Resilience Through Belonging: Schools’ Role in Promoting the Mental Health and Well-Being of Children and Young People

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Widening the Resilience Lens in Educational Policy

“We have launched this strategy with the aim of forging even stronger bonds across our communities, and creating a stable foundation for future prosperity”.

1.2. Belonging, Well-Being and Identity

“That sense of being somewhere where you can be confident that you will fit in and feel safe in your identity, a feeling of being at home in a place, and of being valued.”

2. Methodology

2.1. Setting

2.2. Measures

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

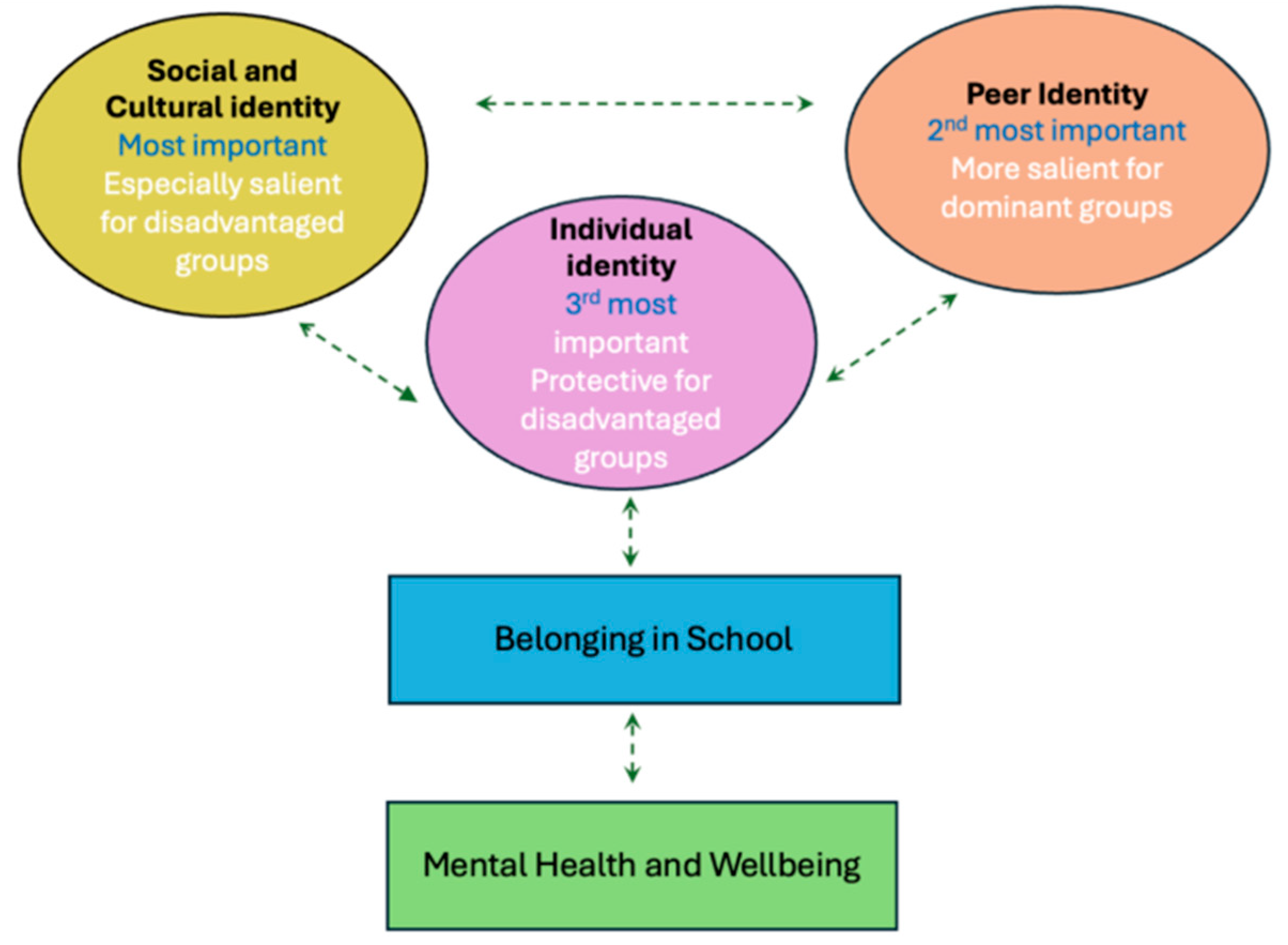

3.1. Data on the Important Factors That Support Students’ Sense of Belonging

3.2. Social and Cultural Identities

3.2.1. Quantitative Evidence from the Online Survey About the Significance of Social and Cultural Identity for Belonging

3.2.2. Qualitative Data on the Significance of Social and Cultural Identity for Belonging

Respect

“You don’t have to like someone in order to respect them, and as long as everyone has respect for everyone, then that positive relationship is there regardless of whether or not you disagree with each other’s opinions.”FT, Student, Alternative Provision A

“So long as you can get through the day with respecting each other and without getting into fights, again you don’t need to have any interactions with them, completely avoidable.”MT, Student, Alternative Provision A

Cultural Awareness

“I feel like there needs to be more like lessons on actually like different cultures and stuff because… I came to the school (from) a catholic school, so there’s only really like one religion and stuff, so I came here not really knowing much…I feel there needs to be more like diversity in the classes and stuff, like even about races, cultures, religions… because a lot of people like, they fear the unknown.”BL, Student, Secondary Mainstream A

“When it comes to black history month… you shouldn’t only focus on it in one month (per year) … if they do it like yearly, consistently, I think that would… utilise diversity and like culture throughout.”CL, Student, Secondary Mainstream A

