Problematic Internet Use in Adolescents Is Driven by Internal Distress Rather Than Family or Socioeconomic Contexts: Evidence from South Tyrol, Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

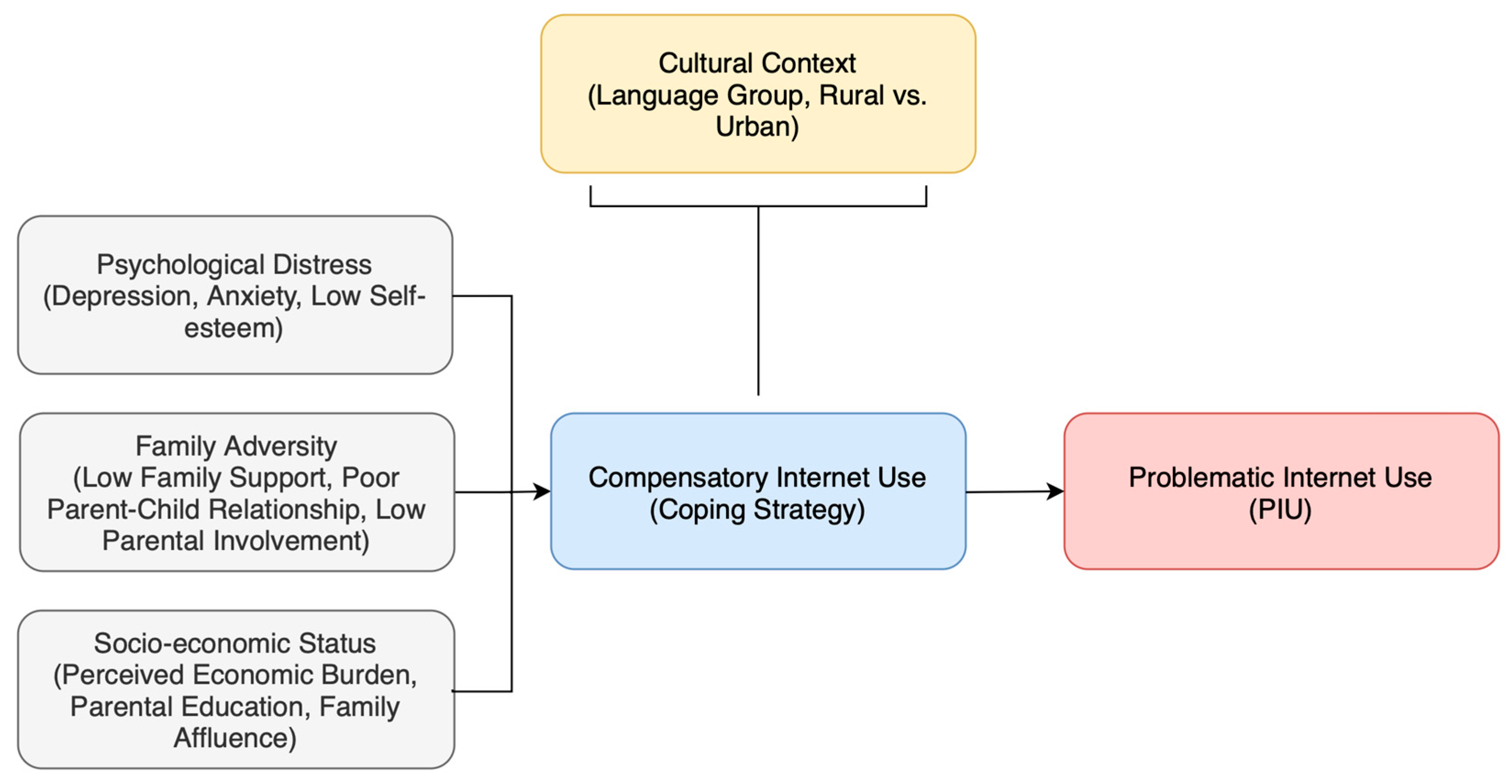

- PIU is closely linked to internalizing symptoms, such as depression and anxiety (Lam et al., 2009; Kaess et al., 2014; Günaydın et al., 2021). However, it remains unclear how these associations manifest in the specific psychosocial climate of post-pandemic South Tyrol.

- Poor parent-child relationships, low family support, and limited parental involvement have been repeatedly associated with an elevated PIU risk (X. Li et al., 2013; Saquib et al., 2023). The protective role of perceived family support has not yet been examined in this setting.

