From Gender Threat to Farsightedness: How Women’s Perceived Intergroup Threat Shapes Their Long-Term Orientation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study 1

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Measures

2.2. Results

2.3. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Procedure and Materials

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Manipulation Check

3.2.2. Effect of Gender Intergroup Threat on Intertemporal Decision-Making

3.2.3. Mediating Role of Cognitive Appraisal

3.3. Discussion

4. Study 3

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Procedure and Materials

- Realistic Threat Condition: Participants read a passage describing real-life gender inequalities and completed three tasks: (1) rated their level of concern about experiencing such situations on a 7-point scale; (2) described, in writing, similar events they had heard of or experienced; and (3) imagined and described a similar future scenario they might face (at least 100 words).

- Symbolic Threat Condition: Procedures mirrored those of the realistic threat condition; however, the materials and reflections focused on gender bias (e.g., devaluation of women’s achievements or stereotypes regarding women’s roles).

- Control Condition: Participants recalled memorable childhood events and imagined possible future lifestyle changes.

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Manipulation Check

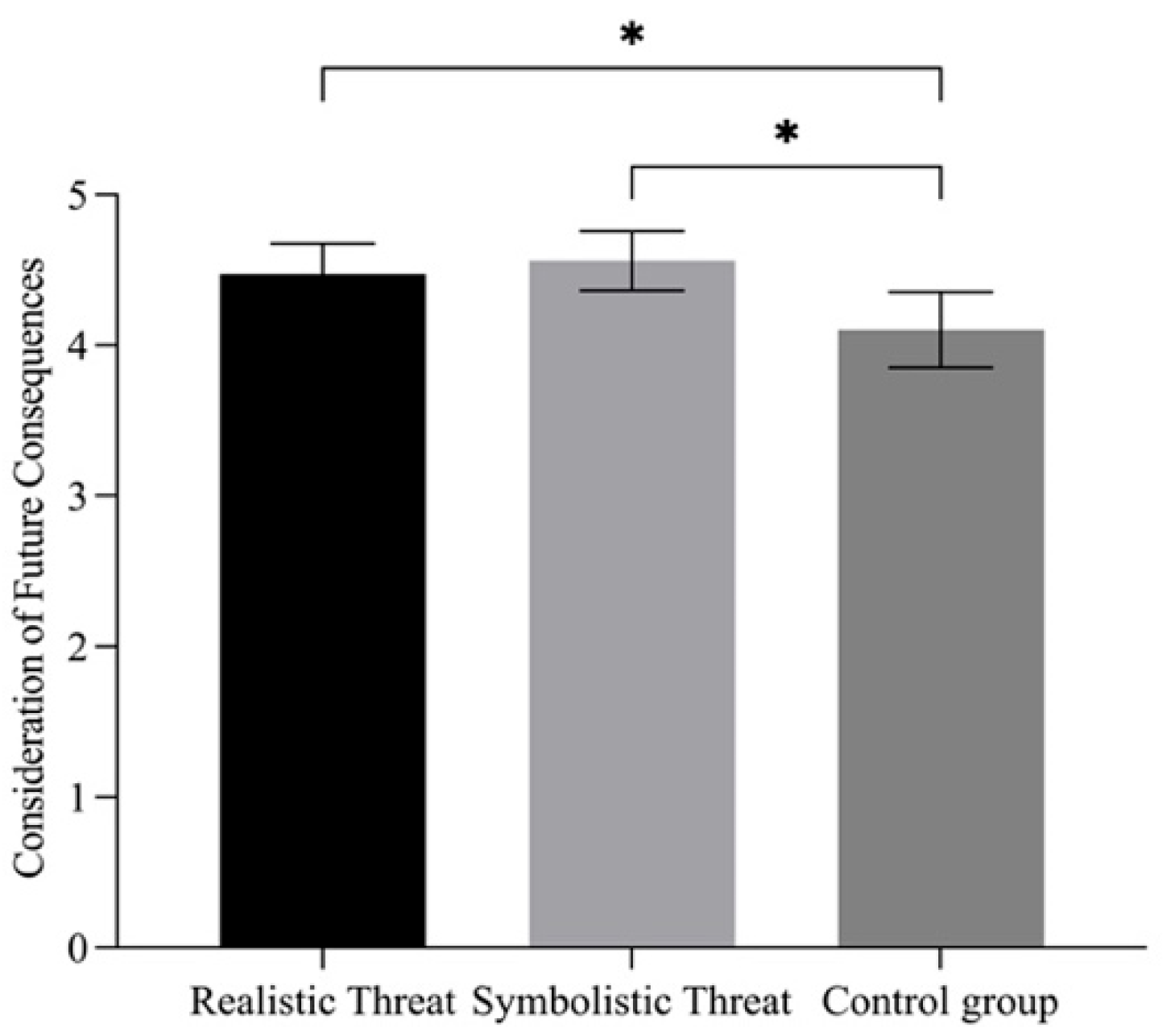

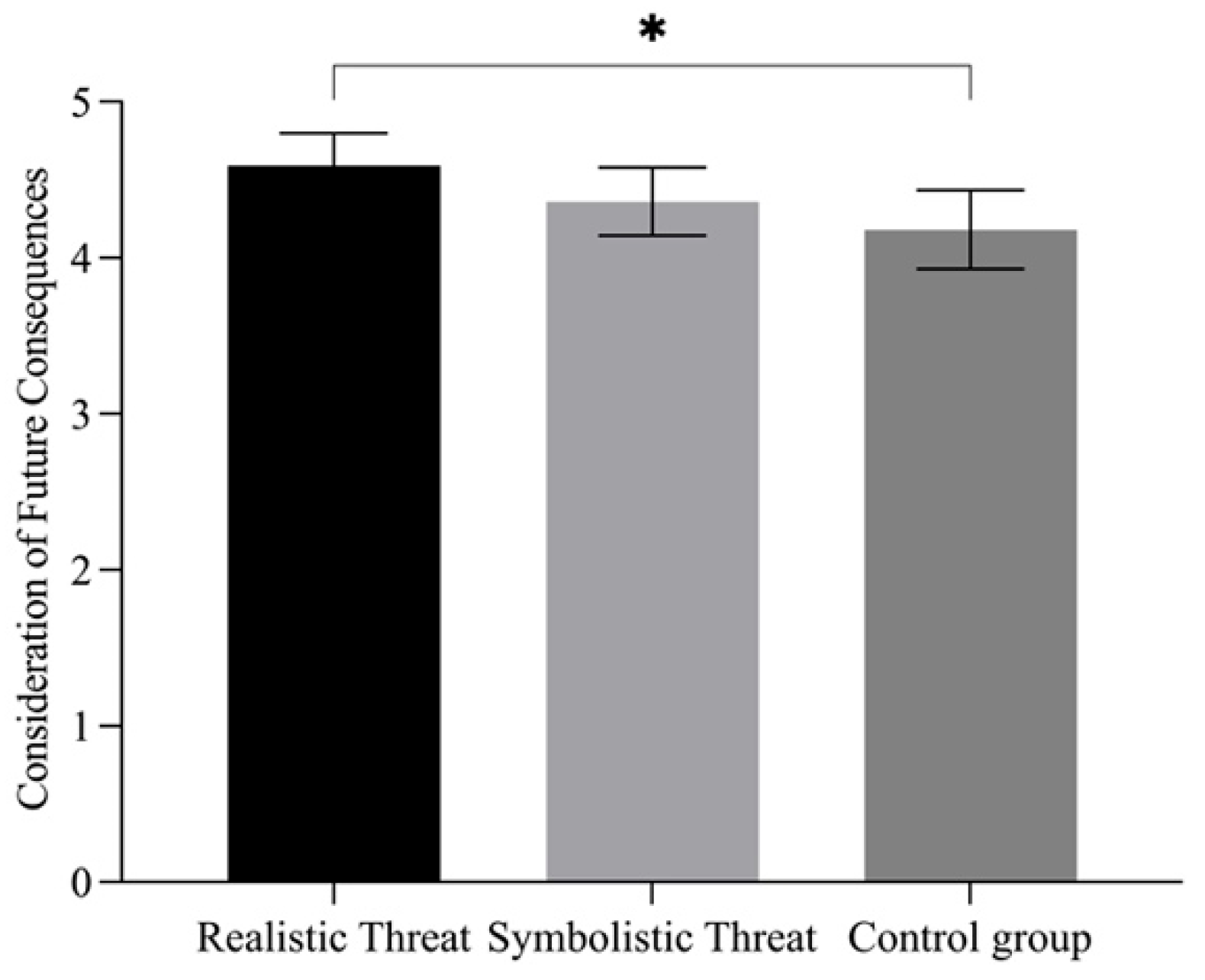

4.2.2. Effect of Gender Intergroup Threat on Intertemporal Decision-Making

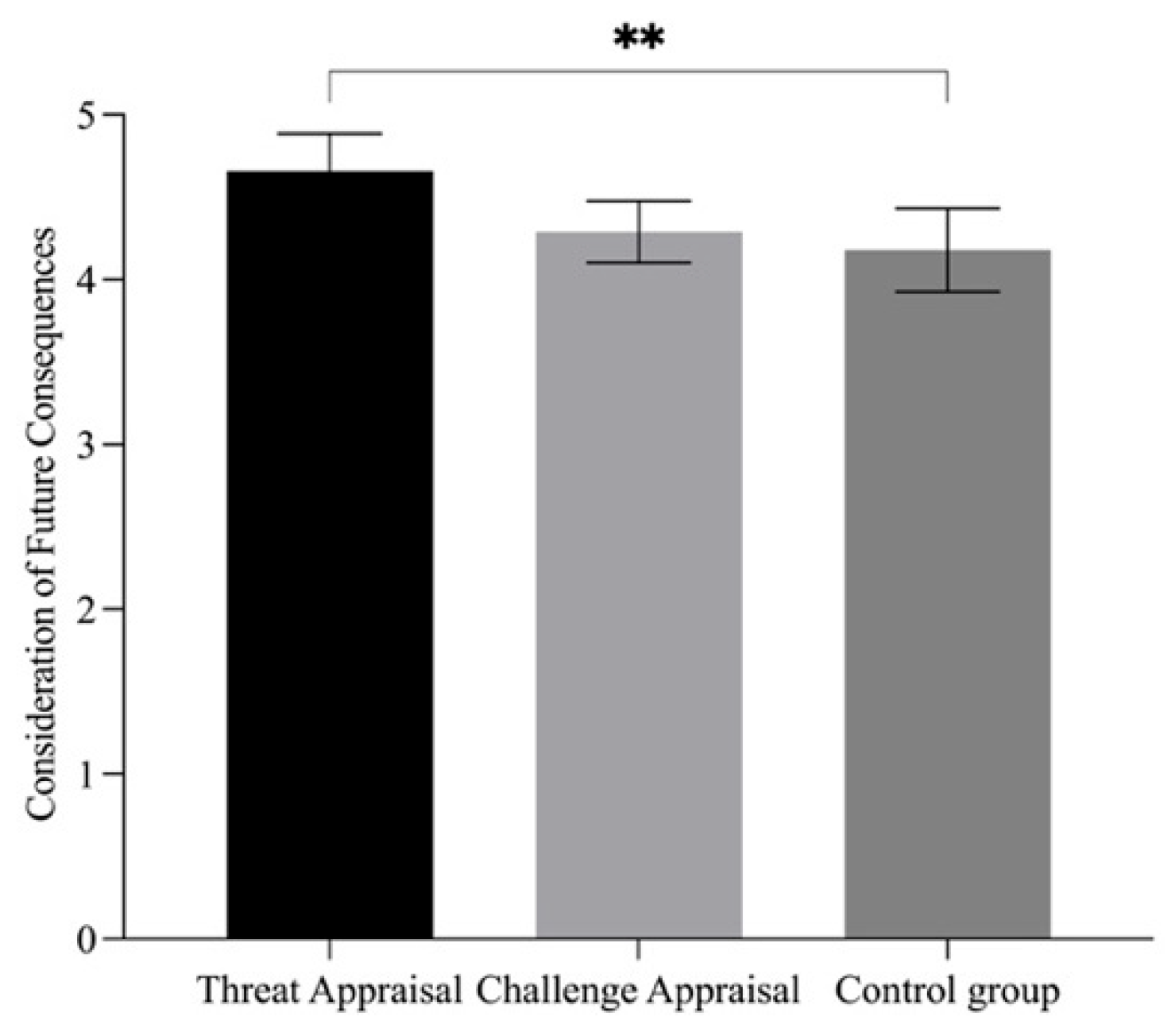

4.2.3. Effect of Cognitive Appraisal Style on Intertemporal Decision-Making

4.3. Discussion

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcover, C.-M., Rodríguez, F., Pastor, Y., Thomas, H., Rey, M., & Del Barrio, J. L. (2020). Group membership and social and personal identities as psychosocial coping resources to psychological consequences of the COVID-19 confinement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alter, A. L., Aronson, J., Darley, J. M., Rodriguez, C., & Ruble, D. N. (2010). Rising to the threat: Reducing stereotype threat by reframing the threat as a challenge. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atherton, O. E., Grijalva, E., Roberts, B. W., & Robins, R. W. (2021). Stability and change in personality traits and major life outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(5), 