3. Results

Data analysis was conducted using R version 4.5.0 (

R Core Team, 2025). A two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using the

afex package (version 1.3-0;

Singmann et al., 2025) to examine the effects of pair type (cue-overlap vs. non-overlap) and list (List 1 vs. List 2) on associative recognition accuracy, with a significance level set at α = 0.05. Trials with reaction times (RTs) exceeding 5000 ms (2.36% of total trials) were excluded because the experimental design automatically advanced to the next trial after 5000 ms, indicating no response. Additionally, trials with recognition RTs < 200 ms or > 3

SD, and source judgment RTs < 100 ms or > 3

SD, were removed to ensure data quality.

To complement the frequentist analysis and provide a more nuanced assessment of the strength of evidence, Bayesian analyses were also conducted using the BayesFactor package in R (version 1.0.0;

Morey & Rouder, 2025). This approach allows quantifying the relative evidence for the alternative versus the null hypothesis through Bayes factors, offering a continuous measure of evidential strength rather than relying solely on threshold-based significance testing. The inclusion of Bayesian inference enhances the interpretability and robustness of the findings, aligning with best practices in contemporary psychological research (

Wagenmakers et al., 2018a,

2018b).

All data, analysis scripts, and materials are publicly available at the Open Science Framework:

https://osf.io/pfgca/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

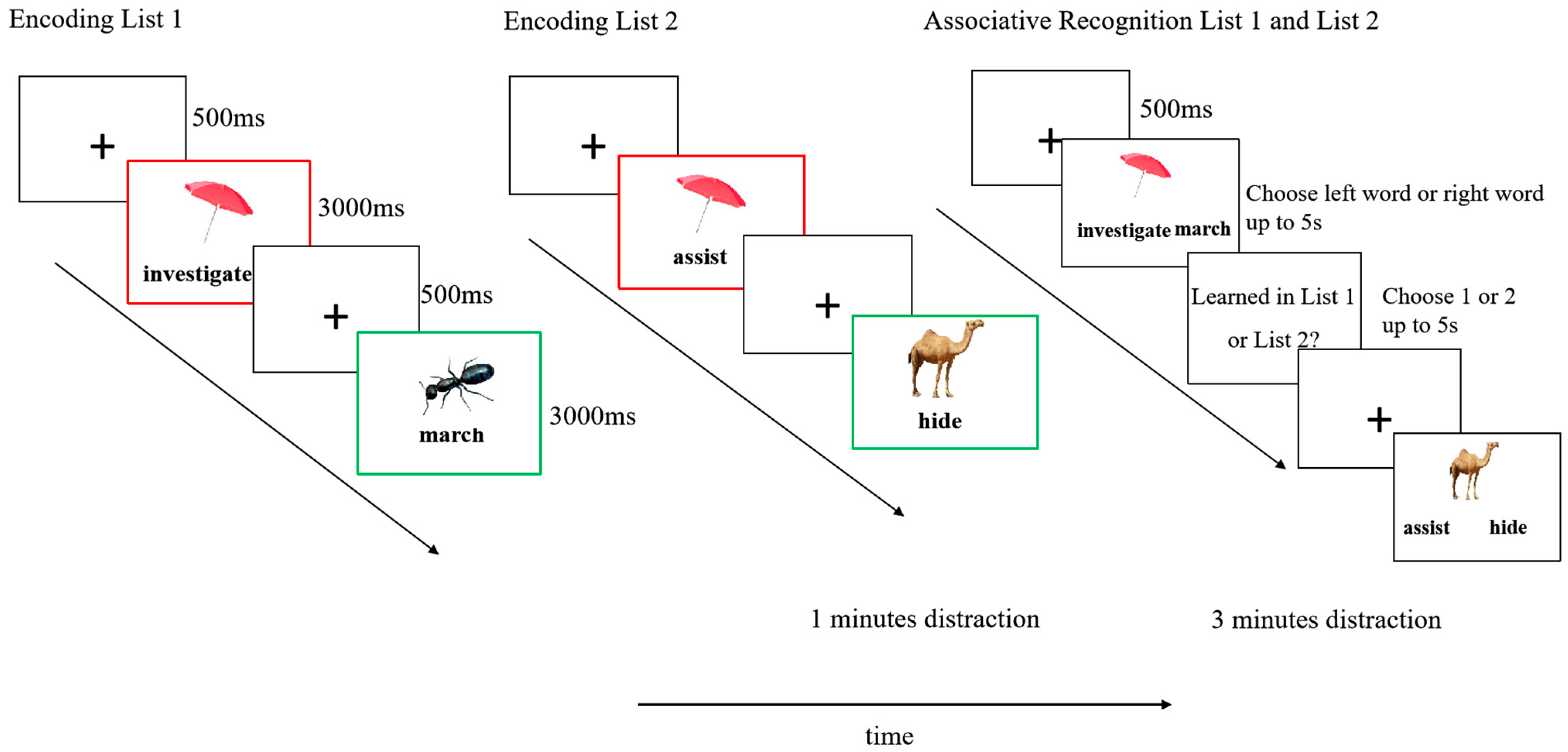

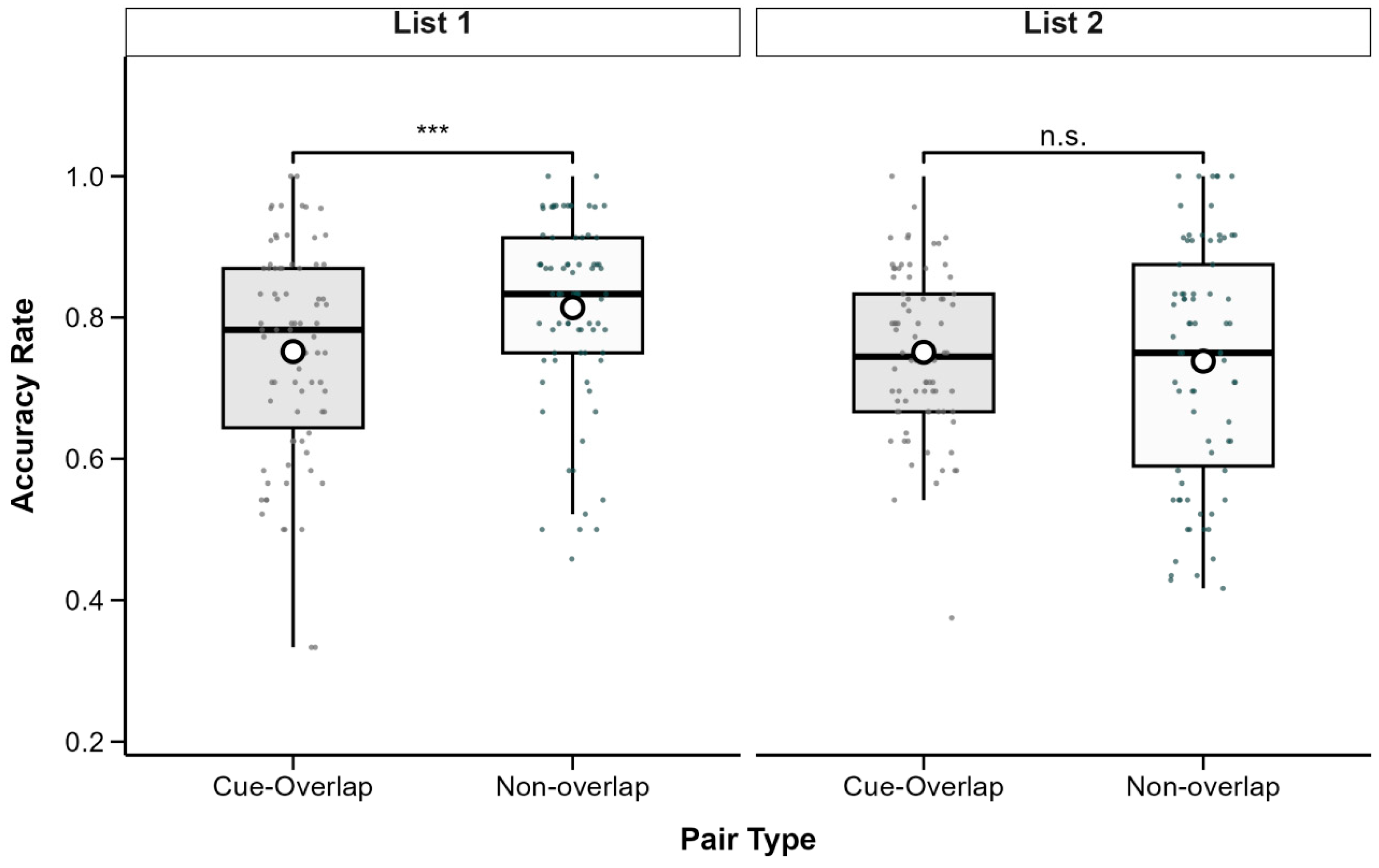

3.1. Associative Recognition Accuracy

