How Body Esteem Influences Virtual Model Selection and Intention to Use Virtual Fitting Rooms

Abstract

1. Introduction

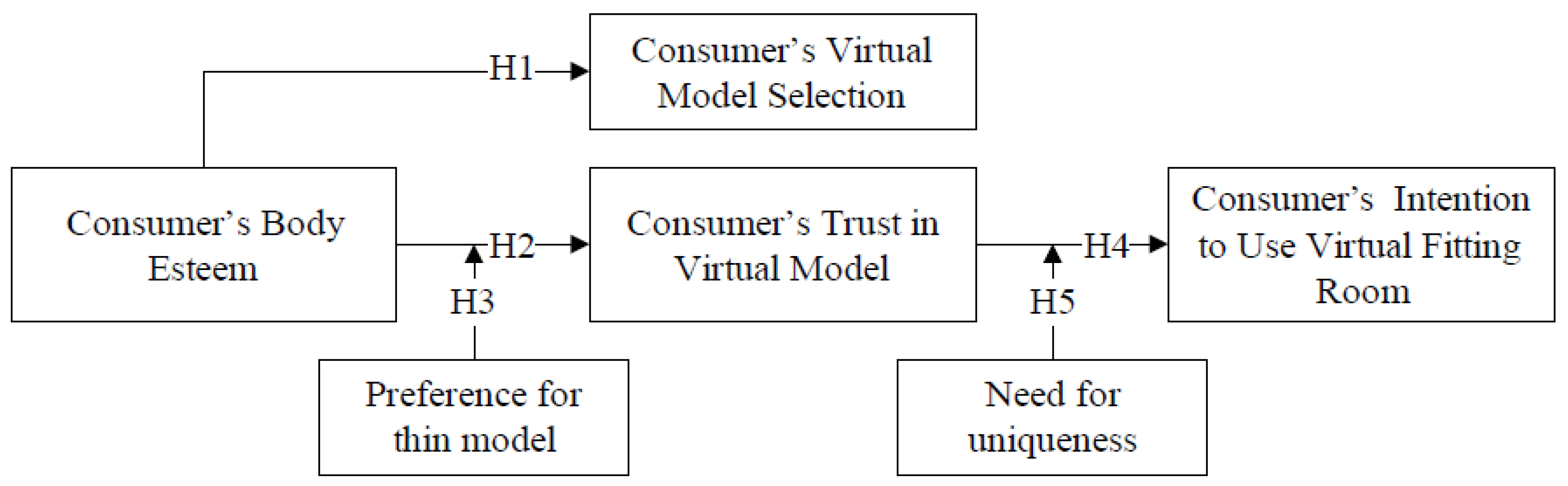

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

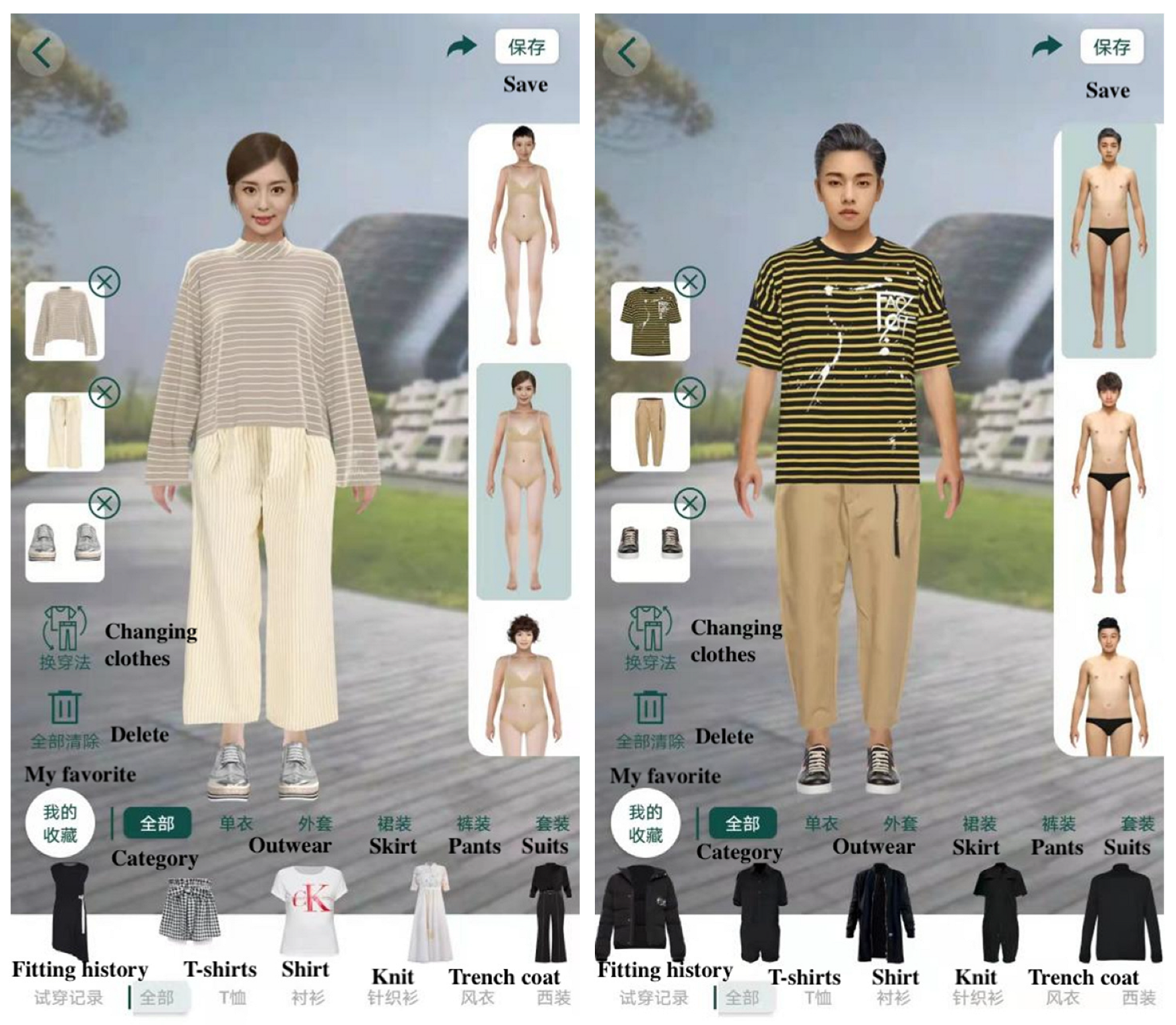

2.1. Virtual Fitting Rooms and Virtual Models

2.2. Consumer’s Body Esteem and Virtual Model Selection

2.3. Consumer’s Body Esteem and Trust in Virtual Models

2.4. Consumer’s Body Esteem, Preference for Thin Models, and Trust in Virtual Models

2.5. Consumer’s Body Esteem, Trust in Virtual Models, and Consumer’s Intention to Use Virtual Fitting Rooms

2.6. Trust in Virtual Models, Need for Uniqueness, and Consumer’s Intention to Use Virtual Fitting Room

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Procedures

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Property Assessment and Common Method Variance

