At the Intersection of Transnationalism, Identity, and Conocimiento: An Autoethnography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Situating Transnationalism and Education

2.2. Transnational Children and Youth

2.3. Transnationals and Identity

2.4. Transnational Knowledge

2.5. Transnationalism and Education: A Comparative Stance

3. Methodology

3.1. Autoethnography

3.2. [Re]Engaging in Transitions, [Re]Creating Networks, and [Re]Developing Attachments: My Story

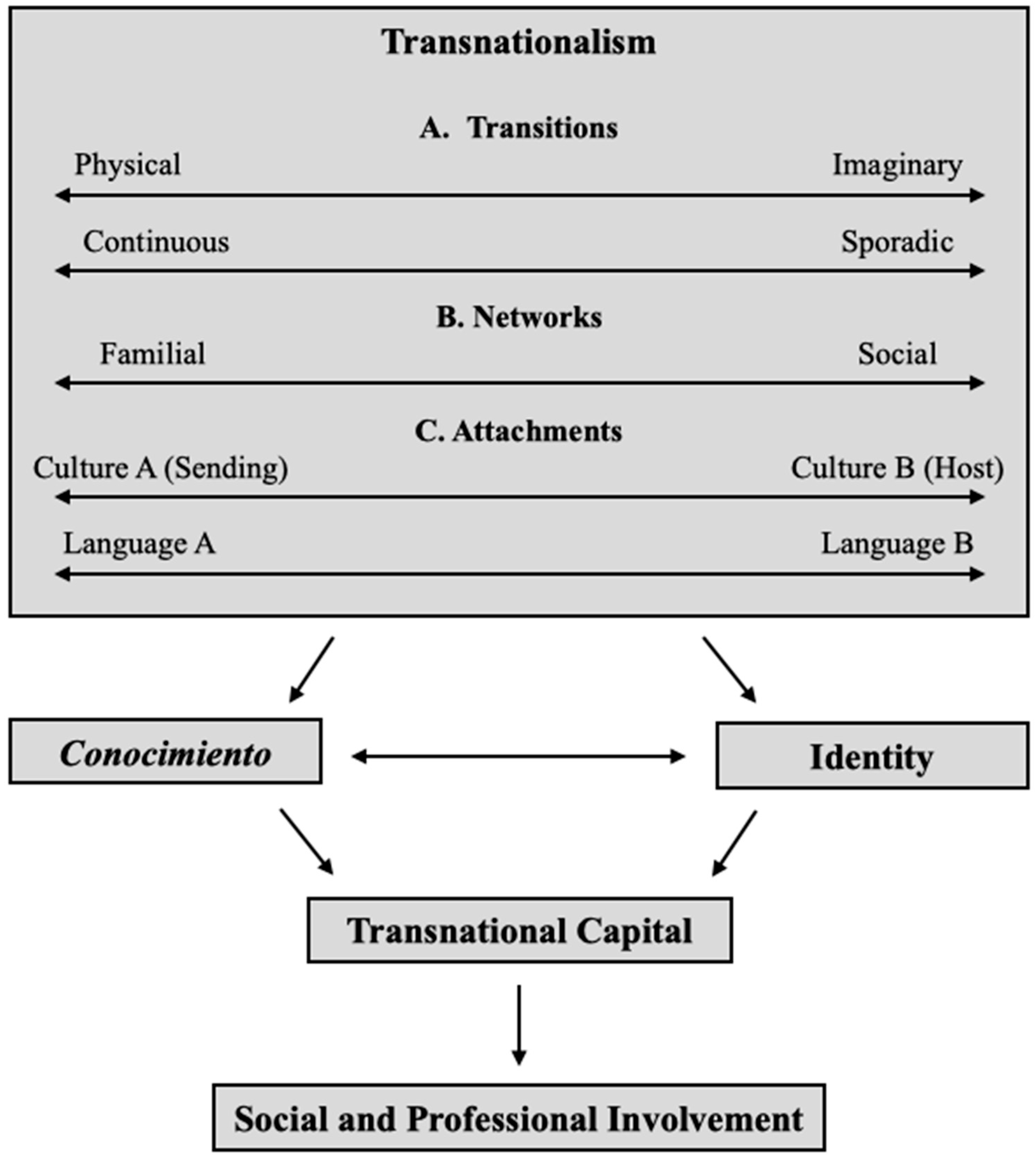

3.3. At the Crossroads of Conocimiento, Identity, and Transnational Capital

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, L. (2006). Analytic autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35, 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzaldúa, G. E. (1987). Borderlands/La frontera: The new Mestiza. Aunt Lute. [Google Scholar]