- While international studies have linked low SES and parental unemployment to problematic digital behavior (Durkee et al., 2012; Mei et al., 2016; Saquib et al., 2023), previous COP-S surveys in South Tyrol have not systematically assessed associations between socioeconomic status indicators and youth psychosocial outcomes. The 2025 wave of COP-S includes, for the first time, adolescent-reported subjective economic burden, allowing for a more nuanced analysis of perceived financial stress as a potential risk factor for depression.

- Higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms are positively associated with higher problematic Internet use (GPIUS-2 total score).

- Greater perceived family support is negatively associated with problematic Internet use.

- Subjective financial burden is positively associated with problematic Internet use, whereas structural sociodemographic factors (age, gender, parental education, family affluence, migration background, family language, and urbanity) show weak or no associations.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic and Cultural Variables

2.2.2. Psychological Distress

- Depressive symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), a 2-item screener validated in adolescent populations: “Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems: (1) little interest or pleasure in doing things, and (2) feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”); a total score of ≥3 indicates elevated depressive symptoms. Cronbach’s α is typically 0.79–0.83 in adolescent and adult samples (Kroenke et al., 2003; D’Argenio et al., 2013; Schuler et al., 2018).

- Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorders (GAD) subscale of the Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED), consisting of nine items rated on a 3-point scale from 0 (“not true”) to 2 (“very or often true”). A score of ≥9 indicates clinically relevant anxiety symptoms. Cronbach’s α is around 0.84–0.88; retest reliability r ≈ 0.70–0.80 (Birmaher et al., 1999; Crocetti et al., 2009; Weitkamp et al., 2010).

2.2.3. Family Dynamics

2.2.4. Problematic Internet Use (Primary Outcome)

- Preference for online social interaction (e.g., “I prefer online social interaction to face-to-face communication”).

- Mood regulation (e.g., “I use the Internet to feel better when I am down”).

- Cognitive preoccupation (e.g., “I think obsessively about going online when I am offline”).

- Compulsive Internet use (e.g., “I have difficulty controlling the amount of time I spend online”).

- Negative outcomes (e.g., “My Internet use has created problems for me in my life”).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- Depressive symptoms (PHQ-2 score)

- Anxiety symptoms (SCARED-GAD score)

- Perceived family support (MSPSS family subscale)

- Subjective economic burden

- Use of digital parental controls (Yes/No)

- Age group (11–14 vs. 15–19 years)

- Gender (male vs. female)