Descriptive statistics for associative recognition accuracy are presented in

Table 1. A 2 (List: List 1 vs. List 2) × 2 (Pair Type: Cue-Overlap vs. Non-Overlap) repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of list,

F(1, 77) = 13.31,

p < 0.001, partial

η2 = 0.15, with higher accuracy observed in List 1 (

M = 0.78,

SD = 0.14) than in List 2 (

M = 0.75,

SD = 0.14). A significant main effect of pair type was also found,

F(1, 77) = 5.01,

p = 0.028, partial

η2 = 0.06, indicating higher accuracy for non-overlap pairs (

M = 0.78,

SD = 0.15) than for cue-overlap pairs(

M = 0.75,

SD = 0.13). The interaction between list and pair type was also significant,

F(1, 77) = 9.28,

p = 0.003, partial

η2 = 0.11 (see

Figure 2).

To explore this interaction, simple effects analyses were conducted using the

emmeans package (version 1.10.0;

Lenth et al., 2025). For List 1, accuracy was significantly higher for non-overlap pairs (

M = 0.81,

SD = 0.13) compared to cue-overlap pairs (

M = 0.75,

SD = 0.15),

t(77) = −4.45,

p < 0.001, Cohen’s

d = −0.50. In contrast, for List 2, there was no significant difference between cue-overlap (

M = 0.75,

SD = 0.11) and non-overlap pairs (

M = 0.74,

SD = 0.17),

t(77) = 0.68,

p = 0.50, Cohen’s

d = 0.08. All

p-values are two-tailed and Bonferroni-adjusted where applicable.

To quantify the strength of evidence for each effect, a Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted with list and pair type as within-subject factors (default Cauchy prior width r = 0.707).

The results provided strong evidence for a main effect of list (BF10 = 20.48), but only anecdotal evidence for a main effect of pair type (BF10 = 1.03).