“there’s quite a toxic culture of like young people being like homophobic or racist or like sexist just because they’re not being taught about it properly… usually most schools just put on like another assembly, that half the kids go off in, so there needs to be a better way of like actually educating kids.”AW, Student, Secondary Mainstream B

Visibility

“Having a more diverse group of students is really nice because, for example, me, when I was younger, everyone around me they used to straighten their hair and then, like now, I’m friends with people who are more, you know, expressive with their culture and their hair so, you know, it just makes me feel more comfortable to do so.”AL Student, Secondary, Mainstream A

“getting along with other students at school… getting along with someone isn’t as important as just having them respect you. Like you don’t have to converse with everyone that you meet. …, you don’t have to be best friends with everyone, you don’t have to talk to everyone. But just in the sense that like if you guys have a disagreement, you can talk it out respectfully and you guys have a respectful conversation. But getting along with other students to me isn’t as important. I just want to feel I’ve got the same rights to be here.”FT, Student, Secondary, Alternative Provision A

3.3. Peer Group Identity

3.3.1. Quantitative Evidence from the Online Survey About the Importance of Peer Group Identity to Belonging

3.3.2. Qualitative Data on the Significance of Peer Identity for Belonging

“I don’t necessarily like coming to school but I think my friends definitely make it better.”JC, Student, Secondary Mainstream C

“Well because let’s say you had no friends at school, you’re not going to want to come to school because you’ve got no one to speak to you. So, friends make school.”JD, Student, Secondary Mainstream D

“School revolves around like friend groups like friendships. Most teachers see it as being grades and like teaching, but most people see it as like another social life.”JC, Student, Secondary Mainstream E

“we seem to have a very big problem with people, a certain dominance over new kids, because they feel like this is their environment and they shouldn’t let other people come in…especially the boys when they come in, they get pressured…like they look at you, assume that you are a threat to their reputation in school.”GT, Student, Alternative Provision A

“I feel like a lot of jokes are made around especially SEN and then people… feel like they should like, ha ha, laugh at it as well.”CL, Student, Secondary Mainstream A

“if you meet someone nice in school they help you fit in in school and like introduce you to their friends as well which creates like, it’s kind of like a protective barrier from all the bad things in school and like they help you in general with your social skills and like becoming friends with other people.”AW Student, Secondary Mainstream B

“I feel like you should just be around people who don’t peer push you…Yes, so you should really build quality friendships.”HC, Student, Secondary Mainstream C

“I feel like all of this chatting about friendship it’s not really that important because let’s be real yeah, let’s be real, like often your friendships at school are fake and like not really your true self because you’re scared to show it.”BT, Student, Secondary Mainstream D

3.4. Individual Identity Aspects of Belonging

3.4.1. Quantitative Evidence from the Online Survey About the Importance of Individual Identity to Belonging

3.4.2. Qualitative Data on the Importance of Individual Identity

“I think sort of the idea of like productive learning in the sense that like everything you do sort of works towards a goal that’s like beneficial, not just for like the school,—with results, -but for you as a person as well.”CW, Student, Secondary Mainstream B

“after school clubs where it builds on your mental and physical strength, for example boxing as I know boxing is one of the things that we do here at (PRU name) and quite a lot of students benefit from that because like it helps them not just physically but mentally as well because it gets them stronger and it teaches them life skills that they’re going to have for a long time…and that really builds someone as a person”NL, Student, Alternative Provision B

“I feel like (my current provision) does it better than most mainstream schools. They help you be who you are rather than what you’re meant to be or what you’re forced to become. I think in that sense, coming to (my current provision) especially made me realise that it’s not a bad place, but a place to start over again. I feel like a lot of time in mainstream we’re on this one path of becoming what we’re forced to be rather than who we are. So, in that sense, loving, they show us how to love ourselves and be who we are rather than what we’re meant to be.”MT, Student, Alternative Provision A

“At school there is always like people who will be judging you for what you are doing… I feel like you’ll never feel that comfort at school.”EC, Student, Secondary Mainstream C (PP/FSM)

“I feel like, if you are able to be yourself at school, that goes into being able to plan for your future because you need to be yourself before planning for the future.”DL, Student, Mainstream A (Muslim)

“If you’re not confident about your future like you’re not going to go anywhere. You need to be self-confident in yourself and what you’re going to do later on in life”NL, Student, Alternative Provision B

“I feel like the school should push for you to love who you are and just be confident with that even if that means you’re by yourself, you should still be happy without friends.”BC, Student, Secondary Mainstream C

“I feel like, once you know who you are as a person and you can be yourself, then other people will like you for who you are.”DL, Student, Secondary Mainstream, A