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennamate, S., & Bouazzaoui, A. E. (2023). Social identity, social influence, and response to potentially stressful situations: Support for the self-categorization theory. Journal of Knowledge Learning and Science Technology, 2(3), 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berjot, S., Roland-Levy, C., & Girault-Lidvan, N. (2011). Cognitive appraisals of stereotype threat. Psychological Reports, 108(2), 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blascovich, J., & Mendes, W. B. (2000). Challenge and threat appraisals: The role of affective cues. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Feeling and thinking: The role of affect in social cognition (pp. 59–82). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blascovich, J., Seery, M. D., Mugridge, C. A., Norris, R. K., & Weisbuch, M. (2004). Predicting athletic performance from cardiovascular indices of challenge and threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1996). The biopsychosocial model of arousal regulation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 28, pp. 1–51). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Breakwell, G. M. (2021). Identity resilience: Its origins in identity processes and its role in coping with threat. Contemporary Social Science, 16(5), 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Luo, L., Wu, X., Chen, Y., & Zhao, Y. (2021). Are the lower class really unhappy? Social class and subjective well-being in Chinese adolescents: Moderating role of sense of control and mediating role of self-esteem. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(2), 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichocka, A., Golec De Zavala, A., Kofta, M., & Rozum, J. (2013). Threats to feminist identity and reactions to gender discrimination. Sex Roles, 68(9–10), 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Diekman, A. B., Clark, E. K., Johnston, A. M., Brown, E. R., & Steinberg, M. (2011). Malleability in communal goals and beliefs influences attraction to stem careers: Evidence for a goal congruity perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(5), 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domen, I., Scheepers, D., Derks, B., & Van Veelen, R. (2022). It’s a man’s world; right? How women’s opinions about gender inequality affect physiological responses in men. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(3), 703–726. [Google Scholar]

