 7–9 years | 45 | 16.92% | ||

| Age | 18–25 | 45 | 16.92% | over 10 years | 52 | 19.55% | |

| 26–35 | 138 | 51.88% | Position level | General staff | 113 | 42.48% | |

| 36–45 | 62 | 23.31% | Frontline manager | 97 | 36.47% | ||

| 46–55 | 17 | 6.39% | Department manager | 46 | 17.29% | ||

| >55 | 4 | 1.50% | Senior manager | 10 | 3.76% | ||

| Education level | Associate’s degree or below | 55 | 20.68% | Organization Type | Government agency/public institution | 42 | 15.79% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 161 | 60.53% | State-owned Enterprise | 49 | 18.42% | ||

| Master’s degree | 47 | 17.67% | Private Enterprise | 150 | 56.39% | ||

| Doctoral degree | 3 | 1.13% | Foreign-funded or joint venture enterprise | 25 | 9.40% |

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seven-factor model | 486.93 | 301 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Six-factor model 1 a | 788.07 | 307 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| Six-factor model 2 b | 879.20 | 309 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| Five-factor model c | 1180.69 | 314 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.10 | 0.14 |

| Four-factor model d | 1550.36 | 318 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.52 | 0.50 | - | ||||||||||||

| 2. Age | 1.24 | 0.86 | −0.06 | - | |||||||||||

| 3. Education level | 0.99 | 0.66 | 0.06 | −0.18 ** | - | ||||||||||

| 4. Tenure | 0.56 | 0.80 | −0.07 | 0.62 ** | −0.09 | - | |||||||||

| 5. Organization type | 1.59 | 0.87 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.23 ** | −0.13 * | - | ||||||||

| 6. Position level | 0.82 | 0.85 | −0.10 | 0.34 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.09 | - | |||||||

| 7. New Employees’ Job Performance | 3.16 | 0.94 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.14 * | −0.05 | −0.08 | 0.10 | (0.79) | ||||||

| 8. Incumbent Employees’ Perceived Status Threat | 2.17 | 0.85 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.11 | −0.08 | 0.10 | −0.14 * | 0.24 ** | (0.75) | |||||

| 9. Approach Coping | 3.67 | 0.91 | −0.06 | −0.09 | 0.12 * | −0.10 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.19 ** | 0.48 ** | (0.78) | ||||

| 10. Avoidance Coping | 2.41 | 0.75 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.09 | −0.01 | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.15 * | −0.02 | (0.61) | |||

| 11. Work Engagement | 3.61 | 0.79 | −0.01 | 0.16 * | 0.03 | 0.16 ** | 0.07 | 0.20 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.43 ** | −0.13 * | (0.74) | ||

| 12. Work Withdrawal | 1.87 | 0.56 | −0.05 | −0.16 ** | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.09 | −0.23 ** | −0.02 | 0.20 ** | −0.02 | 0.35 ** | −0.37 ** | (0.62) | |

| 13. Stress Mindset | 3.87 | 0.67 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.16 * | 0.19 ** | −0.08 | 0.18 ** | −0.45 ** | 0.46 ** | −0.56 ** | (0.71) |

| Perceived Status Threat | Work Engagement | Work Withdrawal | Approach Coping | Avoidance Coping | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | M11 | M12 | M13 | M14 | |

| Gender | −0.12 | −0.14 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.11 | −0.16 | −0.10 | −0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Age | −0.02 | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.09 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Education level | −0.09 | −0.13 | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.22 * | 0.26 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.16 * | 0.17 * | 0.17 ** |

| Tenure | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.05 |

| Organization type | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.09 * | 0.08 | 0.08 * | 0.15 * | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| Position level | −0.13 | −0.16 * | 0.13 * | 0.17 ** | 0.16 * | −0.16 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.12 ** | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.12 | −0.04 | −0.04 |

| New Employees’ Job Performance | 0.26 *** | |||||||||||||

| Perceived Status Threat | 0.28 *** | 0.10 | 0.11 ** | 0.08 * | −0.16 | 0.54 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.11 * | 0.13 ** | |||||

| Approach Coping | 0.34 *** | |||||||||||||

| Avoidance Coping | 0.24 *** | |||||||||||||

| Stress Mindset | 0.30 *** | 0.30 *** | −0.48 *** | −0.46 *** | ||||||||||

| Stress Mindset × Perceived Status Threat | −0.07 | −0.20 ** | ||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.27 |

| ΔR2 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| Dependent Variable | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LL 95% CI | Boot UL 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work Engagement | Direct effect | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.002 | 0.190 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.025 | 0.137 | |

| JP–ST–WE | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.011 | 0.049 | |

| JP–AP–WE | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.024 | 0.057 | |

| JP–ST–AP–WE | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.021 | 0.075 | |

| Work Withdrawal | Direct effect | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.091 | 0.047 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.002 | 0.067 | |

| JP–ST–WW | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.048 | |

| JP–AV–WW | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.024 | 0.028 | |

| JP–ST–AV–WW | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, Y.; Hu, K.; Zhang, W.; Yan, Y. All Eyes on the New, but Who Hears the Old? The Impact of Incumbent Employees’ Perceived Status Threat on Work Behavior. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111550

Ji Y, Hu K, Zhang W, Yan Y. All Eyes on the New, but Who Hears the Old? The Impact of Incumbent Employees’ Perceived Status Threat on Work Behavior. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111550

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Yanshu, Ke Hu, Wen Zhang, and Yuanyun Yan. 2025. "All Eyes on the New, but Who Hears the Old? The Impact of Incumbent Employees’ Perceived Status Threat on Work Behavior" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111550

APA StyleJi, Y., Hu, K., Zhang, W., & Yan, Y. (2025). All Eyes on the New, but Who Hears the Old? The Impact of Incumbent Employees’ Perceived Status Threat on Work Behavior. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111550