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmadi, S., Hassani, M., & Ahmadi, F. (2020). Student- and school-level factors related to school belongingness among high school students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alink, K., Denessen, E., Veerman, G., & Severiens, S. (2023). Exploring the concept of school belonging: A study with expert ratings. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2235979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What Schools Need to Know About Fostering School Belonging: A Meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.-A. (2022). Impact of school-based interventions for building school belongingA in adolescence: A systematic review. Educational Psychology Review, 34(1), 229–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.-A., Greenwood, C. J., Berger, E., Patlamazoglou, L., Reupert, A., Wurf, G., May, F., O’Connor, M., Sanson, A., Olsson, C. A., & Letcher, P. (2024). Adolescent school belonging and mental health outcomes in young adulthood: Findings from a multi-wave prospective cohort study. School Mental Health, 16, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. (1996). The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promotion International, 11(1), 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, S., Bagnall, A. M., Corcoran, R., South, J., & Curtis, S. (2020). Being Well Together: Individual Subjective and Community Wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21, 1903–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrick, E., Moss, R. H., McIvor, C., Endacott, C., Crossley, K., Tanveer, Z., Pickett, K. E., McEachan, R. R. C., & Dickerson, J. (2025). Children’s behavioural and emotional wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the Born in Bradford COVID-19 mixed methods longitudinal study. Wellcome Open Research, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M. P., Ormel, J., Verhulst, F. C., & Oldehinkel, A. J. (2010). Peer stressors and gender differences in adolescents’ mental health: The TRAILS study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(5), 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C. A., Walton, G. M., Job, V., & Stephens, N. (2024). The strengths of people in low-SES positions: An identity-reframing intervention improves low-SES students’ achievement over one semester. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 16, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, D. (2024). New strategy for stronger communities. Available online: https://www.publicsectorexecutive.com/articles/new-strategy-stronger-communities (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Blum, R. W. (2005). A case for school connectedness. Educational Leadership, 62(7), 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bollmer, J. M., Milich, R., Harris, M. J., & Maras, M. A. (2005). A Friend in Need: The Role of Friendship Quality as a Protective Factor in Peer Victimization and Bullying: The Role of Friendship Quality as a Protective Factor in Peer Victimization and Bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(6), 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, G. M. (1986). Coping with threatened identities. Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Breakwell, G. M. (1992). Processes of self-evaluation: Efficacy and estrangement. In G. M. Breakwell (Ed.), Social psychology of identity and the self-concept (pp. 35–55). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brezicha, K. F., & Miranda, C. P. (2022). Actions speak louder than words: Examining school practices that support immigrant students’ feelings of belonging. Equity & Excellence in Education, 55(1–2), 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. (2016). ‘Favourite places in school’ for lower-set ‘ability’ pupils: School groupings practices and children’s spatial orientations. Children’s Geographies, 15(4), 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C., & Carr, S. (2019). Education policy and mental weakness: A response to a mental health crisis. Journal of Education Policy, 34(2), 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C., & Dixon, J. (2020). “Push on through”: Children’s perspectives on the narratives of resilience in schools identified for intensive mental health promotion. British Journal of Educational Research, 46(2), 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C., & Donnelly, M. (2021). Theorising social and emotional wellbeing in schools: A framework for analysing educational policy. Journal of Education Policy, 37(4), 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C., Douthwaite, A., Donnelly, M., & Olaniyan, Y. (2024). Inclusion, belonging and safety in London schools: Full report on behalf of London’s violence reduction unit. Available online: https://www.connectedbelonging.co.uk/assets/docs/UoB%20Full%20Report%20Belonging%2C%20identity%20and%20safety%20in%20London%20schools%20%20Final.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Brown, C., Douthwaite, A., Donnelly, M., & Shay, M. (2025). Connected Belonging: A relational and identity- based approach to schools’ role in promoting child wellbeing. British Educational Research Journal, 51, 1927–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C., & Shay, M. (2021). From resilience to wellbeing: Identity-building as an alternative framework for schools’ role in promoting children’s mental health. Review of Education, 9(2), 599–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. (1999). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carnell, B. (2017). Connecting physical university spaces with research-based education strategy. Journal of Learning Spaces, 6(2), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cefai, C., Simões, C., & Caravita, S. (2021). A systemic, whole-school approach to mental health and well-being in schools in the EU. In NESET report. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cemalcilar, Z. (2010). Schools as socialisation contexts: Understanding the impact of school climate factors on students sense of school belonging. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 59(2), 243–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Mental Health. (2020). Mental health inequalities: Factsheet. Available online: https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/mental-health-inequalities-factsheet/ (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Cheryan, S., Plaut, V. C., Davies, P. G., & Steele, C. M. (2009). Ambient belonging: How stereotypical cues impact gender participation in computer science. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss-Ehlers, C. S. (2008). Sociocultural factors, resilience, and coping: Support for a culturally sensitive measure of resilience. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29(3), 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss-Ehlers, C. S., Yang, Y. T. T., & Chen, W. C. J. (2006). Resilience from childhood stressors: The role of cultural resilience, ethnic identity, and gender identity. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 5, 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- Courtois, A., & Donnelly, M. (2024). Racial capitalism and the ordinary extractivism of British elite schools overseas. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 45(3), 432–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias, R., Blake, M., & Cerda, A. (2024). Institutionalizing a culture of inclusion to upend structural invisibility in school settings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(26), e2409561121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crul, M. (2018). Culture, identity, belonging, and school success. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2018(160), 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demie, F. (2019). The experience of Black Caribbean pupils in school exclusion in England. Educational Review, 73(1), 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Health & Department for Education. (2017). Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: A green paper. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/664855/Transforming_children_and_young_people_s_mental_health_provision.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Derlan, C. L., & Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2015). Brief report: Contextual predictors of African American adolescents’ ethnic-racial identity affirmation-belonging and resistance to peer pressure. Journal of Adolescence, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DfE (Department for Education). (2016). Mental health and behaviour in schools: Departmental advice for school staff. Department for Education. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/508847/Mental_Health_and_Behaviour_-_advice_for_Schools_160316.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Dillon, P., Vesala, P., & Suero Montero, C. (2014). Young people’s engagement with their school grounds expressed through colour, symbol and lexical associations: A Finnish–British comparative study. Children’s Geographies, 13(5), 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrellou, E. (2017). Does an inclusive ethos enhance the sense of school belonging and encourage the social relations of young adolescents identified as having social, emotional and mental health difficulties (SEMH) and moderate learning difficulties (MLD)? [Ph.D. thesis, University College London]. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, M., & Brown, C. (2022). “Policy traction” on social and emotional wellbeing: Comparing the education systems of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Comparative Education, 58(4), 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, M., Brown, C., Sandoval Hernandez, A., & Costas Batlle, I. (2020). Developing social and emotional skills: Education policy and practice in the home nations. NESTA. [Google Scholar]

