The Contextualized Impact of Ethnic-Racial Socialization on Black and Latino Youth’s Self-Esteem and Ethnic-Racial Identity

Abstract

1. Introduction

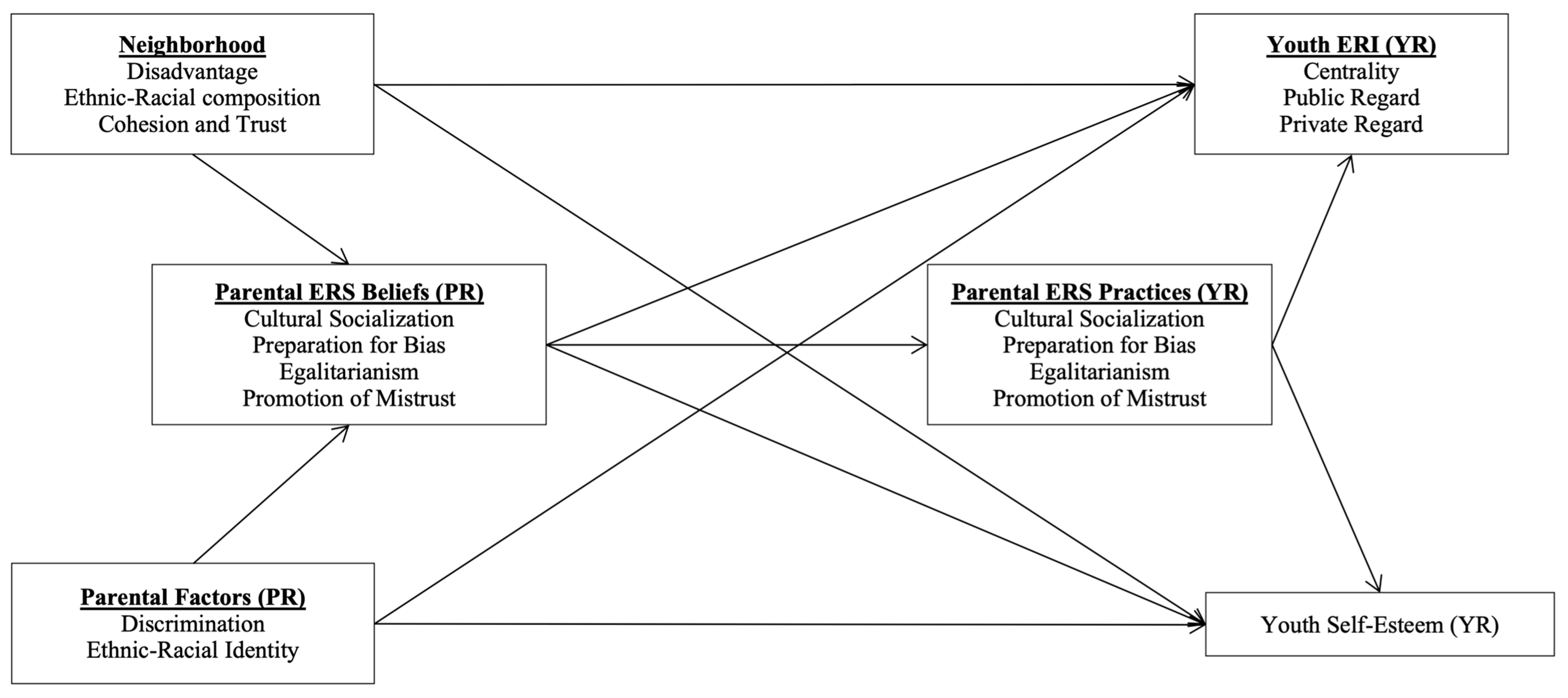

1.1. Theoretical Framework

1.2. Ethnic-Racial Socialization and the Self-System

1.3. Parental ERS Beliefs and Practices

1.4. Neighborhood, ERS, and Youth Self-System

1.5. Parental Cultural Stressors and Assets, ERS, and Youth Self-System

1.5.1. Cultural Stressors

1.5.2. Cultural Assets

1.6. Ethnic-Racial Group as a Moderator

1.7. Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Sample

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographics

2.3.2. Neighborhood Characteristics

2.3.3. Parental Cultural Factors2

2.3.4. Ethnic-Racial Socialization

2.3.5. Adolescent Outcomes

2.4. Data Analysis Plan

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.2. Structural Equation Modeling

