The Relationship Between Academic Delay of Gratification and Depressive Symptoms Among College Students: Exploring the Roles of Academic Involution and Academic Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Hypothesis

2.1. Academic Delay of Gratification and Depressive Symptoms

2.2. The Suppression Role of Academic Involution

2.3. The Moderating Role of Academic Resilience

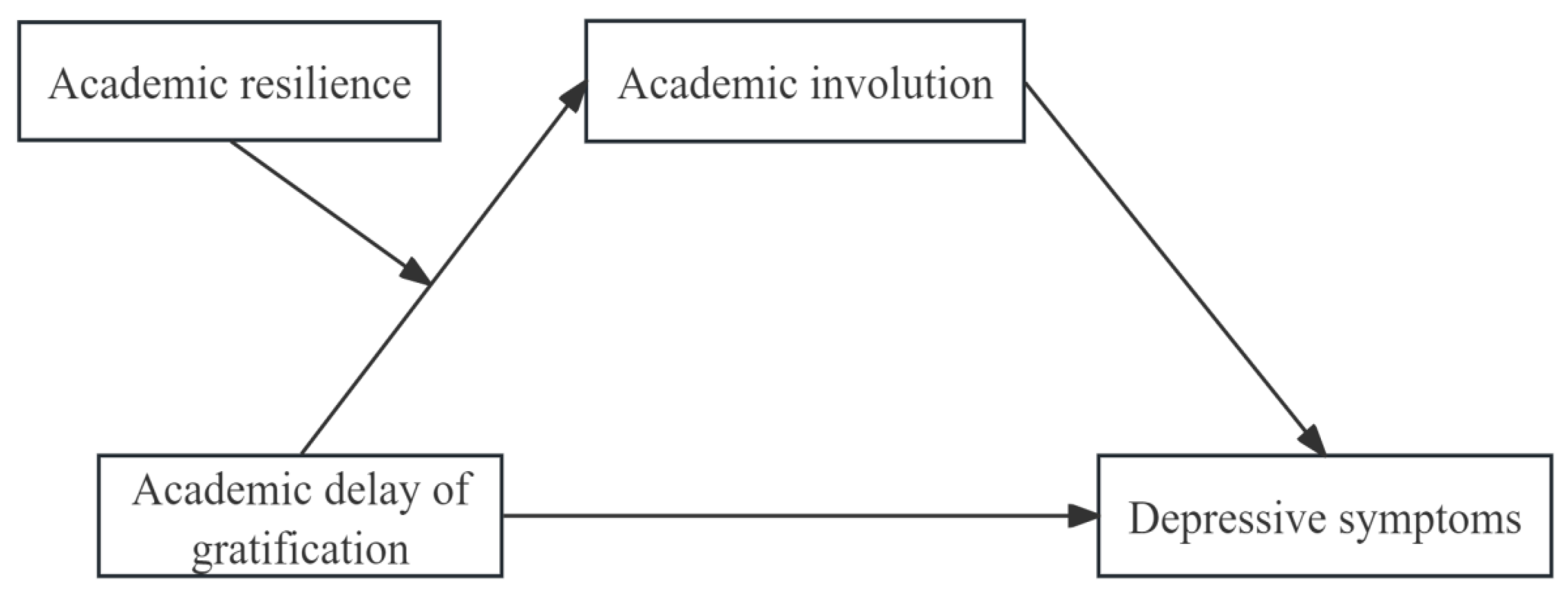

2.4. The Present Study

3. Methods

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Academic Delay of Gratification