The inclusion of the list and pair type interaction did not improve model fit (BF10 = 1.01), indicating that the evidence for an interaction was inconclusive.

Follow-up Bayesian paired-sample t-tests showed strong evidence for a difference between cue-overlap and non-overlap pairs in List 1 (BF10 = 643.0), but moderate evidence for no difference in List 2 (BF01 = 6.43).

These results suggest that while cue overlap influenced recognition accuracy in List 1, the effect did not generalize to List 2.

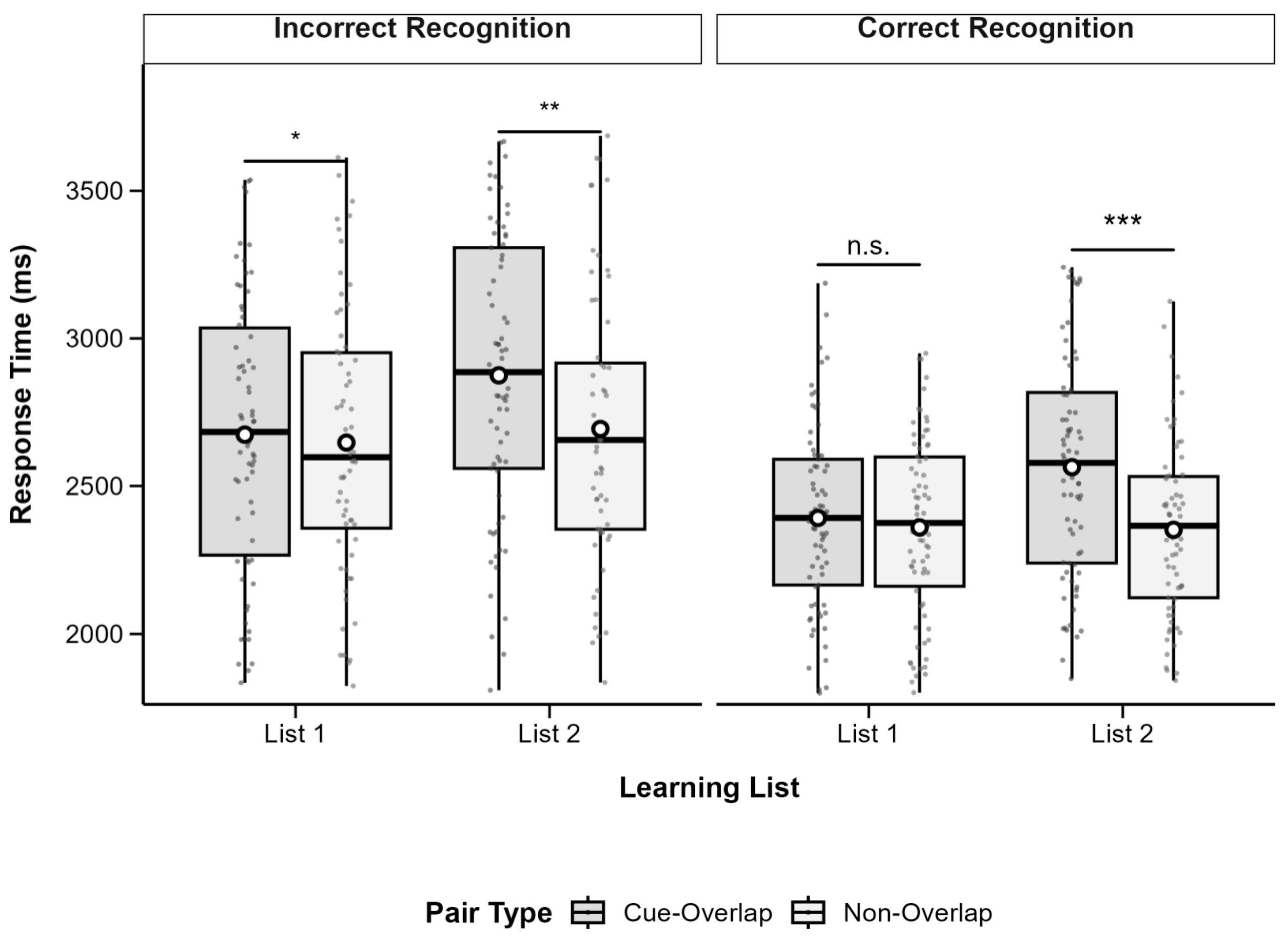

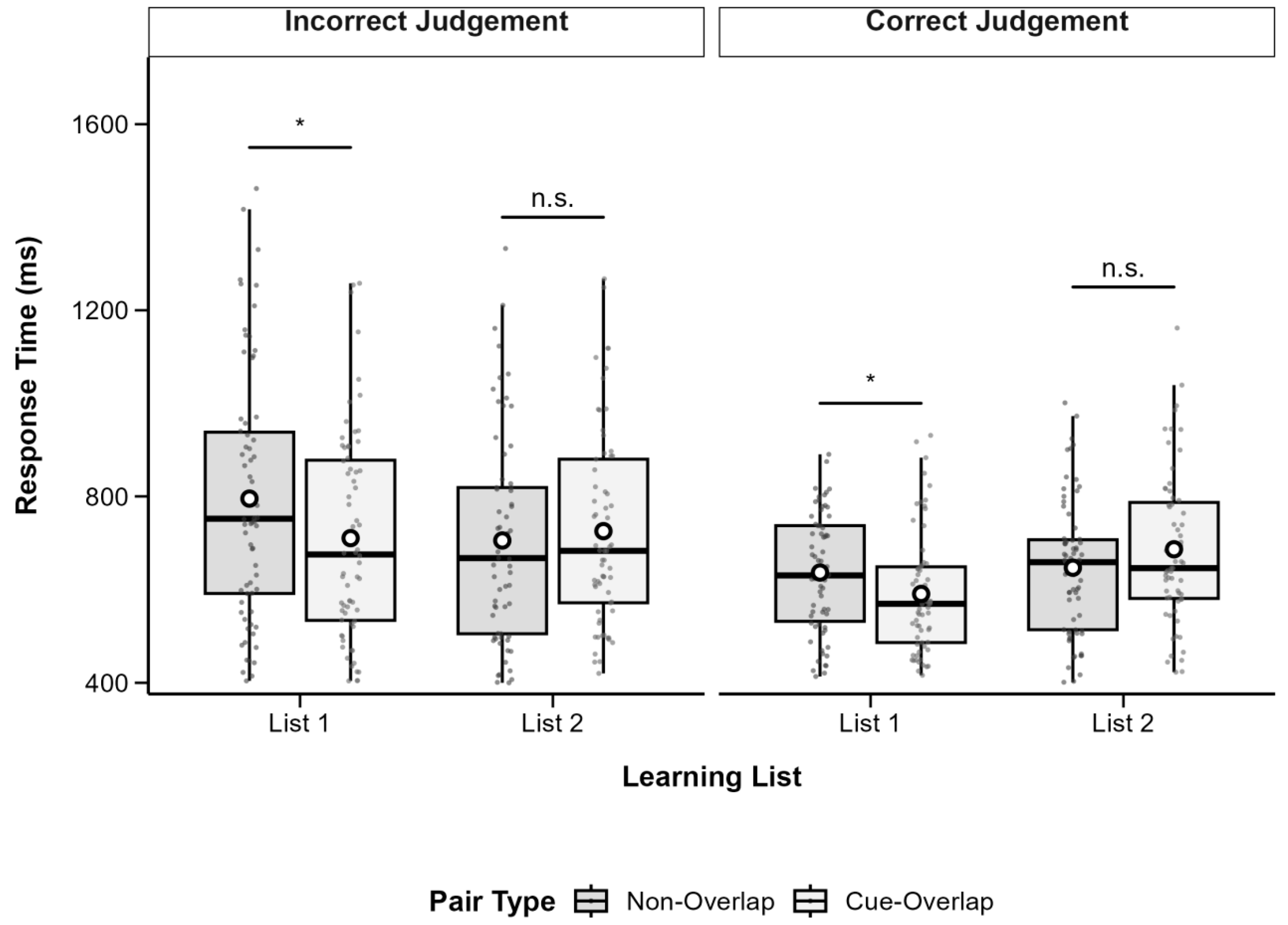

3.2. Associative Recognition Reaction Times

To complement the accuracy analysis, recognition reaction times (RTs) were analyzed to examine potential interference effects that may not be evident from accuracy alone.

Importantly, RTs from both correct and incorrect recognition trials were included in the analysis. Reporting RTs for all response outcomes is critical for several methodological and theoretical reasons. First, it rules out a potential speed–accuracy trade-off: if shorter RTs for correct trials merely reflected participants’ tendency to respond quickly at the expense of accuracy, error trials would be expected to show even faster responses. Instead, the data revealed the opposite pattern—errors were slower than correct responses—demonstrating that RT differences genuinely reflect variations in memory strength rather than strategic speed biases.