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

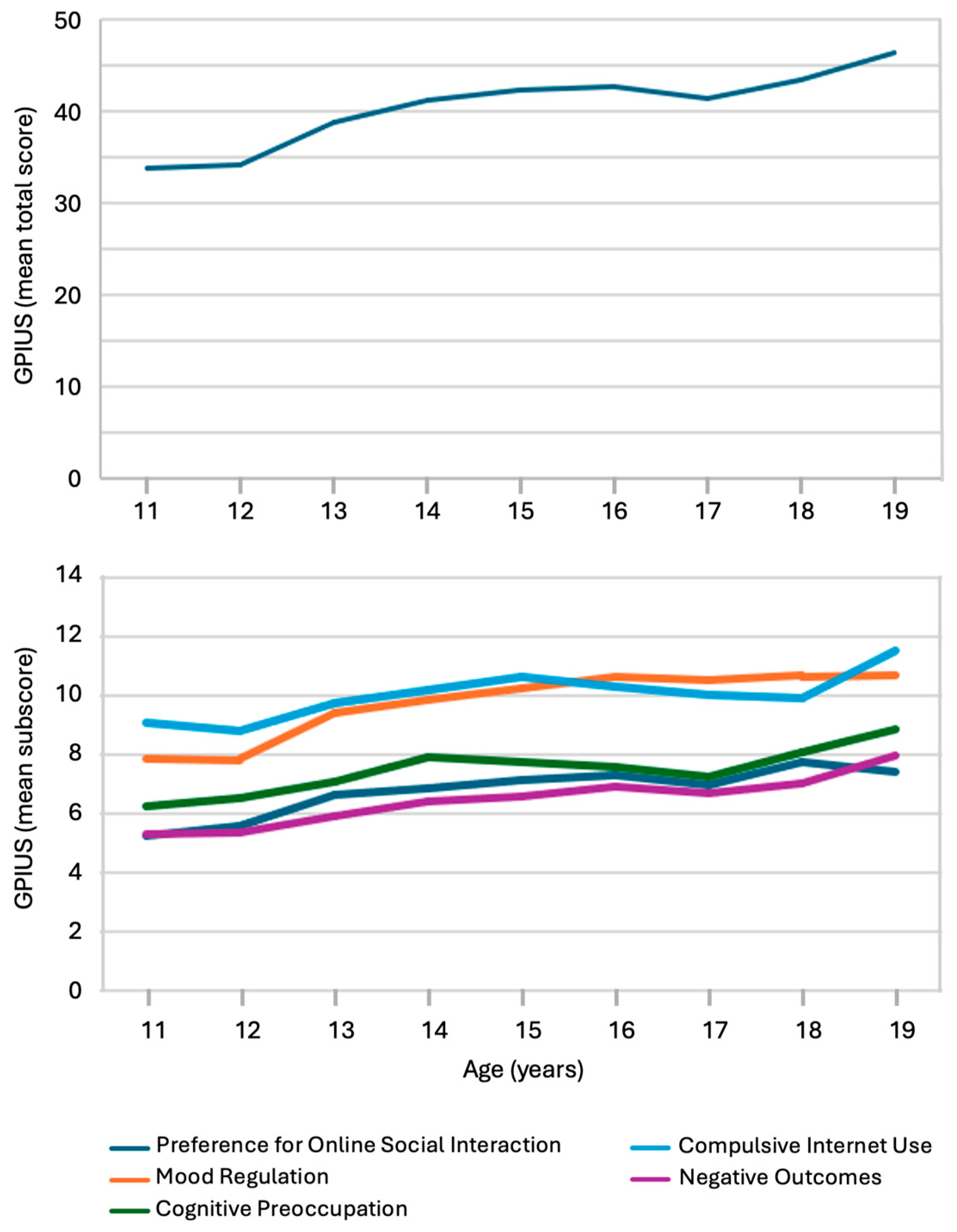

3.2. Age and Gender Differences in Problematic Internet Use

3.3. Problematic Internet Use by Language Group and Urbanity

3.4. Correlates of Problematic Internet Use

3.5. Problematic Internet Use and Demographic or Contextual Factors

3.6. Multivariable Predictors of Problematic Internet Use

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychological Distress as the Key Driver of Problematic Internet Use

4.2. Family Support and Digital Control Tools

4.3. Subjective Economic Burden and Structural Socioeconomic Status

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Implications and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CASMIN | Comparative Analysis of Social Mobility in Industrial Nations |

| CIUT | Compensatory Internet use theory |

| COP-S | Corona and Psyche South Tyrol |

| FAS | Family Affluence Scale |

| GAD | Generalized Anxiety Disorders |

| GPIUS | Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale |

| MSPSS | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support |

| PHQ | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| PIU | Problematic Internet use |

| SCARED | Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| VIF | Variance inflation factors |

