Performance Anxiety and Academic Performance: Academic, Physical, and Psychological Effects in Students of Higher Studies in Music

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Psychological Determinants of Artistic Interpretation

1.2. Physical Activity and Its Impact on the MPA

2. Objectives

3. Methodology

3.1. Population and Sample

3.2. Procedure

3.3. Instruments

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of MPA, Psychological Determinants, and Physical Activity

4.2. Comparison by Gender, Course, and Musical Specialty

4.3. Correlations Among Psychological and Behavioral Variables

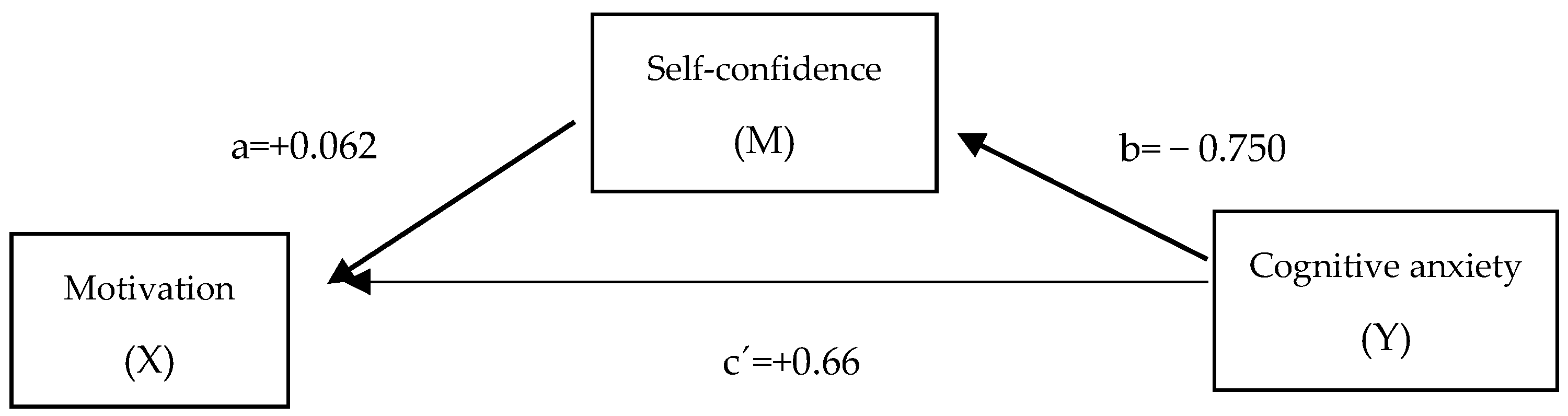

4.4. Mediation Analysis: Role of Self-Confidence

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Study Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MPA | Musical stage anxiety |

