Discrimination of English Vowel Contrasts in Chinese Listeners in Relation to L2-to-L1 Assimilation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Perceptual Assimilation Model-L2

1.2. Assimilation Overlap and L2 Vowel Discrimination

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Stimuli

2.3. Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Assimilation Types

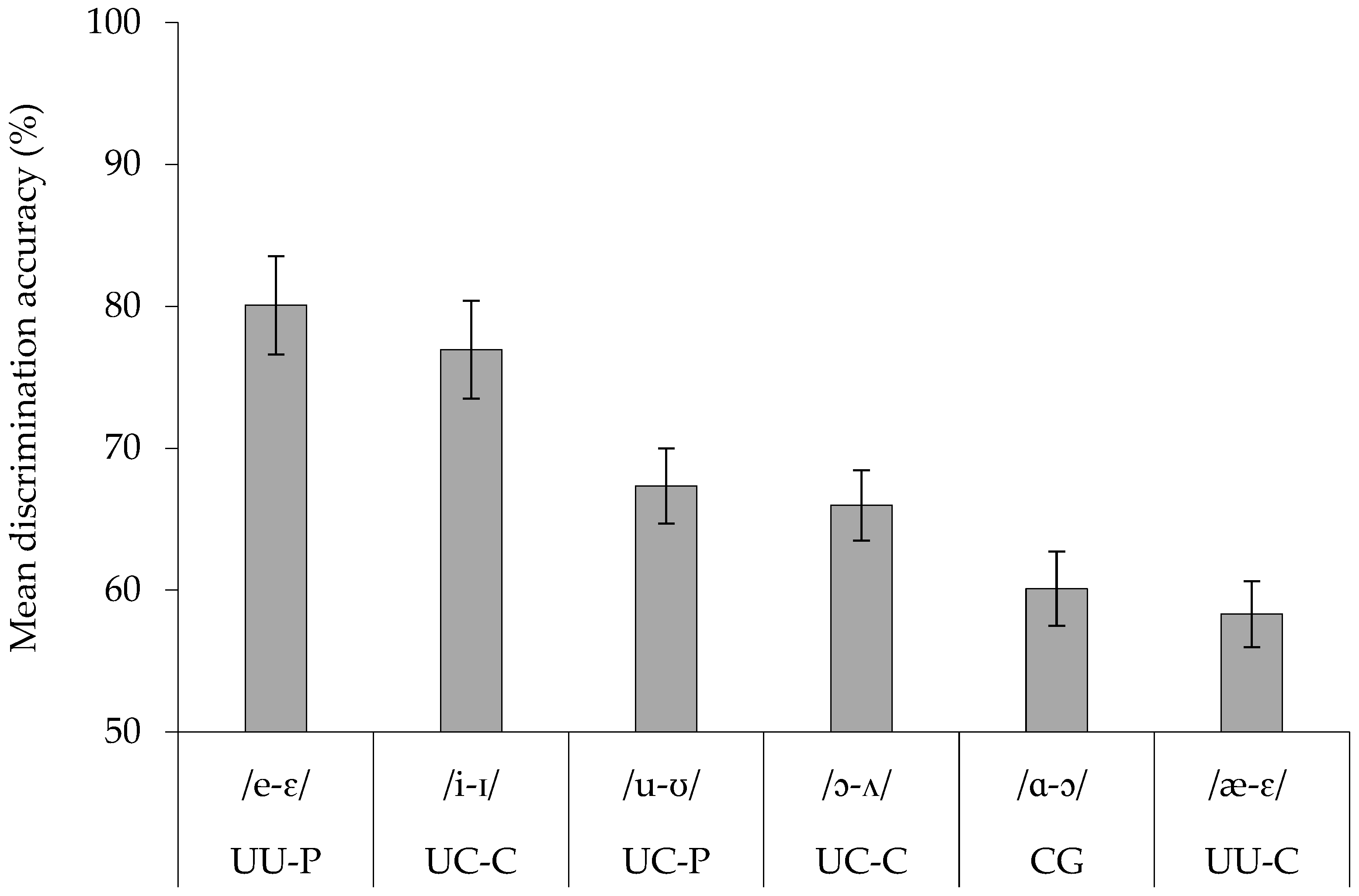

3.2. Dsicrimiantion Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Assimilation Overlap Affects Discriminability of L2 Vowel Contrasts