References

- Amati, M., Tomasetti, M., Mariotti, L., Tarquini, L. M., Ciuccarelli, M., Poiani, M., Baldassari, M., Copertaro, A., & Santarelli, L. (2007). Study of a population exposed to occupational stress: Correlation among psychometrics tests and biochemical-immunological parameters. Giornale Italiano di Medicina del Lavoro ed Ergonomia, 29, 356–358. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, N., Sharma, M. K., & Marimuthu, P. (2021). Problematic Internet Use and its Association with Psychological Stress among Adolescents. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry, 37(3), 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. L., Steen, E., & Stavropoulos, V. (2017). Internet use and Problematic Internet Use: A systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(4), 430–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrivillaga, C., Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2020). Adolescents’ problematic internet and smartphone use is related to suicide ideation: Does emotional intelligence make a difference? Computers in Human Behavior, 110, 106375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrivillaga, C., Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2022). Psychological distress, rumination and problematic smartphone use among Spanish adolescents: An emotional intelligence-based conditional process analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 296, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baloğlu, M., Şahin, R., & Arpaci, I. (2020). A review of recent research in problematic internet use: Gender and cultural differences. Current Opinion in Psychology, 36, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, V., Piccoliori, G., Engl, A., & Wiedermann, C. J. (2024). Parental mental health, gender, and lifestyle effects on post-pandemic child and adolescent psychosocial problems: A cross-sectional survey in Northern Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(7), 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieri, V., Piccoliori, G., Mahlknecht, A., Plagg, B., Ausserhofer, D., Engl, A., & Wiedermann, C. J. (2023). Adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: The interplay of age, gender, and mental health outcomes in two consecutive cross-sectional surveys in Northern Italy. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barke, A., Nyenhuis, N., & Kröner-Herwig, B. (2014). The German version of the generalized pathological internet use scale 2: A validation study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(7), 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmaher, B., Brent, D. A., Chiappetta, L., Bridge, J., Monga, S., & Baugher, M. (1999). Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): A replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(10), 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggatz, T. (2023). Psychometric properties of the German version of the multidimensional perceived social support scale. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 18(4), e12540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniel-Nissim, M., & Sasson, H. (2018). Bullying victimization and poor relationships with parents as risk factors of problematic internet use in adolescence. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, W., Torsheim, T., Currie, C., & Zambon, A. (2006). The family affluence scale as a measure of national wealth: Validation of an adolescent self-report measure. Social Indicators Research, 78(3), 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauns, H., Scherer, S., & Steinmann, S. (2003). The CASMIN ducational classification in international comparative research. In J. H. P. Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, & C. Wolf (Eds.), Advances in cross-national comparison: A european working book for demographic and socio-economic variables (pp. 221–244). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, S. E. (2010). Theory and measurement of generalized problematic internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. A., & Fan, T. (2024). Adolescents’ mental health, problematic internet use, and their parents’ rules on internet use: A latent profile analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 156, 108232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X., Hong, X., & Chen, X. (2020). Profiles and sociodemographic correlates of Internet addiction in early adolescents in southern China. Addictive Behaviors, 106, 106385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocetti, E., Hale, W. W., Fermani, A., Raaijmakers, Q., & Meeus, W. (2009). Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED) in the general Italian adolescent population: A validation and a comparison between Italy and The Netherlands. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(6), 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Currie, C., Díaz, A. Y. A., Bosáková, L., & de Looze, M. (2024). The international family affluence scale (FAS): Charting 25 years of indicator development, evidence produced, and policy impact on adolescent health inequalities. SSM-Population Health, 25, 101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C., Molcho, M., Boyce, W., Holstein, B., Torsheim, T., & Richter, M. (2008). Researching health inequalities in adolescents: The development of the health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) family affluence scale. Social Science & Medicine, 66(6), 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Argenio, P., Minardi, V., Mirante, N., Mancini, C., Cofini, V., Carbonelli, A., Diodati, G., Granchelli, C., Trinito, M. O., & Tarolla, E. (2013). Confronto tra due test per la sorveglianza dei sintomi depressivi nella popolazione. Not Ist Super Sanità, 26(1), i–iii. [Google Scholar]