- Due, C., Riggs, D. W., & Augoustinos, M. (2016). Experiences of school belonging for young children with refugee backgrounds. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 33(4), 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S. (2009). Who am I and what am I going to do with my life? Personal and collective identities as motivators of action. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zaatari, W., & Ibrahim, A. (2021). What promotes adolescents’ sense of school belonging? Students and teachers’ convergent and divergent views. Cogent Education, 8(1), 1984628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, D. P., Ryan, M. K., & Begeny, C. T. (2022). Support (and rejection) of meritocracy as a self-enhancement identity strategy: A qualitative study of university students’ perceptions about meritocracy in higher education. European Journal of Social Psychology, 53, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A. J. (2017). Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(2), 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forshaw, E., & Woods, K. (2023). Student participation in the development of whole-school wellbeing strategies: A systematic review of the literature. Pastoral Care in Education, 41(4), 430–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C. (2016). I find that offensive! Biteback Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, S. W., & O’Brien, J. (2017). Social justice through citizenship education: A collective responsibility. Social Studies Research and Practice, 12(1), 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, T. (2022). A critical realist approach to thematic analysis: Producing causal explanations. Journal of Critical Realism, 21(4), 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamsu, S., Donnelly, M., & Harris, R. (2019). The Spatial dynamics of race in the transition to university: Diverse cities and White campuses in U.K. higher education. Population, Space and Place, 25, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, N., & Abdolrezapour, P. (2020). Group composition and learner ability in cooperative learning: A mixed-methods study. Tesl-Ej, 24(2), n2. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and self-identity self and society in the late modern age. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, Á., Jetten, J., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2014). The more prototypical the better? The allure of being seen as one sees oneself. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 17(4), 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haig, B. D., & Evers, C. W. (2015). Realist Inquiry in social science. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Halse, C. (Ed.). (2018). Interrogating belonging for young people in schools. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, L. (2024). Emotionally based school avoidance in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic: Neurodiversity, agency and belonging in school. Education in Science, 14(2), 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, J. V., & Faircloth, B. S. (2005). The role of friendship in adolescents’ sense of school belonging. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2005(107), 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermans, H. J. M., & Kempen, H. J. G. (1998). Moving cultures: The perilous problems of cultural dichotomies in a globalizing society. American Psychologist, 53(10), 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., & White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(4), 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M. J., & Jetten, J. (2004). The individual within the group: Balancing the need to belong with the need to be different. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(3), 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howdle-Lang, S. (2022). Conceptualising child wellbeing: A case study in a Hong Kong private school [Ph.D. thesis, University of Bath]. [Google Scholar]

- Ivankova, N. V., Creswell, J. W., & Stick, S. L. (2006). Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods, 18(1), 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, P. E., Ryan, N., & Pryor, J. (2012). Does social connectedness promote a greater sense of well- being in adolescence over time? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(2), 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddie, N. (1971). Classroom knowledge. In P. Young (Ed.), Knowledge and control. CollierMacmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C. (2013). Mental health as a complete state: How the salutogenic perspective completes the picture. In bridging occupational, organizational and public health: A transdisciplinary approach (pp. 179–192). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, D., Black, L., Panayiotou, M., Humphrey, N., & Demkowicz, O. (2024). The effects of learning- related and peer- related school experiences on adolescent wellbeing: A longitudinal structural equation model. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4779140 (accessed on 12 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Koirikivi, P., Benjamin, S., Hietajärvi, L., Kuusisto, A., & Gearon, L. (2021). Resourcing resilience: Educational considerations for supporting well-being and preventing violent extremism amongst Finnish youth. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 26(1), 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttner, P. (2023). The right to belong in school: A critical, transdisciplinary conceptualization of school belonging. AERA Open, 9, 23328584231183407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G. W., Kochenderfer, B. J., & Coleman, C. C. (1997). Classroom peer acceptance, friendship, and victimization: Distinct relational systems that contribute uniquely to children’s school adjustment? Child Development, 68(6), 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S., & Naama-Ghanayim, E. (2020). Why care about caring? Linking teachers’ caring and sense of meaning at work with students’ self-esteem, well-being, and school engagement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 91, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G., Li, Z., Wu, X., & Zhen, R. (2022). Relations between class competition and primary school students’ academic achievement: Learning anxiety and learning engagement as mediators. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 775213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London’s Violence Reduction Unit. (2024). London’s inclusion charter. Available online: https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/communities-and-social-justice/londons-violence-reduction-unit-vru/londons-inclusion-charter (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Maine, F., Cook, V., & Lähdesmäki, T. (2019). Reconceptualizing cultural literacy as a dialogic practice. London Review of Education, 17(3), 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maine, F., & Vrikki, M. (2021). Dialogue for intercultural understanding placing cultural literacy at the heart of learning. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy, D. (2021). Children’s Right to Belong?—The Psychosocial Impact of Pedagogy and Peer Interaction on Minority Ethnic Children’s Negotiation of Academic and Social Identities in School. Education Sciences, 11(8), 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, K. C., & Syed, M. (2015). The Field of Identity Development Needs an Identity: An Introduction to The Oxford Handbook of Identity Development. In K. C. McLean, & M. Syed (Eds.), The oxford handbook of identity development. Oxford Library of Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, S., Singh, J. A., Garner, L. S., & Benhorin, S. (2004). Taking advantage of opportunities: Community involvement, well-being, and urban youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34(4), 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearns Macdonald, M. (2023). Using a mosaic-based approach to construct children’s understanding of safe space in school. Educational & Child Psychology, 40(3), 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Midgen, T. (2019). ‘School for Everyone’: An exploration of children and young people’s perceptions of belonging. Educational & Child Psychology, 36(2), 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, N. (2016). Nicky Morgan opens character symposium at Floreat school, press release. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/nicky-morgan-opens-character-symposium-at-floreat-school (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Mulrooney, H. M., & Kelly, A. F. (2020). The university campus and a sense of belonging: What do students think? New Directions in the Teaching of Physical Sciences, 15, 3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noddings, N. (1992). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norrish, J. (2015). Positive education: The Geelong Grammar School journey. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norrish, J., Williams, P., & O’Connor, M. (2013). An applied framework for positive education. International Journal of Wellbeing, 3(2), 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD & European Union. (2022). Health at a Glance: Europe 2022: State of Health in the EU Cycle. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofsted. (2019). Press release: Ofsted’s new inspection arrangements to focus on curriculum, behaviour and development. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ofsteds-new-inspection-arrangements-to-focus-on-curriculum-behaviour-and-development (accessed on 14 May 2019).