| PA | Physical activity |

References

- Anderson, E., & Shivakumar, G. (2013). Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 4(27), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L. S., Wasley, D., Perkins, R., Redding, E., Ginsborg, J., & Williamon, A. (2017). Fit to perform: An investigation of higher education music students’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward health. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, L. S., Wasley, D., Redding, E., Atkins, L., Perkins, R., Ginsborg, J., & Williamon, A. (2020). Fit to perform: A profile of higher education music students’ physical fitness. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Bueno, C., Pesce, C., Cavero-Redondo, I., Sánchez-López, M., Garrido-Miguel, M., & Martínez-Vizcaíno, V. (2017). Academic achievement and physical activity: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 140(6), e20171498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Benedek, M., Jauk, E., Sommer, M., Arendasy, M., & Neubauer, A. C. (2014). Intelligence, creativity, and cognitive control: The common and differential involvement of executive functions in intelligence and creativity. Intelligence, 46, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M., & Concina, E. (2014). The role of coping strategy and experience in predicting music performance anxiety. Musicae Scientiae, 18(2), 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S. J., & Asare, M. (2011). Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(11), 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braden, A. M., Osborne, M. S., & Wilson, S. J. (2015). Psychological intervention reduces self-reported performance anxiety in high school music students. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. M., & Palmer, C. (2013). Auditory and motor imagery modulate learning in music performance. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burin, A. B., & Osório, F. D. L. (2016). Interventions for music performance anxiety: Results from a systematic literature review. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo), 43(5), 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butković, A., Vukojević, N., & Carević, S. (2021). Music performance anxiety and perfectionism in Croatian musicians. Psychology of Music, 50(1), 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, O., Zarza-Alzugaray, F., Cuartero, L. M., & Orejudo, S. (2023). General musical self-efficacy scale: Adaptation and validation of a version in Spanish. Psychology of Music, 51(3), 838–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C., Driscoll, T., & Ackermann, B. (2013). Effect of a musicians’ exercise intervention on performance-related musculoskeletal disorders. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 29(4), 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conger, R. D., Ge, X., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., & Simons, R. L. (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65(2), 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, L. L., & Perna, F. M. (2004). The benefits of exercise for the clinically depressed. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 6(3), 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H., Lauche, R., Anheyer, D., Pilkington, K., de Manincor, M., Dobos, G., & Ward, L. (2018). Yoga for anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depression and Anxiety, 35(9), 830–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creech, A., & Hallam, S. (2011). Learning a musical instrument: The influence of interpersonal interaction on outcomes for school-aged pupils. Psychology of Music, 39(1), 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalia, G. (2004). Cómo superar la ansiedad escénica en músicos: Un método eficaz para dominar los nervios ante las actuaciones musicales. Mundimúsica ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- De Filippis, R., & Al Foysal, A. (2025). Associations between music listening habits and mental health: A cross-sectional analysis. Open Access Library Journal, 12, e13196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J. E., Hillman, C. H., Castelli, D., Etnier, J. L., Lee, S., Tomporowski, P., Lambourne, K., & Szabo-Reed, A. N. (2016). Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: A systematic review. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 48(6), 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, S., Penny, K., & Kynn, M. (2024). The effectiveness of physical activity interventions in improving higher education students’ mental health: A systematic review. Health Promotion International, 39(2), daae027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elosua, R., Marrugat, J., Molina, L., Pons, S., & Pujol, E. (1994). Validation of the minnesota leisure time physical activity questionnaire in Spanish men. American Journal of Epidemiology, 139(12), 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esplen, M. J., & Hodnett, E. (1999). A pilot study investigating student musicians’ experiences of guided imagery as a technique to manage performance anxiety. Journal of Music Therapy, 36(1), 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, P., & Bonneville-Roussy, A. (2015). Self-determined motivation for practice in university music students. Psychology of Music, 46(4), 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernholz, I., Mumm, J. L. M., Plag, J., Noeres, K., Rotter, G., Willich, S. N., Ströhle, A., Berghöfer, A., & Schmidt, A. (2019). Performance anxiety in professional musicians: A systematic review on prevalence, risk factors and clinical treatment effects. Psychological Medicine, 49(14), 2287–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, K., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2016). Imagery-based interventions for music performance anxiety: An integrative review. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 31(4), 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granic, I., Lobel, A., & Engels, R. C. (2014). The benefits of playing video games. American Psychologist, 69(1), 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, L., & Guan, S. (2015). Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 21, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, C., Meixner, F., Wiebking, C., & Gilg, V. (2020). Regular physical activity, short-term exercise, mental health, and well-being among university students: The results of an online and a laboratory study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K., Beckman, E. M., Ng, N., Dingle, G. A., Han, R., James, K., Winkler, E., Stylianou, M., & Gomersall, S. R. (2024). Effectiveness of physical activity interventions on undergraduate students’ mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Promotion International, 39(3), daae054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huawei, Z., & Salarzadeh, H. (2024). Effects of social support on music performance anxiety among university music students: Chain mediation of emotional intelligence and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1389681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. Released. (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 25.0). IBM Corp.