- Avilés, A. G., & Mora Pablo, I. (2014). Migrants children of return in central Mexico: Exploring their identity. Sologismo, 1(14), 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Basch, L., Glick Schiller, N., & Szanton Blanc, C. (1994). Nations unbound: Transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments and deterritorialized nation-states. Gordon and Breach Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Besserer, F. (2004). Topografías transnacionales: Hacia una geografía de la vida transnacional. Plaza y Valdés. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, D. A. (2012). Intimate migrations: Gender, family and illegality among transnational Mexicans. New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brittain, C. (2002). Transnational messages: Experiences of Chinese and Mexican immigrants in American schools. LFB Scholarly Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Brittain, C. (2009). Transnational messages: What teachers can learn from understanding students’ lives in transnational social spaces. The High School Journal, 92(4), 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, E. R., Whiting, E. F., Jensen, B., Savage, V., Baker, A., & Holdway, E. (2020). “Estamos aquí pero no soy de aquí”: American Mexican youth, belonging and schooling in rural, central Mexico. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 52(2), 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2012). Teacher development in a global profession: An autoethnography. TESOL Quarterly, 46(2), 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capstick, T. (2021). Language and migration. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Casinader, N. (2017). Transnationalism, education and empowerment: The latent legacies of empire. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H. (2008). Autoethnography as method. Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, M. S. (2015a). ‘A ondi queras’: Ranchero identity construction by U.S. born Mexicans on Facebook. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 19(5), 688–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, M. S. (2015b). Mexicanness and social order in digital spaces: Contention among members of a multigenerational transnational network. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 37(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, M. S. (2016). Maintaining transnationalism: The role of digital communication among US-Born Mexicans. In J. O. García, & N. Baca Tavira (Eds.), Continuidades y cambios en las migraciones de México a Estados Unidos (pp. 353–376). Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, M. S., Trejo Guzmán, N. P., & Mora-Pablo, I. (2017). “You know English so why don’t you teach?” Language ideologies and returnees becoming English language teachers in Mexico. International Multilingual Research Journal, 12, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton-Lilly, C., Kim, J., Quast, E., Tran, S., & Shedrow, S. (2019). The emergence of transnational awareness among children in immigrant families. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 19(1), 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez Román, N. A., & Hamann, E. T. (2014). College dreams a la Mexicana… agency and strategy among American-Mexican transnational students. Latino Studies, 12(2), 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crisp, G., Taggart, A., & Nora, A. (2015). Undergraduate Latina/o students: A systematic review of research identifying factors contributing to academic success outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 85(2), 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Piedra, M. T. (2011). Tanto necesitamos de aquí como necesitamos de allá: Leer juntas among Mexican transnational mothers and daughters. Language and Education, 25(1), 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Piedra, M. T., & Araujo, B. E. (2012). Literacies crossing borders: Transfronterizo literacy practices of students in a dual language program on the USA–Mexico border. Language and Intercultural Communication, 12(3), 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. K. (2014). Interpretive autoethnography (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Despagne, C. (2018). Language is what makes everything easier: The awareness of semiotic resources of Mexican transnational students in Mexican schools. International Multilingual Research Journal, 13(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despagne, C., & Jacobo Suárez, M. (2016). Desafíos actuales de la escuela monolítica mexicana: El caso de los alumnos migrantes transnacionales. Sinéctica, 47, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Despagne, C., & Jacobo Suárez, M. (2019). The adaptation path of transnational students in Mexico: Linguistic and identity challenges in Mexican schools. Latino Studies, 17, 428–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despagne, C., & Manzano-Munguía, M. C. (2020). Youth return migration (US–Mexico): Students’ citizenship in Mexican schools. Children and Youth Services Review, 110, 104652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, L. D. (2009). “Allá en Guatemala”: Transnationalism, language, and identity of a Pentecostal Guatemalan-American young woman. The High School Journal, 92(4), 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C. (2009). Revision: Autoethnographic reflections on life and work. Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Espino, M. M. (2020). “I’m the one who pieces back together what was broken”: Uncovering mestiza consciousness in Latina-identified first generation college student narratives of stress and coping in higher education. Journal of Women and Gender in Higher Education, 13(2), 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espíritu, Y. L., & Tran, T. (2002). “Viet Nam, Nuoc Toi” (“Vietnam, My Country”): Vietnamese Americans and transnationalism. In P. Levitt, & M. Waters (Eds.), The changing face of home: The transnational lives of the second generation (pp. 367–398). Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Esquinca, A., Araujo, B., & de la Piedra, M. T. (2014). Meaning making and translanguaging in a two-way dual-language program on the U.S.–Mexico border. Bilingual Research Journal, 37, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J. (2006). Reframing Mexican migration as a multiethnic process. Latino Studies, 4, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O., & Kleifgen, A. (2018). Educating emergent bilinguals: Policies, programs, and practices for English learners (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., Kleifgen, J. A., & Falchi, L. (2008). From English language learners to emergent bilinguals (Equity Matters: Research Review No. 1). Teachers College, Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Solorza, C. R. (2020). Academic language and the minoritization of U.S. bilingual Latinx students. Language and Education, 35(6), 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gándara, P. (2016). Policy report-Informe: The students we share-los estudiantes que compartimos. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 32(2), 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gándara, P., & Jensen, B. (Eds.). (2021). The students we share: Preparing U.S. and Mexican educators for our transnational future. State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glick Schiller, N., Basch, L., & Blanc-Szanton, C. (1992). Transnationalism: A new analytic framework for understanding migration. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 645(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, G. (1997). Culture, language, and the Americanization of Mexican children. In A. Darder, R. Torres, & H. Gutiérrez (Eds.), Latinos and education: A critical reader (pp. 158–173). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Grillo, R. (2007). Betwixt and between: Trajectories and projects of transmigration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33(2), 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnizo, L. E. (1996). Transnationalism from below: Social transformation and the mirage of return migration among Dominican transmigrants [Unpublished manuscript]. University of California, Davis.