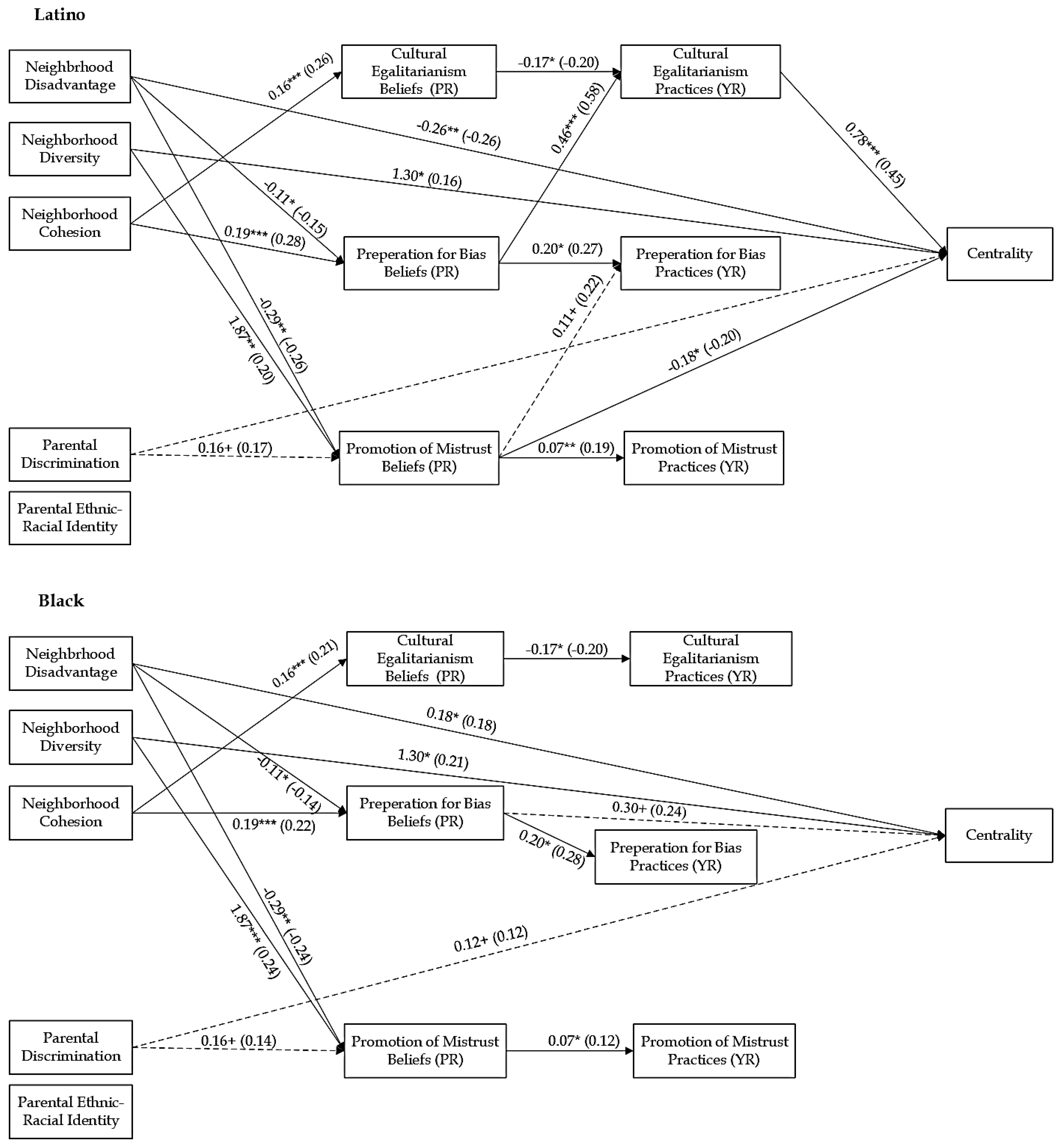

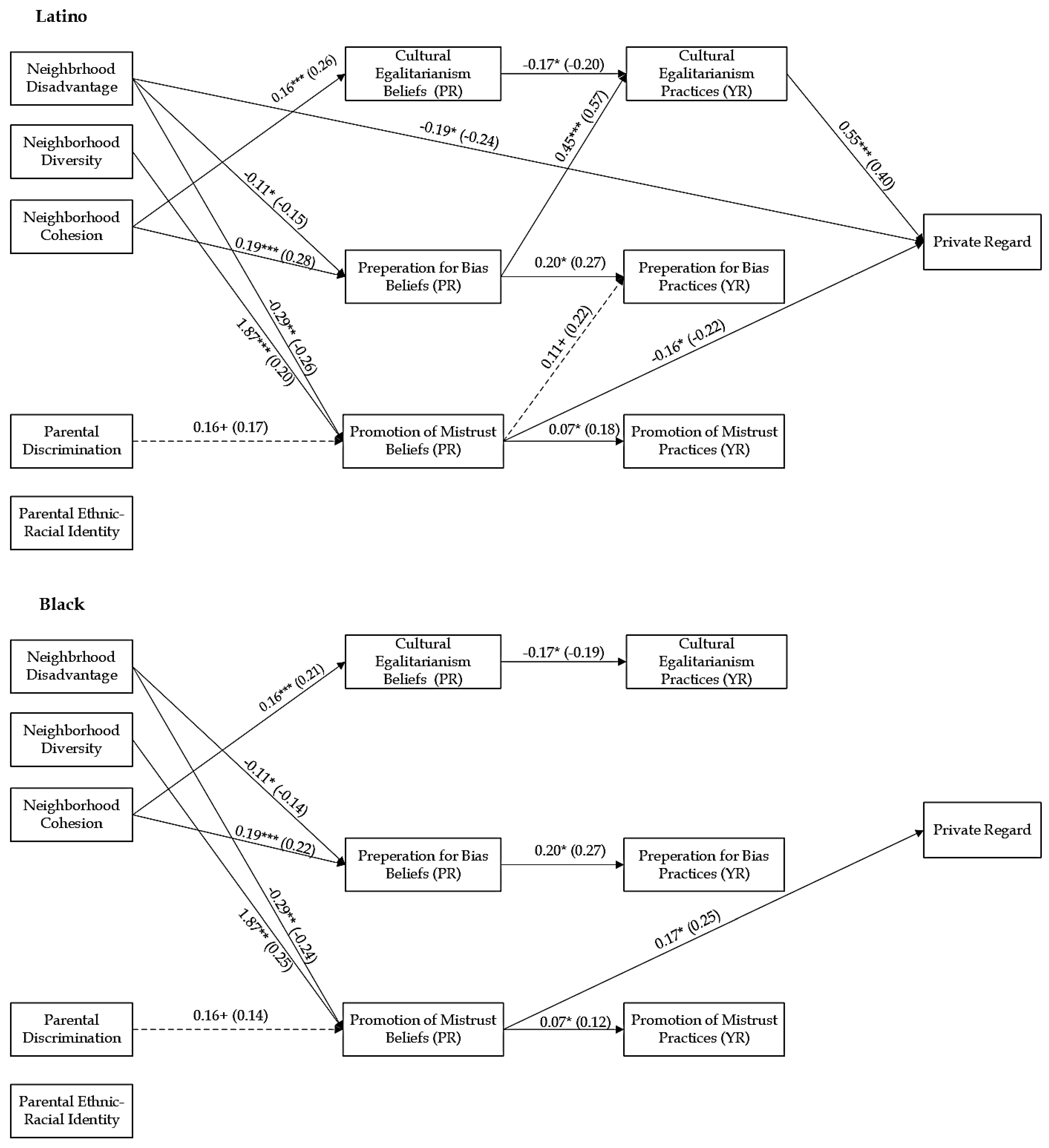

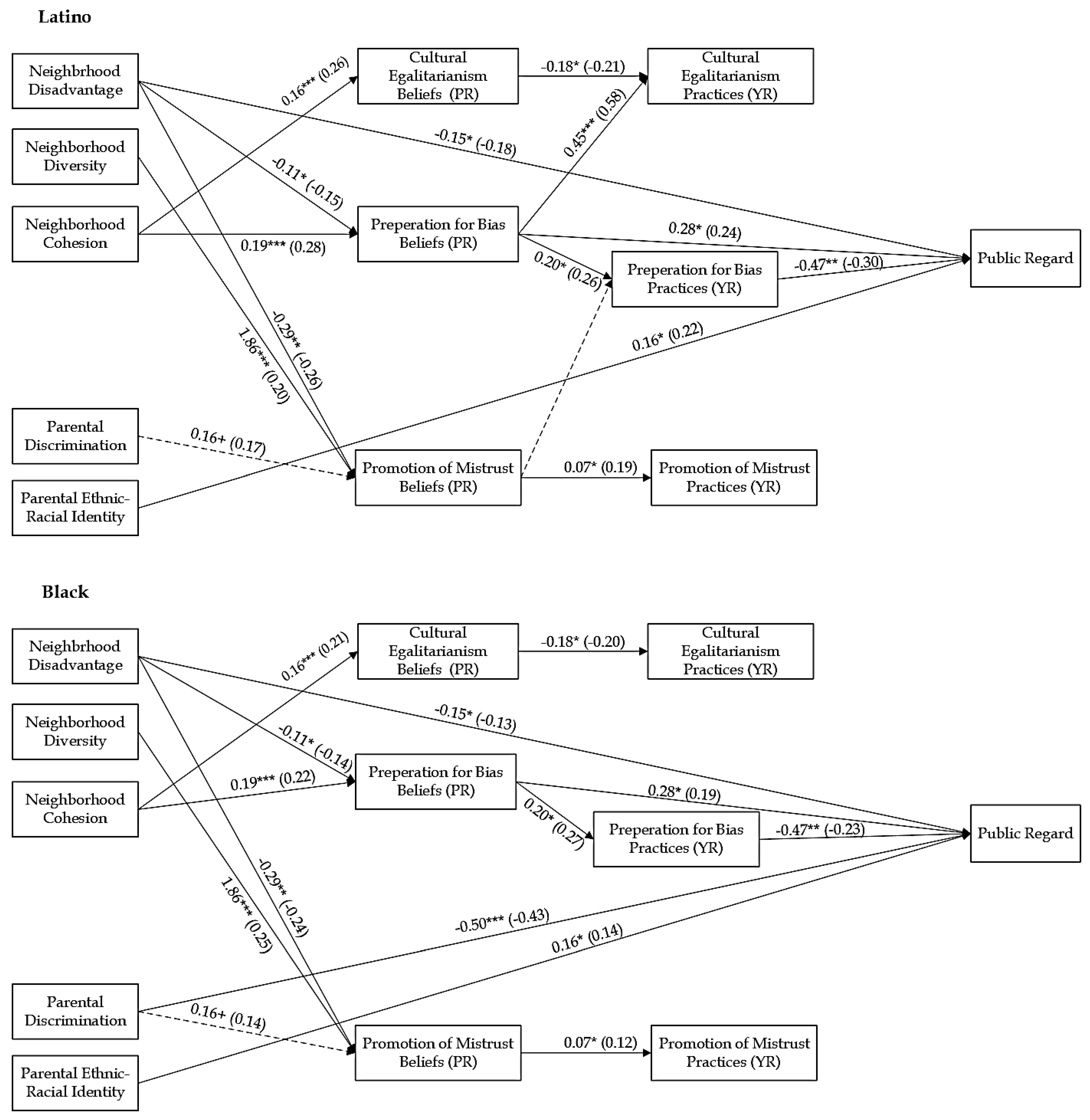

3.3. Direct Effects

3.3.1. Effects of Neighborhood Factors on ERS and Youth Self-System

3.3.2. Effects of Parental Cultural Factors on ERS and Youth Self-System

3.3.3. Effects of ERS Beliefs on ERS Practices and Youth Self-System

3.3.4. Effects of ERS Practices on Youth Self-System

3.4. Mediation Effects

3.4.1. Self-Esteem

3.4.2. Centrality

3.4.3. Private Regard

3.4.4. Public Regard

3.4.5. Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. ERS Beliefs and Practices and Youth’s Self-System

4.2. Neighborhood Factors, ERS, and Youth’s Self-System

4.3. Parental Cultural Factors, ERS, and Youth’s Self-System

4.4. Mediation

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

4.6. Policy and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The term parents is used inclusively to refer to any primary caregiver responsible for the daily parenting and care of the target child. This may include, but is not limited to, biological parents, adoptive parents, stepparents, or other guardians serving in a parental role. |

| 2 | All measures have been validated or shown to be reliable among Black and Latino populations. |

