The Evolutionary Psychology of Breaking Informal Versus Formal Contracts: Effects of Group Size and Area of Upbringing

Abstract

1. The Evolutionary Psychology of Breaking Informal Versus Formal Contracts: Effects of Group Size and Area of Upbringing

1.1. The Evolutionary Psychology of Social Contracts

1.2. Large- Versus Small-Scale Societies in Evolutionary Perspective

1.3. Dispositional and Demographic Factors Related to the Psychology of Contracts

1.4. Primary Hypotheses

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. ANOVA Testing for Effects of Type of Agreement and Community Size

3.2. Correlation and Multiple Regression Testing: Demographic and Trait Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. The Effects of Social Scale and of Nature of Contract on Probability of Breaking the Contract

4.2. Dispositional and Demographic Correlates of Breaking Deals

4.3. Limitations of Current Research and Implications for Future Research

4.4. Implications for Living

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, white women. Health Psychology, 19, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, R. (1984). The evolution of cooperation. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, L., & Jonason, P. K. (2022). Contract cheating and the dark triad traits. In S. E. Eaton, & P. Barclay (Eds.), Reputation. The handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 1–19). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, M., & Tajfel, H. (1973). Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 3, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, D. J. Y., Campbell, G., Jackson, M., & Smith, R. H. (2010). Exploring the consequences of humiliating a moral transgressor. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 32(2), 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmides, L. (1989). The logic of social exchange: Has natural selection shaped how humans reason? Studies with the Wason selection task. Cognition, 31(3), 187–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1992). Cognitive adaptations for social exchange. In J. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Danielson, S. W., Stewart, E., & Vonasch, A. (2023). The morality map: Does living in a smaller community cause greater concern for moral reputation? Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 4, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D., Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2015). Social class, power, and selfishness: When and why upper and lower class individuals behave unethically. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunbar, R. I. M. (1992). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 22, 469–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, A. J., Brumbach, B. H., Jones, D. N., Sefcek, J. A., Vasquez, G., & Jacobs, W. J. (2008). Ecological constraints on mating tactics. In G. Geher, & G. Miller (Eds.), Mating intelligence: Sex, relationships, and the mind’s reproductive system (pp. 337–365). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Figueredo, A. J., Vásquez, G., Brumbach, B. H., & Schneider, S. M. R. (2007). The K-factor: Individual differences in life history strategy. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, A. J., Wolf, P. S. A., Olderbak, S. G., Gladden, P. R., Fernandes, H. B. F., Wenner, C., Hill, D., Andrzejczak, D. J., Sisco, M. M., Jacobs, W. J., Hohman, Z. J., Sefcek, J. A., Kruger, D., Howrigan, D. P., MacDonald, K., & Rushton, J. P. (2014). The psychometric assessment of human life history strategy: A meta-analytic construct validation. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 8, 148–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitness, A. (2001). Betrayal, rejection, revenge, and forgiveness: An interpersonal script approach. In M. Leary (Ed.), Interpersonal rejection (pp. 73–103). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geher, G. (2014). Evolutionary psychology 101. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Geher, G., Carmen, R., Guitar, A., Gangemi, B., Sancak Aydin, G., & Shimkus, A. (2015). The evolutionary psychology of small-scale versus large-scale politics: Ancestral conditions did not include large-scale politics. European Journal of Social Psychology, 46, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geher, G., Di Santo, J., & Planke, J. (2019a). Social reputation. In T. Shackelford (Ed.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary science. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Geher, G., Fritche, M., Goodwine, A., Lombard, J., Longo, K., & Montana, D. (2023). An Introduction to positive evolutionary psychology (D. Bjorklund, Ed.). Cambridge Elements in Applied Evolutionary Science. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geher, G., Rolon, V., Holler, R., Baroni, A., Gleason, M., Nitza, E., Sullivan, G., Thomson, G., & Di Santo, J. M. (2019b). You’re dead to me! The evolutionary psychology of social estrangements and social transgressions. Current Psychology, 40, 4516–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geher, G., & Wedberg, N. (2022). Positive evolutionary psychology: Darwin’s guide to living a richer life. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giphart, R., & Van Vugt, M. (2018). Mismatch. Robinson. [Google Scholar]