- Doğrusever, C., & Bilgin, M. (2025). From family social support to problematic internet use: A serial mediation model of hostility and depression. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkee, T., Kaess, M., Carli, V., Parzer, P., Wasserman, C., Floderus, B., Apter, A., Balazs, J., Barzilay, S., Bobes, J., Brunner, R., Corcoran, P., Cosman, D., Cotter, P., Despalins, R., Graber, N., Guillemin, F., Haring, C., Kahn, J., … Wasserman, D. (2012). Prevalence of pathological internet use among adolescents in Europe: Demographic and social factors. Addiction, 107(12), 2210–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B., Uzun, B., Aydin, C., Tan-Mansukhani, R., Vallejo, A., Saldaña-Gutierrez, A., Biswas, U. N., & Essau, C. A. (2021). Internet use during COVID-19 lockdown among young people in low- and middle-income countries: Role of psychological wellbeing. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 14, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fioravanti, G., Primi, C., & Casale, S. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the generalized problematic internet use scale 2 in an Italian sample. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(10), 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fumero, A., Marrero, R. J., Voltes, D., & Peñate, W. (2018). Personal and social factors involved in internet addiction among adolescents: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, F., Rega, V., & Boursier, V. (2021). Problematic internet use and emotional dysregulation among young people: A literature review. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 18(1), 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F., Gong, Z., Liu, H., Yi, P., Jia, Y., Zhuang, J., Shu, J., Huang, X., & Wu, Y. (2024). The impact of problematic internet use on adolescent loneliness-chain mediation effects of social support and family communication. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günaydın, N., Arıcı, Y. K., Kutlu, F. Y., & Demir, E. Y. (2021). The relationship between problematic Internet use in adolescents and emotion regulation difficulty and family internet attitude. Journal of Community Psychology, 50(2), 1135–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M., Durkee, T., Brunner, R., Carli, V., Parzer, P., Wasserman, C., Sarchiapone, M., Hoven, C., Apter, A., Balazs, J., Balint, M., Bobes, J., Cohen, R., Cosman, D., Cotter, P., Fischer, G., Floderus, B., Iosue, M., Haring, C., … Wasserman, D. (2014). Pathological Internet use among European adolescents: Psychopathology and self-destructive behaviours. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(11), 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormas, G., Critselis, E., Janikian, M., Kafetzis, D., & Tsitsika, A. (2011). Risk factors and psychosocial characteristics of potential problematic and problematic internet use among adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2003). The patient health questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F. T., & Kwan, J. L. (2017). Socioeconomic influence on adolescent problematic Internet use through school-related psychosocial factors and pattern of Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 68, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L. T., Peng, Z., Mai, J., & Jing, J. (2009). Factors associated with internet addiction among adolescents. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12(5), 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K., Chen, C., Chen, J., Liu, C., Chang, K., Fung, X. C., Chen, J., Kao, Y., Potenza, M. N., Pakpour, A. H., & Lin, C. (2023). Exploring mediational roles for self-stigma in associations between types of problematic use of internet and psychological distress in youth with ADHD. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 133, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G., Hou, G., Yang, D., Jian, H., & Wang, W. (2019). Relationship between anxiety, depression, sex, obesity, and internet addiction in Chinese adolescents: A short-term longitudinal study. Addictive Behaviors, 90, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X., Li, D., & Newman, J. (2013). Parental behavioral and psychological control and problematic internet use among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of self-control. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(6), 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y., Ren, Y., Barnhart, W. R., Cui, T., Zhang, J., & He, J. (2023). The connections among problematic usage of the internet, psychological distress, and eating disorder symptoms: A longitudinal network analysis in Chinese adolescents. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 23(3), 1991–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Xiao, J., E Kamper-DeMarco, K., & Fu, Z. (2023). Problematic internet use and suicidality and self-injurious behaviors in adolescents: Effects of negative affectivity and social support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 325, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukavská, K., Hrabec, O., Lukavský, J., Demetrovics, Z., & Király, O. (2022). The associations of adolescent problematic internet use with parenting: A meta-analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 135, 107423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., & Spada, M. M. (2018). The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 226, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S., Yau, Y. H., Chai, J., Guo, J., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Problematic internet use, well-being, self-esteem and self-control: Data from a high-school survey in China. Addictive Behaviors, 61, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, P., Favez, N., & Rigter, H. (2020). Parental and family factors associated with problematic gaming and problematic internet use in adolescents: A systematic literature review. Current Addiction Reports, 7(3), 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira-López, A., Rial-Boubeta, A., Guadix-García, I., Villanueva-Blasco, V. J., & Billieux, J. (2023). Prevalence of problematic Internet use and problematic gaming in Spanish adolescents. Psychiatry Research, 326, 115317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterlini, O. (2009). The South-Tyrol autonomy in Italy: Historical, political and legal aspects. In J. C. Oliveira, & P. Cardinal (Eds.), One country, two systems, three legal orders—Perspectives of evolution: Essays on Macau’s autonomy after the resumption of sovereignty by China. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Piqueras, J. A., Rico-Bordera, P., Galán, M., García-Oliva, C., Marzo, J. C., & Pineda, D. (2024). Problematic internet use profiles and their associated factors among adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 34(4), 1471–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphaely, S. G., Goldberg, S. B., Stowe, Z. N., & Moreno, M. A. (2024). Association between parental problematic internet use and adolescent depression. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saquib, N., Saquib, J., AlSalhi, A., Carras, M. C., Labrique, A. B., Al-Khani, A. M., Basha, A. C., & Almazrou, A. (2023). The associations between family characteristics and problematic Internet use among adolescents in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 28(1), 2256826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, M., Strohmayer, M., Mühlig, S., Schwaighofer, B., Wittmann, M., Faller, H., & Schultz, K. (2018). Assessment of depression before and after inpatient rehabilitation in COPD patients: Psychometric properties of the German version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9/PHQ-2). Journal of Affective Disorders, 232, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebre, S. B., Miltuze, A., & Limonovs, M. (2020). Integrating adolescent problematic internet use risk factors: Hyperactivity, inconsistent parenting, and maladaptive cognitions. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(7), 2000–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sela, Y., Zach, M., Amichay-Hamburger, Y., Mishali, M., & Omer, H. (2020). Family environment and problematic internet use among adolescents: The mediating roles of depression and fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsheim, T., Cavallo, F., Levin, K. A., Schnohr, C., Mazur, J., Niclasen, B., & Currie, C. (2016). Psychometric validation of the revised family affluence scale: A latent variable approach. Child Indicators Research, 9(3), 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth-Király, I., Morin, A. J., Hietajärvi, L., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2021). Longitudinal trajectories, social and individual antecedents, and outcomes of problematic internet use among late adolescents. Child Development, 92(4), E653–E673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitkamp, K., Romer, G., Rosenthal, S., Wiegand-Grefe, S., & Daniels, J. (2010). German screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): Reliability, validity, and cross-informant agreement in a clinical sample. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 4(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W., Pu, J., He, R., Yu, M., Xu, L., He, X., Chen, Z., Gan, Z., Liu, K., Tan, Y., & Xiang, B. (2022). Demographic characteristics, family environment and psychosocial factors affecting internet addiction in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 315, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 11–14 years | 809 | 52.2% |

