Development and Validation of Social Trust Scale for Chinese Adolescents (STS-CA)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Social Trust Structure

1.2. Overview of Social Trust Measurement

1.3. The Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Scale Development

2.2.1. Item Generation

2.2.2. Content Validity Assessment

2.3. Criterion-Related Validity Measures

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Item Analysis

3.3. Validity Analysis

3.3.1. EFA

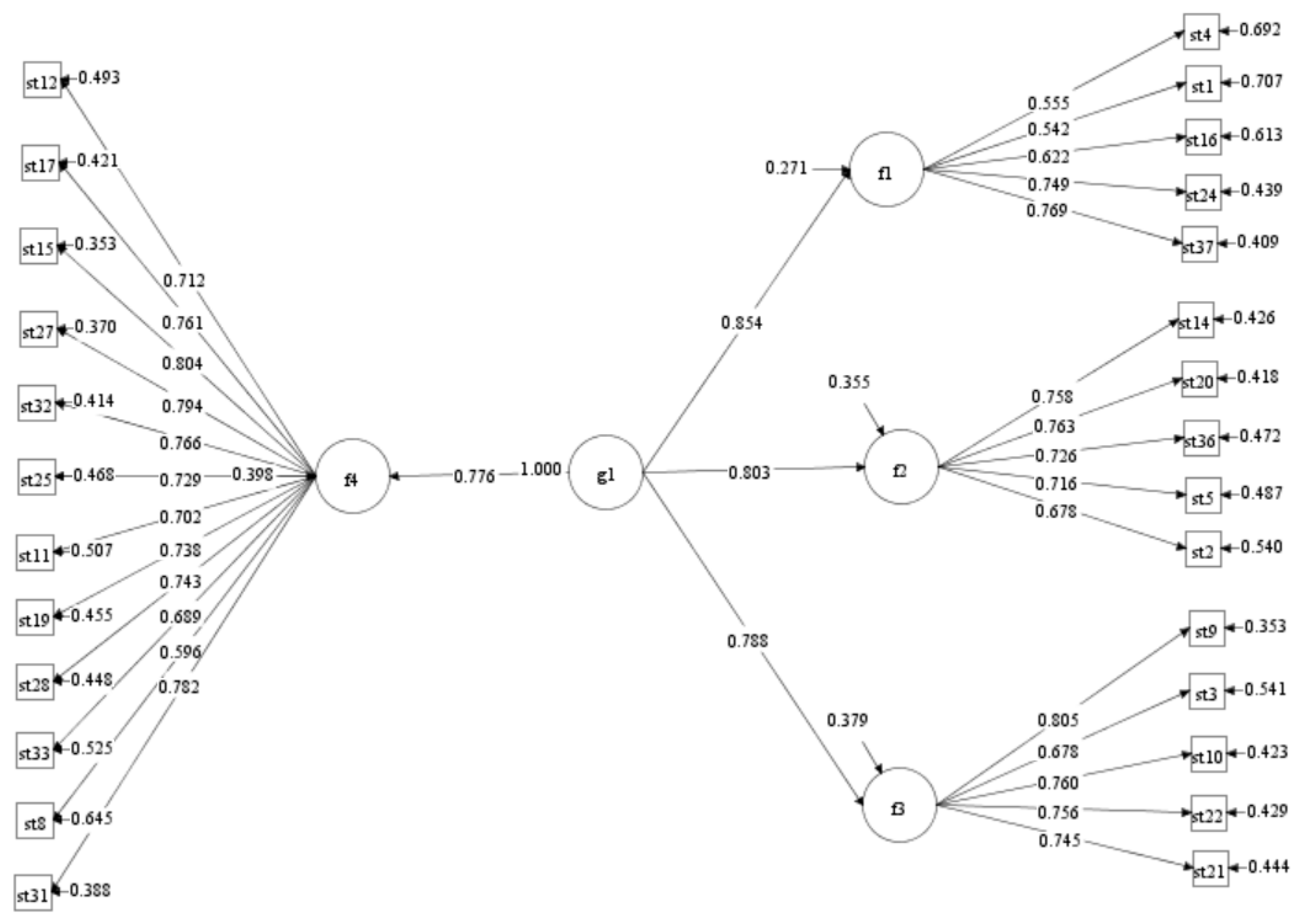

3.3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

3.3.3. Criterion-Related Validity and Reliability Analysis

3.3.4. Measurement Equivalence Across Groups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. The 27-Item Chinese Adolescents Social Trust Questionnaire