- Oyserman, D., Fryberg, S. A., & Yoder, N. (2007). Identity-based motivation and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 1011–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, C., Tyler, C., & Lexmond, J. (2014). Character and resilience manifesto. The All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Social Mobility. Available online: http://www.centreforum.org/assets/pubs/character-andresilience.Pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Philip, P., Allen, K., Parker, R., Guo, J., Marsh, H., Basarkod, G., & Dicke, T. (2022). School belonging predicts whether an emerging adults will be not in education, employment or training (NEET) after school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(8), 1881–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A. (2023). Mental health and care-experienced young people: Are our mental health services appealing and accessible? Available online: https://www.acamh.org/blog/mental-health-children-in-care/ (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Phillipson, B., & Streeting, W. (2025, May 16). Children to be taught to show some grit. The Telegraph. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/politics/2025/05/16/children-to-be-taught-to-show-some-grit/?ICID=continue_without_subscribing_reg_first (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Phinney, J. S., & Ong, A. D. (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, D., & Wiliam, D. (1999). “I’ll be a nothing”: Structure and agency and the construction of identity through assessment. British Educational Research Journal, 25(3), 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Lee, W. (2014). Students’ classroom engagement produces longitudinal changes in classroom motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(2), 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, Y., & Schachter, E. P. (2012). High school identity climate and student identity development. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 37(3), 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridge, T., & Millar, J. (2002). Excluding children: Autonomy, friendship and the experience of the care system. Social Policy and Administration, 34(2), 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, K. (2019). Agency and belonging: What transformative actions can schools take to help create a sense of place and belonging? Educational and Child Psychology, 36(4), 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, K. (2022). Compassionate leadership for school belonging. UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, K., Allen, T., & Coates, M. (2020). Place and belonging in school: Why it matters today. Available online: https://theartofpossibilities.org.uk/docs/NewResearch1A.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Rivas-Drake, D., Seaton, E. K., Markstrom, C., Quintana, S., Syed, M., Lee, R. M., Schwartz, S. J., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., French, S., Yip, T., & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85(1), 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P. (2016). Practising positive education: A guide to improve wellbeing literacy in schools. Positive Psychology Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Roffey, S. (2013). Inclusive and exclusive belonging: The impact on individual and community wellbeing. Educational and Child Psychology, 30(1), 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S., & Mantilla-Blanco, P. (2022). Belonging and not belonging: The case of newcomers in diverse US schools. American Journal of Education, 128(4), 617–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A. M. (2000). Peer groups as a context for the socialization of adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and achievement in school. Educational Psychologist, 35(2), 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A new understanding of happiness and well-being—And how to achieve them. Nicholas Brealey. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. E. (2017). One leader’s account: Introduction and history of positive education. In D. Bott, H. Escamilia, S. B. Kaufman, M. L. Kern, C. Krekel, R. Schlicht-Schmälzle, A. Seldon, M. Seligman, & M. White (Eds.), The state of positive education report [Online]. Available online: https://positivitystrategist.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2017-State-of-Positive-Education.pdf.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Sfard, A., & Prusak, A. (2005). Telling identities: In search of an analytic tool for investigating learning as a culturally shaped activity. Educational Researcher, 34(4), 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shean, M., & Mander, D. (2020). Building Emotional Safety for Students in School Environments: Challenges and Opportunities. In R. Midford, G. Nutton, B. Hyndman, & S. Silburn (Eds.), Health and Education Interdependence. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherriff, N. (2007). Peer group cultures and social identity: An integrated approach to understanding masculinities 1. British Educational Research Journal, 33(3), 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silfver, E., Sjöberg, G., & Bagger, A. (2016). An “appropriate” test taker: The everyday classroom during the national testing period in school year three in Sweden. Ethnography and Education, 11(3), 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobitan, T. (2022). Understanding the experiences of school belonging amongst secondary school students with refugee backgrounds (UK). Educational Psychology in Practice, 38(3), 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, H. (2018). Contextual wellbeing: Creating positive schools from the inside out. WiseSolution. [Google Scholar]