| 15–19 years | 740 | 47.8% | |

| Gender 1 | Female | 772 | 49.8% |

| Male | 777 | 50.1% | |

| Family language | German | 1264 | 81.8% |

| Italian | 222 | 14.4% | |

| Ladin | 41 | 2.7% | |

| Other | 18 | 1.2% | |

| Migration background | Yes | 129 | 8.5% |

| No | 1392 | 91.5% | |

| Parental education (CASMIN) | Low (primary/lower secondary) | 284 | 18.4% |

| Medium (upper secondary) | 646 | 41.7% | |

| High (tertiary) | 610 | 39.6% | |

| Family structure | Two-parent household | 1359 | 88.1% |

| Single-parent household | 183 | 11.9% | |

| Urbanity | Urban | 447 | 28.8% |

| Rural | 1103 | 71.2% | |

| Subjective economic burden | Not at all burdened (1) 2 | 25 | 1.6% |

| Slightly to moderately burdened (2–3) | 602 | 38.9% | |

| Strongly to extremely burdened (4–5) | 919 | 59.5% | |

| Family Affluence Scale (FAS III) | Low | 268 | 17.5% |

| Medium | 870 | 56.8% | |

| High | 395 | 25.8% | |

| Use of digital parental controls 3 | Yes | 734 | 53.1% |

| No | 628 | 45.4% | |

| Use of parental help with school | Never/rarely | 263 | 17.0% |

| Sometimes/often/always | 1155 | 74.5% | |

| Never asked for help | 130 | 8.4% |

| GPIUS-2 Score | Score, Mean (SD) | Gender | Age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (Mean) | Males (Mean) | p-Value | 11–14 Years | 15–19 Years | p-Value | ||

| Total score | 39.61 (19.49) | 39.91 | 39.30 | n.s. | 36.89 | 42.59 | <0.001 |

| Preference for Online Social Interaction | 6.61 (4.50) | 6.67 | 6.55 | n.s. | 6.03 | 7.24 | <0.001 |

| Mood Regulation | 9.58 (5.60) | 10.18 | 8.97 | <0.001 | 8.73 | 10.51 | <0.001 |

| Cognitive Preoccupation | 7.31 (4.60) | 7.24 | 7.37 | n.s. | 6.94 | 7.70 | <0.001 |

| Compulsive Internet Use | 9.86 (5.20) | 9.76 | 9.97 | n.s. | 9.46 | 10.31 | 0.001 |

| Negative Outcomes | 6.29 (3.90) | 6.19 | 6.39 | n.s. | 5.78 | 6.85 | <0.001 |

| GPIUS-2 Score, Mean (SD) | German (n = 1264) | Italian (n = 222) | Ladin (n = 41) | p-Value | Urban (n = 447) | Rural (n = 1103) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | 39.49 (19.55) | 40.50 (19.76) | 40.02 (17.84) | n.s. | 39.56 (20.39) | 39.63 (19.12) | n.s. |

