Japanese Are Less Human-Centred than French: A New View on Spontaneous Perspective-Taking in Easterners

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure and Materials

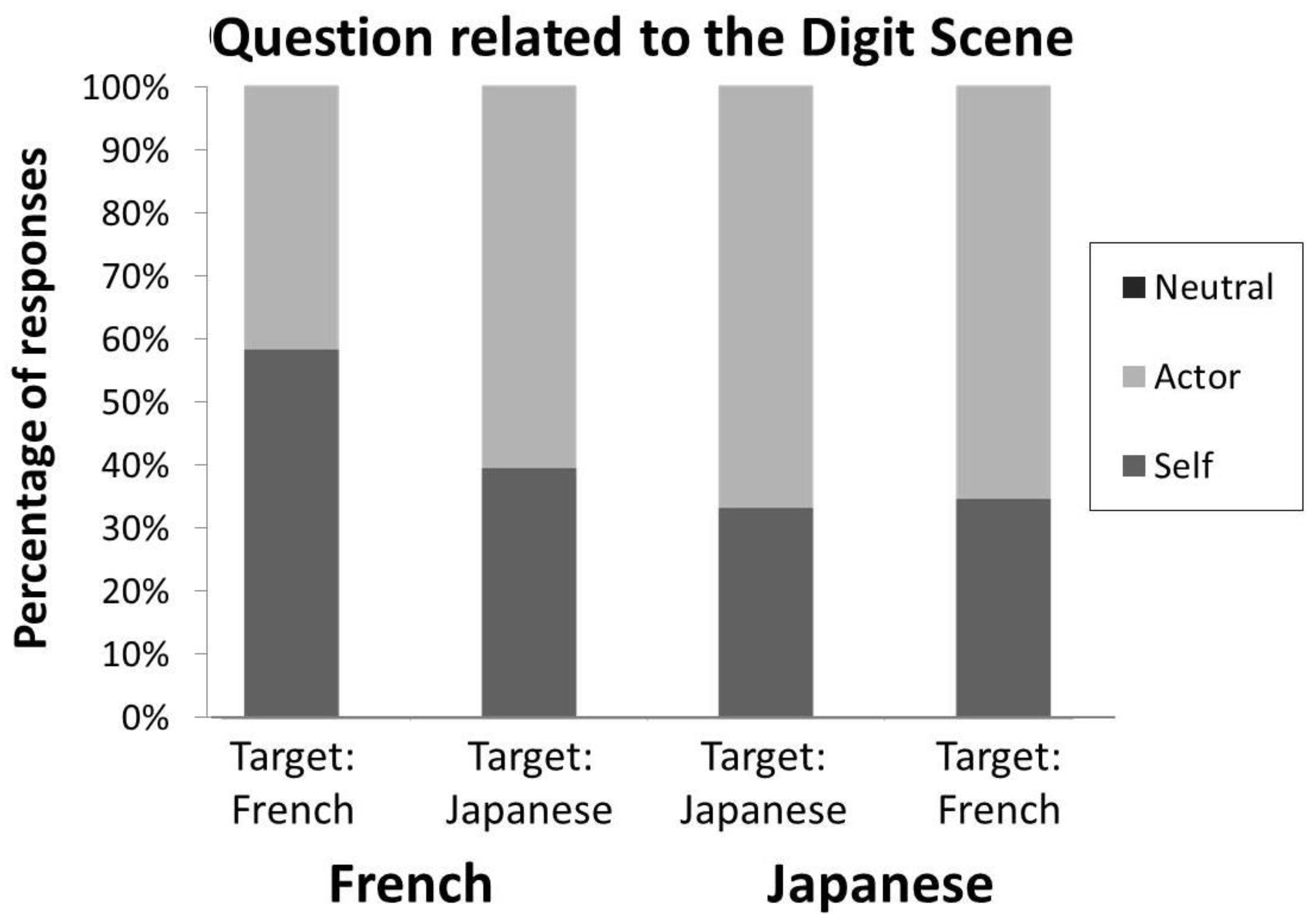

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashton-James, C. E., Maddux, W. W., Galinsky, A. D., & Chartrand, T. L. (2009). Who I am depends on how I feel: The role of affect in the expression of culture. Psychological Science, 20(3), 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, E. E., Jentzsch, I., Gomez, J. C., Chen, Y., Zhang, D., & Su, Y. (2018). Cross-cultural differences in adult Theory of Mind abilities: A comparison of native-English speakers and native-Chinese speakers on the self/other differentiation task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 71(12), 2665–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Contreras-Huerta, L. S., McFadyen, J., & Cunnington, R. (2015). Racial bias in neural response to others’ pain is reduced with other-race contact. Cortex, 70, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D., & Gunz, A. (2002). As seen by the other…: Perspectives on the self in the memories and emotional perceptions of Easterners and Westerners. Psychological Science, 13(1), 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, T. (1972). The anatomy of dependence. Kodansha. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, R., Wang, Y., Wei, C., Hou, X., Ju, K., Liang, Y., & Xi, J. (2023). Pursuing harmony and fulfilling responsibility: A qualitative study of the orientation to happiness (OTH) in Chinese culture. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epinat-Duclos, J., Foncelle, A., Quesque, F., Chabanat, E., Duguet, A., van Der Henst, J. B., & Rossetti, Y. (2021). Does nonviolent communication education improve empathy in French medical students? International Journal of Medical Education, 12, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N., Keysar, B., Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2004). Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J. H., Everett, B. A., Croft, K., & Flavell, E. R. (1981). Young children’s knowledge about visual perception: Further evidence for the Level 1–Level 2 distinction. Developmental Psychology, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J. H., Green, F. L., & Flavell, E. R. (1986). Development of knowledge about the appearance-reality distinction. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 51, i+iii+v+1–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlanetto, T., Cavallo, A., Manera, V., Tversky, B., & Becchio, C. (2013). Through your eyes: Incongruence of gaze and action increases spontaneous perspective taking. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilovich, T., Savitsky, K., & Medvec, V. H. (1998). The illusion of transparency: Biased assessments of others’ ability to read one’s emotional states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(2), 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, S. G., Ando, Y., Huang, C., Yee, A., & Lewis, R. S. (2010). Cultural differences in the visual processing of meaning: Detecting incongruities between background and foreground objects using the N400. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 5(2–3), 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeannerod, M., & Rossetti, Y. (1993). Visuomotor coordination as a dissociable visual function: Experimental and clinical evidence. Baillieres Clin Neurol, 2(2), 439–460. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, K., Cao, L., O’Shea, K. J., & Wang, H. (2014). A cross-culture, cross-gender comparison of perspective taking mechanisms. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1785), 20140388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihlstrom, J. F., Peterson, M. A., McConkey, K. M., Cranney, J., Gliskt, M. L., & Rose, P. M. (2018). Orientation and experience in the perception of form: A study of the Arizona Whale-Kangaroo. American Journal of Psychology, 131(2), 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. E., Jung, S. K., Song, H. J., & Warneken, F. (2025). US and Korean children prefer equality, but Korean children are more tolerant of ingroup-favoring allocations. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 262, 106375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, B. J., & Williams, E. N. (2019). Cultural differences in interpersonal emotion regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Derrington, E., Bénistant, J., Corgnet, B., Van der Henst, J. B., Tang, Z., Qu, C., & Dreher, J. C. (2023). Cross-cultural study of kinship premium and social discounting of generosity. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1087979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, A., Jha, A. P., Dunne, J. D., & Saron, C. D. (2015). Investigating the phenomenological matrix of mindfulness-related practices from a neurocognitive perspective. American Psychologist, 70(7), 632–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T., & Nisbett, R. E. (2001). Attending holistically versus analytically: Comparing the context sensitivity of Japanese and Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motokawa, T. (1989). Sushi science and hamburger science. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 32(4), 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, M., & Koyama, K. (2006). The development of false-belief understanding in Japanese children: Delay and difference? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30(4), 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbett, R. E., & Miyamoto, Y. (2005). The influence of culture: Holistic versus analytic perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(10), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesque, F., Apperly, I., Baillargeon, R., Baron-Cohen, S., Becchio, C., Bekkering, H., Bernstein, D., Bertoux, M., Bird, G., Bukowski, H., Burgmer, P., Carruthers, P., Catmur, C., Dziobek, I., Epley, N., Erle, T. M., Frith, C., Frith, U., Galang, C. M., … Brass, M. (2024). Defining key concepts for mental state attribution. Communications Psychology, 2(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesque, F., Chabanat, E., & Rossetti, Y. (2018). Taking the point of view of the blind: Spontaneous level-2 perspective-taking in irrelevant conditions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesque, F., Coutrot, A., Cox, S., de Souza, L. C., Baez, S., Cardona, J. F., Mulet-Perreault, H., Flanagan, E., Neely-Prado, A., Clarens, M. F., Cassimiro, L., Musa, G., Kemp, J., Botzung, A., Philippi, N., Cosseddu, M., Trujillo-Llano, C., Grisales-Cardenas, J. S., Fittipaldi, S., … Bertoux, M. (2022). Does culture shape our understanding of others’ thoughts and emotions? An investigation across 12 countries. Neuropsychology, 36(7), 664–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesque, F., Foncelle, A., Chabanat, É., Jacquin-Courtois, S., & Rossetti, Y. (2020). Take a seat and