1. Introduction

In second language education, the academic outcomes are shaped by not just the cognitive abilities of the learners, but also by their emotional and motivational experiences. The Control-Value Theory (CVT;

Pekrun, 2006) provides a thorough theoretical framework to understand the connections among emotions, motivation, and academic performance. As per CVT, achievement emotions come from the learners’ cognitive evaluations of control (like self-efficacy, perceived competence) and value (such as task importance, interest), which then influence learning engagement, strategy use, and final academic outcomes (

Pekrun & Perry, 2014). Recent advancements in educational psychology highlight that achievement emotions—be it positive or negative—play a crucial part in molding students’ engagement, persistence, and ultimate performance (

Jin & Zhang, 2021;

Liu & Song, 2021;

Liu et al., 2025c,

2025d). Within this field, English learning burnout (ELB) (for instance,

Liu & Zhong, 2022), academic buoyancy (AB) (

af Ursin et al., 2020;

Liu et al., 2025d), and foreign language enjoyment (FLE) (

Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014;

Jin & Zhang, 2021) have garnered specific scholarly attention.

Burnout in English learning is typically reflected in emotional exhaustion, disengagement, and a declining sense of accomplishment, which can undermine sustained effort and achievement (

Li et al., 2023). In contrast, academic buoyancy captures students’ everyday capacity to handle academic stressors and bounce back from setbacks, serving as a psychological shield against burnout (

Yun et al., 2018). Enjoyment in language learning, a positive emotional state, strengthens motivation and promotes deeper learning engagement (

Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2014).

Although prior research has investigated these variables, most studies have relied on variable-centered methods such as regression or structural equation modeling (

Dewaele & Dewaele, 2017;

Liu et al., 2025c;

Putwain & Wood, 2023). Such approaches often overlook the possibility that distinct combinations of these factors may jointly determine achievement. The fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) offers a useful alternative, as it identifies multiple causal pathways that can lead to the same outcome—a particularly relevant perspective in complicated educational settings (

Schneider & Wagemann, 2012).