Second, analyzing RTs for incorrect trials provides insight into the nature of retrieval processes. Longer latencies on error trials indicate that incorrect responses stem not from impulsive guessing, but from more effortful and ultimately unsuccessful retrieval attempts. Third, these findings align with decision models of memory (e.g., diffusion or evidence accumulation models), which predict that decisions based on weak or ambiguous mnemonic evidence take longer to reach, regardless of accuracy. Finally, including both correct and incorrect responses ensures full data transparency and strengthens the interpretability of the results.

RTs were subjected to a 2 (List: List 1 vs. List 2) × 2 (Pair Type: Cue-Overlap vs. Non-Overlap) × 2 (Recognition Accuracy: Correct vs. Incorrect) repeated-measures ANOVA using the

afex package (version 1.3-0;

Singmann et al., 2025). Due to incomplete data, 7 participants were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 71 participants. Descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 1, and patterns are illustrated in

Figure 3.

The analysis revealed a significant main effect of list, F(1, 70) = 6.99, p = 0.010, partial η2 = 0.09, with shorter RTs in List 1 (M = 2491, SD = 353.7) than in List 2 (M = 2574, SD = 346.9). There was also a significant main effect of pair type, F(1, 70) = 15.12, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.18, with longer RTs for cue-overlap pairs (M = 2592, SD = 357.6) than non-overlap pairs (M = 2473, SD = 341.5). A highly significant main effect of recognition accuracy was found, F(1, 70) = 82.41, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.54, reflecting faster responses for correct (M = 2367, SD = 273.3) versus incorrect recognition (M = 2698, SD = 423.8).

