Two Sides of the Same Quip: Humor Appeals Can Indirectly Reduce Reactance via Perceived Humor but Simultaneously Increase Reactance Independently of Perceived Humor

Abstract

1. Introduction

If something is ridiculous, how can it be threatening?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Design and Procedures

2.3. Experimental Materials

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Perceived Threat to Freedom

2.4.2. Perceived Humor

2.4.3. State Reactance

2.4.4. Attitude

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDC | Centers of Disease Control and Prevention |

| FTL | Freedom threatening language |

| 1 | Given prior research about order effects of humor and risk information on reactance (Kim et al., 2024), the order of the freedom threatening language and humor appeal manipulation was counterbalanced randomly to offset potential order effects of the two manipulations. This variable did not demonstrate any significant main effects, nor did it interact with the experimental variables to predict any dependent variables—meaning order effects did not occur in this study—but we controlled for order in our analyses given its role in the study’s design. Substantive results were meaningfully equivalent regardless of whether this variable was entered as a covariate. |

| 2 | Results reported do not include vaccination status (i.e., no dose vs. one dose of a two-dose sequence) as a covariate given that this variable was balanced via random assignment procedures. However, results were meaningfully equivalent in models that included vaccination status as a covariate. |

References

- Armstrong, K., Richards, A. S., & Boyd, K. J. (2021). Red-hot reactance: Color cues moderate the freedom threatening characteristics of health PSAs. Health Communication, 36(6), 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessarabova, E., Fink, E. L., & Turner, M. (2013). Reactance, restoration, and cognitive structure: Comparative statics. Human Communication Research, 39(3), 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessarabova, E., Miller, C. H., & Russell, J. (2017). A further exploration of the effects of restoration postscripts on reactance. Western Journal of Communication, 81(3), 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C., Schmid-Küpke, N. K., Otten, L., & von Hirschhausen, E. (2020). Increasing the willingness to participate in organ donation through humorous health communication: (Quasi-) experimental evidence. PLoS ONE, 15(11), e0241208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bippus, A. M., Dunbar, N. E., & Liu, S. J. (2012). Humorous responses to interpersonal complaints: Effects of humor style and nonverbal expression. The Journal of Psychology, 146(4), 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsen, T., & Palm, R. (2022). Politicization and COVID-19 vaccine resistance in the US. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, 188(1), 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brehm, S. S., & Brehm, J. W. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burgoon, M., Alvaro, E., Grandpre, J., & Voloudakis, M. (2002). Revisiting the theory of psychological reactance: Communicating threats to attitudinal freedom. In J. P. Dillard, & M. Pfau (Eds.), The persuasion handbook: Developments in theory and practice (pp. 213–232). Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünzli, F., Dillard, J. P., Li, Y., & Eppler, M. J. (2025). When visual communication backfires: Reactance to three aspects of imagery. Communication Research, 52(5), 683–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, R. B. (2022). On the psychophysiological and defensive nature of psychological reactance theory. Journal of Communication, 72(4), 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, R. B., Compton, J., Reynolds-Tylus, T., Neumann, D., & Park, J. (2023). Revisiting the effects of an inoculation treatment on psychological reactance: A conceptual replication and extension with self-report and psychophysiological measures. Human Communication Research, 49(1), 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, J. P., & Shen, L. (2005). On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Communication Monographs, 72(2), 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M. (2009). A meta-analysis of humor in advertising. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(2), 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisend, M. (2011). How humor in advertising works: A meta-analytic test of alternative models. Marketing Letters, 22(2), 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, L., Monahan, K., & Berger, C. (1999). A laughing matter? The uses of humor in medical interactions. Motivation and Emotion, 23(2), 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruner, C. R. (1985). Advice to the beginning speaker on using humor—What the research tells us. Communication Education, 34(2), 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H., Yoon, H. J., Han, J. Y., Seo, J. K., & Ko, Y. (2024). The order effects of humor and risk messaging strategies in public service advertisements: The moderating role of trust in science and mediating role of psychological reactance. International Journal of Advertising, 44(5), 925–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriss, L. A., Quick, B. L., Rains, S. A., & Barbati, J. L. (2022). Psychological reactance theory and COVID-19 vaccine mandates: The roles of threat magnitude and direction of threat. Journal of Health Communication, 27(9), 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Shi, J. (2025). Message effects on psychological reactance: Meta-analyses. Human Communication Research, hqaf016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, S., De Figueiredo, A., Piatek, S. J., De Graaf, K., & Larson, H. J. (2021). Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(3), 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F., & Sun, Y. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: The effects of combining direct and indirect online opinion cues on psychological reactance to health campaigns. Computers in Human Behavior, 127, 107057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, R., Ma, Z., Kalny, C. S., & Walter, N. (2025). Words that trigger: A meta-analysis of threatening language, reactance, and persuasion in health. Journal of Communication, jqaf004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1989). Bipolar scales. In P. Emmert, & L. L. Barker (Eds.), Measurement of communication behavior (pp. 154–167). Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. C. (2000). Humor as a double-edged sword: Four functions of humor in communication. Communication Theory, 10(3), 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C. H., Lane, L. T., Deatrick, L. M., Young, A. M., & Potts, K. A. (2007). Psychological reactance and promotional health messages: The effects of controlling language, lexical concreteness, and the restoration of freedom. Human Communication Research, 33(2), 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer-Gusé, E., Robinson, M. J., & Mcknight, J. (2018). The role of humor in messaging about the MMR vaccine. Journal of Health Communication, 23(6), 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R. L., Moyer-Gusé, E., & Byrne, S. (2007). All joking aside: A serious investigation into the persuasive effect of funny social issue messages. Communication Monographs, 74(1), 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, B. L., & Considine, J. R. (2008). Examining the use of forceful language when designing exercise persuasive messages for adults: A test of conceptualizing reactance arousal as a two-step process. Health Communication, 23(5), 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quick, B. L., Kam, J. A., Morgan, S. E., Montero Liberona, C. A., & Smith, R. A. (2015). Prospect theory, discrete emotions, and freedom threats: An extension of psychological reactance theory. Journal of Communication, 65(1), 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, B. L., Shen, L., & Dillard, J. P. (2013). Reactance theory. In J. P. Dillard, & L. Shen (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of persuasion (pp. 167–183). Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliff, C. L. (2021). Characterizing reactance in communication research: A review of conceptual and operational approaches. Communication Research, 48(7), 1033–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A. S., & Banas, J. A. (2015). Inoculating against reactance to persuasive health messages. Health Communication, 30(5), 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, A. S., Banas, J. A., & Magid, Y. (2017). More on inoculating against reactance to persuasive health messages: The paradox of threat. Health Communication, 32(7), 890–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, A. S., Bessarabova, E., Banas, J. A., & Bernard, D. R. (2022). Reducing psychological reactance to health promotion messages: Comparing preemptive and postscript mitigation strategies. Health Communication, 37(3), 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, A. S., Bessarabova, E., Banas, J. A., & Larsen, M. (2021). Freedom-prompting reactance mitigation strategies function differently across levels of trait reactance. Communication Quarterly, 69(3), 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L. (2010). Mitigating psychological reactance: The role of message-induced empathy in persuasion. Human Communication Research, 36(3), 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L. (2011). The effectiveness of empathy-versus fear-arousing antismoking PSAs. Health Communication, 26(5), 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalski, P., Tamborini, R., Glazer, E., & Smith, S. (2009). Effects of humor on presence and recall of persuasive messages. Communication Quarterly, 57(2), 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strick, M., Holland, R. W., Van Baaren, R. B., & Van Knippenberg, A. (2012). Those who laugh are defenseless: How humor breaks resistance to influence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18(2), 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The pandemic’s true death toll . (2022, October). The Economist. Available online: https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/coronavirus-excess-deaths-estimates (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Vaala, S. E., Ritter, M. B., & Palakshappa, D. (2022). Experimental effects of Tweets encouraging social distancing: Effects of source, emotional appeal, and political ideology on emotion, threat, and efficacy. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 28(2), E586–E594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, N., Cody, M. J., Xu, L. Z., & Murphy, S. T. (2018). A priest, a rabbi, and a minister walk into a bar: A meta-analysis of humor effects on persuasion. Human Communication Research, 44(4), 343–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., & Yu, S. (2022). Using humor to promote social distancing on Tiktok during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 887744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H. J., Lee, J., Han, J. Y., Ko, Y., Kim, H., Seo, Y., & Seo, J. K. (2023). Using humor to increase COVID-19 vaccination intention for the unvaccinated: The moderating role of trust in government. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 22(5), 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D. G. (2008). The privileged role of the late-night joke: Exploring humor’s role in disrupting argument scrutiny. Media Psychology, 11(1), 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S., & Lu, H. (2022). Examining a conceptual framework of aggressive and humorous styles in science YouTube videos about climate change and vaccination. Public Understanding of Science, 31(7), 921–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Perceived Freedom Threat | Perceived Humor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p | ||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||