3.2.2. Academic Involution

3.2.3. Academic Resilience

3.2.4. Depressive Symptoms

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias Test

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

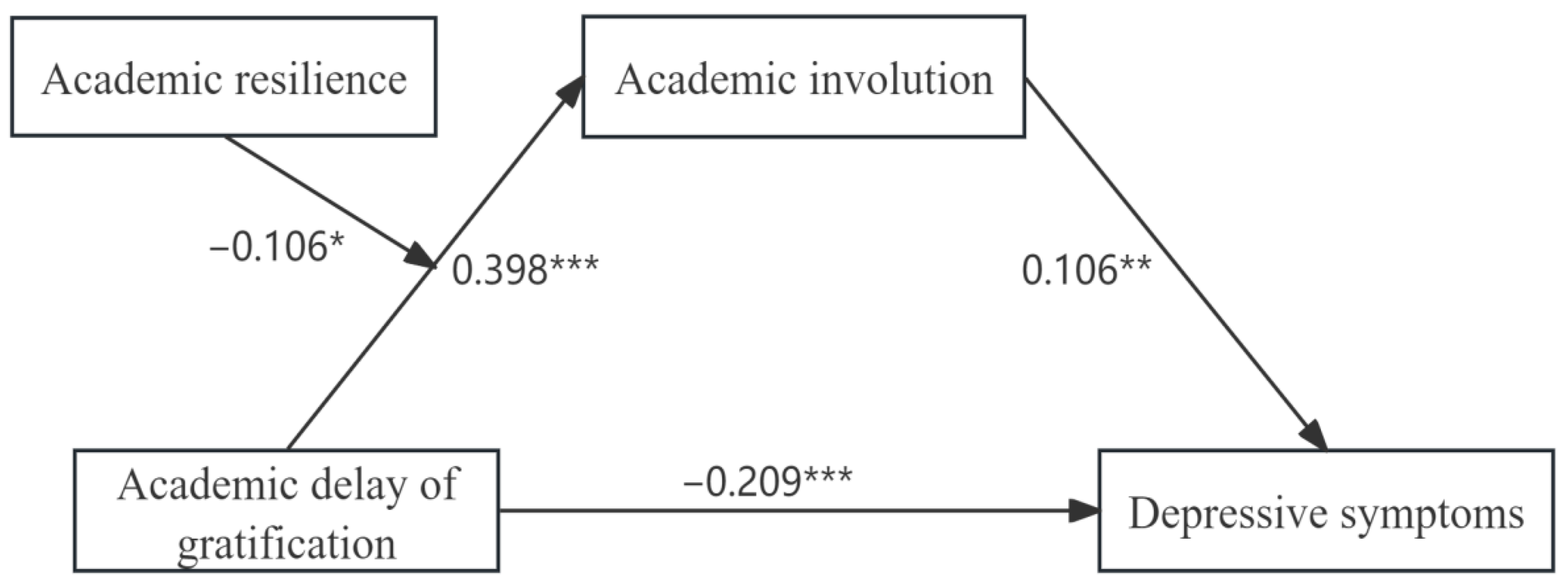

4.3. Testing for Mediation Effect

4.4. Moderated Mediation Effect Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. The Relationship Between Academic Delay of Gratification and Depressive Symptoms