A significant interaction emerged between list and pair type, F(1, 70) = 10.72, p = 0.002, partial η2 = 0.13. No significant interactions were observed between recognition accuracy and the other factors, all ps > 0.05. Follow-up comparisons indicated that for List 1, the RT difference between cue-overlap (M = 2513, SD = 383.7) and non-overlap pairs (M = 2469, SD = 368.2) was not significant, t(70) = 1.21, p = 0.231, Cohen’s d = 0.12. For List 2, RTs were significantly longer for cue-overlap (M = 2671, SD = 380.4) than for non-overlap pairs (M = 2477, SD = 369.7), t(70) = 4.86, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.51.

To further examine retrieval dynamics independent of recognition errors, a Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on reaction times (RTs) from correct recognition trials only, with list (List 1 vs. List 2) and pair type (Cue-Overlap vs. Non-Overlap) as within-subject factors (subject as a random factor; default Cauchy prior width r = 0.707).

Descriptive statistics indicated that mean RTs were slightly faster for non-overlap pairs (List 1: M = 2320 ms, SD = 347; List 2: M = 2273 ms, SD = 354) than for cue-overlap pairs (List 1: M = 2340 ms, SD = 363; List 2: M = 2513 ms, SD = 428).

At the model level, the Bayesian ANOVA provided anecdotal evidence for a main effect of list (BF10 = 2.04) and strong evidence for a main effect of pair type (BF10 = 3.59 × 104), suggesting that responses to cue-overlap pairs were generally slower than to non-overlap pairs. The incremental evidence for including the list and pair type interaction beyond the main-effects model was anecdotal (BF10 = 1.01), indicating that the interaction effect was not strongly supported.

Follow-up Bayesian paired-sample t-tests were conducted within each list. For List 1, the Bayes factor favored the null model (BF10 = 0.16, BF01 = 6.44), providing moderate evidence for no RT difference between cue-overlap and non-overlap pairs. For List 2, however, the Bayes factor provided decisive evidence for a difference (BF10 = 9.01 × 106), with non-overlap pairs eliciting faster responses than cue-overlap pairs.

Together, these findings indicate that, when recognition responses were correct, slower RTs for cue-overlap pairs primarily emerged in the second list, consistent with greater proactive interference during later encoding phases. The absence of a difference in List 1 suggests that retroactive interference was minimal when items were first encoded.