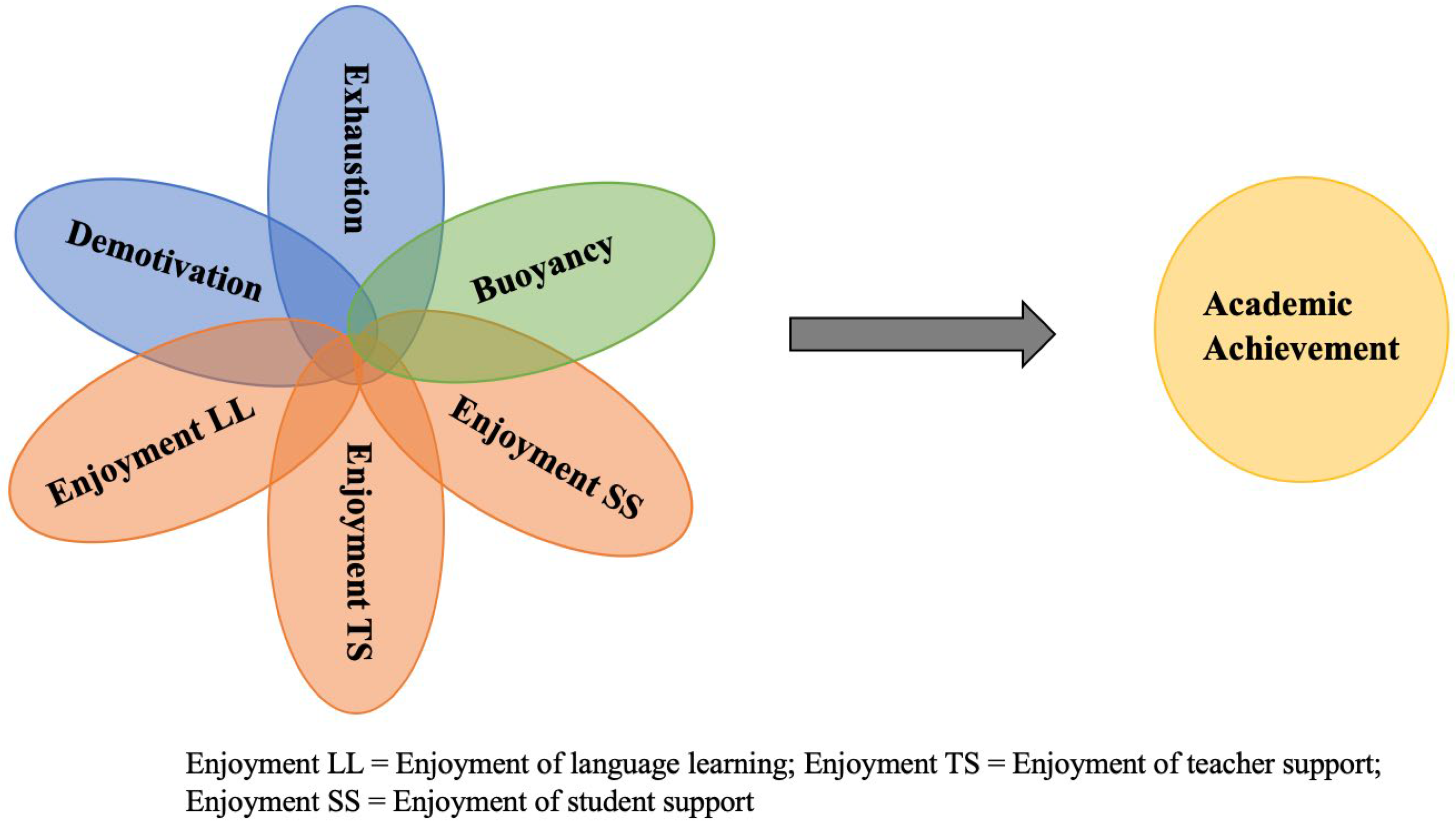

Within the Chinese senior high school system, where students face intense exam pressure, it is essential to understand how burnout, buoyancy, and enjoyment interact to shape learning outcomes. Addressing this gap, the present study applies fsQCA to examine how different configurations of these psychological variables predict English academic achievement, thereby contributing both to theory building and to the design of targeted pedagogical interventions.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Burnout, Buoyancy and Enjoyment

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the main research variables. The skewness and kurtosis showed that the data were normally distributed (

Kline, 2016). The mean score for academic achievement was 92.7, with a standard deviation of 23, ranging from 0 to 150. Among the affective variables, exhaustion had a mean of 2.30 (

SD = 0.90), while demotivation averaged 2.50 (

SD = 0.84), both measured on a 1–5 scale. In contrast, buoyancy showed a relatively higher mean of 3.32 (

SD = 0.91), suggesting moderate levels of learners’ capacity to cope with academic setbacks.

Regarding enjoyment, three dimensions were assessed: enjoyment of language learning (LL) had a mean of 3.39 (SD = 0.71), enjoyment of teacher support (TS) was highest at 4.40 (SD = 0.68), and enjoyment of student support (SS) had a mean of 3.78 (SD = 0.64). These results indicate that students experienced generally high levels of enjoyment, particularly from teacher support.

Table 3 illustrates the Pearson correlation coefficients among the variables. Academic achievement was significantly negatively correlated with exhaustion (r = −0.286,

p < 0.01) and demotivation (r = −0.264,

p < 0.01), indicating that higher levels of burnout and demotivation are associated with lower academic performance. In contrast, academic achievement was positively correlated with buoyancy (r = 0.201,

p < 0.01), enjoyment of language learning (r = 0.331,

p < 0.01), and to a lesser extent, with enjoyment of teacher support (r = 0.038, ns) and enjoyment of student support (r = 0.059, ns).

Notably, exhaustion and demotivation were highly positively correlated (r = 0.802, p < 0.01), suggesting they may co-occur as symptoms of language learning burnout. Both were significantly negatively correlated with buoyancy and all enjoyment dimensions. Conversely, buoyancy was strongly positively correlated with enjoyment of language learning (r = 0.700, p < 0.01), teacher support (r = 0.261, p < 0.01), and student support (r = 0.450, p < 0.01), highlighting its close connection with positive learning emotions.

4.2. Independent Predictive Effects of Burnout, Buoyancy and Enjoyment on Academic Achievement

The results of multiple regression analysis assessing the independent predictive effects of the variables on academic achievement are presented in

Table 4. Among the predictors, enjoyment in language learning (LL) emerged as a significant positive predictor of academic achievement (β = 0.327,

t = 5.379,

p < 0.001). In contrast, exhaustion showed a significant negative effect (β = −0.128,

t = −1.991,

p = 0.047), suggesting that higher levels of exhaustion hinder academic performance.