- Sulimani-Aidan, Y., & Melkman, E. (2022). School belonging and hope among at-risk youth: The contribution of academic support provided by youths’ social support networks. Child & Family Social Work, 27(4), 700–710. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L., Liu, B., Huang, S., Huebner, E. S., & Du, M. (2021). Self-esteem and academic engagement among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 684520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. (2017). iGen: Why today’s super- connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy—And completely unprepared for adulthood (and what this means for the rest of us). Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- UCL & the Sutton Trust. (2022). COVID social mobility & opportunities study. Wave 1 initial findings–briefing No. 4: Mental health and wellbeing. Available online: https://cosmostudy.uk/publication_pdfs/mental-health-and-wellbeing.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Ullman, J. (2022). Trans/gender-diverse students’ perceptions of positive school climate and teacher concern as factors in school belonging: Results from an Australian national study. Teachers College Record, 124, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, M. K., & Ehrenreich, S. E. (2014). Bullying may be fueled by the desperate need to belong. Theory into practice, 53(4), 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF Innocenti. (2025). Report Card 19: Child well-being in an unpredictable world. UNICEF Innocenti, Global Office of Research and Foresight. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/eca/press-releases/childrens-wellbeing-worlds-wealthiest-countries-took-sharp-turn-worse-wake-covid-19 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Uslu, F., & Gizir, S. (2017). School belonging of adolescents: The role of teacher–student relationships, peer relationships and family involvement. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 17(1), 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, T., & Nishina, A. (2022). Fostering school belonging and students’ well- being through a positive school interethnic climate in diverse high schools. Journal of School Health, 92(4), 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, J., & Louis, K. S. (2023). The politics of belonging and implications for school organization: Autophotographic perspectives on “fitting in” at school. AERA Open, 9, 233285842211397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weare, K. (2010). Mental health and social and emotional learning: Evidence, principles, tensions, balances. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 3, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K. R., & Caldwell, K. (1997). Friendships, peer acceptance, and group membership: Relations to academic achievement in middle school. Child Development, 68(6), 1198–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westminster Education Forum Keynote Seminar. (2017). Character education in England and the future of the national citizen service, draft agenda. Available online: http://www.westminsterforumprojects.co.uk/forums/agenda/character-ed-2017-agenda.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- White, S. (2015). ‘Relational wellbeing: A theoretical and operational approach’ bath papers in international development and wellbeing (no. 43). Centre for Development Studies, University of Bath. [Google Scholar]

- Witten, K., McCreanor, T., & Kearns, R. (2007). The place of schools in parents’ community belonging. New Zealand Geographer, 63(2), 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youdell, D. (2003). Identity traps or how black students fail: The interactions between biographical, sub-cultural, and learner identities. British Journal of Sociology, 24, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey Item “To feel a sense of belonging, how important is…” | Sources |

|---|---|

| Having someone I trust to talk to at school if I have a problem | Midgen (2019); Sulimani-Aidan and Melkman (2022); Uslu and Gizir (2017); Goodenow (1993); Crul (2018) |

| Positive relationships between staff and students | K.-A. Allen (2022); El Zaatari and Ibrahim (2021); Lavy and Naama-Ghanayim (2020); K.-A. Allen et al. (2024); Uslu and Gizir (2017); Sobitan (2022); Ahmadi et al. (2020) |

| Having a say in decisions about the school | Dimitrellou (2017); Riley (2019); Forshaw and Woods (2023) |

| Taking part in activities, clubs, trips and events at school | Midgen (2019); Hamm and Faircloth (2005); Alink et al. (2023); Goodenow (1993); Hamilton (2024) |

| People noticing when I am good at something | Goodenow (1993); Blum (2005) |

| Getting along with other students at school | El Zaatari and Ibrahim (2021); K.-A. Allen (2022); Uslu and Gizir (2017); Cemalcilar (2010) |

| Having a group of friends in school that I trust | Midgen (2019); Cemalcilar (2010); Hamm and Faircloth (2005); Ahmadi et al. (2020) |

| Families/parents/carers feeling welcome to get involved with what goes on in school | El Zaatari and Ibrahim (2021); Midgen (2019); Uslu and Gizir (2017); Riley (2022) |

| People from all backgrounds (e.g., ethnicities, family income levels, sexualities) feeling welcome and heard in school | Ullman (2022); Sobitan (2022); Philip et al. (2022); McGillicuddy (2021); Ahmadi et al. (2020); Crul (2018) |

| Having a space where my friends and I can hang out in school | Mearns Macdonald (2023); Riley (2019); Brown (2016) |

| Seeing different backgrounds (e.g., culture, religions, races, etc.) represented in school displays and celebrations | Brezicha and Miranda (2022); Cheryan et al. (2009); Walls and Louis (2023); Riley (2022); Crul (2018); Mulrooney and Kelly (2020); Carnell (2017); Dillon et al. (2015) |

| Being treated with as much respect as everyone else at school | K.-A. Allen (2022); K. Allen et al. (2018); Alink et al. (2023); Shean and Mander (2020); Goodenow (1993) |

| Talking about important things that are happening in the world (e.g., Climate Change, wars, Black Lives Matter, Me Too) | Kuttner (2023); Russell and Mantilla-Blanco (2022); Halse (2018); Koirikivi et al. (2021); Maine and Vrikki (2021); Fry and O’Brien (2017); Maine et al. (2019) |

| Having the chance to get involved and make a difference in other people’s lives | Halse (2018); Alink et al. (2023); McMahon et al. (2004); Ghanbari and Abdolrezapour (2020); Li et al. (2022); Fry and O’Brien (2017) |

| Category | Variables Collected | Source of Data |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Gender; Sexuality; Faith; | Self-report (survey) |

| Educational needs | Disability/SEND; Neurodivergence/English as an Additional Language (EAL) | Self-report (survey) |

| Care experience | Care experience; Young carer | Self-report (survey) |

| Migration status | Refugee; Asylum seeker; | Self-report (survey) |

| Socio-economic status | Free School Meal eligibility; Pupil Premium | Linked anonymised administrative data (school record) |

| Factor | Whole Cohort Mean | Rated |

|---|---|---|

| Being treated with as much respect as everyone else at school. | 4.26 | 1 |

| Having a friend or group of friends in school that I trust. | 4.25 | 2 |

| People from all backgrounds (e.g., ethnicities, family income levels, sexualities) feeling welcome and heard in school. | 4.01 | 3 |

| Feeling confident to plan for my future. | 3.88 | 4 |

| Getting along with other students at school. | 3.82 | 5 |

| Seeing different backgrounds (e.g., cultures, religions, races, etc.) represented in school displays and celebrations. | 3.76 | 6 |