- Du, T. Y., Hu, X. Y., Yang, J., Li, L. Y., & Wang, T. T. (2022). Low socioeconomic status and intertemporal choice: The mechanism of “psychological-shift” from the perspective of threat. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(8), 1894–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A. R., Tokar, D. M., Mergl, M. M., Good, G. E., Hill, M. S., & Blum, S. A. (2000). Assessing women’s feminist identity development: Studies of convergent, discriminant, and structural validity. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24(1), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisseha, S., Sen, G., Ghebreyesus, T. A., Byanyima, W., Diniz, D., Fore, H. H., Kanem, N., Karlsson, U., Khosla, R., Laski, L., Mired, D., Mlambo-Ngcuka, P., Mofokeng, T., Gupta, G. R., Steiner, A., Remme, M., & Allotey, P. (2021). COVID-19: The turning point for gender equality. Lancet, 398(10299), 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillman, J. C., Turner, M. J., & Slater, M. J. (2023). The role of social support and social identification on challenge and threat cognitive appraisals, perceived stress, and life satisfaction in workplace employees. PLoS ONE, 18(7), e0288563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, L., & Myerson, J. (2004). A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Bulletin, 130(5), 769–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L. L., Liang, J. P., & Yu, Y. (2024). Inspiration and consumer patience in intertemporal choice: A moderated mediation model of meaning in life and regulatory focus. Journal of Business Research, 180, 114733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, R. A., Hunter, M. S., & Jackson, S. E. (2024). The relationship between gender discrimination and wellbeing in middle-aged and older women. PLoS ONE, 19(3), e0299381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, R. A., Steptoe, A., & Jackson, S. E. (2019). Sex discrimination and mental health in women: A prospective analysis. Health Psychology, 38(11), 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins-Doyle, A., Petterson, A. L., Leach, S., Zibell, H., Chobthamkit, P., Binti Abdul Rahim, S., Blake, J., Bosco, C., Cherrie-Rees, K., Beadle, A., Cock, V., Greer, H., Jankowska, A., Macdonald, K., Scott English, A., Wai Lan Yeung, V., Asano, R., Beattie, P., Bernardo, A. B. I., … Sutton, R. M. (2024). The misandry myth: An inaccurate stereotype about feminists’ attitudes toward men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 48(1), 8–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, J., Branscombe, N. R., Haslam, S. A., Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., Jones, J. M., Cui, L., Dingle, G., Liu, J., Murphy, S., Thai, A., Walter, Z., & Zhang, A. (2015). Having a lot of a good thing: Multiple important group memberships as a source of self-esteem. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0124609. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y. P., Jiang, C. M., Hu, T. Y., & Sun, H. Y. (2022). Effects of emotion on intertemporal decision-making: Explanation from the single dimension priority model. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 54(2), 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joireman, J., Balliet, D., Sprott, D., Spangenberg, E., & Schultz, J. (2008). Consideration of future consequences, ego-depletion, and self-control: Support for distinguishing between CFC-Immediate and CFC-Future sub-scales. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(1), 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A., Turner, R. N., & Latu, I. M. (2022). Resistance towards increasing gender diversity in masculine domains: The role of intergroup threat. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(3), NP24–NP53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, K. B., Van Breen, J. A., Barreto, M., & Kaiser, C. R. (2021). When is women’s benevolent sexism associated with support for other women’s agentic responses to gender-based threat? British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(3), 786–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, B. A., Amlung, M., Reed, D. D., Jarmolowicz, D. P., McKerchar, T. L., & Lemley, S. M. (2016). Automating scoring of delay discounting for the 21- and 27-item monetary choice questionnaires. The Behavior Analyst, 39(2), 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, K. N., Petry, N. M., & Bickel, W. K. (1999). Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 128(1), 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudenburg, N., Kannegieter, A., Postmes, T., & Kashima, Y. (2021). The subtle spreading of sexist norms. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(8), 1467–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt, K., Zhu, L., Klotz, A., & Kouchaki, M. (2022). Fragile or robust? Differential effects of gender threats in the workplace among men and women. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 168, 104112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. L., & Zhao, Y. F. (2015). Effect of cognitive appraisal of realistic intergroup threat on executive function. Journal of Southwest University (Natural Science Edition), 37(12), 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective selfesteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C., Xiao, Z., Sun, Y., Zhang, R., Feng, T., Turel, O., & He, Q. (2023). Gender-specific resting-state rDMPFC-centric functional connectivity underpinnings of intertemporal choice. Cerebral Cortex, 33(18), 10066–10075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesza, M. (2019). Stress and delay discounting: The mediating role of difficulties in emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 144, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. I. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Off, G., Charron, N., & Alexander, A. (2022). Who perceives women’s rights as threatening to men and boys? Explaining modern sexism among young men in Europe. Frontiers in Political Science, 4, 909811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, G., & Nettle, D. (2017). The behavioural constellation of deprivation: Causes and consequences. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40, e314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K., Ryan, M. K., & Haslam, S. A. (2013). Women’s occupational motivation: The impact of being a woman in a man’s world. In S. Vinnicombe, R. J. Burke, S. Blake-Beard, & L. L. Moore (Eds.), Handbook of research on promoting women’s careers (pp. 162–177). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, S., Maylor, E. A., Stewart, N., & Chater, N. (2009). Associations between a one-shot delay discounting measure and age, income, education and real-world impulsive behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, K., Sosa, N., & Osborn, H. (2018). An experimental approach to intergroup threat theory: Manipulations, moderators, and consequences of realistic vs. symbolic threat. European Review of Social Psychology, 29(1), 212–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Rodriguez, A., Larsen, G., & Dasgupta, N. (2022). Changing public opinion about gender activates group threat and opposition to feminist social movements among men. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 25(3), 811–829. [Google Scholar]