- Jadue, G. (2001). Algunos efectos de la ansiedad en el rendimiento escolar. Estudios Pedagógicos, 27, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. (2024). Impact of music learning on students’ psychological development with mediating role of self-efficacy and self-esteem. PLoS ONE, 19(9), e0309601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T. (2009). The factor structure of the revised Kenny Music Performance Anxiety Inventory. In International symposium on performance science (pp. 37–41). Association Européenne des Conservatoires. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D. T. (2011). The psychology of music performance anxiety. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T. (2023). The Kenny music performance anxiety inventory (K-MPAI): Scale construction, cross-cultural validation, theoretical underpinnings, and diagnostic and therapeutic utility. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1143359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalsa, S. B. S., Butzer, B., Shorter, S. M., Reinhardt, K. M., & Cope, S. (2009). Yoga reduces performance anxiety in adolescent musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 24(4), 162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsner, J., Wilson, S. J., & Osborne, M. S. (2023). Music performance anxiety: The role of early parenting experiences and cognitive schemas. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1185296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. A., Ju, Y. J., Lee, J. E., Hyun, I. S., Nam, J. Y., Han, K.-T., & Park, E.-C. (2016). The relationship between sports facility accessibility and physical activity among Korean adults. BMC Public Health, 16, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefcourt, H. (2014). Locus of control: Current trends in theory and research. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lemola, S., Perkinson-Gloor, N., Brand, S., Dewald-Kaufmann, J. F., & Grob, A. (2015). Adolescents’ electronic media use at night, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms in the smartphone age. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(2), 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupiáñez, M., Ortiz, F. de P., Vila, J., & Muñoz, M. A. (2021). Predictors of music performance anxiety in conservatory students. Psychology of Music, 50(4), 1005–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Antón, M., Vázquez, S. B., & Cava, M. J. (2007). La satisfacción con la vida en la adolescencia y su relación con la autoestima y el ajuste escolar. Anuario de Psicología, 38(2), 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Matei, R., & Ginsborg, J. (2020). Physical activity, sedentary behavior, anxiety, and pain among musicians in the United Kingdom. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 560026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarolo, I., Burwell, K., & Schubert, E. (2023). Teachers’ approaches to music performance anxiety management: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1205150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, G. E., & McCormick, J. (2006). Self-efficacy and music performance. Psychology of Music, 34(3), 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, K., Stojanovska, L., Polenakovic, M., Bosevski, M., & Apostolopoulos, V. (2017). Exercise and mental health. Maturitas, 106, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miksza, P., & Tan, L. (2015). Predicting collegiate wind players’ practice efficiency, flow, and self-efficacy for self-regulation: An exploratory study of relationships between teachers’ instruction and students’ practicing. Journal of Research in Music Education, 63(2), 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, E., & Clares-Clares, E. (2023). Scenic anxiety in professional music education studies learners. LEEME, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M. M. D., Loots, J. M., & Van Niekerk, R. L. (2014). The effect of various physical exercise modes on perceived psychological stress. South African Journal of Sports Medicine, 26, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nogaj, A. A. (2017). Locus of control and styles of coping with stress in students educated at polish music and visual art schools–a cross-sectional study. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 48(2), 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokenna, E. N., Sewagegn, A. A., & Falade, T. A. (2022). Effects of educational music training on music performance anxiety and stress response among first-year undergraduate music education students. Medicine, 101(48). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okan, H., & Usta, B. (2021). Conservatory students’ music performance anxiety and educational expectations: A qualitative study. Asian Journal of Education and Training, 7(4), 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabe, M. N. (2020). Los Beneficios del Yoga y la Meditación para el Aprendizaje de un Instrumento Musical [tesis de maestría, Instituto Politécnico de Castelo Branco]. Repositórios Científicos de Acesso Aberto de Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Orejudo, S., Zarza-Alzugaray, F. J., Casanova, O., & McPherson, G. E. (2021). Social support as a facilitator of musical self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 722082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, M. S., & Franklin, J. (2002). Cognitive processes in music performance anxiety. Australian Journal of Psychology, 54(2), 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, M. S., & Kenny, D. T. (2005). Development and validation of a music performance anxiety inventory for gifted adolescent musicians. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19(7), 725–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, M. S., & Kenny, D. T. (2008). The role of sensitizing experiences in music performance anxiety in adolescent musicians. Psychology of Music, 36(4), 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J., & Qin, X. (2025). Exploring musical self-efficacy and performance anxiety in undergraduate music students in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1575591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özen Kutanis, R., Mesci, M., & Övdür, Z. (2011). The effects of locus of control on learning performance: A case of an academic organization. Journal of Economic and Social Studies, 1(2), 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, F. (1996). Self-Efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research, 66(4), 543–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-León, P., Velasco, R., & Calvo, Á. (2022). Progresión metodológica con soporte musical para un nuevo sistema de actividad física en tapiz rodante en adultos: Cinta dance. Estudio de caso. Retos: Nuevas Perspectivas de Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 45, 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgi, I., Creech, A., & Welch, G. (2011). Perceived performance anxiety in advanced musicians specializing in different musical genres. Psychology of Music, 41(1), 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgi, I., Hallam, S., & Welch, G. F. (2007). A conceptual framework for understanding musical performance anxiety. Research Studies in Music Education, 28(1), 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patston, T., & Osborne, M. (2016). The developmental features of music performance anxiety and perfectionism in school age music students. Performance Enhancement & Health, 4(1–2), 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzello, S. J., Landers, D. M., Hatfield, B. D., Kubitz, K. A., & Salazar, W. (1991). A meta-analysis on the anxiety-reducing effects of acute and chronic exercise. Outcomes and mechanisms. Sports Medicine, 11(3), 143–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, D. (2001). Helping children to build self-esteem. Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, P. (2013). La validez y la eficacia de los ejercicios respiratorios para reducir la ansiedad escénica en el aula de música. Revista Internacional de Educación Musical, 1(1), 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J. (2007). Perceptions of the availability of recreational physical activity facilities on a university campus. Journal of American College Health, 55(4), 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, L., & Williamon, A. (2011). Measuring distinct types of musical self-efficacy. Psychology of Music, 39(3), 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A., Gracia, L., Llorente, F. J., Cadenas, C., Marmol, A., Gil, J. J., Moliner, D., & Ubago, E. (2023). Is higher physical fitness associated with better psychological health in young pediatric cancer survivors? A cross-sectional study from the iBoneFIT project. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 33(7), 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Comellas, A., Pera, G., Baena-Díez, J. M., Mundet, X., Alzamora, M., Elosua, R., & Toran, P. (2012). Validación de una versión reducida en español del cuestionario de actividad física en el tiempo libre de Minnesota (VREM). Revista Española de Salud Pública, 86(5), 495–508. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R., & Deci, E. L. (2000). La Teoría de la Autodeterminación y la Facilitación de la Motivación Intrínseca, el Desarrollo Social, y el Bienestar. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J. F., Cerin, E., Conway, T. L., Adams, M. A., Frank, L. D., Pratt, M., Salvo, D., Schipperijn, J., Smith, G., Cain, K. L., Davey, R., Kerr, J., Lai, P. C., Mitáš, J., Reis, R., Sarmiento, O. L., Schofield, G., Troelsen, J., Van Dyck, D., … Owen, N. (2016). Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: A cross-sectional study. Lancet (London, England), 387(10034), 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P. (2001). Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 21(1), 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, E., & Chesky, K. (2011). Social support and performance anxiety of college music students. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 26(3), 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, T. A., Juncos, D. G., & Winter, D. (2020). Piloting a new model for treating music performance anxiety: Training a singing teacher to use acceptance and commitment coaching with a student. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoebridge, A., & Osborne, M. (2025). Well-being for young elite musicians: Development of a well-being protocol. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1401511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B., Olds, T., Curtis, R., Dumuid, D., Virgara, R., Watson, A., Szeto, K., O’Connor, E., Ferguson, T., Eglitis, E., Miatke, A., Simpson, C. E. M., & Maher, C. (2023). Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(18), 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, S. H., & Rapee, R. M. (2016). The etiology of social anxiety disorder: An evidence-based model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 86, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stults-Kolehmainen, M. A., & Sinha, R. (2014). The effects of stress on physical activity and exercise. Sports Medicine, 44(1), 81–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H. L., Jacobs, D. R., Schucker, B., Knudsen, J., Leon, A. S., & Debacker, G. (1978). A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 31(12), 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, P. C., Karageorghis, C. I., Curran, M. L., Martin, O. V., & Parsons-Smith, R. L. (2020). Effects of music in exercise and sport: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 146(2), 91–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuber, M., Leyhr, D., & Sudeck, G. (2024). Physical activity improves stress load, recovery, and academic performance-related parameters among university students: A longitudinal study on daily level. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovar, H. G. (2018). Relación entre condición física y lesiones músculo-esqueléticas en estudiantes de música. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte, 7(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulloa, H., Gutiérrez, M. A., Nares, M. L., & Gutiérrez, S. L. (2020). Importancia de la Investigación Cualitativa y Cuantitativa para la Educación. Educateconciencia, 16(17), 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urruzola, M. V., & Bernaras, E. (2019). Aprendizaje musical y ansiedad escénica en edades tempranas: 8-12 años. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 24(2), 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., & Yang, R. (2024). The influence of music performance anxiety on career expectations and self-efficacy among music students. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1411944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G. D., & Roland, D. (2002). Performance anxiety. In R. Parncutt, & G. E. McPherson (Eds.), The science and psychology of music performance (pp. 47–61). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wipfli, B. M., Rethorst, C. D., & Landers, D. M. (2008). The anxiolytic effects of exercise: A meta-analysis of randomized trials and dose–response analysis. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 30(4), 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolk, S., & Bloom, D. (1978). The interactive effects of locus of control and situational stress upon performance accuracy and time. Journal of Personality, 46(2), 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y., Lei, P., Huang, Z., Yu, H., & Zhang, H. (2025). The impact of professional music performance competence on performance anxiety: The mediating role of psychological risk and moderating role of psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1565215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youngstedt, S. D., O’Connor, P. J., Crabbe, J. B., & Dishman, R. K. (1998). Acute exercise reduces caffeine-induced anxiogenesis. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 30, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarza-Alzugaray, F. J., Casanova, O., McPherson, G. E., & Orejudo, S. (2020). Music self-efficacy for performance: An explanatory model based on social support. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Specialty | Gender | n = Students | n = Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Cruz de Tenerife | Interpretation | Men | n = 12 | n = 19 |