- Grable, J. E. (2000). Financial risk tolerance and additional factors that affect risk taking in everyday money matters. Journal of Business Psychology, 14, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruskin, K., Griffin, M., Bansal, S., Dickinson-Frevola, S., Dykeman, A., Groce-Volinski, D., Henriquez, K., Kardas, M., McCarthy, A., Shetty, A., Staccio, B., Geher, G., & Eisenberg, E. (2025). Stakeholders’ roles in evolutionizing education: An evolutionary-based toolkit surrounding elementary education. Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2013). Time varying risk aversion. Journal of Financial Economics, 128, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, M. S., & Villa, M. (2006). Big Brother in rural societies: Youths’ discourses on gossip. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift. Norwegian Journal of Geography, 60, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, L. P., Noordewier, M. K., Seck, L., & van Dijk, W. W. (2024). Financial scarcity and financial avoidance: An eye-tracking and behavioral experiment. Psychological Research, 88, 2211–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P. K., Kaufman, S. B., Webster, G. D., & Geher, G. (2013). What lies beneath the dark triad dirty dozen: Varied relations with the big five. Individual Differences Research, 11, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychological Assessment, 22, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappesser, J., & de C Williams, A. C. (2008). Pain judgements of patients’ relatives: Examining the use of social contract theory as theoretical framework. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(4), 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J., Smith, A., Atherton, I., & McLaughlin, D. (2015). “Everybody knows everybody else’s business”—Privacy in rural communities. Journal of Cancer Education, 31, 811–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenfors, P., Wartel, A., & Lind, J. (2021). ‘Dunbar’s number’ deconstructed. Biology Letters, 17(5), 20210158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, J. H., Cordain, L., Jones, P. G., & Abuissa, H. (2006). Coronary artery disease prognosis and C-reactive protein levels improve in proportion to percent lowering of low-density lipoprotein. The American Journal of Cardiology, 98, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piff, P. K., Stancato, D. M., Côté, S., Mendoza-Denton, R., & Keltner, D. (2012). Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109, 4086–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raihani, N. J., & Power, E. A. (2021). No good deed goes unpunished: The social costs of prosocial behaviour. Evolutionary Human Sciences, 3, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruel, M. K., De’Jesús, A. R., Cristo, M., Nolan, K., Stewart-Hill, S. A., DeBonis, A. M., Goldstein, A., Frederick, M., Geher, G., Alijaj, N., Elyukin, N., Huppert, S., Kruchowy, D., Maurer, E., Santos, A., Spackman, B. C., Villegas, A., Widrick, K., Wojszynski, C., & Zezula, V. (2022). Why should I help you? A study of betrayal and helping. Current Psychology, 42, 17825–17834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spikins, P. (2015). The geography of trust and betrayal: Moral disputes and late Pleistocene dispersal. Open Quaternary, 1(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlerick, M. (2020). The evolution of social contracts. Journal of Social Ontology, 5, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissberger, G. H., Han, S., Yu, L., Barnes, L. L., Lamar, M., Bennett, D. A., & Boyle, P. A. (2022). Subjective socioeconomic status is associated with risk aversion in a community-based cohort of older adults without dementia. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 963418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. S. (2019). This view of life: Completing the Darwinian revolution. Pantheon. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Group. (2025). Open data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Zimbardo, P. (2007). The lucifer effect: Understanding how good people turn evil. Random House. [Google Scholar]