Other variables, including demotivation, buoyancy, enjoyment of teacher support, and enjoyment of student support, did not significantly predict academic achievement, although the direction of effects for enjoyment of teacher support and student support was negative, which may warrant further investigation. The non-significant coefficients suggest that external enjoyment sources may not directly translate into measurable performance gains once intrinsic enjoyment is accounted for.

4.3. Configurational Predictive Effects of Burnout, Buoyancy and Enjoyment on Academic Achievement

4.3.1. Necessity Analysis

After calibration, the necessity analysis was conducted to assess whether any individual condition is required for the outcome of high academic achievement. None of the conditions exceed the standard threshold of 0.90 for necessity (

Schneider & Wagemann, 2012), indicating that no single condition is necessary for high academic achievement. However, academic buoyancy and enjoyment of teacher support demonstrate relatively high consistency (>0.70), implying they may play significant roles as part of sufficient configurations (see

Table 5).

4.3.2. Sufficiency Analysis

The fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) revealed several distinct combinations of conditions sufficient for the presence (HAA) and absence (~HAA) of high academic achievement (see

Table 6). The overall solution for achieving HAA demonstrated acceptable reliability with a solution consistency of 0.805 and explained a substantial portion of the cases with a solution coverage of 0.610 (

Ragin, 2008;

Fiss, 2011). Five unique causal configurations (HAA1 to HAA5) were identified, each representing a different pathway to success.

One prominent pathway (HAA2), characterized by the presence of buoyancy and enjoyment of language learning, combined with the absence of exhaustion, demotivation, and enjoyment of teacher support, achieved a raw coverage of 0.505. This indicates this combination was present in over half of the cases exhibiting HAA (

Rihoux & Ragin, 2009). It also showed a notable unique coverage (0.127), highlighting its distinct contribution. Similarly, HAA1, which additionally required the presence of enjoyment of student support and absence of enjoyment of teacher support, showed robust consistency (0.879) and substantial unique coverage (0.042). This pathway underscores the critical role of positive affective states like buoyancy and enjoyment in learning activities, coupled with the avoidance of negative states like exhaustion and demotivation (

Martin & Marsh, 2008;

Pekrun et al., 2002). HAA3, HAA4 and HAA5, featuring the absence of both Enjoyment SS and Enjoyment TS alongside the presence of buoyancy and Enjoyment LL, all demonstrated high consistencies (0.890, 0.861, 0.880) but lower coverages (0.011, 0.013, 0.003). Learners represented by these configurations appear to be autonomous and self-regulated, relying primarily on internal motivation and emotional stability rather than on social support.

Conversely, the analysis identified a single, highly consequential configuration (NHAA1) sufficient for the absence of high academic achievement (~HAA). This pathway consistently (Consistency = 0.809) explained a majority of the underachievement cases (Raw Coverage = 0.564; Unique Coverage = 0.564). It is defined by the co-occurrence of exhaustion and demotivation, alongside the absence of buoyancy and enjoyment of language learning. The irrelevance of Enjoyment TS and Enjoyment SS in this configuration suggests that regardless of teacher’s aide or peer support, the core combination of high exhaustion, high demotivation, low buoyancy, and low enjoyment in learning itself is a potent barrier to academic success (

Salmela-Aro et al., 2009). The overall solution for ~HAA exhibited strong reliability (Solution Consistency = 0.809) and coverage (Solution Coverage = 0.564).

Overall, the fsQCA results underscore the complexity, asymmetry, and equifinality of affective and motivational influences on English learning achievement. Multiple distinct combinations of psychological and experiential conditions can lead to high achievement. The core elements across successful pathways consistently involve the presence of positive engagement (buoyancy, Enjoyment LL) and the absence of debilitating factors (exhaustion, demotivation). In stark contrast, underachievement is primarily driven by a singular, high-impact configuration dominated by negative states and the lack of core positive engagement, demonstrating asymmetry in the causal recipes for the outcome and its negation (

Schneider & Wagemann, 2012;

Woodside, 2013). These findings complement the regression results by demonstrating that linear effects alone cannot capture the interactive, non-linear patterns among burnout, buoyancy, and enjoyment. The configurational approach therefore provides richer explanatory power for understanding the psychological mechanisms underlying English academic performance among Chinese high-school learners.