References

- Anderson, R. E., Johnson, N., Jones, S. C. T., Patterson, A., & Anyiwo, N. (2024). Racial socialization and black adolescent mental health and developmental outcomes: A critical review and future directions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 53(5), 709–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. E., McKenny, M. C., & Stevenson, H. C. (2018). EMBRace: Developing a racial socialization intervention to reduce racial stress and enhance racial coping among Black parents and adolescents. Family Process, 58(1), 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. E., & Stevenson, H. C. (2019). RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. American Psychologist, 74(1), 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, A. L., Yoo, H. C., & Yeh, C. J. (2018). What types of racial messages protect Asian American adolescents from discrimination? A latent interaction model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(2), 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayón, C., Nieri, T., & Ruano, E. (2020). Ethnic-racial socialization among Latinx families: A systematic review of the literature. Social Service Review, 94(4), 693–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. C., & Neville, H. A. (2014). Racial socialization, color-blind racial ideology, and mental health among black college students: An examination of an ecological model. Journal of Black Psychology, 40(2), 138–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bámaca, M. Y., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Shin, N., & Alfaro, E. C. (2005). Latino adolescents’ perception of parenting behaviors and self-esteem: Examining the role of neighborhood risk. Family Relations, 54(5), 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, A. O., Plunkett, S. W., Sands, T., & Bámaca-Colbert, M. Y. (2011). The relationship between Latino adolescents’ perceptions of discrimination, neighborhood risk, and parenting on self-esteem and depressive symptoms. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(7), 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, S., & Phillips, S. A. (2022). Mapping and making gangland: A legacy of redlining and enjoining gang neighbourhoods in Los Angeles. Urban Studies, 59(4), 750–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, J. M., Eldin, M. M., Golestani, S., Cardenas, T. C., Trust, M. D., Mery, M., Teixeira, P. G., DuBose, J., Brown, L. H., Bach, M., Robert, M., Ali, S., Salvo, D., & Brown, C. V. (2024). Structural racism, residential segregation, and exposure to trauma: The persistent impact of redlining. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 97(6), 891–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branje, S., de Moor, E. L., Spitzer, J., & Becht, A. I. (2021). Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: A decade in review. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 908–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. E., & Brooks, F. (2006). African American and Latino perceptions of cohesion in a multiethnic neighborhood. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(2), 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, C. M., & Chavous, T. (2011). RacialiIdentity, school racial climate, and school intrinsic motivation among African American youth: The importance of person–context congruence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(4), 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughy, M. O., Nettles, S. M., O’Campo, P. J., & Lohrfink, K. F. (2006). Neighborhood matters: Racial socialization of African American children. Child Development, 77(5), 1220–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavous, T. M., Bernat, D. H., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Caldwell, C. H., Kohn-Wood, L., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2003). Racial identity and academic attainment among African American adolescents. Child Development, 74(4), 1076–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophe, N. K., Stein, G. L., & Salcido, V. V. (2024). Parental ethnic-racial socializations messages direct and indirect associations with shift-and-persist coping among minoritized American adolescents. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 31(2), 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, M. M., Osborne, K. R., Walsdorf, A. A., Anderson, L. A., Caughy, M. O., & Owen, M. T. (2021). Holding both truths: Early dynamics of ethnic-racial socialization and children’s behavior adjustment in African American and Latinx families. Journal of Social Issues, 77(4), 987–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S. M., & McLoyd, V. C. (2011). Racial barrier socialization and the well-being of African American adolescents: The moderating role of mother–adolescent relationship quality. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(4), 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, F. L., Agi, A., Montoro, J. P., Medina, M. A., Miller-Tejada, S., Pinetta, B. J., Tran-Dubongco, M., & Rivas-Drake, D. (2020). Illuminating ethnic-racial socialization among undocumented Latinx parents and its implications for adolescent psychosocial functioning. Developmental Psychology, 56(8), 1458–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daga, S. S., & Raval, V. V. (2018). Ethnic–racial socialization, model minority experience, and psychological functioning among south Asian American emerging adults: A preliminary mixed-methods study. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 9(1), 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B. L., Smith-Bynum, M. A., Saleem, F. T., Francois, T., & Lambert, S. F. (2017). Racial socialization, private regard, and behavior problems in African American youth: Global self-esteem as a mediator. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(3), 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derlan, C. L., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Toomey, R. B., Jahromi, L. B., & Updegraff, K. A. (2016). Measuring cultural socialization attitudes and behaviors of Mexican-origin mothers with young children: A longitudinal investigation. Family Relations, 65(3), 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donato, K. M., Tolbert, C., Nucci, A., & Kawano, Y. (2008). Changing faces, changing places: The emergence of new nonmetropolitan immigrant gateways. In New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration (pp. 75–98). Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, A. S., HaRim Ahn, L., Coates, E. E., & Smith-Bynum, M. A. (2022). Observed dyadic racial socialization disrupts the association between frequent discriminatory experiences and emotional reactivity among Black adolescents. Child Development, 93(1), 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, A. S., Perry, N. B., Cavanaugh, A. M., & Leerkes, E. M. (2015). African American parents’ racial and emotion socialization profiles and young adults’ emotional adaptation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(3), 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, D., Lambert, S. F., Evans, M. K., & Zonderman, A. B. (2014). Neighborhood racial composition, racial discrimination, and depressive symptoms in African Americans. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(3–4), 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, G., Gonzales, N. A., & Fuligni, A. J. (2016). Parent discrimination predicts Mexican-American adolescent psychological adjustment 1 year later. Child Development, 87(4), 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. W. (2004). The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist, 59(2), 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M., & McDonald, A. (2023). Reconsidering family ethnic-racial socialization: Challenges, progress, and directions for future research. In D. P. Witherspoon, S. M. McHale, & V. King (Eds.), Family socialization, race, and inequality in the United States (pp. 217–229). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Flippen, C. A., & Parrado, E. A. (2015). Perceived discrimination among Latino immigrants in new destinations: The case of Durham, NC. Sociological Perspectives: SP: Official Publication of the Pacific Sociological Association, 58(4), 666–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Coll, C., Crnic, K., Lamberty, G., Wasik, B. H., Jenkins, R., García, H. V., & McAdoo, H. P. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, O. C., Witherspoon, D. P., & Bámaca, M. Y. (2025). Neighborhood conditions in a new destination context and Latine youth’s ethnic–racial identity: What’s gender got to do with It? Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagelskamp, C., & Hughes, D. L. (2014). Workplace discrimination predicting racial/ethnic socialization across African American, Latino, and Chinese families. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(4), 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, J. V., & Coleman, H. L. K. (2001). African American and white adolescents’ strategies for managing cultural diversity in predominantly White high schools. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30(3), 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Britt, A., Valrie, C. R., Kurtz-Costes, B., & Rowley, S. J. (2007). Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in African American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17(4), 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holloway, K., & Varner, F. (2021). Parenting despite discrimination: Does racial identity matter? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(4), 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hox, J. J., Maas, C. J. M., & Brinkhuis, M. J. S. (2010). The effect of estimation method and sample size in multilevel structural equation modeling. Statistica Neerlandica, 64(2), 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D. (2003). Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1–2), 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D., Hagelskamp, C., Way, N., & Foust, M. D. (2009a). The role of mothers’ and adolescents’ perceptions of ethnic-racial socialization in shaping ethnic-racial identity among early adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(5), 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D., Rivas, D., Foust, M., Hagelskamp, C., Gersick, S., & Way, N. (2008). How to catch a moonbeam: A mixed-methods approach to understanding ethnic socialization processes in ethnically diverse families. In S. M. Quintana, & C. McKown (Eds.), Handbook of race, racism, and the developing child (pp. 226–277). Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D., Rodriguez, J., Smith, E. P., Johnson, D. J., Stevenson, H. C., & Spicer, P. (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D., Witherspoon, D., Rivas-Drake, D., & West-Bey, N. (2009b). Received ethnic–racial socialization messages and youths’ academic and behavioral outcomes: Examining the mediating role of ethnic identity and self-esteem. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(2), 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D. L., Watford, J. A., & Del Toro, J. (2016). A transactional/ecological perspective on ethnic–racial identity, socialization, and discrimination. In S. S. Horn, M. D. Ruck, & L. S. Liben (Eds.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 51, pp. 1–41). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguley, J. P., Wang, M.-T., Vasquez, A. C., & Guo, J. (2019). Parental ethnic–racial socialization practices and the construction of children of color’s ethnic–racial identity: A research synthesis and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 145(5), 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J., & Witherspoon, D. P. (2025). Social context and family relationships: Neighborhoods and parenting. In N. C. Overall, J. A. Simpson, & J. A. Lavner (Eds.), Research handbook on couple and family relationships (pp. 374–390). Edward Elgar Publishing. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781035309269/book-part-9781035309269-35.xml (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Izzo, C., Weiss, L., Shanahan, T., & Rodriguez-Brown, F. (2000). Parental self-efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting practices and children’s socioemotional adjustment in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 20(1–2), 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, D. M., & MacPhee, D. (2017). Self-esteem and future orientation predict adolescents’ risk engagement. Journal of Early Adolescence, 37(3), 339–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jencks, C., & Mayer, S. E. (1990). The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. In L. E. Lynn Jr., & M. G. H. McGeary (Eds.), Inner-city poverty in the United States (pp. 111–186). National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R., & Soroka, S. (2003). Social capital in a multicultural society: The case of Canada. In P. Dekker, & E. M. Uslaner (Eds.), Social capital and participation in everyday life (pp. 30–44). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, J., Nishina, A., & Graham, S. (2006). Ethnic diversity and perceptions of safety in urban middle schools. Psychological Science, 17(5), 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiang, L., Christophe, N. K., Stein, G. L., Stevenson, H. C., Jones, S. C. T., Chan, M., & Anderson, R. E. (2023). Ethnic-racial identity and ethnic-racial socialization competency: How minoritized parents “walk the talk”. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 29(4), 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Y., Chen, S., Hou, Y., Zeiders, K. H., & Calzada, E. J. (2019). Parental socialization profiles in Mexican-origin families: Considering cultural socialization and general parenting practices. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(3), 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulish, A. L., Cavanaugh, A. M., Stein, G. L., Kiang, L., Gonzalez, L. M., Supple, A., & Mejia, Y. (2019). Ethnic–racial socialization in Latino families: The influence of mothers’ socialization practices on adolescent private regard, familism, and perceived ethnic–racial discrimination. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(2), 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechuga-Peña, S., & Brisson, D. (2018). Your family, your neighborhood: Results from a feasibility and acceptability study of parent engagement in subsidized project-based housing. Journal of Community Practice, 26(4), 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, T., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maereg, T. M., Glover, B. A., Im, J., Neal, A. J., McBride, M., Harris, A., & Witherspoon, D. P. (2024). Neighborhood effects. In W. Troop-Gordon, & E. W. Neblett (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (2nd ed., pp. 287–301). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrow, H. B. (2008). Hispanic immigration, black population size, and intergroup relations in the rural and small-town South. In New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration (pp. 211–248). Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Fuentes, S., Jager, J., & Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2021). The mediation process between Latino youths’ family ethnic socialization, ethnic-racial identity, and academic engagement: Moderation by ethnic-racial discrimination? Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(2), 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. S. (Ed.). (2008). New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Murry, V., Berkel, C., Brody, G., Miller, S., & Chen, Y. (2009). Linking parental socialization to interpersonal protective processes, academic self-presentation, and expectations among rural African American youth. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthéén. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett, E. W., Smalls, C. P., Ford, K. R., Nguyên, H. X., & Sellers, R. M. (2009). Racial socialization and racial identity: African American parents’ messages about race as precursors to identity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(2), 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S. C., Syed, M., Tran, A. G. T. T., Hu, A. W., & Lee, R. M. (2018). Pathways to ethnic-racial identity development and psychological adjustment: The differential associations of cultural socialization by parents and peers. Developmental Psychology, 54(11), 2166–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasco, M. C., White, R. M. B., Iida, M., & Seaton, E. K. (2021a). A prospective examination of neighborhood social and cultural cohesion and parenting processes on ethnic-racial identity among U.S. Mexican adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 57(5), 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasco, M. C., White, R. M. B., & Seaton, E. K. (2021b). A systematic review of neighborhood ethnic–racial compositions on cultural developmental processes and experiences in adolescence. Adolescent Research Review, 6(2), 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, S. C., Brodish, A. B., Malanchuk, O., Banerjee, M., & Eccles, J. S. (2014). Racial/ethnic socialization and identity development in Black families: The role of parent and youth reports. Developmental Psychology, 50(7), 1897–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phinney, J. S. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phinney, J. S. (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7(2), 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, N., Walton, J., White, F., Kowal, E., Baker, A., & Paradies, Y. (2014). Understanding the complexities of ethnic-racial socialization processes for both minority and majority groups: A 30-year systematic review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 43, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Drake, D., Hughes, D., & Way, N. (2009). A preliminary analysis of associations among ethnic-racial socialization, ethnic discrimination, and ethnic identity among urban sixth graders. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19(3), 558–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Drake, D., Seaton, E. K., Markstrom, C., Quintana, S., Syed, M., Lee, R. M., Schwartz, S. J., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., French, S., Yip, T., & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85(1), 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas-Drake, D., & Witherspoon, D. (2013). Racial identity from adolescence to young adulthood: Does prior neighborhood experience matter? Child Development, 84(6), 1918–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J., Umaña-Taylor, A., Smith, E. P., & Johnson, D. J. (2009). Cultural processes in parenting and youth outcomes: Examining a model of racial-ethnic socialization and identity in diverse populations. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(2), 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Salcido, V. V., & Stein, G. L. (2024). Proactive coping with discrimination: A mediator between ethnic-racial socialization and Latinx youth’s internalizing symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 34(1), 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, F. T., English, D., Busby, D. R., Lambert, S. F., Harrison, A., Stock, M. L., & Gibbons, F. X. (2016). The impact of African American parents’ racial discrimination experiences and perceived neighborhood cohesion on their racial socialization practices. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(7), 1338–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L. E., & Varner, F. (2023). Who, what, and where? How racial composition and gender influence the association between racial discrimination and racial socialization messages. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 29(4), 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, E. K., Caldwell, C. H., Sellers, R. M., & Jackson, J. S. (2008). The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1288–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, R. M., Copeland-Linder, N., Martin, P. P., & Lewis, R. L. (2006). Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(2), 187–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, R. M., Smith, M. A., Shelton, J. N., Rowley, S. A. J., & Chavous, T. M. (1998). Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(1), 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas: A study of rates of delinquency in relation to differential characteristics of local communities in American cities. University of Chicago Press. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=M4Nc0AEACAAJ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Simon, C. (2021). The role of race and ethnicity in parental ethnic-racial socialization: A scoping review of research. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(1), 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E. H. (1949). Measurement of diversity. Nature, 163(4148), 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E. P., Yzaguirre, M. M., Dwanyen, L., & Wieling, E. (2022). Culturally relevant parenting approaches among African American and Latinx children and families: Toward resilient, strengths-based, trauma-informed practices. Adversity and Resilience Science, 3(3), 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. A., McDonald, A., Wei, W., Johnson, S. A., Adeji, D., & Witherspoon, D. P. (2022). Embracing race, resisting oppression: African American parents as experienced guides for navigating racial oppression. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 32(1), 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Bynum, M. A. (2023). The theory of racial socialization in action for Black adolescents and their families. In D. P. Witherspoon, & G. L. Stein (Eds.), Diversity and developmental science (pp. 59–91). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M. B. (1995). Old issues and new theorizing about African American youth: A phenomenological variant of ecological systems theory. In R. L. Taylor (Ed.), Black youth: Perspectives on their status in the United States (pp. 37–70). Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, G. L., Christophe, N. K., Castro-Schilo, L., Gomez Alvarado, C., & Robins, R. (2023). Longitudinal links between maternal cultural socialization, peer ethnic-racial discrimination, and ethnic-racial pride in Mexican American youth. Child Development, 94(3), 752–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, G. L., Coard, S. I., Gonzalez, L. M., Kiang, L., & Sircar, J. K. (2021). One talk at a time: Developing an ethnic-racial socialization intervention for Black, Latinx, and Asian American families. Journal of Social Issues, 77(4), 1014–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, H. C., & Arrington, E. G. (2009). Racial/ethnic socialization mediates perceived racism and the racial identity of African American adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(2), 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamasa, E. J., Fraser, A. M., & Rogers, A. A. (2024). Main and interactive effects of discrimination, parent racial/ethnic socialization, and internalizing symptomology on BIPOC teens’ ethnic-racial identity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 34(3), 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, A. J., & Hill, N. E. (2020). Ethnic–racial socialization in the family: A decade’s advance on precursors and outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 1(82), 244–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varner, F. A., Mandara, J., Scott, L. E., & Murray, C. B. (2022). The relationship between neighborhood racial composition and African American parents’ racial socialization. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(2), 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Yip, T. (2020). Parallel changes in ethnic/racial discrimination and identity in high school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(7), 1517–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R. M. B., Knight, G. P., Jensen, M., & Gonzales, N. A. (2018). Ethnic socialization in neighborhood contexts: Implications for ethnic attitude and identity development among Mexican-origin adolescents. Child Development, 89(3), 1004–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R. M. B., Witherspoon, D. P., Wei, W., Zhao, C., Pasco, M. C., Maereg, T. M., & PLACE Development Working Group. (2021). Adolescent development in context: A decade review of neighborhood and activity space research. Journal of Research on Adolescence: The Official Journal of the Society for Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 944–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White-Johnson, R. L., Ford, K. R., & Sellers, R. M. (2010). Parental racial socialization profiles: Association with demographic factors, racial discrimination, childhood socialization, and racial identity. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(2), 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C. D., Byrd, C. M., Quintana, S. M., Anicama, C., Kiang, L., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Calzada, E. J., Pabón Gautier, M., Ejesi, K., Tuitt, N. R., Martinez-Fuentes, S., White, L., Marks, A., Rogers, L. O., & Whitesell, N. (2020). A lifespan model of ethnic-racial identity. Research in Human Development, 17(2–3), 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. R., Yu, Y., Jackson, J. S., & Anderson, N. B. (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, E. N. (2012). Learning race, learning place: Shaping racial identities and ideas in African American childhoods. Rutgers University Press. Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/asulib-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1028978 (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- Witherspoon, D. P., May, E. M., McDonald, A., Boggs, S., & Bámaca-Colbert, M. (2019). Parenting within residential neighborhoods: A pluralistic approach with African American and Latino families at the center. In D. A. Henry, E. Votruba-Drzal, & P. Miller (Eds.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 57, pp. 235–279). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, D. P., Smalls Glover, C., Wei, W., & Hughes, D. L. (2022). Neighborhood--level predictors of African American and Latinx parents’ ethnic–racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology, 69(1–2), 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, D. P., Wei, W., May, E. M., Boggs, S., Chancy, D., Bámaca-Colbert, M. Y., & Bhargava, S. (2021). Latinx youth’s ethnic-racial identity in context: Examining ethnic-racial socialization in a new destination area. Journal of Social Issues, 77(4), 1234–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, D. P., White, R. M. B., Nair, R., Maereg, T. M., & Wei, W. (2023). Fertile ground for sociocultural responsivity: Schools and neighborhoods as promotive and inhibiting environments. In D. P. Witherspoon, & G. L. Stein (Eds.), Diversity and developmental science: Bridging the gaps between research, practice, and policy (pp. 167–195). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, B., Maglalang, D. D., Ko, S., Park, M., Choi, Y., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2020). Racial discrimination, ethnic-racial socialization, and cultural identities among Asian American youths. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 26(4), 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latino (N = 95) | Black (N = 89) | t or χ2 (df) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Frequency (Valid %) or Mean (SD) | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Parent | |||