- Guarnizo, L. E. (1999). On the political participation of transnational migrants: Old practices and new trends. In J. Mollenkopf, & G. Gerstle (Eds.), Immigrants, civic culture, and modes of political incorporation. Sage and Social Science Research Council. [Google Scholar]

- Guarnizo, L. E., Portes, A., & Haller, W. (2003). Assimilation and transnationalism: Determinants of transnational political action among contemporary migrants. American Journal of Sociology, 108(6), 1211–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnizo, L. E., & Smith, M. P. (1998). The locations of transnationalism. In M. P. Smith, & L. E. Guarnizo (Eds.), Transnationalism from below (pp. 3–34). Transaction. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, E. T., Wortham, S., & Murillo, E. G. (2001). Education and policy in the new Latino diaspora. In S. Wortham, E. Murillo Jr., & E. T. Hamann (Eds.), Education in the new Latino diaspora: Policy and politics of identity (pp. 1–16). Ablex Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, E. T., & Zúñiga, V. (2011a). Schooling and the everyday ruptures of transnational children encounter in the United States and Mexico. In C. Coe, R. R. Reynolds, D. A. Boehm, J. M. Hess, & H. Rae-Espinoza (Eds.), Everyday ruptures: Children, youth, and migration in global perspective (pp. 141–160). VUP. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, E. T., & Zúñiga, V. (2011b). Schooling, national affinity(ies), and transnational students in Mexico. In S. Vandeyar (Ed.), Hyphenated selves: Immigrant identities within education contexts (pp. 1–18). UNISA. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, E. T., Zúñiga, V., & García, J. S. (2008). From Nuevo León to the USA and back again: Transnational students in Mexico. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 6(1), 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, E. T., Zúñiga, V., & Sánchez, J. (2006). Pensando en Cynthia y su hermana: Educational implications of United States–Mexico transnationalism for children. Journal of Latinos and Education, 5(4), 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, E. T., Zúñiga, V., & Sánchez García, J. (Eds.). (2022). Lo que conviene que los maestros mexicanos conozcan sobre la educación básica en Estados Unidos [What Mexican teachers need to know about ‘educación básica’ in the United States]. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst, P., & Thompson, G. (1999). Globalization in question (2nd ed.). Caldwell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, R. J. (1998). Globalization and the nation-state. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hopewell, S., & Escamilla, K. (2014). Biliteracy development in immersion contexts. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 2(2), 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, N. H. (2007). Biliteracy, transnationalism, multimodality, and identity: Trajectories across time and space. Linguistics and Education, 18, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, S., Ramirez, J., & Cho, K. (2018). The current Latinx/a/o landscape of enrollment and success in higher education. In A. E. Batista, S. M. Collado, & D. Perez II (Eds.), Latinx/a/os in higher education: Exploring identity, pathways, and success. NASPA. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobo, M., & Despagne, C. (2022). Young return migrants: Building alternative notions of citizenship in Mexico. Estudios Sociológicos, 40(119), 487–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo, M., & Jensen, B. (2018). Schooling for US-citizen students in Mexico. Civil rights project, UCLA. Available online: https://www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/immigration-immigrant-students/when-families-are-deported-schooling-for-us-citizen-students-in-mexico/Schooling-for-US-Citizens_Jacobo-and-Jensen_June19.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Jacobo-Suárez, M. (2017). De regreso a “casa” y sin apostilla: Estudiantes mexicoamericanos en México. Sinéctica, 48, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobo Suárez, M. L. (2023). Being a professional in Mexico: Experiences of return migrants and Mexican-American immigrants in higher education. Diarios del Terruño, 16(2), 151–171. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, B., & Jacobo-Suárez, M. (2019). Integrating American-Mexican students in Mexican classrooms. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 55(1), 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B., Mejía Arauz, R., & Aguilar Zepeda, R. (2017). La enseñanza equitativa para los niños retornados a México. Sinéctica, 48, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kasun, G. S. (2014). Hidden knowing of working-class transnational Mexican families in schools: Bridge-building, Nepantlera knowers. Ethnography and Education, 9(3), 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasun, G. S. (2015). The only Mexican in the room: Sobrevivencia as a way of knowing for Mexican transnational students and families. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 46(3), 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasun, G. S. (2016a). Interplay of a way of knowing among Mexican-origin transnationals: Chaining to the border and to transnational communities. Teachers College Record, 118(9), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasun, G. S. (2016b). Transnational Mexican-origin families’ ways of knowing: A framework toward bridging understandings in U.S. schools. Equity & Excellence in Education, 49(2), 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasun, G. S., Hernández, T., & Montiel, H. (2020). The engagement of transnationals in Mexican university classrooms: Points of entry towards recognition among future English teachers. Multicultural Perspectives, 22(1), 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasun, G. S., & Mora-Pablo, I. (2021). El anti-malinchismo contra el mexicano-transnacional: Cómo se puede transformar esa frontera limitante. Anales de Antropología, 55(1), 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M. (1991). Borders and boundaries of state and self at the end of empire. Journal of Historical Sociology, 4(1), 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, P. (2001). Transnational migration: Taking stock and future directions. Global Networks, 1(3), 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, P. (2003). Keeping feet in both worlds: Transnational practices and immigrant incorporation in the United States. In C. Joppke, & E. Morawska (Eds.), Toward assimilation and citizenship: Immigrants in liberal nation-states (pp. 177–194). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, P. (2009). Roots and routes: Understanding the lives of the second generation transnationally. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35(7), 1225–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, P., & Glick Schiller, N. (2004). Conceptualizing simultaneity: A transnational social field perspective on society. International Migration Review, 38(3), 1002–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, P., & Waters, M. C. (2002). Changing the face of home: The transnational lives of the second generation. Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Machado-Casas, M. (2006). Narrating education of new Indigenous/Latino transnational communities in the south [Unpublished dissertation]. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Machado-Casas, M. (2009). The politics of organic phylogeny: The art of parenting and surviving as transnational multilingual Latino indigenous immigrants in the U.S. The High School Journal, 92(4), 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, S. (1998). Theoretical and empirical contributions toward a research agenda for transnationalism. In M. P. Smith, & L. E. Guarnizo (Eds.), Transnationalism from below (pp. 64–100). Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mahler, S. (2001). Transnational relationships: The struggle to communicate across borders. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power, 7(4), 583–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masferrer, C., Hamilton, E. R., & Denier, N. (2019). Immigrants in their parental homeland: Half a million US-born minors settle throughout Mexico. Demography, 56(4), 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard-Warwick, J. (2008). The cultural and intercultural identities of transnational English teachers: Two case studies from the Americas. TESOL Quarterly, 42(4), 617–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menjívar, C. (2000). Fragmented ties: Salvadoran immigrant networks in America. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar, C. (2002). Living in two worlds? Guatemalan origin children in the United States and emerging transnationalism. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 28(3), 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexicanos Primero. (2015). Sorry: Learning English in Mexico. Mexicanos Primero. [Google Scholar]