4.2. Consumer’s Body Esteem and Virtual Model Selection

4.3. Consumer’s Body Esteem, Preference for Thin Models, and Trust in Virtual Models

4.4. The Mediating Role of Trust in Virtual Models

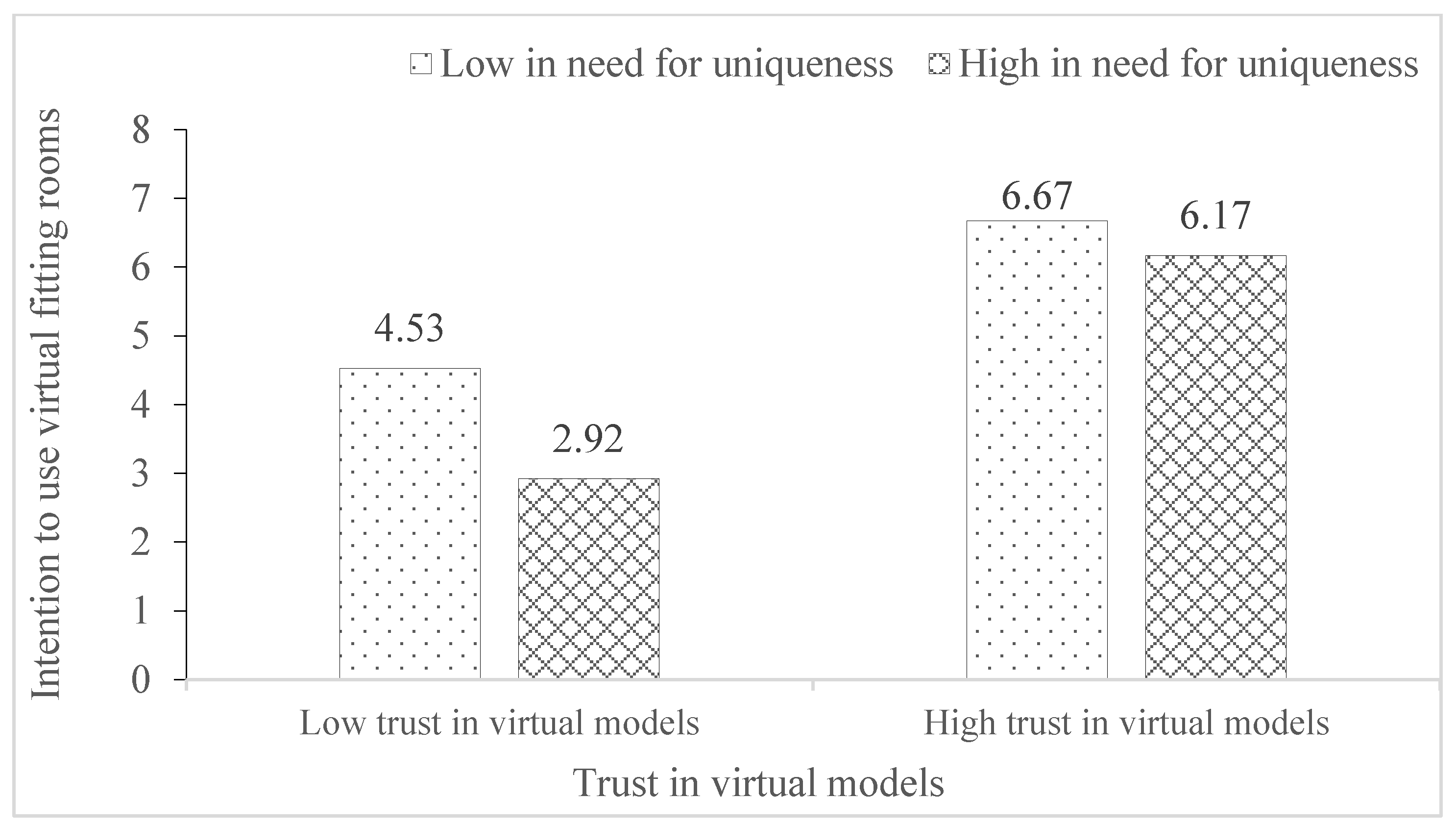

4.5. Trust in Virtual Models, Need for Uniqueness, and Consumers’ Intention to Use Virtual Fitting Rooms

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Aagerup, U., & Scharf, E. R. (2018). Obese models’ effect on fashion brand attractiveness. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 22(4), 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allimamy, S., Deans, K. R., & Gnoth, J. (2019). The effect of co-creation through exposure to augmented reality on customer perceived risk, trust and purchase intent—An empirical analysis. International Journal of Technology and Human Interaction, 7, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Antioco, M., Smeesters, D., & Le Boedec, A. (2012). Take your pick: Kate Moss or the girl next door? The effectiveness of cosmetics advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 52(1), 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argo, J. J., & Dahl, D. W. (2017). Standards of beauty: The impact of mannequins in the retail context. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(5), 974–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(2), 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair, A., Steele, J. R., & Mills, J. S. (2014). Do these norms make me look fat? The effect of exposure to others’ body preferences on personal body ideals. Body Image, 11(3), 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, X., & Wang, K. Y. (2015). Are size-zero female models always more effective than average-sized ones? Depends on brand and self-esteem. European Journal of Marketing, 49(7/8), 1184–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, H., & Akram, S. (2007). Age is no barrier to wanting to look good: Women on body image, age and advertising. Qualitative Market Research, 10(3), 310–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmicheal, K. (2021). How to use cart abandonment emails to win back customers. Available online: https://blog.hubspot.com/ecommerce/shopping-cart-abandonment-reasons-solutions (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Cheema, A., & Kaikati, A. M. (2010). The effect of need for uniqueness on word of mouth. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(3), 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, D. W., Argo, J. J., & Morales, A. C. (2011). Social information in the retail environment: The importance of consumption alignment, referent identity, and self-esteem. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(5), 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lenne, O., Vandenbosch, L., Smits, T., & Eggermont, S. (2021). Framing real beauty: A framing approach to the effects of beauty advertisements on body image and advertising effectiveness. Body Image, 37, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimoka, A., Hong, Y., & Pavlou, P. A. (2012). On product uncertainty in online markets: Theory and evidence. MIS Quarterly, 36(2), 395–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmar, H., & Howard, S. (2004). Professional hazards? The impact of models’ body size on advertising effectiveness and women’s body-focused anxiety in professions that do and do not emphasize the cultural ideal of thinness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 43(4), 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, S., Ranganathan, C., & Sankaranarayanan, B. (2004). Visualization strategies and tools for enhancing customer relationship management. Communications of the ACM, 47(11), 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research. (2021). Virtual fitting room market size, share and trends analysis report by component (hardware, software, services), by application (apparel, beauty and cosmetic), by end-use, by region, and segment forecasts, 2021–2028. Available online: https://www.marketresearch.com/Grand-View-Research-v4060/Virtual-Fitting-Room-Size-Share-14317326/ (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Gursoy, D., Chi, O. H., Lu, L., & Nunkoo, R. (2019). Consumers acceptance of artificially intelligent (AI) device use in service delivery. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gültepe, U., & Güdükbay, U. (2014). Real-time virtual fitting with body measurement and motion smoothing. Computers and Graphics, 43(1), 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, E., & Dittmar, H. (2004). Does size matter? The impact of model’s body size on women’s body-focused anxiety and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(1), 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häubl, G., & Figueroa, P. (2002, April 20–25). Interactive 3D presentations and buyer behavior. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI-02), Minneapolis, MN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Holsen, I., Kraft, P., & Røysamb, E. (2001). The relationship between body image and depressed mood in adolescence: A 5-year longitudinal panel study. Journal of Health Psychology, 6(6), 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C. L., Lu, H. P., & Hsu, H. H. (2007). Adoption of the mobile Internet: An empirical study of multimedia message service (MMS). Omega, 35(6), 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhoff, R., & Lamberty, P. K. (2017). Too special to be duped: Need for uniqueness motivates conspiracy beliefs. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javornik, A., Marder, B., Pizzetti, M., & Warlop, L. (2021). Augmented self—The effects of virtual face augmentation on consumers’ self-concept. Journal of Business Research, 130, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelaar, P. E., Willems, A. G. J., Linssen, L., & Anschutz, D. (2014). A few more ounces? Preference for regular-size models in advertising. Journal of Euromarketing, 22, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Forsythe, S. (2008). Adoption of virtual try-on technology for online apparel shopping. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 22(2), 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H., Kim, M., Park, M., & Yoo, J. (2021). How interactivity and vividness influence consumer virtual reality shopping experience: The mediating role of telepresence. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 15(3), 502–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., & Lennon, S. (2008). The effects of visual and verbal information on attitudes and purchase intentions in internet shopping. Psychology and Marketing, 25(2), 146–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., & Xu, Y. (2018). Classification of virtual fitting room technologies in the fashion industry: From the perspective of consumer experience. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 13(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Xu, Y., & Li, A. (2020a). Technology visibility and consumer adoption of virtual fitting rooms (VFRs): A cross-cultural comparison of Chinese and Korean consumers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 24(2), 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Xu, Y., & Porterfield, A. (2020b). Consumers’ adoption of AR-based virtual fitting rooms: From the perspective of theory of interactive media effects. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 25(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. D., & See, K. A. (2004). Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 46(1), 50–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H., Daugherty, T., & Biocca, F. (2002). Impact of 3D Advertising on product knowledge, brand attitude, and purchase intention: The mediating role of presence. Journal of Advertising, 31(3), 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey-Hall, K. K., Jaramillo, S., Baker, T. L., & Arnold, F. M. (2021). Authenticity, rapport and interactional justice in frontline service: The moderating role of need for uniqueness. Journal of Service Marketing, 35(3), 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C., & Tse, C. H. (2021). Which model looks most like me? Explicating the impact of body image advertisements on female consumer well-being and consumption behaviour across brand categories. International Journal of Advertising, 40(4), 602–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C., Tse, C. H., & Lwin, M. O. (2019). “Average-sized” models do sell, but what about in east Asia? A cross-cultural investigation of US and Singaporean women. Journal of Advertising, 48(5), 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, C. N., & Markey, P. M. (2005). Relations between body image and dieting behaviors: An examination of gender differences. Sex Roles, 53(7), 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B. A. S., Veer, E., & Pervan, S. J. (2007). Self-referencing and consumer evaluations of larger-sized female models: A weight locus of control perspective. Marketing Letters, 18(3), 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B. A. S., & Xavier, R. (2010). How do consumers react to physically larger models? Effects of model body size, weight control beliefs and product type on evaluations and body perceptions. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 18(6), 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mendelson, M. J., Mendelson, B. K., & Andrews, J. (2000). Self-esteem, body esteem, and body-mass in late adolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21(3), 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merle, A., Senecal, S., & St-Onge, A. (2012). Whether and how virtual try-on influences consumer responses to an apparel web site. International Journal Electronic Commerce, 16(3), 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Waarden, L., & Cloarec, J. (2022). “Baby, you can drive my car”: Psychological antecedents that drive consumers’ adoption of AI-powered autonomous vehicles. Technovation, 109, 102348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Domínguez, S., Servián-Franco, F., del Paso, G. A. R., & Cepeda-Benito, A. (2018). Images of thin and plus-size models produce opposite effects on women’s body image, body dissatisfaction, and anxiety. Sex Roles, 80(9), 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K. B., & Häubl, G. (2008). Interactive consumer decision aids. In B. Wierenga (Ed.), Handbook of marketing decision models (pp. 55–77). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2024). 2023, the total online retail sales increased by 11% to 15.42 trillion yuan. Available online: http://tradeinservices.mofcom.gov.cn/article/yanjiu/hangyezk/202401/160763.html (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Ohanian, R. (1991). The impact of celebrity spokespersons’ perceived image on consumers’ intention to purchase. Journal of Advertising Research, 31(1), 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, A. B., Bilgihan, A., Nusair, K., & Okumus, F. (2016). What keeps the mobile hotel booking users loyal? Investigating the roles of self-efficacy, compatibility, perceived ease of use, and perceived convenience. International Journal of Information Management, 36(6), 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. (2020). Multifaceted trust in tourism service robots. Annals of Tourism Research, 81, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J., & Loken, B. (2004). When will larger-sized female models in advertisements be viewed positively? The moderating effects of instructional frame, gender, and need for cognition. Psychology and Marketing, 21(6), 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, A. C., & Brison, N. T. (2019). Lose like a man: Body image and celebrity endorsement effects of weight loss product purchase intentions. International Journal of Advertising, 38(8), 1098–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J. L., Matacin, M. L., & Stuart, A. E. (2001). Body esteem: An exception to self-enhancing illusions? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(9), 1951–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschnabel, P. A. (2021). Augmented reality is eating the real-world! The substitution of physical products by holograms. International Journal of Information Management, 57, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Y., & Marshall, P. (2017). Research in the wild. Synthesis Lectures on HumanCentered Informatics, 10(3), 1–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, J. A., Garbarino, E. C., & Malter, A. J. (2006). Keeping the body in mind: The influence of body esteem and body boundary aberration on consumer beliefs and purchase intentions. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(1), 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, S. (2020). When more pain is better: Role of need for uniqueness in service evaluations of observable service recovery. International Journal of Information Management, 85, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S. I., & Lee, Y. (2011). Consumer’s perceived risk reduction by 3D virtual model. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 39(12), 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoenberger, H., Kim, E. A., & Johnson, E. K. (2019). # BeingReal about instagram ad models: The effects of perceived authenticity: How image modification of female body size alters advertising attitude and buying intention. Journal of Advertising Research, 60(2), 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2024). E-commerce worldwide-statistics & facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/871/online-shopping/#topicOverview (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Tan, Y. C., Chandukala, S. R., & Reddy, S. K. (2022). Augmented reality in retail and its impact on sales. Journal of Marketing, 86(1), 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K. T., Bearden, W. O., & Hunter, G. L. (2001). Consumers’ need for uniqueness: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(1), 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M., & Lynch, J. E. (2001). Body image across the life span in adult women: The role of self-objectification. Developmental Psychology, 37(2), 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifts, V., & Häubl, G. (2003). Information availability and consumer preference: Can online retailers benefit from providing access to competitor price information. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(1&2), 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I. P., Zach, F. J., & Wang, J. (2020). Do travelers trust intelligent service robots? Annals of Tourism Research, 81, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., & Xiong, G. (2019). Try it on! Contingency effects of virtual fitting rooms. Journal of Management Information Systems, 36(3), 789–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., Xiong, G., Mao, H., & Ma, M. (2023). Virtual fitting room effect: Moderating role of body mass index. Journal of Marketing Research, 60(6), 1221–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S., & Shin, K. (2019). Body esteem among Korean adolescent boys and girls. Sustainability, 11(7), 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Tao, D., Qu, X., Zhang, X., Lin, R., & Zhang, W. (2019). The roles of initial trust and perceived risk in public’s acceptance of automated vehicles. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 98, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Items | Factor Loadings (T Value) | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Esteem | BE1 | 0.80 (19.63) | 0.910 | 0.912 | 0.675 |