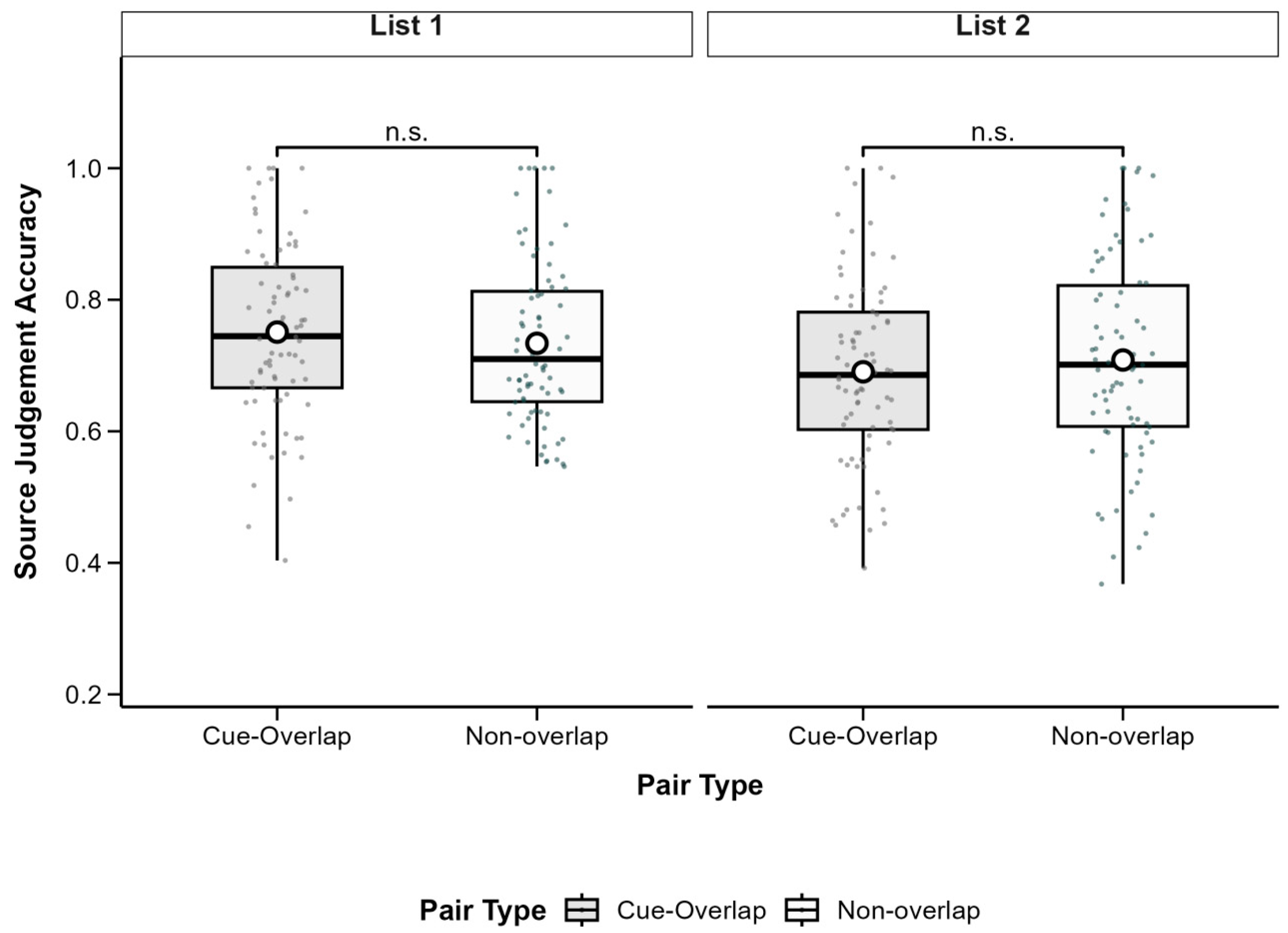

3.3. Source Judgement Accuracy

To examine source memory, we analyzed the proportion of correct source judgments for successfully recognized associations. A 2 (Pair Type: Cue-Overlap vs. Non-Overlap) × 2 (List: List 1 vs. List 2) repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of List,

F(1, 77) = 4.79,

p = 0.032, partial

η2 = 0.06, with higher source accuracy in List 1 (

M = 0.74,

SD = 0.14) than in List 2 (

M = 0.70,

SD = 0.15). The main effect of pair type was not significant,

F(1, 77) = 0.77,

p = 0.383, partial

η2 = 0.01, nor was the interaction,

F(1, 77) = 0.07,

p = 0.790, partial

η2 < 0.001. These findings suggest that cue overlap did not significantly affect source memory, although source accuracy was generally better for List 1. Descriptive statistics are shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 4.

To further assess source recognition performance beyond frequentist inference, a Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on accuracy data, with list (List 1 vs. List 2) and pair type (Cue-Overlap vs. Non-Overlap) as within-subject factors (subjects as a random factor; default Cauchy prior width r = 0.707).

The analysis provided moderate evidence for a main effect of list (BF10 = 4.06), indicating that overall source recognition accuracy was slightly higher for List 1 (M = 0.75, SD = 0.14) than for List 2 (M = 0.70, SD = 0.15). In contrast, there was moderate evidence for the null hypothesis regarding the main effect of pair type (BF10 = 0.16, BF01 = 6.25), suggesting that accuracy did not differ reliably between cue-overlap and non-overlap pairs. The inclusion of the list and pair type interaction yielded anecdotal evidence (BF10 = 1.01) in favor of an interaction, indicating that the data were essentially insensitive to this effect. To further examine potential list-specific effects, Bayesian paired-sample t-tests were performed within each list. For both List 1 (BF10 = 0.17, BF01 = 5.74) and List 2 (BF10 = 0.13, BF01 = 7.48), the Bayes factors provided moderate evidence supporting the null model, indicating that source recognition accuracy did not differ between cue-overlap and non-overlap pairs in either list.

Taken together, these Bayesian results suggest that while participants’ overall source memory was slightly better for items from the first list, pair-type overlap did not systematically influence source recognition accuracy, providing no compelling evidence for either proactive or retroactive interference in source attribution performance.

3.4. Source Judgement Reaction Times

In addition to accuracy analyses, response times (RTs) during the source judgment task were also examined to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the retrieval process. Reporting RTs alongside accuracy serves two purposes. First, it allows us to evaluate whether differences in performance are driven by memory processes rather than by a speed–accuracy trade-off. Second, it offers insights into the cognitive dynamics underlying correct and incorrect source judgments.

A 2 (List) × 2 (Pair Type) × 2 (Source Accuracy: Correct, Incorrect) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine mean response times during the source judgment task. Six participants were excluded due to missing data, yielding a final sample of 72 participants. Descriptive statistics are reported in

Table 2 and

Figure 5.

There was a significant main effect of source accuracy, F(1, 71) = 39.17, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.36, indicating faster RTs for correct judgments (M = 616.5, SD = 374.8) than incorrect judgments (M = 700.0, SD = 425.8). This pattern rules out a speed–accuracy trade-off: if errors reflected hasty or impulsive responding, error RTs would have been shorter. Instead, the opposite pattern was observed—errors were slower, suggesting that incorrect responses arose from more effortful and less fluent retrieval attempts. This RT asymmetry provides an important window into the cognitive mechanism of source memory. Correct judgments likely reflect the retrieval of strong and distinctive contextual representations, supporting fluent and confident decisions. In contrast, incorrect judgments are presumably based on weak, ambiguous, or competing memory traces, resulting in prolonged decision times as participants search for or evaluate insufficient memory evidence. This interpretation aligns with evidence-accumulation models of decision making, which propose that responses based on degraded evidence take longer to reach a decision threshold, even when the final decision is incorrect.

The main effect of pair type was marginal, F(1, 71) = 3.36, p = 0.071, partial η2 = 0.05, suggesting slightly faster RTs for cue-overlap (M = 645.5, SD = 392.8) compared to non-overlap pairs (M = 671.0, SD = 407.8). The main effect of the list was not significant, F(1, 71) = 0.02, p = 0.880, partial η2 < 0.01.