4.2. Goodness Rating Difference Affect Discriminability of L2 Vowel Contrasts

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baigorri, M., Campanelli, L., & Levy, E. S. (2019). Perception of American–English vowels by early and late Spanish–English bilinguals. Language and Speech, 62(4), 681–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, C. T. (1994). The emergence of native-language phonological influence in infants: A perceptual assimilation model. In J. Goodman, & H. Nusbaum (Eds.), The development of speech perception: The transition from speech sounds to spoken words (pp. 167–224). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Best, C. T. (1995). A direct realist view of cross-language speech perception. In W. Strange (Ed.), Speech perception and linguistic experience: Issues in cross-language research (pp. 171–204). York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Best, C. T., & Tyler, M. D. (2007). Nonnative and second-language speech perception: Commonalities and complementarities. In M. J. Munro, & O.-S. Bohn (Eds.), Language experience in second language speech learning: In honor of James Emil Flege (pp. 13–34). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2021). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version 6.1.40) [software]. Institute of Phonetic Sciences, University of Amsterdam.

- Bundgaard-Nielsen, R. L., Best, C. T., & Tyler, M. D. (2011). Vocabulary size is associated with second-language vowel perception performance in adult learners. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 33(3), 433–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, L. R., & Tyler, M. D. (2023). Predicting discrimination difficulty of Californian English vowel contrasts from L2-to-L1 categorization. Ampersand, 10, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, M. M., Best, C. T., & Tyler, M. D. (2016). An examination of the different ways that non-native phones may be perceptually assimilated as uncategorized. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 139(1), EL1–EL5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faris, M. M., Best, C. T., & Tyler, M. D. (2018). Discrimination of uncategorised non-native vowel contrasts is modulated by perceived overlap with native phonological categories. Journal of Phonetics, 70, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, S. E., Best, C. T., Davis, C., & Tyler, M. D. (2017). The influence of auditory-visual speech and clear speech on cross-language perceptual assimilation. Speech Communication, 92, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flege, J. E. (1995). Second language speech learning: Theory, findings, and problems. Speech perception and linguistic experience. Issues in Cross-Language Research, 92(1), 233–277. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, J. E., & MacKay, I. R. (2004). Perceiving vowels in a second language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26(1), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, G. P. (2022). The acquisition of /ɪ/–/i:/ is challenging: Perceptual and production evidence from Cypriot Greek speakers of English. Behavioral Sciences, 12(12), 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W., Tao, S., Li, M., & Liu, C. (2019). Distinctiveness and assimilation in vowel perception in a second language. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(12), 4534–4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, G., Strange, W., Wu, Y., Collado, J., & Guan, Q. (2006). Perception and production of English vowels by Mandarin speakers: Age-related differences vary with amount of L2 exposure. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 119(2), 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y. H. (2010). English vowel discrimination and assimilation by Chinese-speaking learners of English. Concentric: Studies in Linguistics, 36(2), 157–182. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W. S., & Zee, E. (2003). Standard Chinese (Beijing). Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33(1), 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, E. S. (2009). On the assimilation-discrimination relationship in American English adults’ French vowel learning. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 126(5), 2670–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, Z., Chen, Z., Yang, J., & Xu, L. (2018). Acoustic properties of vowel production in Mandarin-speaking patients with post-stroke dysarthria. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 14188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, Y., Paul, M. J., & Safi, D. (2021). Examination of Korean stop perception in Quebec French listeners through the lens of assimilation overlap. JASA Express Letters, 1(12), 125201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L., & van Heuven, V. J. (2007). Perceptual assimilation of English vowels by Chinese listeners: Can native-language interference be predicted? Linguistics in The Netherlands, 24(1), 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliaferri, B., Turner, C., & James, T. (2010). Paradigm (Version 1.0.2.479) [software]. Perception Research Systems.