| Preference for Online Social Interaction | 6.49 (4.44) | 7.30 (4.87) | 7.05 (4.26) | 0.028 | 6.76 (4.71) | 6.56 (4.43) | n.s. |

| Mood Regulation | 9.50 (5.67) | 10.03 (5.39) | 9.88 (5.50) | n.s. | 9.62 (5.75) | 9.55 (5.55) | n.s. |

| Cognitive Preoccupation | 7.33 (4.64) | 7.19 (4.60) | 7.34 (4.09) | n.s. | 7.25 (4.60) | 7.31 (4.61) | n.s. |

| Compulsive Internet Use | 9.91 (5.24) | 9.70 (5.10) | 9.80 (5.08) | n.s. | 9.68 (5.18) | 9.93 (5.20) | n.s. |

| Negative Outcomes | 6.27 (3.91) | 6.27 (3.81) | 5.95 (3.35) | n.s. | 6.25 (3.93) | 6.27 (3.87) | n.s. |

| GPIUS-2 Score | SCARED | PHQ-2 | MSPSS | FAS III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Family | Friends | Other | ||||

| Total score | 0.405 *** | 0.419 *** | −0.097 *** | −0.112 *** | −0.112 *** | −0.096 *** | n.s. |

| Preference for Online Social Interaction | 0.291 *** | 0.356 *** | −0.151 *** | −0.128 *** | −0.164 *** | −0.151 *** | n.s. |

| Mood Regulation | 0.420 *** | 0.431 *** | −0.081 *** | −0.096 *** | −0.074 ** | −0.055 * | n.s. |

| Cognitive Preoccupation | 0.279 *** | 0.281 *** | −0.084 *** | −0.086 ** | −0.084 ** | −0.092 *** | n.s. |

| Compulsive Internet Use | 0.316 *** | 0.316 *** | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Negative Outcomes | 0.354 *** | 0.356 *** | −0.101 *** | −0.125 *** | −0.129 *** | −0.105 *** | n.s. |

| GPIUS-2 Score | Migration Background (Yes vs. No) | Single Parenthood (Yes vs. No) | Parental Education (Low/Med/High) | Worry About Higher Prices (Spearman’s ρ) | Parental Control Tool (Yes vs. No) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Score | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.148 *** | n.s. |

| Preference for Online Social Interaction | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.149 *** | 0.003 ** |

| Mood Regulation | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.169 *** | 0.004 ** |

| Cognitive Preoccupation | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.122 *** | <0.001 *** |

| Compulsive Internet Use | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.117 *** | 0.010 * |

| Negative Outcomes | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | 0.139 *** | n.s. |

| Predictor Variable | B (Unstandardized Coefficient) | Standard Error | Β (Standardized Coefficient) | t | p-Value | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 20.446 | 3.660 | — | 5.587 | <0.001 | [13.267, 27.625] |

| Age (in years) | 0.790 | 0.205 | 0.095 | 3.859 | <0.001 | [0.388, 1.191] |

| Perceived Family Support (MSPSS total score) | −0.715 | 0.333 | −0.052 | −2.147 | 0.032 | [−1.368, −0.062] |

| Anxiety Symptoms (SCARED score) | 1.432 | 0.104 | 0.349 | 13.827 | <0.001 | [1.229, 1.635] |

| Subjective Financial Burden (Price Increase Concern) | 1.307 | 0.394 | 0.083 | 3.316 | 0.001 | [0.534, 2.081] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Piccoliori, G.; Engl, A. Problematic Internet Use in Adolescents Is Driven by Internal Distress Rather Than Family or Socioeconomic Contexts: Evidence from South Tyrol, Italy. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111534

Wiedermann CJ, Barbieri V, Piccoliori G, Engl A. Problematic Internet Use in Adolescents Is Driven by Internal Distress Rather Than Family or Socioeconomic Contexts: Evidence from South Tyrol, Italy. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111534

Chicago/Turabian StyleWiedermann, Christian J., Verena Barbieri, Giuliano Piccoliori, and Adolf Engl. 2025. "Problematic Internet Use in Adolescents Is Driven by Internal Distress Rather Than Family or Socioeconomic Contexts: Evidence from South Tyrol, Italy" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111534

APA StyleWiedermann, C. J., Barbieri, V., Piccoliori, G., & Engl, A. (2025). Problematic Internet Use in Adolescents Is Driven by Internal Distress Rather Than Family or Socioeconomic Contexts: Evidence from South Tyrol, Italy. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111534