5.2. The Suppression Effect of Academic Involution

5.3. The Moderating Effect of Academic Resilience

5.4. Research Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aloufi, M. A., Jarden, R. J., Gerdtz, M. F., & Kapp, S. (2021). Reducing stress, anxiety and depression in undergraduate nursing students: Systematic review. Nurse Education Today, 102, 104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, B., & Pande, N. (2016). Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembenutty, H. (1999). Sustaining motivation and academic goals: The role of academic delay of gratification. Learning and Individual Differences, 11(3), 233–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembenutty, H. (2007). Self-regulation of learning and academic delay of gratification: Gender and ethnic differences among college students. Journal of Advanced Academics, 18(4), 586–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembenutty, H. (2011). Academic delay of gratification and academic achievement. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 126, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembenutty, H., & Karabenick, S. A. (1998). Academic delay of gratification. Learning and Individual Differences, 10(4), 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bembenutty, H., & Karabenick, S. A. (2004). Inherent association between academic delay of gratification, future time perspective, and self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 16, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogg, T., & Roberts, B. W. (2004). Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin, 130(6), 887–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownson, C., Boyer, B. P., Runyon, C., Boynton, A. E., Jonietz, E., Spear, B. I., Irvin, S. A., Christman, S. K., Balsan, M. J., & Drum, D. J. (2024). Focusing resources to promote student well-being: Associations of malleable psychosocial factors with college academic performance and distress and suicidality. Higher Education, 88(1), 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukcan-Tetik, A., Finkenauer, C., & Bleidorn, W. (2018). Within-person variations and between-person differences in self-control and wellbeing. Personality and Individual Differences, 122, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A., Houts, R. M., Belsky, D. W., Goldman-Mellor, S. J., Harrington, H., Israel, S., Meier, M. H., Ramrakha, S., Shalev, I., Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2014). The p factor: One general psychopathology factor in the structure of psychiatric disorders? Clinical Psychological Science, 2(2), 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, S. (2016). The Academic Resilience Scale (ARS-30): A new multidimensional construct measure. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L., & Yeung, W. J. J. (2025). Delayed gratification predicts behavioral and academic outcomes: Examining the validity of the delay-of-gratification choice paradigm in Singaporean young children. Applied Developmental Science, 29(2), 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q., & Lee, B. G. (2023). Deep learning models for stress analysis in university students: A sudoku-based study. Sensors, 23(13), 6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V., & Catling, J. (2015). The role of resilience, delayed gratification and stress in predicting academic performance. Psychology Teaching Review, 21(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deary, I. J., Batty, G. D., Pattie, A., & Gale, C. R. (2008). More intelligent, more dependable children live longer: A 55-year longitudinal study of a representative sample of the Scottish nation. Psychological Science, 19(9), 874–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, H., O’Hara, M., Cook, A., & Mantzios, M. (2021). Mindfulness, self-compassion, resiliency and wellbeing in higher education: A recipe to increase academic performance. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(3), 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J., Zhao, Y., Feng, X., Wang, Y., Yu, Z., Hua, L., Wang, S., & Li, J. (2021). How is fatalistic determinism linked to depression? The mediating role of self-control and resilience. Personality and Individual Differences, 180, 110992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X. L., Zhang, K., Chen, X. F., & Chen, Z. (2023). Mental health blue book: China national mental health development report (2021–2022). Social Sciences Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Funder, D. C. (1998). On the pros and cons of delay of gratification. Psychological Inquiry, 9(3), 211–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funder, D. C., & Block, J. (1989). The role of ego-control, ego-resiliency, and IQ in delay of gratification in adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furnham, A., & Cheng, H. (2019). The Big-Five personality factors, mental health, and social-demographic indicators as independent predictors of gratification delay. Personality and Individual Differences, 150, 109533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, C. (1963). Agricultural involution: The processes of ecological change in Indonesia (p. 176). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, W., Demanins, S. A., Bureau, J. S., Guay, F., & Morin, A. J. (2023). On the nature, predictors, and outcomes of undergraduate students’ psychological distress profiles. Learning and Individual Differences, 108, 102378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenweiser, A. A. (1913). The principle of limited possibilities in the development of culture. The Journal of American Folklore, 26(101), 259–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X., Xie, X. Y., Xu, R., & Luo, Y. J. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Chinese versions of DASS-21 in Chinese college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 18(4), 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, P. A., Hurst, A., Johnson, J., & Tarrier, N. (2012). Psychological resilience in young and older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(3), 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grineski, S. E., Morales, D. X., Collins, T. W., Nadybal, S., & Trego, S. (2021). Anxiety and depression among US college students engaging in undergraduate research during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of American College Health, 72(1), 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., Wang, J., Li, N., & Wang, L. (2025). The impact of teacher emotional support on learning engagement among college students mediated by academic self-efficacy and academic resilience. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürcan-Yıldırım, D., & Gençöz, T. (2022). The association of self-discrepancy with depression and anxiety: Moderator roles of emotion regulation and resilience. Current Psychology, 41(4), 1821–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, H., Dang, H. M., Odum, A. L., DeHart, W. B., & Weiss, B. (2023). Sooner is better: Longitudinal relations between delay discounting, and depression and anxiety symptoms among Vietnamese adolescents. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 51(1), 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, P. E., Ducker, I., Gooding, R., James, M., & Rutter-Eley, E. (2020). Anxiety and depression in a sample of UK college students: A study of prevalence, comorbidity, and quality of life. Journal of American College Health, 69(8), 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S., Ren, Q., Jiang, C., & Wang, L. (2021). Academic stress and depression of Chinese adolescents in junior high schools: Moderated mediation model of school burnout and self-esteem. Journal of Affective Disorders, 295, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, N., Nallapati, A., Machado, M. X., Nair, V., Matele, S., Muthusamy, N., & Sinha, A. (2020). Assessment of academic stress and its coping mechanisms among medical undergraduate students in a large Midwestern university. Current Psychology, 40, 2599–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamtsios, S., & Karagiannopoulou, E. (2013). Conceptualizing students’ academic hardiness dimensions: A qualitative study. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(3), 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. B., & Du, H. (2011). All good things come to those who wait: Validating the Chinese version of the academic delay of gratification scale (ADOGS). The International Journal of Educational and Psychological Assessment, 7(1), 64–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. S. H., Wu, Y. J., Chao, E., Chang, C. W., Hwang, K. S., & Wu, W. C. (2021). Resilience as a mediator of interpersonal relationships and depressive symptoms amongst 10th to 12th grade students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 278, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. (2024). The mechanism of self-regulated learning among rural primary middle school students: Academic delay of gratification and resilience. Learning and Motivation, 87, 102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A., Shi, Y., Zhao, Y., & Ni, J. (2024). Influence of academic involution atmosphere on college students’ stress response: The chain mediating effect of relative deprivation and academic involution. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A., Wang, Y., Li, R., Chen, Z., & Ni, J. (2025). Academic involution and mental internal friction of college students: The mediating role of academic stress and the moderating role of rumination. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 34(3), 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Yi, D., & Li, T. (2024). The mediated moderation of conscientiousness and active involution on Zhongyong practical thinking and depression. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 17, 3005–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X. Q., Guo, Y. X., Zhang, W. J., & Gao, W. J. (2022). Influencing factors, prediction and prevention of depression in college students: A literature review. World Journal of Psychiatry, 12(7), 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y., Chen, J., Chen, K., Liu, J., & Wang, W. (2023). The associations between academic stress and depression among college students: A moderated chain mediation model of negative affect, sleep quality, and social support. Acta Psychologica, 239, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Tu, Y., Yang, H., Gao, J., Xu, Y., & Yang, Q. (2022). Have you “involution” today—Competition psychology scale for college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 951931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L., Huang, C., Tao, R., Cui, Z., & Schluter, P. (2021). Meta-analytic review of online guided self-help interventions for depressive symptoms among college students. Internet Interventions, 25, 100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. J., & Marsh, H. W. (2006). Academic resilience and its psychological and educational correlates: A construct validity approach. Psychology in the Schools, 43(3), 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, C., Broeckmans, J., Doumen, S., Groenen, A., & Molenberghs, G. (2014). Do diligent students perform better? Complex relations between student and course characteristics, study time, and academic performance in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 39(4), 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Peake, P. K. (1988). The nature of adolescent competencies predicted by preschool delay of gratification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(4), 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moè, A. (2022). Does the weekly practice of recalling and elaborating episodes raise well-being in university students? Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(7), 3389–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, K. H., & Jiang, J. (2017). Massification of higher education: Challenges for admissions and graduate employment in China. In Managing international connectivity, diversity of learning and changing labour markets: East Asian perspectives (pp. 219–243). Springer Singapore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, C. R., Lee, D. H., Lee, J. Y., Choi, A. R., Chung, S. J., Kim, D.-J., Bhang, S.-Y., Kwon, J.-G., Kweon, Y.-S., & Choi, J.-S. (2018). The role of resilience in internet addiction among adolescents between sexes: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 7(8), 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, C. Y., Chan, C. S., & Tang, K. N. (2021). Delayed gratification and psychosocial wellbeing among high-risk youth in rehabilitation: A latent change score analysis. Applied Developmental Science, 25(3), 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardi, F., & Dartanto, T. (2021). Growth mindset, delayed gratification, and learning outcome: Evidence from a field survey of least-advantaged private schools in Depok-Indonesia. Heliyon, 7(4), e06681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Arbués, E., Gea-Caballero, V., Granada-López, J. M., Juárez-Vela, R., Pellicer-García, B., & Antón-Solanas, I. (2020). The prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress and their associated factors in college students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y., Tang, R., & Li, M. (2022). The relationship between delay of gratification and work engagement: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Heliyon, 8(8), e10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, J. R., & Masten, A. S. (2005). Resilience in context. In R. D. Peters, B. Leadbeater, & R. McMahon (Eds.), Resilience in children, families, and communities: Linking context to practice and policy (pp. 13–25). Kluwer Academic/Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, B. L., & Chen, C. P. (2024). Does delayed gratification come at the cost of work-life conflict and burnout? Current Psychology, 43(2), 1952–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Hu, J., Zhou, Y., Jiang, L., Chen, J., Xi, J., Fang, J., & Zhang, S. (2025). Problematic smartphone usage and inadequate mental health literacy potentially increase the risks of depression, anxiety, and their comorbidity in Chinese college students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 20, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Lei, L., & Qiao, X. (2021). The mediating effects of pursuing pleasure between self-regulatory fatigueand smartphone addiction among undergraduate students: The moderating effects of connectedness to nature. Psychological Development and Education, 37(04), 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Huang, P., Xi, Y., & King, R. B. (2025). Fostering resilience among university students: The role of teaching and learning environments. Higher Education, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. R., Yang, Y., & Cui, T. (2023). Development and validation of an academic involution scale for college students in China. Psychology in the Schools, 61, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. C., & Watson, A. A. (2016). Coping self-efficacy and academic stress among Hispanic first-year college students: The moderating role of emotional intelligence. Journal of College Counseling, 19(3), 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong Aitken, H. G., Rabanal-León, H. C., Saldaña-Bocanegra, J. C., Carranza-Yuncor, N. R., & Rondon-Eusebio, R. F. (2024). Variables linked to academic stress related to the psychological well-Being of college students inside and outside the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 14(7), 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D., Zhang, H., Guo, S., & Zeng, W. (2022). Influence of anxiety on university students’ academic involution behavior during COVID-19 pandemic: Mediating effect of cognitive closure needs. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1005708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y., Peng, Y., Li, W., Lu, S., Wang, C., Chen, S., & Zhong, J. (2023). Psychometric evaluation of the academic involution scale for college students in China: An application of Rasch analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1135658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z., Chi, S., Ma, X., & Pan, L. (2025). The impact of basic psychological needs on academic procrastination: The sequential mediating role of anxiety and self-control. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1576619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Shi, L., Tian, T., Zhou, Z., Peng, X., Shen, Y., Li, Y., & Ou, J. (2022). Associations between academic stress and depressive symptoms mediated by anxiety symptoms and hopelessness among Chinese college students. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Karabenick, S. A., Maruno, S. I., & Lauermann, F. (2011). Academic delay of gratification and children’s study time allocation as a function of proximity to consequential academic goals. Learning and Instruction, 21(1), 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Xiong, W., & Yue, Y. (2024). Involution life in the ivory tower: A Chinese university’s teacher perceptions on academic profession and well-being under the double first-class initiative. Asia Pacific Education Review, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Hsiao, F. C., Shi, X., Yang, J., Huang, Y., Jiang, Y., Zhang, B., & Ma, N. (2021). Chronotype and depressive symptoms: A moderated mediation model of sleep quality and resilience in the 1st-year college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Wei, J., & Chen, C. (2022). The association between freshmen’s academic involution and college adjustment: The moderating effect of academic involution atmosphere. Tsinghua Journal of Education, 5, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Frequency (Percentage) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 203 (35.3%) |