References

- Abdelzadeh, A., & Lundberg, E. (2017). Solid or flexible? Social trust from early adolescence to young adulthood. Scandinavian Political Studies, 40(2), 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C. Y. (2006). An analysis of the basic forms of social trust. Henan Social Sciences, (1), 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A., Barker, E. D., & Rahman, Q. (2022). Development and psychometric validation of the sexual fantasies and behaviors inventory. Psychological Assessment, 34(3), 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhey, J., Newton, K., & Welzel, C. (2011). How general is trust in “most people”? Solving the radius of trust problem. American Sociological Review, 76(5), 786–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R. F., & Thorpe, C. T. (2021). Scale development: Theory and applications (5th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A. M., & Revelle, W. (2008). Survey and behavioral measurements of interpersonal trust. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(6), 1585–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X. (2008). From the soil: The foundations of Chinese society. People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, M., & Kessler, A. (2010). Cooperation, trust and performance–empirical results from three countries. British Journal of Management, 21(2), 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 10(6), 269–314. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, C. A., & Stout, M. (2010). Developmental patterns of social trust between early and late adolescence: Age and school climate effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(3), 748–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D. I., Scheinkman, J. A., & Soutter, C. L. (2000). Measuring trust. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 811–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M. (2015). Research on the trust issues of college students in the context of social transformation. Henan Social Sciences, 23(4), 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30(2), 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhe, N. (2014). Understanding the multilevel foundation of social trust in rural China: Evidence from the China General Social Survey. Social Science Quarterly, 95(2), 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C., & Svendsen, G. T. (2011). Giving money to strangers: European welfare states and social trust. International Journal of Social Welfare, 20(1), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X. H., Shen, Z. Z., & Zhang, N. N. (2010). Analysis of the reliability and validity of questionnaires. Modern Preventive Medicine, 37(3), 429–431. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, O. Y. (2019). Social trust and economic development: The case of South Korea. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, R. D., & Valero-Mora, P. (2007). Determining the number of factors to retain in EFA: An easy-to-use computer program for carrying out parallel analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 12(1), 2. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. (2014). Research on donation attitude of college students and its relationship with social trust [Master’s thesis, Chongqing University]. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., Tang, L., Lai, Y. H., & Liu, J. (2025). Interpersonal trust and depression in female adolescents: Negative attributional style and self-esteem as mediators. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 53(2), e13842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W. (2019). Questionnaire development and measurement of adolescent social trust [Master’s thesis, Wenzhou University]. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Fei, L., Sun, X., Wei, C., Luo, F., Li, Z., Shen, L., Xue, G., & Lin, X. (2018). Parental rearing behaviors and adolescent’s social trust: Roles of adolescent self-esteem and class justice climate. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(5), 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. (2005). Risk: A sociological theory. Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lyun, M. R. (1986). Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing Research, 35(6), 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. (2001). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for Windows (versions 10–11). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, P. (1999). Is social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. American Journal of Sociology, 105(1), 88–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2006). The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(5), 489–497. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, C. L., Linley, P. A., & Maltby, J. (2009). Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(5), 583–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (2001). Social capital: Measurement and consequences. Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2(1), 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H. (2010). Quantitative research and statistical analysis: Examples of SPSS data analysis. Chongqing University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel, J. K., & Holmes, J. G. (1986). How do I trust thee? Psychology Today, 20(2), 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter, J. B. (1967). A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. Journal of Personality, 35(4), 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J. B. (1971). Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trust. American Psychologist, 26, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statman, M. (2015). Culture in risk, regret, maximization, social trust, and life satisfaction. Journal of Investment Consulting, 16(1), 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter, M., & Kocher, M. G. (2007). Trust and trustworthiness across different age groups. Games and Economic Behavior, 59(2), 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielmann, I., & Hilbig, B. E. (2015). Trust: An integrative review from a person–situation perspective. Review of General Psychology, 19(3), 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslaner, E. M. (2003). Varieties of trust. European Political Science, 2(1), 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, P., Thompson, J. K., Obremski-Brandon, K., & Coovert, M. (2002). The tripartite influence model of body image and eating disturbance: A covariance structure modeling investigation testing the mediational role of appearance comparison. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(5), 1007–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3(1), 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Li, Q., Zhang, S., Wei, Y., & Jian, W. (2024). Urban-rural disparities in the association between social trust patterns and changes in depressive symptoms: Longitudinal evidence from an elderly Chinese population. BMJ Open, 14(12), e086508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray-Lake, L., & Flanagan, C. A. (2012). Parenting practices and the development of adolescents’ social trust. Journal of Adolescence, 35(3), 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. (2010). Questionnaire statistical analysis practice: SPSS operation and application. Chongqing University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. (2020). Structural equation modeling: AMOS practical advancement. Chongqing University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, C., Yao, Y., Hu, T., Cheng, J., Xu, S., & Liu, C. (2023). The role of subjective well-being in mediating social trust to the mental health of health workers. Healthcare, 11(9), 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Zhang, C., & Huang, Y. (2023). Social trust, social capital, and subjective well-being of rural residents: Micro-empirical evidence based on the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS). Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, T., Akutsu, S., Cho, K., Inoue, Y., Li, Y., & Matsumoto, Y. (2015). Two-component model of general trust: Predicting behavioral trust from attitudinal trust. Social Cognition, 33(5), 436–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, T., & Yamagishi, M. (1994). Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motivation and Emotion, 18(2), 129–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. J. (2020). Social trust and satisfaction with life: A cross-lagged panel analysis based on representative samples from 18 societies. Social Science & Medicine, 251, 112901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M., Li, Y., Lin, J., Fang, Y., Yang, Y., Li, B., & Dong, Y. (2024). The relationship between trust and well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 25(5), 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | t | Cohen’s d | r | Item | t | Cohen’s d | r | Item | t | Cohen’s d | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST1 | −16.15 *** | −1.36 | 0.49 ** | ST14 | −23.41 *** | −1.97 | 0.63 ** | ST27 | −24.23 *** | −2.04 | 0.69 ** |