- Mora Pablo, I., Lengeling, M. M., & Basurto Santos, N. M. (2015a). Crossing borders: Stories of transnationals becoming English language teachers in Mexico. Signum, 18(2), 326–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora Pablo, I., Lengeling, M. M., Rivas Rivas, L., Basurto Santos, N. M. B., & Villareal Ballesteros, A. C. (2015b). What does it mean to be transnational? Social construction of ethnic identity. In M. M. Lengeling, & I. Mora Pablo (Eds.), Perspectives on qualitative research (pp. 487–499). Universidad de Guanajuato. [Google Scholar]

- Mora Pablo, I., Rivas Rivas, L. A., Lengeling, M. M., & Crawford, T. (2015c). Transnationals becoming English teachers in Mexico: Effects of language brokering and identity formation. GIST Education and Learning Research Journal, 10, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora Vázquez, A., Trejo Guzmán, N. P., & Mora-Pablo, I. (2018). ‘I was lucky to be a bilingual kid, and that makes me who I am:’ The role of transnationalism in identity issues. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez Asomoza, A. (2019). Transnational youth and the role of social and sociocultural remittances in identity construction. Trabajos de Lingüística Aplicada; Campinas, 58(1), 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez Asomoza, A. (2022a). English has always been present: Transnational youths illustrating language dynamics in Zacatecas, Mexico. Migraciones Internacionales, 13(2), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez Asomoza, A. (2022b). Transnational English teachers negotiating translanguaging in and outside the classroom. MEXTESOL Journal, 46(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A. (1999). Flexible citizenship: The cultural logics of transnationality. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orellana, M. F., Thorne, B., Chee, A., & Lam, W. S. E. (2001). Transnational childhoods: The participation of children in processes of family migration. Social Problems, 48(4), 572–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panait, C., & Zúñiga, V. (2016). Children circulating between the U.S. and Mexico: Fractured schooling and linguistic ruptures. Mexican Studies, 32(2), 226–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja, A. D. (2005). Transnational ties and immigrant political incorporation: The case of Dominicans in Washington Heights, New York. International Migration, 43(4), 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrón, M. A. (2009). Transnational teachers of English in Mexico. The High School Journal, 92(4), 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrón, M. A., & Greybeck, B. (2014). Borderlands epistemologies and the transnational experience. GIST Education and Learning Research Journal, 8, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A. (1995). Segmented assimilation among new immigrant youth: A conceptual framework. In R. Rumbaut, & W. Cornelius (Eds.), California’s immigrant children: Theory, research, and implications (pp. 71–77). Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A. (1996). Introduction: Immigration and its aftermath. In A. Portes (Ed.), The new second generation (pp. 1–7). Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A., & Hao, L. (2004). The schooling of children of immigrants: Contextual effects on the educational attainment of the second generation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, 101(33), 11920–11927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 530(1), 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M. L. (1991). Arts of the contact zone. Profession, 91, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, F. (2000). Unequal schools, unequal chances. Harvard University, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Rendon, L. I., Nora, A., & Kanagala, V. (2014). Ventajas/assets y conocimiento/knowledge: Leveraging Latin@ strengths to foster student success. Center for Research and Policy Education. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas Rivas, L. (2013). Returnees’ identity construction at a BA TESOL program in Mexico. Profile, 15(2), 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Sánchez, L. (2013). Migración de retorno y experiencias de reinserción en la zona metropolitana de la Ciudad de México. Revista Interdisciplinar de Mobilidad Humana, 21(41), 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D. (2018). Racial and structural discrimination toward the children of indigenous Mexican immigrants. Race and Social Problems, 10(4), 306–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P. (2004). At home in two places: Second-generation Mexicanas and their lives as engaged tans-national [Ph.D. dissertation, University of California]. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, P. (2007a). Cultural authenticity and transnational Latina youth: Constructing a metanarrative across borders. Linguistics and Education, 18(3–4), 258–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P. (2007b). Urban immigrant students: How transnationalism shapes their world learning. The Urban Review, 39(5), 489–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P. (2008a). Coming of age across borders: Family, gender, and place in the lives of second-generation transnational mexicanas. In R. Márquez, & H. Romo (Eds.), Transformations of la familia on the U.S.-México border (pp. 185–208). Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, P. (2008b). Transnational students. In J. M. González (Ed.), Encyclopedia of bilingual education (pp. 857–860). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, P. (2009). Even beyond the local community: A close look at Latina youths return trips to Mexico. The High School Journal, 92(4), 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P., & Kasun, G. S. (2012). Connecting transnationalism to the classroom and to theories of immigrant student adaptation. Berkeley Review of Education, 3(1), 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, P., & Machado-Casas, M. (2009). At the intersection of transnationalism, Latina/o immigrants, and education. The High School Journal, 92, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez García, J., Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2010). Guía didáctica: Alumnos transnacionales. Las escuelas mexicanas frente a la globalización. Secretaria de Educación Pública. [Google Scholar]