| Feeling able to be myself at school. | 3.67 | 7 |

| Having a space where my friends and I can hang out in school. | 3.64 | 8 |

| Positive relationships between staff and students. | 3.57 | 9 |

| Having a say in decisions about the school. | 3.48 | 10 |

| Talking about important things that are happening in the world (e.g., Climate Change, wars, Black Lives Matter, Me Too). | 3.48 | 11 |

| Having someone I trust to talk to at school if I have a problem. | 3.36 | 12 |

| People noticing when I am good at something. | 3.34 | 13 |

| Having the chance to get involved and make a difference in other people’s lives. | 3.29 | 14 |

| Taking part in activities, clubs, trips and events at school. | 3.09 | 15 |

| Families/parents/carers feeling welcome to get involved with what goes on in school. | 2.77 | 16 |

| My school having connections to the local community. | 2.63 | 17 |

| Rated | Factor | Identity Aspect |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Being treated with as much respect as everyone else at school. | Social and cultural identity |

| 2 | Having a friend or group of friends in school that I trust. | Peer identity |

| 3 | People from all backgrounds (e.g., ethnicities, family income levels, sexualities) feeling welcome and heard in school. | Social and cultural identity |

| 4 | Feeling confident to plan for my future. | Individual identity |

| 5 | Getting along with other students at school. | Peer identity |

| 6 | Seeing different backgrounds (e.g., cultures, religions, races, etc.) represented in school displays and celebrations. | Social and cultural identity |

| 7 | Feeling able to be myself at school. | Individual identity |

| 8 | Having a space where my friends and I can hang out in school. | Peer identity |

| 9 | Positive relationships between staff and students. | Relationships |

| 10 | Having a say in decisions about the school. | Individual identity |

| Identity Component | Explanation | Link to Belonging |

|---|---|---|

| Social and Cultural Identities | Shaped by wider social structures and cultural contexts such as ethnicity, gender, language, religion and socio-economic background. They provide a sense of belonging to broader communities (including the family) and influence how students are recognised within the school environment. | Belonging is strengthened when schools affirm and value students’ cultural and social identities; it is undermined when these identities are marginalised or rendered invisible. |

| Peer Identities | Formed through friendships, peer groups and classroom dynamics, these identities are central to how children experience acceptance, inclusion or marginalisation. Peer identities often mediate feelings of belonging in day-to-day school life and can buffer or intensify the impact of wider social disadvantage. | Positive peer recognition and supportive friendships foster belonging, whereas exclusion, bullying or peer conflict erode it. |

| Individual Identities | Reflect personal attributes, values, aspirations and self-concept. Individual identity shapes how children interpret their experiences and negotiate between cultural expectations, peer pressures and personal goals, providing a sense of agency and uniqueness within the school setting. | Belonging is enhanced when schools allow space for individual expression and agency, enabling children to feel seen and valued as unique persons. |

| Social Identity Factor | Whole Cohort Mean | Whole Cohort Mean Position | Groups for Whom Factor Was Particularly Important Mean Rating Position 1 | Groups for Whom Factor Was Relatively Less Important Mean Rating Position 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Being treated with as much respect as everyone else in the school” | 4.26 | 1st | Low SES/deprived (4.34) *1st Girls (4.44) *1st Cisgender (4.36) *2nd Christian (4.34) *1st Sikh (4.43) *1st Muslim (4.32) *1st Black/Black British (4.27) *1st Asian/Asian British (4.26) *1st EAL (4.27) *1st Neurodivergent (4.21) *1st | Not deprived (4.25) *2nd Boys (4.08) *2nd Gender minorities (3.74>) Transgender (3.5) *2nd to 4th All other sexual minority identities (3.77>) *2nd Jewish (3.63) Buddhist (3.83) Hindu (4.2) *2nd–3rd No religion (4.23) Atheist (4.18) SEND (3.79) *3rd Refugee (3.5) Asylum seeker (3.36) *2nd In care (3.71) *3rd White (4.27) *2nd |

| “People from all backgrounds feeling welcome and heard in school” | 4.01 | 3rd | Low SES/deprived(4.08) *3rd Girls (4.28) *3rd Cisgender (4.36) *3rd Hindu (4.38) *1st No religion (4.03) *3rd Atheists (4.08) *4th White (4.02) *3rd Asian/Asian British (4.06) *3rd EAL (4.05) *3rd Neurodivergent (3.96) *3rd | Not deprived (4) *3rd Boys (3.75) *5th Transgender (3.5) and all other gender mins (3.74>) *9–11th All sexual minorities (except bi) 3.42>) *7th–10th Black/Black British (3.96) *4th Muslims (3.96) *4th Young carer (3.92) *3rd In care (3.6) *4th SEND (3.44) *5th Refugee (3.31) *6th Asylum seeker (2.97) *7th |

| “Seeing different backgrounds (e.g., cultures, religions, races, etc.) represented in school displays and celebrations” | 3.75 | 6th | Low SES/deprived (3.94) *5th Girls (4.04) *4th Bisexual (3.84) *6th Christian (3.79) *5th Muslim (3.82) *5th Hindu (4.08) *4th Sikh (4) Black/Black Brit (3.88) *5th Asian/Brit Asian (3.86) *5th EAL (3.88) *5th | NOT deprived (3.75) *6th Boys (3.51) *6th All gender mins (3.17>) *7th–11th All other sex mins (3.36>) *6th–9th No religion (3.72) *6th White (3.73) *6th Neurodivergent (3.64) *6th SEND (3.39) *8th Refugee (3.33) *5th Asylum seekers (3.18) *5th In care (3.57) *6th |