| ST2 | −19.77 *** | −1.66 | 0.59 ** | ST15 | −27.16 *** | −2.28 | 0.72 ** | ST28 | −25.29 *** | −2.13 | 0.68 ** |

| ST3 | −14.36 *** | −1.21 | 0.49 ** | ST16 | −18.90 *** | −1.59 | 0.53 ** | ST29 | −0.26 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| ST4 | −16.58 *** | −1.39 | 0.50 ** | ST17 | −24.56 *** | −2.07 | 0.67 ** | ST30 | −22.36 *** | −1.88 | 0.63 ** |

| ST5 | −19.54 *** | −1.64 | 0.60 ** | ST18 | −2.13 * | −0.18 | 0.08 ** | ST31 | −29.35 *** | −2.47 | 0.72 ** |

| ST6 | −16.42 *** | −1.38 | 0.53 ** | ST19 | −25.33 *** | −2.13 | 0.69 ** | ST32 | −25.39 *** | −2.14 | 0.68 ** |

| ST7 | −21.93 *** | −1.84 | 0.65 ** | ST20 | −24.50 *** | −2.06 | 0.68 ** | ST33 | −24.11 *** | −2.03 | 0.71 ** |

| ST8 | −21.06 *** | −1.77 | 0.60 ** | ST21 | −18.05 *** | −1.52 | 0.58 ** | ST34 | −22.72 *** | −1.91 | 0.67 ** |

| ST9 | −18.93 *** | −1.59 | 0.61 ** | ST22 | −20.35 *** | −1.71 | 0.63 ** | ST35 | −24.40 *** | −2.05 | 0.67 ** |

| ST10 | −18.48 *** | −1.55 | 0.59 ** | ST23 | −1.18 | −0.10 | 0.07 * | ST36 | −22.85 *** | −1.92 | 0.64 ** |

| ST11 | −21.12 *** | −1.78 | 0.63 ** | ST24 | −20.38 *** | −1.71 | 0.62 ** | ST37 | −21.82 *** | −1.83 | 0.67 ** |

| ST12 | −24.49 *** | −2.06 | 0.68 ** | ST25 | −25.86 *** | −2.17 | 0.69 ** | ||||

| ST13 | −20.73 *** | −1.74 | 0.65 ** | ST26 | −9.37 *** | −0.79 | 0.33 ** |

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Commonalities | Item | Factor 4 | Commonalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST4 | 0.883 | 0.621 | ST15 | 0.882 | 0.670 | ||