- Serna-Gutiérrez, J. O. I., & Mora-Pablo, I. (2018). Critical incidents of transnational student-teachers in central Mexico. Profile, 20(1), 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, S. E., & López, Y. A. (2013). Infancia migrante y educación transnacional en la frontera México-Estados Unidos. Revista Sobre La Infancia y La Adolescencia, 4, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrbis, Z. (2008). Transnational families: Theorising migration, emotions and belonging. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 29(3), 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. C. (1998). Transnational localities: Community, technology and the politics of membership within the context of Mexico and U.S. Migration. In M. P. Smith, & L. E. Guarnizo (Eds.), Transnationalism from below (pp. 196–240). Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. C. (2006). Mexican New York: Transnational lives of new immigrants. UC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, L. (2018). Girlhood in the borderlands: Mexican teens caught in the crossroads of migration. New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco, C., & Suárez-Orozco, M. M. (1995). Transformations: Immigration, family life, and achievement motivation among Latino adolescents. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco, M. M., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2001). Children of immigration. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tacelosky, K. (2013). Community-based service-learning as a way to meet the linguistic needs of transnational students in Mexico. Hispania, 96(2), 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacelosky, K. (2018). Transnational education, language and identity: A case study from Mexico. Society Register, 2(2), 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, J. (1999). Globalization and culture. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trejo Guzmán, N. P., Mora Vázquez, A., Mora Pablo, I., Lengeling, M., & Crawford, T. (2016). Learning transitions of returnee English language teachers in Mexico. Lenguas en Contexto, 7, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. (2000). Mobile sociology. British Journal of Sociology, 51(1), 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling: US Mexican youth and the politics of caring. State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez-Ibáñez, C. (1996). Border visions: Mexican cultures of the Southwest United States. The University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas Torres, P., & Mora Pablo, I. (2015). El migrante de retorno y su profesionalización como maestro de inglés. Jóvenes en la Ciencia: Verano de Investigación Científica, 1(2), 1161–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, D. L. (2002). There’s no place like “home”: Emotional transnationalism and the struggles of second-generation Filipinos. In P. Levitt, & M. Waters (Eds.), The changing face of home: The transnational lives of the second generation (pp. 255–294). Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Wortham, S., Murillo, E., Jr., & Hamann, E. T. (Eds.). (2002). Education in the new Latino diaspora: Policy and the politics of identity. Ablex Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Zentella, A. C. (2002). Latin@ languages and identities. In M. Suárez Orozco, & M. Páez (Eds.), Latinos: Remaking America (pp. 321–338). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M. (1998). “Parachute kids” in southern California: The educational experience of Chinese children in transnational families. Educational Policy, 12(6), 682–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2006). Going home? Schooling in Mexico of transnational children. CONfines de Relaciones Internacionales y Ciencia Política, 2(4), 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2008). Escuelas nacionales, alumnos transnacionales: La migración México/Estados Unidos como fenómeno escolar. Estudios Sociológicos, 26(76), 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2009). Sojourners in Mexico with US school experience: A new taxonomy for transnational students. Comparative Education Review, 53(3), 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2013). Understanding American Mexican children. In B. Jensen, & A. Sawyer (Eds.), Regarding educación: Mexican American schooling, immigration, and binational improvement. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2015). Going to a home you have never been to: The return migration of Mexican and American-Mexican children. Children’s Geographies, 13(6), 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2020). Children’s voices about ‘return’ migration from the United States to Mexico: The 0.5 generation. Children’s Geographies, 19, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga, V., Hamann, E. T., & Sánchez García, J. (2008). Alumnos transfronterizos: Las escuelas mexicanas frente a la globalización. Secretaria de Educación Pública. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frausto-Hernandez, I. At the Intersection of Transnationalism, Identity, and Conocimiento: An Autoethnography. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111539

Frausto-Hernandez I. At the Intersection of Transnationalism, Identity, and Conocimiento: An Autoethnography. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111539

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrausto-Hernandez, Isaac. 2025. "At the Intersection of Transnationalism, Identity, and Conocimiento: An Autoethnography" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111539

APA StyleFrausto-Hernandez, I. (2025). At the Intersection of Transnationalism, Identity, and Conocimiento: An Autoethnography. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111539