Significant two-way interactions were found between list and pair type, F(1, 71) = 8.96, p = 0.004, partial η2 = 0.11, and between list and source accuracy, F(1, 71) = 8.09, p = 0.006, partial η2 = 0.10. A significant three-way interaction was also observed among list, pair type, and source accuracy, F(1, 71) = 4.85, p = 0.031, partial η2 = 0.06. To follow up on the three-way interaction, we first examined the interaction between list and pair type separately for correct and incorrect source judgments. When source judgments were incorrect, the interaction between list and pair type was significant, F(1, 71) = 8.68, p = 0.005. Simple effects analyses revealed that in List 1, RTs were significantly slower for non-overlap pairs (M = 764, SD = 443.0) than for cue-overlap pairs (M = 674, SD = 406.0), t(71) = −2.46, p = 0.017, Cohen’s d = −0.29. In contrast, in List 2, the difference between cue-overlap (M = 710, SD = 427.0) and non-overlap pairs (M = 652, SD = 427.0) was not significant, t(71) = 1.65, p = 0.104. For correct source judgments, the interaction between list and pair type was not significant, F(1, 71) = 1.02, p = 0.316. However, a significant simple effect of pair type was observed in List 1, with cue-overlap pairs eliciting faster responses (M = 572, SD = 344) than non-overlap pairs (M = 619, SD = 381), t(71) = −2.55, p = 0.013, Cohen’s d = −0.30. In List 2, the difference was non-significant, t(71) = −1.30, p = 0.198, with mean RTs of 626 (SD = 394.0) for cue-overlap and 649 (SD = 380) for non-overlap pairs.

To further verify the results of the frequentist repeated-measures ANOVA, a Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on the mean source-recognition reaction time (RT) for correctly recognized trials, with List (List 1 vs. List 2) and Pair Type (Cue-overlap vs. Non-overlap) as within-subject factors. Default Cauchy priors were used (r = 0.707).

Across participants, mean RTs were 565 ms (SD = 170) for cue-overlap and 611 ms (SD = 184) for non-overlap pairs in List 1, and 619 ms (SD = 203) and 639 ms (SD = 184, respectively, in List 2. Overall, recognition decisions were faster for cue-overlap than for non-overlap pairs, particularly in List 1.

The Bayesian ANOVA revealed strong evidence for a main effect of List (BF10 = 41.30), indicating that mean RTs differed reliably between the two lists. There was moderate evidence for a main effect of Pair Type (BF10 = 4.55), suggesting that RTs were overall shorter for cue-overlap than for non-overlap pairs. The inclusion of the List and Pair Type interaction only provided anecdotal evidence (BF10 = 1.01) beyond the main-effects model, implying that the evidence for an interaction effect is weak and inconclusive.

To further clarify the direction and magnitude of the effects within each list, Bayesian paired-samples t tests compared the two pair types separately for each list.

In List 1, there was moderate evidence for a difference between cue-overlap and non-overlap pairs (BF10 = 3.25), with faster responses for cue-overlap pairs. In List 2, however, the Bayes factor (BF10 = 0.25) provided moderate evidence for the null hypothesis, indicating no meaningful difference between the two pair types in that list.

These Bayesian findings were largely consistent with the frequentist ANOVA in revealing reliable main effects of both List and Pair Type. However, unlike the frequentist analysis, which detected a statistically significant List and Type interaction, the Bayesian results provided only anecdotal evidence for this interaction (BF10 = 1.01), indicating that the strength of evidence for the interaction is weak.

Importantly, the pattern of reaction times revealed that source judgments for cue-overlap pairs were faster than those for non-overlap pairs, particularly in the first list. This result deviates from the initial prediction that cue overlap would impair source discrimination due to increased mnemonic similarity or integration. Instead, the shorter RTs for cue-overlap pairs suggest that the retrieval process for these associations was more fluent and efficient. This pattern implies that the overlapping cue context may have facilitated the differentiation of memory traces rather than producing interference, reflecting a stronger and more distinctive encoding of the source information associated with shared cues.

4. Discussion

4.1. Differential Manifestations of Retroactive and Proactive Interference

The present study revealed distinct patterns for retroactive (RI) and proactive interference (PI) in associative recognition and source memory tasks. In List 1, cue-overlap pairs (A-B) showed reduced recognition accuracy relative to non-overlapping pairs (E-F), whereas their reaction times did not differ significantly. This selective accuracy impairment without a corresponding latency cost is consistent with retroactive interference, suggesting that subsequent A-C learning disrupted access to previously encoded A-B associations. In contrast, in List 2, recognition accuracy did not differ between cue-overlap (A-C) and non-overlap (G-H) pairs, yet reaction times were markedly slower for overlapping associations. This latency cost in the absence of accuracy differences indicates proactive interference, reflecting increased retrieval difficulty caused by residual activation of earlier A-B traces.

Together, these findings demonstrate that RI and PI, though both arising from overlapping associative structures, manifest differently: RI primarily weakens memory strength or accessibility, while PI primarily slows retrieval fluency through competition between coactivated traces. These behavioral dissociations support the view that interference reflects multiple underlying mechanisms, which may dominate at different learning stages or depend on the representational organization of memory traces.

4.2. Mechanistic Differences Between RI and PI: Encoding and Retrieval Contributions

Retroactive interference (RI) appears to arise mainly from (re)encoding-based reorganization: when List 2 cue-overlap pairs (A-C) are encoded, partial reactivation of List 1 cue-overlap pairs (A-B) traces can trigger representational integration or differentiation within the hippocampal–mPFC network (

Chanales et al., 2019;

Kuhl et al., 2010;

Ritvo et al., 2019). In cases where reactivation is strong, pattern completion promotes integration between A-B and A-C, producing blended representations that reduce the distinctiveness of the original association and impair later recognition—a hallmark of RI.