| Peer Identity Factor | Whole Cohort Mean | Whole Cohort Mean Position | Groups for Whom Factor was Particularly Important Mean Rating Position 1 | Groups for Whom Factor was Relatively Less Important Mean Rating Position 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Having a friend or group of friends in school that I trust” | 4.25 | 2nd | Not deprived (4.28) *1st White (4.34) *1st Girls (4.36) *2nd Heterosexual (4.28) *1st Cisgender (4.26) *2nd Young carers (4.34) *1st No religion (4.33) Boys (4.19) *1st In care (3.95) *1st Refugee (4.04) *1st Asylum seeker (3.72) *1st SEND (3.97) *1st Atheists (4.23) *1st Jewish (4.16) *1st All sexual minorities (3.98>) *1st All gender minorities (3.88>) (except Transgender) *1st | Asian/Asian British (4.22) *2nd Black/Black British (4.1) *2nd Muslims (4.21) *2nd Neurodivergent (4.21) *2nd |

| “Getting along with other students at school.” | 3.82 | 5th | Low SES/deprived (3.86) *6th Not deprived (3.84) *5th Cisgender (3.83) *5th Heterosexual (3.94) *4th White (3.86) *4th Christian (3.84) *5th Hindu (3.87) *6th No religion (3.87) *4th Young carers (3.85) *4th SEND (4.04) *1st Boys (3.77) *4th Transgender (3.76) *1st Non-binary (3.81) *1st Asylum seeker (3.5) *3rd | In care (3.73) *5th Sexual minorities (3.58>) *2nd–9th Black/Black British (3.73) *6th Asian/Asian British (3.81) *5th Muslim (3.77) *6th Girls (3.92) *6th Not deprived (3.84) *6th |

| “Having a space where me and my friends can hang out in school” | 3.64 | 8th | Low SES/deprived (3.76) *8th Girls (3.75) *8th Cisgender (3.72) *9th Heterosexual (3.79) *6th Bisexual (3.83) *7th White (3.67) *7th Christian (3.73) *7th Hindu (3.8) *8th Boys (3.56) *5th Gay/Lesbian (3.59) *3rd Not deprived (3.64) *7th | All gender minorities (3.28>) *6th–8th EAL (3.62) *8th Neurodivergent (3.6) *8th SEND (3.3) *9th Refugee (3.26) *8th Asylum seekers (2.82) *10th Black/Black British (3.59) *8th No religion (3.54) *9th Atheist (3.58) *8th Muslim (3.63) *8th Sikh (3.47) *9th Buddhist (3.39) *6th Jewish (3.47) *5th |

| Individual Identity Factor | Whole Cohort Mean | Whole Cohort Mean Position | Groups for Whom Factor Was Particularly Important Mean Rating Position 1 | Groups for Whom Factor Was Relatively Less Important Mean Rating Position 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Feeling confident to plan for my future” | 3.88 | 4th | SES Disadvantaged (4.03) *4th Heterosexual (3.91) *5th Black/Black British (4.02) *3rd Asian/Asian British (3.91) *4th Buddhist (4.06) *1st Hindu (4.07) *5th Muslim (4.06) *3rd Christian (3.95) *4th EAL (4) *4th Boys (3.87) *3rd Asylum seeker (3.52) *2nd | Not deprived (3.86) *4th White (3.82) *5th In care (3.63) *4th SEND (3.52) *4th Refugee (3.45)* 4th Neurodivergent (3.72) *5th All gender mins (3.41>) *5th–8th All sexual mins (3.55>) *5th–9th Girls (3.93) *5th |

| “Feeling able to be myself in school” | 3.67 | 7th | SES Disadvantaged (3.86) *7th Girls (3.88) *7th Heterosexual (3.68) *8th Bisexual (3.88) *5th Black/Black British (3.8) *6th Mixed heritage (3.69) *6th Christian (3.73) *7th Muslim (3.68)* 7th Sikh (3.86) *5th Hindu (3.85) *7th Transgender (3.32) *4th Non-binary (3.41) *5th | Not deprived (3.64) *7th/8th Boys (3.49) *8th White (3.65) *8th Young carer (3.62) *9th SEND (3.44) * 6th Refugee (3.12) *9th Asylum seeker (2.74) *12th In care (3.28) *9th Other sexual mins (3.41>) *6th–8th Jewish (3.11) *11th Buddhist (3.33) *10th |

| “Having a say about decisions about the school” | 3.48 | 10th | Low SES/deprived(3.63) *10th Cisgender (3.6) *10th Christian (3.58) *10th Muslim (3.6) *9th Sikh (3.61) *6th Hindu (3.67) *10th Neurodivergent (3.49) *10th EAL (3.56) *10th Transgender (3.35)* 5th Other gender mins (3.18>) *7th/8th Asylum seekers (3.17) *8th In care (3.39) *7th | Not deprived (3.47) *10th Boys (3.43) *10th White (3.41) *12th SEND (3.04) *11th Refugee (3.09) *11th Girls (3.66) *11th |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brown, C.; Douthwaite, A.; Donnelly, M.; Olaniyan, Y.D. Resilience Through Belonging: Schools’ Role in Promoting the Mental Health and Well-Being of Children and Young People. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101421

Brown C, Douthwaite A, Donnelly M, Olaniyan YD. Resilience Through Belonging: Schools’ Role in Promoting the Mental Health and Well-Being of Children and Young People. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101421

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrown, Ceri, Alison Douthwaite, Michael Donnelly, and Yusuf Damilola Olaniyan. 2025. "Resilience Through Belonging: Schools’ Role in Promoting the Mental Health and Well-Being of Children and Young People" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101421

APA StyleBrown, C., Douthwaite, A., Donnelly, M., & Olaniyan, Y. D. (2025). Resilience Through Belonging: Schools’ Role in Promoting the Mental Health and Well-Being of Children and Young People. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1421. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101421