- Tyler, M. D., Best, C. T., Faber, A., & Levitt, A. G. (2014). Perceptual assimilation and discrimination of non-native vowel contrasts. Phonetica, 71(1), 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X. (2006). Mandarin listeners’ perception of English vowels: Problems and strategies. Canadian Acoustics, 34(4), 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Bundgaard-Nielsen, R. L., Baker, B. J., & Maxwell, O. (2022, October 20–22). Perceptual overlap in classification of L2 vowels: Australian English vowels perceived by experienced Mandarin listeners. 36th Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation (pp. 317–324), Manila, Philippines. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C. H., & Shih, C. (2009). Mandarin vowels revisited: Evidence from electromagnetic articulography. In Annual meeting of the Berkeley linguistics society (pp. 329–340). University of California. [Google Scholar]

| Chinese Vowels | |||||||

| i | y | ɑ | ɤ | o | u | ||

| English Vowels | i | 91.8 (4.0) 1 | 1.2 (2.3) | 5.9 (4.0) | 0.8 (2.5) | ||

| ɪ | 60.9 (3.1) 2 | 1.2 (3.3) | 8.6 (1.9) | 26.6 (3.2) | 1.2 (3.0) | ||

| e | 45.3 (2.9) | 2.0 (2.6) | 14.5 (1.5) | 37.9 (2.8) | |||

| ɛ | 14.8 (2.3) | 1.2 (2.7) | 48.0 (2.2) | 33.2 (2.7) | 1.6 (3.0) | 1.2 (2.0) | |

| æ | 16.4 (2.0) | 0.8 (2.5) | 44.5 (2.2) | 37.5 (2.6) | 0.4 (3.0) | 0.4 (3.0) | |

| ɑ | 92.6 (4.0) | 1.6 (3.0) | 2.7 (4.0) | 2.0 (3.4) | |||

| ɔ | 0.4 (3.0) | 72.3 (3.6) | 1.6 (3.3) | 24.2 (3.5) | 1.6 (4.0) | ||

| ʌ | 58.2 (3.5) | 23.4 (3.6) | 8.2 (3.3) | 9.4 (3.5) | |||

| ʊ | 24.6 (3.9) | 8.2 (3.7) | 10.9 (3.1) | 55.1 (4.0) | |||

| u | 4.7 (4.1) | 0.4 (4.0) | 6.6 (3.0) | 88.3 (4.2) | |||

| English vowel contrasts | /e-ɛ/ | /i-ɪ/ | /u-ʊ/ | /ɔ-ʌ/ | /ɑ-ɔ/ | /æ-ɛ/ | ||||||

| Categorization status | /e/ | /ɛ/ | /i/ | /ɪ/ | /u/ | /ʊ/ | /ɔ/ | /ʌ/ | /ɑ/ | /ɔ/ | /æ/ | /ɛ/ |

| U | U | C | U | C | U | C | U | C | C | U | U | |

| Native response choices * | /i/ | /ɑ/ | /i/ | /i/ | /u/ | /u/ | /ɑ/ | /ɑ/ | ɑ | ɑ | /ɑ/ | /ɑ/ |

| /ɤ/ | /ɤ/ | /ɑ/ | /ɤ/ | /ɤ/ | ||||||||

| Assimilation type | UU-P | UC-C | UC-P | UC-C | CG | UU-C | ||||||

| Discrimination accuracy (%) | 80.1 | 77.0 | 67.3 | 66.0 | 60.1 | 58.3 | ||||||

| Overall overlap score (%) | 63.7 | 68.8 | 62.1 | 69.5 | 78.1 | 94.1 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nam, Y. Discrimination of English Vowel Contrasts in Chinese Listeners in Relation to L2-to-L1 Assimilation. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101420

Nam Y. Discrimination of English Vowel Contrasts in Chinese Listeners in Relation to L2-to-L1 Assimilation. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101420

Chicago/Turabian StyleNam, Youngja. 2025. "Discrimination of English Vowel Contrasts in Chinese Listeners in Relation to L2-to-L1 Assimilation" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101420

APA StyleNam, Y. (2025). Discrimination of English Vowel Contrasts in Chinese Listeners in Relation to L2-to-L1 Assimilation. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101420