get into its shoes! when humans spontaneously represent visual scenes from the point of view of inanimate objects. Perception, 49(12), 1333–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, J. (2017). Probability theory and mathematical statistics. Available online: https://onlinecourses.science.psu.edu/stat414/node/268 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Samuel, S., Erle, T. M., Kirsch, L. P., Surtees, A., Apperly, I., Bukowski, H., Auvray, M., Catmur, C., Kessler, K., & Quesque, F. (2024). Three key questions to move towards a theoretical framework of visuospatial perspective taking. Cognition, 247, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitsky, K., Keysar, B., Epley, N., Carter, T. J., & Swanson, A. T. (2011). The closeness-communication bias: Increased egocentrism among friends versus strangers. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senzaki, S., Cowell, J. M., Shimizu, Y., & Calma-Birling, D. (2022). Emotion or evaluation: Cultural differences in the parental socialization of moral judgement. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16, 867308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama Lebra, T. (1976). Japanese patterns of behaviour. University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, A. R., Hanko, K., Galinsky, A. D., & Mussweiler, T. (2011). When focusing on differences leads to similar perspectives. Psychological Science, 22, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, B., & Hard, B. M. (2009). Embodied and disembodied cognition: Spatial perspective-taking. Cognition, 110, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S., Barr, D. J., Gann, T. M., & Keysar, B. (2013). How culture influences perspective taking: Differences in correction, not integration. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S., & Keysar, B. (2007). The effect of culture on perspective taking. Psychological Science, 18(7), 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X., Cusimano, C., & Malle, B. F. (2015). In search of triggering conditions for spontaneous visual perspective taking. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 37, 2811–2816. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quesque, F.; Imai, A.; Susami, K.; Niki, C.; Chabanat, E.; Foncelle, A.; Van der Henst, J.-B.; Kambara, A.; Rossetti, Y. Japanese Are Less Human-Centred than French: A New View on Spontaneous Perspective-Taking in Easterners. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111482

Quesque F, Imai A, Susami K, Niki C, Chabanat E, Foncelle A, Van der Henst J-B, Kambara A, Rossetti Y. Japanese Are Less Human-Centred than French: A New View on Spontaneous Perspective-Taking in Easterners. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111482

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuesque, François, Akira Imai, Kenji Susami, Chiharu Niki, Eric Chabanat, Alexandre Foncelle, Jean-Baptiste Van der Henst, Ayumi Kambara, and Yves Rossetti. 2025. "Japanese Are Less Human-Centred than French: A New View on Spontaneous Perspective-Taking in Easterners" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111482

APA StyleQuesque, F., Imai, A., Susami, K., Niki, C., Chabanat, E., Foncelle, A., Van der Henst, J.-B., Kambara, A., & Rossetti, Y. (2025). Japanese Are Less Human-Centred than French: A New View on Spontaneous Perspective-Taking in Easterners. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1482. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111482