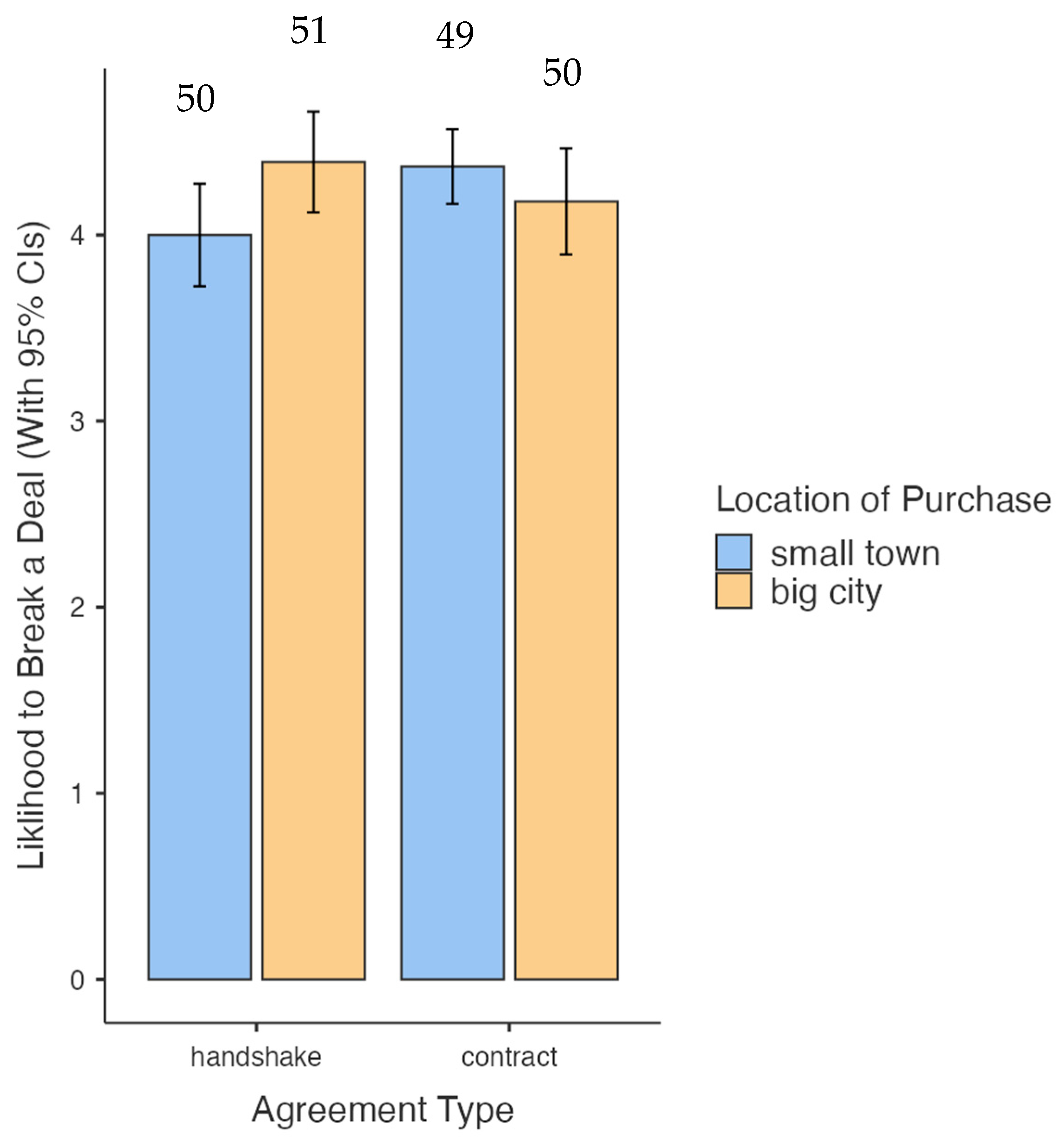

| Agreement Type | Location of Purchase | Likelihood of Breaking Deal (1–5) Mean | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handshake | Small town | 4 | 0.97 | 50 |

| Big city | 4.39 | 0.96 | 51 | |

| Total | 4.19 | 0.98 | 101 | |

| Contract | Small town | 4.37 | 0.7 | 49 |

| Big city | 4.18 | 1 | 50 | |

| Total | 4.27 | 0.87 | 99 | |

| Total | Small town | 4.18 | 0.86 | 99 |

| Big city | 4.29 | 0.98 | 101 | |

| Total | 4.24 | 0.92 | 200 |

| Continuous Predictor Variables | N | Mean (SD) |

| Age | 187 | 19.60 (2.37) |

| Ladder (Childh) 1 | 183 | 4.98 (1.74) |

| Dirty Dozen (total): 2 | ||

| Machiavellianism | 199 | 11.03 (5.04) |

| Psychopathy | 197 | 7.40 (3.89) |

| Narcissism | 194 | 13.26 (5.27) |

| PL_Urban 3 | 188 | 2.80 (1.44) |

| PL_Suburban | 189 | 3.65 (1.38) |

| PL_Rural | 182 | 2.13 (1.34) |

| Categorical Predictor Variables | N | % |

| Gender Iden. | 199 | |

| Female | 132 | 66.33 |

| Male | 48 | 24.12 |

| Non-binary | 13 | 6.53 |

| PNS * | 4 | 2.01 |

| Age | PLU Urban | PLU Sub. | PLU Rural | SES Child-Hood | Machiavellianism | Psychopathy | Narcissism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Break Deal | 0.011 | 0.246 ** | −0.092 | 0.039 | −0.161 * | 0.088 | 0.026 | 0.024 |

| N | 187 | 188 | 189 | 182 | 183 | 199 | 197 | 194 |

| Key Predictor Variables | b | B | sr2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban Area of Upbringing | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.07 ** |

| Suburban Area of Upbringing | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.02 |

| Rural Area of Upbringing | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.03 * |

| SES-Childhood | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geher, G.; Eisenberg, E.; DeMaio, M.; Casa, O.; Caserta, A.J.; Cochran, K.; Cohen, L.; Dewan, A.; Dickinson-Frevola, S.; Fenigstein, L.; et al. The Evolutionary Psychology of Breaking Informal Versus Formal Contracts: Effects of Group Size and Area of Upbringing. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111458

Geher G, Eisenberg E, DeMaio M, Casa O, Caserta AJ, Cochran K, Cohen L, Dewan A, Dickinson-Frevola S, Fenigstein L, et al. The Evolutionary Psychology of Breaking Informal Versus Formal Contracts: Effects of Group Size and Area of Upbringing. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111458

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeher, Glenn, Ethan Eisenberg, Michael DeMaio, Olivia Casa, Anthony J. Caserta, Katherine Cochran, Leah Cohen, Aliza Dewan, Stephanie Dickinson-Frevola, Lauryn Fenigstein, and et al. 2025. "The Evolutionary Psychology of Breaking Informal Versus Formal Contracts: Effects of Group Size and Area of Upbringing" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111458

APA StyleGeher, G., Eisenberg, E., DeMaio, M., Casa, O., Caserta, A. J., Cochran, K., Cohen, L., Dewan, A., Dickinson-Frevola, S., Fenigstein, L., Giboyeaux, C., Goren, M., Jerabek, E., Lieberstein, J., Marr, L., Staccio, B., & Tamayo, N. (2025). The Evolutionary Psychology of Breaking Informal Versus Formal Contracts: Effects of Group Size and Area of Upbringing. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111458