| FTL a | 0.94 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 10.50 | .001 | −0.18 | 0.35 | −0.87 | 0.50 | .60 |

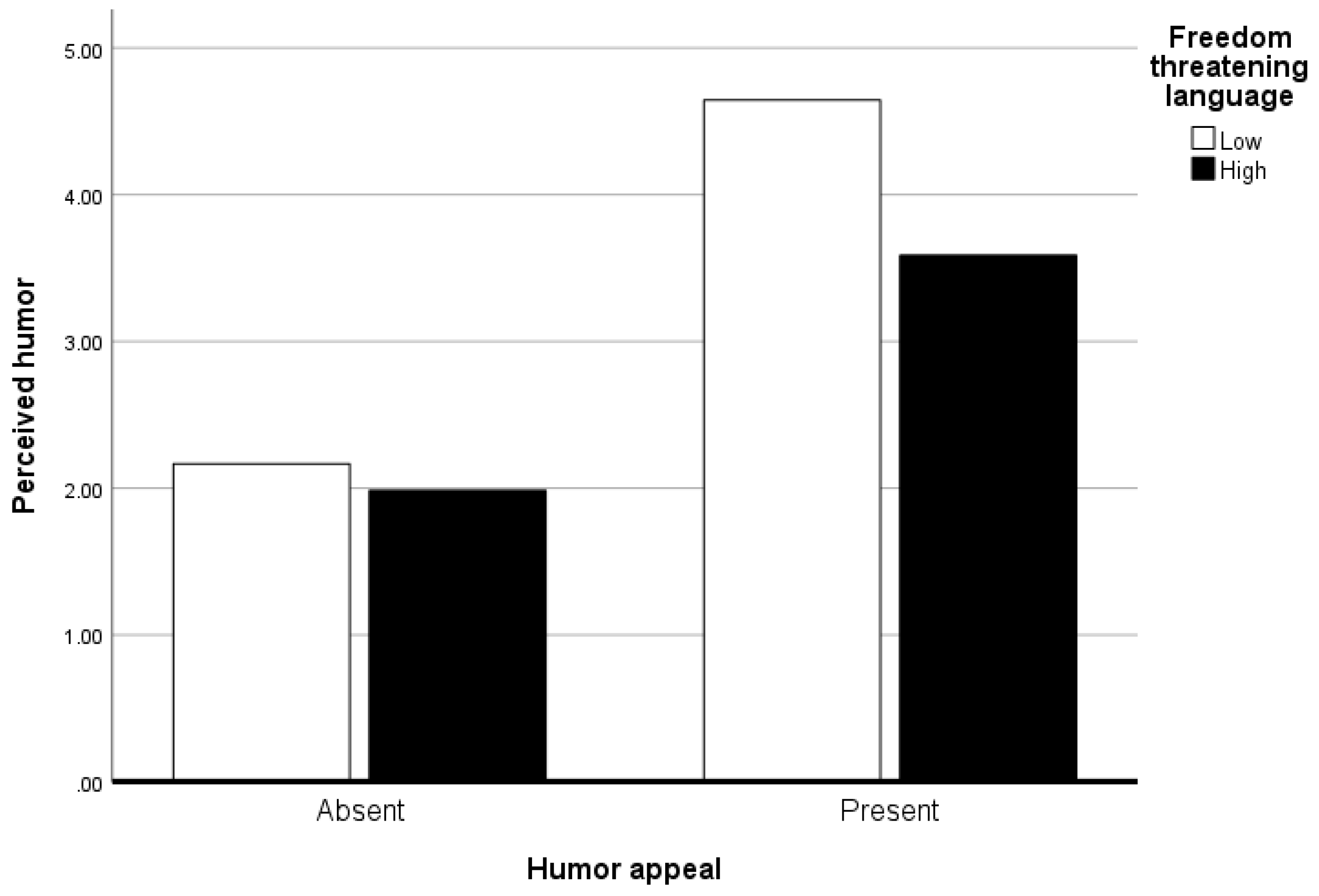

| Humor appeal b | 0.01 | 0.30 | −0.58 | 0.59 | .99 | 2.48 | 0.36 | 1.76 | 3.20 | .000 |

| FTL × Humor appeal | −0.12 | 0.41 | −0.94 | 0.70 | .77 | −0.88 | 0.51 | −0.188 | 0.13 | .08 |

| Order c | 0.00 | 0.21 | −0.41 | 0.41 | .99 | 0.18 | 0.26 | −0.32 | 0.68 | .48 |

| Effect | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| Perceived freedom threat | 0.47 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.53 | .000 |

| Perceived humor | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.25 | −0.01 | .01 |

| FTL a | 0.01 | 0.13 | −0.25 | 0.27 | .93 |

| Humor appeal b | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.63 | .03 |

| FTL × Humor appeal | −0.28 | 0.19 | −0.65 | 0.10 | .14 |

| Order c | −0.10 | 0.09 | −0.29 | 0.08 | .27 |

| Effect | Estimate | SE | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| State reactance | −0.54 | 0.14 | −0.82 | −0.26 | .000 |

| Perceived freedom threat | −0.15 | 0.09 | −0.34 | 0.03 | .10 |

| Perceived humor | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.12 | 0.09 | .82 |

| FTL a | 0.08 | 0.25 | −0.42 | 0.59 | .74 |

| Humor appeal b | 0.52 | 0.30 | −0.07 | 10.11 | .09 |

| FTL × Humor appeal | −0.18 | 0.37 | −0.92 | 0.58 | .63 |

| Order c | 0.13 | 0.18 | −0.24 | 0.49 | .50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Richards, A.S.; Curcio, N.S.; Hall, S.G. Two Sides of the Same Quip: Humor Appeals Can Indirectly Reduce Reactance via Perceived Humor but Simultaneously Increase Reactance Independently of Perceived Humor. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1509. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111509

Richards AS, Curcio NS, Hall SG. Two Sides of the Same Quip: Humor Appeals Can Indirectly Reduce Reactance via Perceived Humor but Simultaneously Increase Reactance Independently of Perceived Humor. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1509. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111509

Chicago/Turabian StyleRichards, Adam S., Nicholas S. Curcio, and Sydney G. Hall. 2025. "Two Sides of the Same Quip: Humor Appeals Can Indirectly Reduce Reactance via Perceived Humor but Simultaneously Increase Reactance Independently of Perceived Humor" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1509. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111509

APA StyleRichards, A. S., Curcio, N. S., & Hall, S. G. (2025). Two Sides of the Same Quip: Humor Appeals Can Indirectly Reduce Reactance via Perceived Humor but Simultaneously Increase Reactance Independently of Perceived Humor. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1509. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111509