| Age | 39.81 (8.88) | 41.52 (9.44) | −1.03 (120) |

| Marital status | 15.1 *** (2) | ||

| Not married or cohabiting | 27.3% a | 59.4% b | |

| Married or cohabitating | 39.0% | 25.0% | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 33.8% a | 15.6% b | |

| Educational level | 15.48 *** (3) | ||

| Less than high school | 27.4% a | 3.2% b | |

| High school degree | 38.4% | 43.5% | |

| Some postsecondary education | 23.3% a | 40.3% b | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 11.0% | 12.9% | |

| Family income | |||

| Less than USD 10,000 | 44.6% | 30.4% | 15.57 ** (4) |

| USD 10,001–20,000 | 33.9% a | 14.3% b | |

| USD 20,001–30,000 | 8.9% | 17.9% | |

| USD 30,001–40,000 | 3.6% a | 19.6% b | |

| More than USD 41,000 | 8.9% | 17.9% | |

| Family income-to-needs ratio | 0.74 (0.91) | 1.20 (1.12) | −2.32 * (120) |

| Years living in current neighborhood | 7.21 (6.77) | 10.5 (10.23) | −2.14 * (120) |

| Adolescent | |||

| Age | 13.33 (1.95) | 13.44 (1.87) | −0.42 (182) |

| Gender (% female) | 55.4% | 59.8% | −0.58 (177) |

| Study Variables | |||

| Neighborhood disadvantage | −0.11 (0.85) | 0.12 (0.74) | −1.95 + (182) |

| Neighborhood diversity | 0.57 (0.11) | 0.57 (0.12) | −0.35 (182) |

| Neighborhood cohesion | 2.35 (0.93) | 2.69 (0.66) | −2.88 ** (182) |

| Parental discrimination | 2.03 (1.04) | 1.95 (0.76) | 0.65 (178) |

| Parental ethnic-racial identity | 3.60 (0.99) | 3.70 (0.86) | −0.62 (135) |

| Cultural-egalitarianism beliefs (PR) | 3.59 (0.51) | 3.57 (0.60) | −0.28 (178) |

| Preparation for bias beliefs (PR) | 3.47 (0.66) | 3.62 (0.53) | −1.53 (140) |

| Promotion of mistrust beliefs (PR) | 3.02 (0.96) | 2.14 (0.91) | 6.33 *** (178) |

| Cultural-egalitarianism practices (YR) | 2.28 (0.49) | 2.43 (0.43) | −2.08 * (145) |

| Preparation for bias practices (YR) | 1.66 (0.48) | 1.66 (0.42) | 0.11 (145) |

| Promotion of mistrust practices (YR) | 1.13 (0.33) | 1.20 (0.51) | −0.90 (145) |

| Youth self-esteem | 1.95 (0.53) | 2.23 (0.57) | −3.24 *** (165) |

| Youth centrality | 3.89 (0.88) | 4.02 (0.75) | −1.07 (178) |

| Youth private regard | 4.22 (0.69) | 4.35 (0.61) | −1.28 (178) |

| Youth public regard | 3.42 (0.73) | 3.19 (0.92) | 1.79 + (178) |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Adolescent Age | -- | −0.03 | −0.15 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.12 | −0.01 | −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.17 | 0.04 | −0.12 | −0.09 | 0.14 | 0.17 | −0.10 |

| 2. Family Income | 0.25 * | -- | −0.29 * | −0.06 | 0.19 | 0.28 * | 0.15 | −0.04 | 0.10 | −0.29 * | 0.22 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| 3. Neighborhood Disadvantage | 0.18 | −0.18 | -- | 0.32 ** | −0.06 | 0.16 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.19 | −0.09 | −0.16 | 0.09 | 0.10 | −0.26 * | −0.22 * | −0.27 ** | −0.28 ** |

| 4. Neighborhood Diversity | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.22 * | -- | 0.06 | −0.19 | −0.24 * | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.22 * | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.12 |

| 5. Neighborhood Cohesion | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.23 * | -- | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.29 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.07 | 0.23 * | 0.24 * | 0.14 | −0.12 | 0.01 | 0.17 | −0.03 |

| 6. Parental Discrimination | −0.09 | −0.16 | 0.01 | −0.13 | 0.01 | -- | −0.25 * | −0.27 ** | −0.16 | 0.09 | −0.18 | 0.11 | 0.06 | −0.23 * | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.14 |

| 7. Parental Ethnic-Racial Identity | −0.13 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.12 | −0.06 | -- | 0.14 | 0.12 | −0.09 | 0.15 | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.21 * |

| 8. Cultural-Egalitarianism Beliefs (PR) | −0.37 ** | 0.10 | −0.16 | 0.06 | 0.22 * | 0.11 | 0.17 | -- | 0.72 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.20 | 0.10 | −0.04 | 0.14 | −0.13 | −0.01 | 0.11 |