| Women | n = 7 | |||

| Gran Canaria | Interpreting | Men | n = 11 | n = 37 |

| Women | n = 9 | |||

| I prefer not to say | n = 1 | |||

| Pedagogy | Men | n = 9 | ||

| Women | n = 7 | |||

| Total | n = 56 |

| Dimension | Subdimension | Objectives | Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSA | Cognitive anxiety | SO1, SO2, SO3 | K-MPAI |

| Somatic anxiety | SO1, SO2, SO3 | K-MPAI | |

| Psychological resources | Self-confidence | SO1, SO2, SO3, SO5 | K-MPAI & DPAA |

| Motivation | SO1, SO2, SO3, SO5 | DPAA | |

| Coping | SO1, SO3, SO5 | DPAA | |

| Attentional control | SO1, SO3, SO5 | K-MPAI & DPAA | |

| Visualization | SO1, SO3, SO5 | DPAA | |

| Physical activity | Moderate activity | SO4 | MLTPAQ |

| Vigorous activity | SO4 | MLTPAQ | |

| Total energy expenditure | SO4 | MLTPAQ |

| Dimension | p Gender | p Course | p Specialty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive anxiety (K-MPAI) | 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.14 |

| Somatic anxiety (K-MPAI) | 0.94 | 0.61 | 0.23 |

| Self-confidence (K-MPAI) | 0.45 | 0.60 | 0.02 * |

| Attentional control (K-MPAI) | 0.32 | 0.84 | 0.19 |

| Self-confidence (DPAA) | 0.59 | 0.99 | 0.04 * |

| Motivation (DPAA) | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.21 |

| Coping (DPAA) | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.14 |

| Visualization (DPAA) | 0.26 | 0.86 | 0.01 * |

| Attentional control (DPAA) | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.12 |

| Moderate PA (MLTPAQ) | 0.22 | 0.50 | 0.47 |

| Vigorous PA (MLTPAQ) | 0.19 | 0.69 | 0.37 |

| MET total (MLTPAQ) | 0.36 | 0.78 | 0.39 |

| Dimension | Test | Statistician H | Specialty | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-confidence (K-MPAI) | Kruskal–Wallis | 10.13 | 1 | 3.47 | 0.018 |

| 2 | 3.19 | ||||

| Visualization (DPAA) | Kruskal–Wallis | 11.47 | 0.012 | ||

| Relation | Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Motivation—Self-confidence (a) | +0.062 |

| Self-confidence—Anxiety (b) | −0.750 |

| Motivation—Direct anxiety (c′) | +0.660 |

| Indirect effect (a × b) | −0.046 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernández-Dionis, P.; Pérez-Jorge, D.; Borges-Hernández, P.J.; Santos-Álvarez, A.G. Performance Anxiety and Academic Performance: Academic, Physical, and Psychological Effects in Students of Higher Studies in Music. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111532

Hernández-Dionis P, Pérez-Jorge D, Borges-Hernández PJ, Santos-Álvarez AG. Performance Anxiety and Academic Performance: Academic, Physical, and Psychological Effects in Students of Higher Studies in Music. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111532

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-Dionis, Paula, David Pérez-Jorge, Pablo J. Borges-Hernández, and Anthea Gara Santos-Álvarez. 2025. "Performance Anxiety and Academic Performance: Academic, Physical, and Psychological Effects in Students of Higher Studies in Music" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111532

APA StyleHernández-Dionis, P., Pérez-Jorge, D., Borges-Hernández, P. J., & Santos-Álvarez, A. G. (2025). Performance Anxiety and Academic Performance: Academic, Physical, and Psychological Effects in Students of Higher Studies in Music. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111532