- Rutchick, A. M., Hamilton, D. L., & Sackrin, S. M. (2008). Group status, perceptions of threat, and support for social inequality. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(3), 831–849. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M. K., & Morgenroth, T. (2024). Why we should stop trying to fix women: How context shapes and constrains women’s career trajectories. Annual Review of Psychology, 75(1), 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarter, E., Hegarty, P., & Casini, A. (2024). Gender-critical or gender-inclusive?: Radical feminism is associated with positive attitudes toward trans* people and their rights. Sex Roles, 90(10), 1301–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepers, D., & Knight, E. L. (2020). Neuroendocrine and cardiovascular responses to shifting status. Current Opinion in Psychology, 33, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmader, T. (2023). Gender inclusion and fit in STEM. Annual Review of Psychology, 74, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Postmes, T., & Garcia, A. (2014). The consequences of perceived discrimination for psychological well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 921–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, E., Tully, S. M., & Wang, X. (2023). Scarcity and intertemporal choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Attitudes and Social Cognition, 125(5), 1036–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehy-Skeffington, J. (2020). The effects of low socioeconomic status on decision-making processes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 33, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, L., Jiryis, T., & Admon, R. (2021). Now or later? Stress-induced increase and decrease in choice impulsivity are both associated with elevated affective and endocrine responses. Brain Sciences, 11(9), 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V., Schiebener, J., Müller, S. M., Liebherr, M., Brand, M., & Buelow, M. T. (2020). Country and sex differences in decision making under uncertainty and risk. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L., Graham, S., O’brien, L., Woolard, J., Cauffman, E., & Banich, M. (2009). Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Development, 80(1), 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, C. W., Stephan, W. G., Demitrakis, K. M., Yamada, A. M., & Clason, D. L. (2000). Women’s attitudes toward men: An integrated threat theory approach. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24(1), 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., & Morrison, K. R. (2009). Intergroup threat theory. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (pp. 43–59). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strathman, A., Gleicher, F., Boninger, D. S., & Edwards, C. S. (1994). The consideration of future consequences: Weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(4), 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stürmer, S., & Simon, B. (2004). The role of collective identification in social movement participation: A panel study in the context of the German gay movement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(3), 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R., Yuki, M., Talhelm, T., Schug, J., Kito, M., Ayanian, A. H., Becker, J. C., Becker, M., Chiu, C., Choi, H.-S., Ferreira, C. M., Fülöp, M., Gul, P., Houghton-Illera, A. M., Joasoo, M., Jong, J., Kavanagh, C. M., Khutkyy, D., Manzi, C., … Visserman, M. L. (2018). Relational mobility predicts social behaviors in 39 countries and is tied to historical farming and threat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(29), 7521–7526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaka, J., Blascovich, J., Kibler, J., & Ernst, J. M. (1997). Cognitive and physiological antecedents of threat and challenge appraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M. J., Evans, A. L., Fortune, G., & Chadha, N. J. (2024). “I must make the grade!”: The role of cognitive appraisals, irrational beliefs, exam anxiety, and affect, in the academic self-concept of undergraduate students. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 37(6), 721–744. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). (2025). The sustainable development goals report 2025 (July 2025). UN DESA. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- UN Women. (2023). Progress on the sustainable development goals: The gender snapshot 2023. UN Women. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laar, C., Meeussen, L., Veldman, J., Van Grootel, S., Sterk, N., & Jacobs, C. (2019). Coping with stigma in the workplace: Understanding the role of threat regulation, supportive factors, and potential hidden costs. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vigod, S. N., & Rochon, P. A. (2020). The impact of gender discrimination on a woman’s mental health. EClinicalMedicine, 20, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva-Moya, L., & Exposito, F. (2021). Gender differences in decision-making: The effects of gender stereotype threat moderated by sensitivity to punishment and fear of negative evaluation. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 34(5), 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonasch, A. J., & Sjåstad, H. (2021). Future-orientation (as trait and state) promotes reputation-protective choice in moral dilemmas. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(3), 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. P., & He, J. M. (2020). Effects of episodic foresight on intertemporal decision-making. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51(1), 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. P., & Hugenberg, K. (2010). When under threat, we all look the same: Distinctiveness threat induces ingroup homogeneity in face memory. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(6), 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2025). Global gender gap report 2025. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-gender-gap-report-2025/in-full/benchmarking-gender-gaps-2025/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Xu, L., Chen, Q., Cui, N., & Lu, K. L. (2019). Enjoy the present or wait for the future? Effects of individuals’ view of time on intertemporal choice. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51(3), 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L., Li, A. M., Zhang, L., & Liang, Z. Y. (2019). Similarity in processes of risky choice and intertemporal choice: The case of certainty effect and immediacy effect. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 52(1), 38–54. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 20.96 | 2.54 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Gender Identity | 5.43 | 0.82 | 0.03 | 1 | |||||