| 9. Preparation for Bias Beliefs (PR) | −0.12 | 0.18 | −0.11 | 0.02 | 0.27 * | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.68 ** | -- | 0.31 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.27 * | −0.06 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| 10. Promotion of Mistrust Beliefs (PR) | −0.17 | 0.00 | −0.16 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.18 | −0.07 | 0.32 ** | 0.32 ** | -- | −0.03 | 0.20 | 0.16 | −0.10 | −0.22 * | −0.19 | 0.06 |

| 11. Cultural-Egalitarianism Practices (YR) | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.19 | 0.06 | −0.12 | 0.08 | 0.07 | −0.25 | −0.16 | 0.04 | -- | 0.29 ** | −0.14 | 0.26 * | 0.42 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.08 |

| 12. Preparation for Bias Practices (YR) | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.09 | −0.19 | −0.18 | −0.11 | −0.22 | −0.01 | -- | 0.20 | −0.16 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.27 * |

| 13. Promotion of Mistrust Practices (YR) | 0.04 | −0.27 | 0.17 | 0.11 | −0.12 | 0.10 | −0.10 | −0.29 * | −0.32 * | −0.12 | −0.27 * | 0.21 | -- | −0.30 ** | −0.13 | −0.15 | −0.08 |

| 14. Youth Self-Esteem | 0.09 | 0.21 | −0.14 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.14 | −0.08 | −0.31 * | -- | 0.26 * | 0.32 ** | 0.20 |

| 15. Youth Centrality | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.25 * | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.24 * | 0.18 | −0.09 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.15 | -- | 0.71 ** | 0.03 |

| 16. Youth Private Regard | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.11 | −0.08 | 0.13 | 0.23 * | 0.27 * | −0.13 | 0.09 | −0.07 | 0.22 | 0.63 ** | -- | 0.17 |

| 17. Youth Public Regard | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.20 | 0.02 | −0.11 | −0.40 ** | 0.21 | −0.02 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.20 | −0.27 * | −0.24 | 0.29 * | −0.03 | −0.08 | -- |

| Model | Pathway Freed | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA (90% CI) | ∆χ2 from Previous Models | ∆df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Esteem | |||||||||

| 1. Unconstrained | 80.29 | 70 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.07 | 0.02 (0.00, 0.08) | |||

| 2. Constrained | 135.17 | 105 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.10 | 0.06 (0.02, 0.08) | 54.87 *** | 35 | |

| 3. Model 1 | PFB Beliefs (PR) → CSEgal Practices (YR) | 118.48 | 104 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.04 (0.00, 0.07) | 16.69 *** | 1 |

| 4. Model 2 | PMT Beliefs (PR) → PFB Practices (YR) | 112.13 | 103 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 0.03 (0.00, 0.06) | 6.35 * | 1 |

| 5. Model 3 | N Disadvantage → Self-Esteem | 108.14 | 102 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.09 | 0.03 (0.00, 0.61) | 3.99 * | 1 |

| Centrality | |||||||||

| 1. Unconstrained | 73.00 | 70 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.07 | 0.02 (0.00, 0.07) | |||

| 2. Constrained | 148.74 | 105 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.10 | 0.07 (0.04, 0.09) | 75.74 *** | 35 | |

| 3. Model 1 | PFB Beliefs (PR) → CSEgal Practices (YR) | 132.43 | 104 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.10 | 0.06 (0.02, 0.08) | 16.31 *** | 1 |

| 4. Model 2 | CSEgal Practices (YR) → Centrality | 120.43 | 103 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.09 | 0.04 (0.00, 0.07) | 12.00 ** | 1 |

| 5. Model 3 | N Disadvantage → Centrality | 113.90 | 102 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.09 | 0.04 (0.00, 0.07) | 6.54 * | 1 |

| 6. Model 4 | PMT Beliefs (PR) → Centrality | 106.44 | 101 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.08 | 0.02 (0.00, 0.06) | 7.46 ** | 1 |

| 7. Model 5 | PMT Beliefs (PR) → PFB Practices (YR) | 99.98 | 100 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 (0.00, 0.06) | 6.46 * | 1 |

| 8. Model 6 | PFB Beliefs (PR) → Centrality | 95.17 | 99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 (0.00, 0.05) | 4.81 * | 1 |

| Private Regard | |||||||||

| 1. Unconstrained | 72.31 | 70 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.07 | 0.02 (0.00, 0.06) | |||

| 2. Constrained | 146.50 | 105 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.07 (0.04, 0.09) | 74.19 *** | 35 | |

| 3. Model 1 | PFB Beliefs (PR) → CSEgal Practices (YR) | 130.18 | 104 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.10 | 0.05 (0.01, 0.08) | 16.32 *** | 1 |

| 4. Model 2 | CSEgal Practices (YR) → Private Regard | 118.27 | 103 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.04 (0.00, 0.07) | 11.91 ** | 1 |

| 5. Model 3 | PMT Beliefs (PR) → Private Regard | 110.20 | 102 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.09 | 0.03 (0.00, 0.06) | 8.07 ** | 1 |

| 6. Model 4 | N Disadvantage → Private Regard | 102.06 | 101 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.01 (0.00, 0.06) | 8.14 ** | 1 |

| 7. Model 5 | PMT Beliefs (PR) → PFB Practices (YR) | 95.82 | 100 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 (0.00, 0.05) | 6.24 * | 1 |

| Public Regard | |||||||||

| 1. Unconstrained | 73.93 | 70 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.07 | 0.03 (0.00, 0.07) | |||

| 2. Constrained | 136.08 | 105 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.10 | 0.06 (0.02, 0.08) | 62.14 ** | 35 | |

| 3. Model 1 | PFB Beliefs (PR) → CSEgal Practices (YR) | 119.85 | 104 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.09 | 0.04 (0.00, 0.07) | 16.23 ** | 1 |

| 4. Model 2 | P Discrimination → Public Regard | 107.19 | 103 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.08 | 0.02 (0.00, 0.06) | 12.66 ** | 1 |

| 5. Model 3 | PMT Beliefs (PR) → PFB Practices (YR) | 101.16 | 102 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.08 | 0.00 (0.00, 0.05) | 6.02 * | 1 |

| Variables | Model 1: Self-Esteem | Model 2: Centrality | Model 3: Private Regard | Model 4: Public Regard | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latino | Black | Latino | Black | Latino | Black | Latino | Black | |

| B [95% CI] | B [95% CI] | B [95% CI] | B [95% CI] | |||||

| N Disadvantage → | ||||||||

| PFB Beliefs (PR) | −0.01 [−0.06, 0.004] | 0.02 [−0.01, 0.08] | −0.03 [−0.11, −0.002] a | −0.01 [−0.06, 0.01] | −0.03 [−0.10, −0.004] a | |||

| PMT Beliefs (PR) | 0.02 [−0.003, 0.06] | 0.05 [0.01, 0.13] a | −0.02 [−0.09, 0.02] | 0.05 [0.01, 0.12] a | −0.05 [−0.12, −0.01] a | −0.03 [−0.10, 0.003] b | ||