In contrast, proactive interference (PI) likely reflects retrieval-based competition: when participants attempt to retrieve A-C associations, residual activation of previously learned A-B pairs coactivates competing responses, delaying selection of the correct target and thereby prolonging reaction times (

Anderson, 2003;

G.-J. Mensink & Raaijmakers, 1988). The presence of a strong PI-related latency cost, even under non-competitive test conditions, suggests that the competition originates from cue-driven coactivation of overlapping representations, rather than from explicit decision conflict at test.

Thus, RI and PI differ not only in behavioral manifestation but also in their underlying mechanisms—RI reflects representational interference formed during encoding, whereas PI reflects retrieval interference among coactivated traces. These complementary processes jointly contribute to the overall pattern of associative interference observed in episodic memory.

4.3. Encoding–Retrieval Interaction in Associative Interference

The combined results from associative recognition and source memory tasks support an integrated framework in which encoding-based reactivation and retrieval-based competition interact dynamically to shape memory performance.

At encoding, overlapping associations trigger reactivation of prior traces, leading to either integration (shared, overlapping representations) or differentiation (distinct, segregated representations). These representational outcomes determine the degree of overlap that later governs retrieval competition. When integration predominates, cue overlap amplifies associative similarity, increasing retrieval competition and thus producing RI or PI effects. Conversely, when differentiation occurs, overlapping traces become more distinct, reducing interference and potentially facilitating faster, more accurate retrieval.

The current finding that source judgments were faster for cue-overlap pairs, particularly in List 1, provides behavioral evidence consistent with differentiation. Rather than producing confusion between contexts, shared cues appeared to enhance the distinctiveness of their associated sources, enabling more fluent retrieval of contextual information. This pattern suggests that, under certain encoding conditions, reactivation may promote representational sharpening rather than blending, reducing cross-list interference while strengthening contextual discrimination.

Together, these results demonstrate that encoding-based and retrieval-based mechanisms are not independent but mutually constraining. Encoding determines the structural similarity among memory traces through reactivation-driven reorganization, whereas retrieval reveals the functional consequences of that structure through competitive access dynamics. The interaction between these processes explains why RI and PI can vary asymmetrically across learning lists and why interference effects persist even in non-competitive testing contexts.

This study extends traditional retrieval-based accounts of interference (e.g.,

Anderson, 2003;

Raaijmakers & Shiffrin, 1981) by showing that interference can arise even when overt retrieval competition is minimized, underscoring the importance of encoding dynamics in shaping later memory accessibility. By integrating the principles of pattern reactivation and reorganization from recent neurocognitive models (

Ritvo et al., 2019;

Schlichting & Preston, 2015) with the classic retrieval competition framework, the current findings highlight that interference emerges from the interaction between how memories are structured at encoding and how they are accessed at retrieval.

In this view, encoding and retrieval form a continuous, interactive loop: encoding determines representational similarity, which governs retrieval competition, while retrieval outcomes feed back to influence future encoding through selective reactivation. Understanding interference, therefore, requires a dynamic, cross-stage perspective—one that integrates both representational and functional dimensions of memory. This framework not only reconciles prior discrepancies between RI and PI findings but also provides a process-level explanation for how overlapping experiences can produce either competition or facilitation, depending on the nature of encoding reactivation.

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

While the present study offers important insights into the asymmetric mechanisms of retroactive and proactive interference and the central role of encoding processes, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the use of weakly associated word–picture pairs and brief encoding durations may have constrained the engagement of recollection-based retrieval, potentially amplifying familiarity-driven recognition effects. Given that associative recognition often relies on recollection, future studies should systematically manipulate associative strength and encoding duration to disentangle the relative contributions of familiarity and recollection under varying memory demands (

Yonelinas, 2002;

Wixted, 2007).

Second, although the two-alternative forced-choice (2AFC) paradigm employed here effectively minimized retrieval competition, it may not fully capture the complexity of naturalistic memory interference, where multiple associative traces may simultaneously compete during recall. Incorporating complementary paradigms—such as free recall, cued recall, or retrieval-induced forgetting tasks—could provide a richer characterization of how encoding- and retrieval-based mechanisms jointly shape interference effects (

Anderson, 2003;

Hulbert & Norman, 2015).

Third, while we highlight the pivotal role of encoding dynamics (e.g., pattern separation and differentiation) in shaping interference, this study did not directly measure neural correlates of encoding processes, such as hippocampal activity patterns or neural similarity metrics. Future research could integrate neuroimaging or computational modeling approaches (e.g., CLS models,

Norman & O’Reilly, 2003) to test how encoding operations like pattern suppression or representational repulsion (

Favila et al., 2020) mediate the trade-off between reduced interference and potential costs to recollection.

Finally, individual differences in encoding strategies, cognitive control, and working memory capacity may systematically modulate the degree of interference observed. Our findings suggest that adaptive encoding processes (e.g., differentiation) can either mitigate or exacerbate interference depending on individual strategy use. Future studies could examine these factors by including executive function measures or strategy assessments as covariates or moderators, which would deepen our understanding of variability in interference effects across individuals.

In summary, while this study advances the theoretical account of memory interference by emphasizing encoding as a critical locus of both retroactive and proactive effects, future research should adopt multi-method and multi-level approaches—combining behavioral paradigms, neural measures, and computational modeling—to further clarify the interplay between encoding and retrieval processes in shaping associative memory.