| Female | 373 (64.7%) |

| Education level | |

| Undergraduate students | 465 (80.5%) |

| Postgraduate students | 111 (19.5%) |

| Types of universities | |

| Double First-Class universities | 316 (54.9%) |

| Other universities | 260 (45.1%) |

| Majors | |

| Humanities and social sciences | 358 (62.2%) |

| Natural sciences | 218 (37.8%) |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic delay of gratification | 2.968 | 0.668 | 1 | |||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.847 | 0.707 | −0.162 ** | 1 | ||

| Academic involution | 3.277 | 0.766 | 0.333 ** | 0.054 | 1 | |

| Academic resilience | 3.486 | 0.732 | 0.130 ** | −0.130 ** | 0.323 ** | 1 |

| Depressive Symptoms (Model 1) | Academic Involution (Model 2) | Depressive Symptoms (Model 3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | b | t | |

| Academic delay of gratification Academic involution | −0.167 | −3.779 *** | 0.398 | 8.721 *** | −0.209 | −4.467 *** |

| 0.106 | 2.619 ** | |||||

| R2 | 0.036 | 0.123 | 0.048 | |||

| F | 4.301 *** | 16.052 *** | 4.764 *** | |||

| Effect | Boot SE | Bootstrap 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | −0.209 | 0.047 | [−0.301, −0.117] |

| Indirect effect | 0.042 | 0.020 | [0.003, 0.082] |

| Total effect | −0.167 | 0.044 | [−0.254, −0.080] |

| Academic Involution | Depressive Symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | t | b | t | |

| Academic delay of gratification | 0.357 | 8.082 *** | −0.209 | −4.667 *** |

| Academic resilience | 0.286 | 7.164 *** | ||

| Academic delay of gratification × academic resilience | −0.106 | −2.018 * | ||

| Academic involution | 0.106 | 2.619 ** | ||

| R2 | 0.205 | 0.048 | ||

| F | 20.854 *** | 4.764 *** | ||

| Academic Resilience | Effect | Boot SE | Bootstrap 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderated mediation effect | eff1 (M − 1 SD) | 0.046 | 0.023 | [0.003, 0.094] |

| eff2 (M) | 0.038 | 0.018 | [0.002, 0.074] | |

| eff3 (M + 1 SD) | 0.030 | 0.016 | [0.002, 0.063] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, X.; Yang, W.; Cheng, T.; Gao, H. The Relationship Between Academic Delay of Gratification and Depressive Symptoms Among College Students: Exploring the Roles of Academic Involution and Academic Resilience. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111486

Ye X, Yang W, Cheng T, Gao H. The Relationship Between Academic Delay of Gratification and Depressive Symptoms Among College Students: Exploring the Roles of Academic Involution and Academic Resilience. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111486

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Xiaoli, Wei Yang, Tingting Cheng, and Haohao Gao. 2025. "The Relationship Between Academic Delay of Gratification and Depressive Symptoms Among College Students: Exploring the Roles of Academic Involution and Academic Resilience" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111486

APA StyleYe, X., Yang, W., Cheng, T., & Gao, H. (2025). The Relationship Between Academic Delay of Gratification and Depressive Symptoms Among College Students: Exploring the Roles of Academic Involution and Academic Resilience. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111486