| BE2 | 0.81 (19.75) | ||||

| BE3 | 0.88 (22.56) | ||||

| BE4 | 0.87 (22.12) | ||||

| BE5 | 0.75 (17.79) | ||||

| Preference for thin models | PR1 | 0.82 (20.15) | 0.912 | 0.912 | 0.676 |

| PR2 | 0.84 (21.01) | ||||

| PR3 | 0.79 (19.14) | ||||

| PR4 | 0.81 (20.03) | ||||

| PR5 | 0.85 (21.25) | ||||

| Trust in virtual models | TR1 | 0.79 (19.06) | 0.888 | 0.892 | 0.676 |

| TR2 | 0.77 (18.37) | ||||

| TR3 | 0.89 (22.82) | ||||

| TR4 | 0.84 (21.05) | ||||

| Need for uniqueness | NE1 | 0.66 (16.63) | 0.808 | 0.858 | 0.605 |

| NE2 | 0.87 (21.50) | ||||

| NE3 | 0.71 (17.49) | ||||

| NE4 | 0.87 (21.37) | ||||

| Intention to use virtual fitting rooms | IN1 | 0.82 (19.88) | 0.864 | 0.862 | 0.677 |

| IN2 | 0.84 (20.56) | ||||

| IN3 | 0.81 (19.69) |

| BE | PR | TR | NE | IN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE | 0.821 | ||||

| PR | 0.11 | 0.822 | |||

| TR | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.822 | ||

| NE | 0.30 | 0.49 | 0.30 | 0.778 | |

| IN | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.67 | 0.06 | 0.823 |

| Congruency | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant Body Esteem | Participants Selected Virtual Models with a Body Size That Was Congruent with Their Own Body Size | Participants Selected Virtual Models with a Body Size That Was Thinner Than Their Own | Participants Selected Virtual Models with a Body Size That Was Larger Than Their Own |

| High | 37 | 20 | 5 |

| Medium | 192 | 53 | 60 |

| Low | 15 | 5 | 45 |

| Hypotheses | Result |

|---|---|

| H1: Consumer’s body esteem significantly influences their selection of virtual models. To be specific, for consumers with high body esteem, they select a virtual model with a body size that is consistent with their own; for consumers with low body esteem, they prefer large-size virtual models. | Supported |

| H2: Body esteem significantly influences on their trust in virtual models. To be specific, for consumers with high body esteem, they are more likely to trust a virtual model with a body size that is consistent with their own; for consumers with low body esteem, they are more likely to trust a large-sized virtual model. | Supported |

| H3: Preference for thin models moderates the effect of body esteem on trust in models. Specifically, for consumers who have strong preference for thin models, the difference between high body esteem and low body esteem on trust in virtual models will be attenuated; for consumers who have weak preference for thin models, the different effect between high body esteem and low body esteem on trust in virtual models remains unchanged. | Supported |

| H4: Trust in virtual models mediates the influence of body esteem on consumer’s intention to use virtual fitting rooms. | |

| H5: Need for uniqueness moderates the effect of trust in virtual models on intention to use virtual fitting rooms. Specially, for consumers high in need for uniqueness, the enhancement effect of trust in virtual models on intention to use virtual fitting rooms will be attenuated; for consumers low in need for uniqueness, the enhancement effect remains unchanged. | Partially supported, for consumers high in need for uniqueness, the enhancement effect of trust in virtual models was not attenuated. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, R.; Jin, H. How Body Esteem Influences Virtual Model Selection and Intention to Use Virtual Fitting Rooms. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1526. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111526

Wu R, Jin H. How Body Esteem Influences Virtual Model Selection and Intention to Use Virtual Fitting Rooms. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1526. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111526

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Ruijuan, and Huizhen Jin. 2025. "How Body Esteem Influences Virtual Model Selection and Intention to Use Virtual Fitting Rooms" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1526. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111526

APA StyleWu, R., & Jin, H. (2025). How Body Esteem Influences Virtual Model Selection and Intention to Use Virtual Fitting Rooms. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1526. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111526