6. Conclusions and Implication

This study enhances our comprehension of the way in which affective and motivational factors interact to impact English academic achievement within the context of senior high school students. Through the integration of regression analysis alongside fsQCA, the research has uncovered both the independent effects as well as the configurational effects pertaining to burnout, buoyancy, and enjoyment. The findings affirm that the intrinsic enjoyment derived from language learning stands out as the most potent individual predictor of achievement, whereas exhaustion tends to undermine performance. Furthermore, numerous different combinations of positive affective states together with personal resources—for instance, buoyancy, peer-related enjoyment, and intrinsic satisfaction—have been demonstrated to uphold high achievement, thereby exemplifying the principle of equifinality. Low achievement was mostly linked to a particular adverse situation marked by feelings of exhaustion, demotivation, as well as a lack of buoyancy and enjoyment. The difference in the predictors of success and failure highlights the significance of dealing with negative states, besides encouraging positive ones.

From a theoretical aspect, this research highlights the value of employing a configurational approach for comprehending academic achievement. Traditional regression models frequently presume symmetrical and linear connections, which pose a risk of concealing the multifaceted and interactive characteristics of psychological factors in the learning process. Through the application of fsQCA, this study illustrates that various combinations of burnout, buoyancy, and enjoyment can result in high achievement, thus reinforcing the principle of equifinality within educational psychology. This indicates that researchers ought to go beyond single-variable explanations and instead take into consideration the intricate, dynamic interplay of emotional and motivational states when developing theories about achievement emotions. Furthermore, the discovery that underachievement is mainly accounted for by a single harmful configuration emphasizes the principle of causal asymmetry, drawing attention to the fact that the paths to success and failure are not mere mirror images. These findings refine CVT by empirically confirming that emotional precursors to achievement operate asymmetrically—positive affective states (enjoyment, buoyancy) have a non-linear compensatory power, while negative states (burnout) exert dominant inhibitory effects. The integration with SDT further suggests that the satisfaction of autonomy and competence needs mediates these relationships. Hence, the study not only validates CVT in a language learning context but also contributes a refined, interaction-based model where affective configurations predict learning outcomes more accurately than single-variable effects.

From a pedagogical standpoint, the outcomes indicate that language educators as well as school administrators need to give priority to nurturing the intrinsic joy of learning activities, since it has been observed to predict achievement in a consistent manner across both independent and configurational analyses. Teachers can design autonomy-supportive activities (e.g., student-led projects), embed reflective self-regulation training, and introduce peer mentoring circles to simultaneously reduce exhaustion and enhance enjoyment. The classroom strategies that could be employed might involve crafting engaging and meaningful communicative tasks, promoting self-directed learning projects, and offering opportunities for students to experience mastery and competence. It is crucial to note that the enjoyment obtained solely from teacher or peer support was not enough to ensure higher performance. This suggests that social support ought to be utilized as a way to reinforce intrinsic engagement instead of being used as a replacement for it.

In summary, this study advances theory by showing how CVT can be extended through a configurational lens, capturing asymmetric and equifinal pathways to achievement. Methodologically, it demonstrates the added value of combining regression with fsQCA in educational psychology. Practically, the findings suggest that educators should prioritize nurturing students’ intrinsic enjoyment through engaging, meaningful learning activities, while simultaneously reducing exhaustion and demotivation. It is only when both sides of this emotional range are addressed that teachers and schools can foster sustainable accomplishment and psychological well-being in language learners. Specific strategies may include project-based learning, opportunities for autonomy, and stress-reduction interventions. Moreover, while teacher and peer support are important for emotional well-being, they should be leveraged to reinforce intrinsic engagement rather than substitute for it.

Despite its theoretical and methodological contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study employed convenience sampling from a single urban region in eastern China, which may limit the generalizability of results to other cultural or educational contexts. Future research should replicate these findings using multi-site or stratified samples to enhance representativeness. Second, the cross-sectional design restricts causal inference. Longitudinal or experience-sampling methods could better capture the temporal dynamics of emotion and achievement. Third, while fsQCA provides configurational insights, it does not establish causal directionality. Future studies could integrate longitudinal QCA or hybrid modeling (e.g., SEM–fsQCA) to triangulate causal mechanisms.