| PFB (PR) → CSEgal (YR) | −0.01 [−0.04, −0.001] a | 0.001 [−0.002, 0.10] | −0.04 [−0.12, −0.01] a | −0.001 [−0.02, 0.002] | −0.03 [−0.08, −0.01] a | −0.001 [−0.02, 0.002] | −0.01[−0.04, 0.00] b | 0.001 [−0.002, 0.01] |

| PFB (PR) → PFB (YR) | 0.003 [0.00, 0.02] | −0.002 [−0.02, 0.002] | 0.00 [−0.01, 0.004] | 0.01 [0.001, 0.04] a | ||||

| PMT (PR) → PFB (YR) | 0.004 [0.00, 0.02] | −0.003 [−0.02, 0.001] | −0.002 [−0.02, 0.01] | 0.002 [−0.004, 0.02] | 0.00 [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.00 [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.01 [0.002, 0.04] a | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.002] |

| PMT (PR) → PMT (YR) | 0.004 [0.001, 0.02]a | 0.003 [−0.001, 0.02] | 0.002 [0.00, 0.01] | 0.001 [−0.01, 0.01] | ||||

| Total Indirect | 0.004 [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.01 [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.05 [−0.01, 0.13] | −0.05 [−0.13, −0.002] a | 0.02 [−0.03, 0.09] | −0.06 [−0.13, −0.02] a | −0.04 [−0.10, 0.01] | −0.05 [−0.12, −0.01] a |

| N Diversity → | ||||||||

| PMT Beliefs (PR) | −0.12 [−0.36, 0.03] | −0.33 [−0.80, −0.04] a | 0.14 [−0.13, 0.55] | −0.30 [−0.69, −0.07] a | 0.31 [0.07, 0.72] a | 0.20 [−0.03, 0.61] b | ||

| PMT (PR) →PFB (YR) | −0.03 [−0.10, 0.002] b | 0.02 [−0.01, 0.10] | 0.02 [−0.04, 0.13] | −0.01 [−0.14, 0.03] | 0.003 [−0.04, 0.08] | −0.003 [−0.07, 0.04] | −0.09 [−0.28, −0.01] a | 0.08 [−0.02, 0.26] |

| PMT (PR) →PMT (YR) | −0.03 [−0.09, −0.01] a | −0.02 [−0.10, 0.01] | −0.02 [−0.07, 0.004] | −0.01 [−0.06, 0.04] | ||||

| Total Indirect | −0.17 [−0.46, 0.03] b | −0.12 [−0.40, 0.06] | −0.46 [−1.01, −0.10] a | 0.09 [−0.31, 0.52] | −0.38 [−0.85, −0.09] a | 0.30 [0.03, 0.69] a | 0.04 [−0.25, 0.42] | 0.21 [−0.08, 0.65] |

| N Cohesion → | ||||||||

| CSEgal Beliefs (PR) | 0.01 [−0.03, 0.04] | −0.02 [−0.08, 0.02] | −0.01 [−0.05, 0.02] | −0.04 [−0.10, 0.01] b | ||||

| PFB Beliefs (PR) | 0.02 [−0.01, 0.08] | −0.03 [−0.10, 0.03] | 0.06 [0.001, 0.15] a | 0.02 [−0.02, 0.07] | 0.05 [0.01, 0.14] a | |||

| PMT Beliefs (PR) | −0.01 [−0.03, 0.003] | −0.02 [−0.06, 0.004] | 0.01 [−0.01, 0.04] | −0.02 [−0.06, 0.003] | 0.02 [−0.003, 0.05] | 0.01 [−0.003, 0.04] | ||

| CSEgal (PR)→ CSEgal (YR) | −0.01 [−0.02, −0.001] a | −0.02 [−0.07, −0.004] a | 0.01 [−0.004, 0.03] | −0.02 [−0.04, −0.003] a | 0.01 [−0.001, 0.03] | −0.01 [−0.02, 0.00] | ||

| CSEgal (PR)→ PFB (YR) | 0.004 [0.00, 0.02] | −0.002 [−0.02, 0.01] | 0.00 [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.01 [0.00, 0.04] b | ||||

| PFB (PR) → CSEgal (YR) | 0.02 [0.004, 0.05] a | −0.001 [−0.01, 0.01] | 0.07 [0.03, 0.16] a | 0.002 [−0.01, 0.03] | 0.05 [0.02, 0.11] a | 0.002 [−0.001, 0.02] | 0.02 [−0.002, 0.06] b | −0.001 [−0.02, 0.01] |

| PFB (PR) →PFB (YR) | −0.01 [−0.02, 0.00] | 0.003 [−0.01, 0.02] | 0.001 [−0.01, 0.02] | −0.02 [−0.06, −0.003] a | ||||

| Total Indirect | 0.03 [0.002, 0.08] a | 0.02 [−0.01, 0.05] | −0.02 [−0.08, 0.04] | 0.06 [0.01, 0.13] a | 0.02 [−0.03, 0.08] | 0.03 [−0.01, 0.09] | 0.03 [−0.01, 0.09] | 0.02 [−0.03, 0.07] |

| P Discrimination → | ||||||||

| PMT Beliefs (PR) → | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.003] | −0.03 [−0.09, 0.00] b | 0.01 [−0.01, 0.06] | −0.03 [−0.08, −0.001] a | 0.03 [0.001, 0.08] a | 0.02 [−0.003, 0.07] | ||

| Total Indirect | −0.02 [−0.06, 0.02] | −0.01 [−0.05, 0.02] | −0.02 [−0.08, 0.04] | 0.02 [−0.04, 0.08] | −0.02 [0.08, 0.03] | 0.03 [−0.02, 0.08] | 0.02 [−0.03, 0.07] | 0.03 [−0.01, 0.09] |

| P ERI → | ||||||||

| CSEgal (PR) → CSEgal (YR) | −0.003 [−0.01, 0.00] | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.00] b | 0.003 [−0.001, 0.02] | −0.01 [−0.03, 0.00] b | 0.003 [0.00, 0.02] | −0.002 [−0.01, 0.00] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McDonald, A.R.; Glover, B.A.; Goldstein, O.C.; Witherspoon, D.P. The Contextualized Impact of Ethnic-Racial Socialization on Black and Latino Youth’s Self-Esteem and Ethnic-Racial Identity. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111437

McDonald AR, Glover BA, Goldstein OC, Witherspoon DP. The Contextualized Impact of Ethnic-Racial Socialization on Black and Latino Youth’s Self-Esteem and Ethnic-Racial Identity. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111437

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcDonald, Ashley R., Briah A. Glover, Olivia C. Goldstein, and Dawn P. Witherspoon. 2025. "The Contextualized Impact of Ethnic-Racial Socialization on Black and Latino Youth’s Self-Esteem and Ethnic-Racial Identity" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111437

APA StyleMcDonald, A. R., Glover, B. A., Goldstein, O. C., & Witherspoon, D. P. (2025). The Contextualized Impact of Ethnic-Racial Socialization on Black and Latino Youth’s Self-Esteem and Ethnic-Racial Identity. Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111437