| 3. Realistic Threat Perception | 5.04 | 1.07 | −0.12 * | 0.18 ** | 1 | ||||

| 4. Symbolic Threat Perception | 5.25 | 0.81 | −0.06 | 0.12 * | 0.68 *** | 1 | |||

| 5. Delay Discounting Rate (k0) | −4.18 | 1.84 | 0.14 * | −0.02 | −0.18 ** | −0.06 | 1 | ||

| 6. Subjective Social Class | 4.74 | 1.48 | 0.22 ** | −0.03 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.18 ** | 1 | |

| 7. Objective Social Class | 3.99 | 1.39 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.31 *** | 1 |

| Model | Predictor | B (SE) | β | t | p | R2 | ∆R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.10 | 1.71 | 0.089 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 6.25 |

| Subjective social class | 0.20 (0.08) | 0.16 | 2.65 | 0.009 | ||||

| 2 | Age | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.08 | 1.37 | 0.171 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 5.44 |

| Subjective social class | 0.19 (0.07) | 0.15 | 2.58 | 0.010 | ||||

| Realistic threat perception | −0.40 (0.14) | −0.23 | −2.91 | 0.004 | ||||

| Symbolic threat perception | 0.27 (0.18) | 0.12 | 1.49 | 0.138 |

| Effect | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Realistic Threat → Delay Discounting Rate | 0.718 | 0.36 | [−0.01, 1.44] |

| Realistic Threat → Cognitive Appraisal → Delay Discounting Rate | −0.285 * | 0.13 | [−0.56, −0.05] |

| Symbolic Threat → Delay Discounting Rate | 0.779 * | 0.34 | [0.11, 1.45] |

| Symbolic Threat → Cognitive Appraisal → Delay Discounting Rate | −0.022 | 0.04 | [−0.10, 0.07] |

| Realistic Threat → Consideration of Future Consequences | 0.255 | 0.16 | [−0.07, 0.58] |

| Realistic Threat → Cognitive Appraisal → Consideration of Future Consequences | 0.114 * | 0.07 | [0.14, 0.75] |

| Symbolic Threat → Consideration of Future Consequences | 0.447 * | 0.15 | [0.01, 0.25] |

| Symbolic Threat → Cognitive Appraisal → Consideration of Future Consequences | 0.009 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, S. From Gender Threat to Farsightedness: How Women’s Perceived Intergroup Threat Shapes Their Long-Term Orientation. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1542. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111542

Shi Y, Zhao Y, Ma X, Chen S. From Gender Threat to Farsightedness: How Women’s Perceived Intergroup Threat Shapes Their Long-Term Orientation. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1542. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111542

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Yongheng, Yufang Zhao, Xingyang Ma, and Shasha Chen. 2025. "From Gender Threat to Farsightedness: How Women’s Perceived Intergroup Threat Shapes Their Long-Term Orientation" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1542. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111542

APA StyleShi, Y., Zhao, Y., Ma, X., & Chen, S. (2025). From Gender Threat to Farsightedness: How Women’s Perceived Intergroup Threat Shapes Their Long-Term Orientation. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1542. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111542