| ST16 | 0.652 | 0.475 | ST27 | 0.828 | 0.617 | ||

| ST1 | 0.623 | 0.437 | ST32 | 0.797 | 0.576 | ||

| ST24 | 0.409 | 0.443 | ST25 | 0.802 | 0.555 | ||

| ST37 | 0.378 | 0.483 | ST31 | 0.753 | 0.601 | ||

| ST14 | 0.816 | 0.631 | ST17 | 0.702 | 0.534 | ||

| ST2 | 0.734 | 0.545 | ST19 | 0.698 | 0.529 | ||

| ST5 | 0.723 | 0.577 | ST28 | 0.698 | 0.523 | ||

| ST20 | 0.684 | 0.601 | ST11 | 0.691 | 0.471 | ||

| ST36 | 0.599 | 0.530 | ST33 | 0.665 | 0.513 | ||

| ST9 | 0.881 | 0.679 | ST12 | 0.619 | 0.480 | ||

| ST3 | 0.742 | 0.487 | ST8 | 0.575 | 0.383 | ||

| ST10 | 0.731 | 0.539 | |||||

| ST22 | 0.701 | 0.566 | |||||

| ST21 | 0.641 | 0.494 | |||||

| Eigenvalues (after rotation) | 1.243 | 1.617 | 2.399 | 11.091 | |||

| Explained variance (%) | 4.604 | 5.989 | 8.886 | 41.077 | |||

| Cumulative variance contribution rate (%) | 4.604 | 10.593 | 19.479 | 60.555 |

| Item | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 1319.744 *** | 320 | 4.124 | 0.055 | 0.906 | 0.897 | 0.046 |

| Three-factor model | 1664.127 *** | 321 | 5.184 | 0.064 | 0.874 | 0.862 | 0.054 |

| Two-factor model | 2159.303 *** | 323 | 6.685 | 0.075 | 0.828 | 0.813 | 0.060 |

| One-factor model | 3340.230 *** | 324 | 10.309 | 0.096 | 0.717 | 0.694 | 0.084 |

| Variables | M ± SD | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s Omega | Test–Retest Reliability | Correlation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Trust | Trust Propensity | Life Satisfaction | |||||

| Social trust | 94.506 ± 14.846 | 0.931 | 0.931 | 0.927 | 0.209 ** | 0.472 ** | 0.455 ** |

| Trust in relatives | 18.870 ± 3.281 | 0.758 | 0.759 | 0.894 | 0.197 ** | 0.375 ** | 0.451 ** |

| Trust in friends | 16.961 ± 3.426 | 0.814 | 0.815 | 0.918 | 0.172 ** | 0.388 ** | 0.320 ** |

| Trust in strangers | 15.632 ± 3.069 | 0.743 | 0.757 | 0.862 | 0.175 ** | 0.463 ** | 0.286 ** |

| Trust in the organization | 43.071 ± 7.917 | 0.904 | 0.905 | 0.916 | 0.158 ** | 0.381 ** | 0.419 ** |

| Model | χ2/df | RMSEA [90% CI] | CFI | TLI | SRMR | ΔCFI | ΔTLI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (nmale = 634, nfemale = 580) | ||||||||

| Configural | 1730.867 ***/634 | 0.055 [0.052; 0.059] | 0.879 | 0.867 | 0.048 | - | - | - |

| Partial Configural | 1478.136 ***/669 | 0.046 [0.043; 0.050] | 0.911 | 0.907 | 0.048 | - | - | - |

| Partial Metric | 1500.866 ***/670 | 0.047 [0.044; 0.050] | 0.909 | 0.904 | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.003 | −0.001 |

| Partial Scalar | 1460.101 ***/667 | 0.046 [0.043; 0.049] | 0.913 | 0.908 | 0.048 | −0.004 | −0.004 | 0.001 |

| Educational stage (njunior high school = 631, nsenior high school = 583) | ||||||||

| Configural | 1735.971 ***/634 | 0.056 [0.052; 0.059] | 0.876 | 0.863 | 0.048 | - | - | - |

| Partial Configural | 1383.651 ***/620 | 0.047 [0.044; 0.050] | 0.914 | 0.903 | 0.045 | - | - | - |

| Partial Metric | 1539.727 ***/664 | 0.048 [0.045; 0.052] | 0.901 | 0.896 | 0.053 | 0.013 | 0.007 | −0.008 |

| Partial Scalar | 1576.054 ***/667 | 0.049 [0.046; 0.052] | 0.898 | 0.892 | 0.059 | 0.003 | 0.004 | −0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Development and Validation of Social Trust Scale for Chinese Adolescents (STS-CA). Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1436. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111436

Bai Y, Li L, Yang Y, Liu Y. Development and Validation of Social Trust Scale for Chinese Adolescents (STS-CA). Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1436. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111436

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Youling, Luoxuan Li, Yuhan Yang, and Yanling Liu. 2025. "Development and Validation of Social Trust Scale for Chinese Adolescents (STS-CA)" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 11: 1436. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111436

APA StyleBai, Y., Li, L., Yang, Y., & Liu, Y. (2025). Development and Validation of Social Trust Scale for Chinese Adolescents (STS-CA). Behavioral Sciences, 15(11), 1436. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15111436