Striving for Career Establishment: Young Adults’ Proactive Development Under Career Identity and Passion Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How does career striving evolve between the pre-graduation career preparation and workforce entrance stages, and then the early years of working?

- During career establishment, what mechanisms determine the trajectories of career striving?

2. Method

2.1. Research Paradigm

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure and In-Depth Interviews

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Multiple Strategies to Enhance Trustworthiness and Interpretative Rigor

3. Results

3.1. Providing Direction for Career Striving: Career Identity Evolving from Career Decisions Made During Higher Education

3.1.1. Theme #1: Career Direction Is Still Being Explored During University and Continues into Early Work Life

3.1.2. Theme #2: Pre-Professional Identity Evolves as University-Acquired Knowledge and Skills Are Applied in the Workplace

You know when I really figured out my teaching philosophy and what kind of teacher I wanted to be?…… It was when I started working! During internships, I was just listening to what teachers said, not really doing much. But once I started working and dealing with different children, it pushed me to develop my own unique abilities. Then, my teaching philosophy was crafting [D2-12-4].

3.1.3. Theme 3: Career Identity Crystallizes Through Compromise Between Ideals and Workplace Reality

3.2. Fueling Career Striving: Passion and Energy Strengthened for Actualizing the Ideal Career During Career Establishment

3.2.1. Theme #4: Career Passion Originates from an Idealized Career Vision During Higher Education

Throughout the journey from university to the present, my goal has always been to get into the tech industry and have the opportunity to work abroad. I wanted to explore the world outside. I was passionately driven to conquer new horizons and blaze a trail beyond the boundaries of my current career! [E5-4-7].

3.2.2. Theme #5: Practical Success Reinforces the Pursuit of Ideal Career Goals

But you know, during the interview process, I didn’t feel like I presented myself in the best way, and that really got me feeling down for a while… However, things took a turn for the better later on. I was fortunate enough to get in touch with the product engineer I admired the most back in high school, and it felt like a stroke of luck! [E5-3-4].

3.2.3. Theme #6: Striving Is Fueled by a Desire to Break Free from Past Limitations

Yeah, back before I graduated, I had this big urge to spice up my life, you know? I didn’t want it to be all too ordinary. Coming from the city and being sheltered by my family, I just felt the need to venture out and connect with different folks from all walks of life. So, I wanted to jump into work early and gather tons of life experiences along the way [D3-7-7].

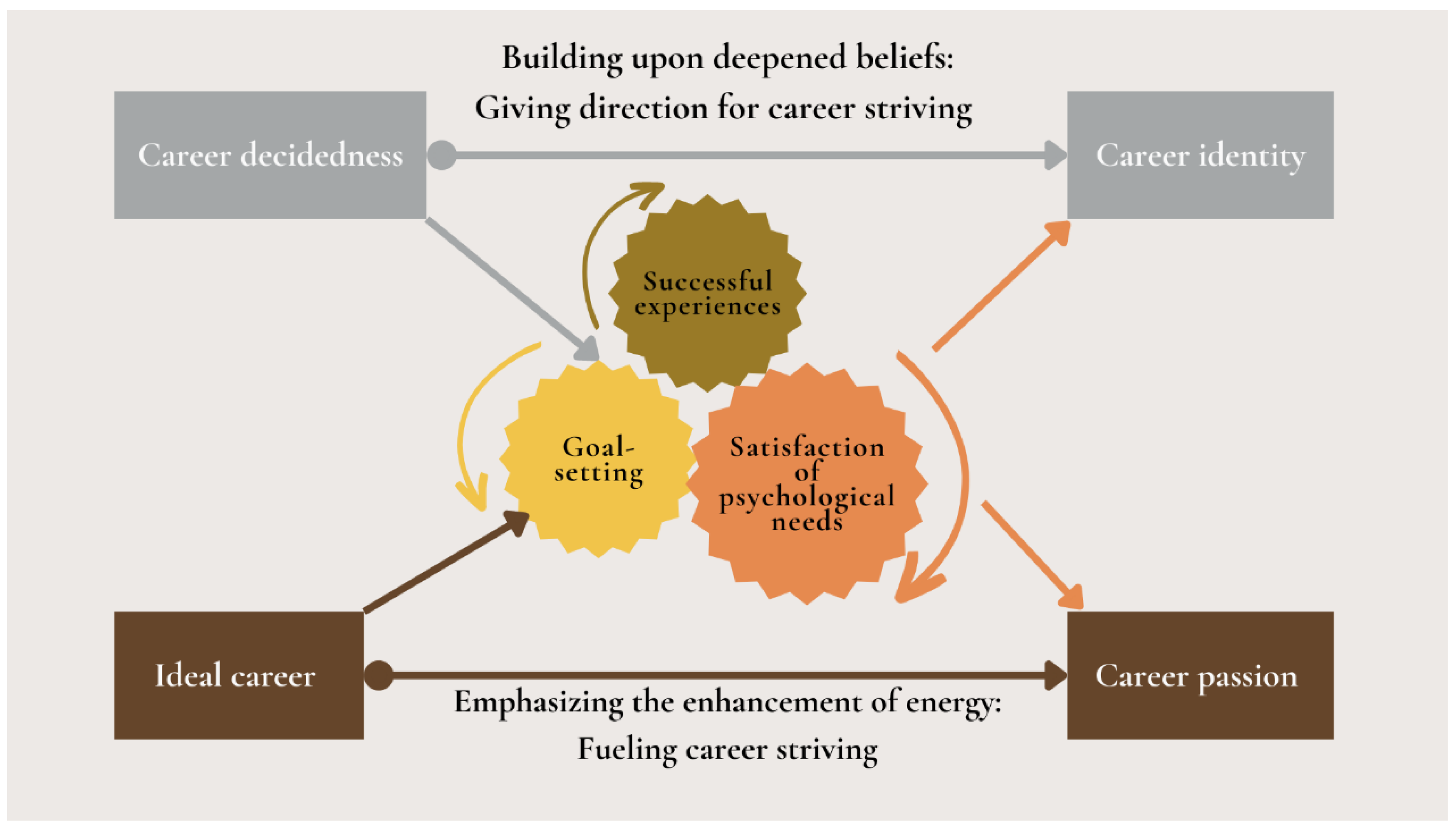

3.3. Career Growth Model: Psychological Mechanisms Promoting Career Striving

3.3.1. Theme #7: Career Striving Is Contingent upon Continuously Recognizing One’s Own Capabilities Through the Successful Experiences of Accomplishing Work Tasks and Career Goals

3.3.2. Theme #8: Continuous Learning and Personal Growth Are Fundamental Aspects of Career Striving

The main thing for me is to improve my abilities in various areas! I want to increase my chances of staying indispensable, so I keep learning and studying. It’s not just about feeling uncertain or threatened; it’s more about wanting more opportunities for myself. I don’t want to be stuck as a primary school teacher forever; I aim to grow and get promoted. Besides, some senior teachers’ attitudes make me want to prove them wrong and show that I have more to offer, regardless of my age or experience. [A4-12-5].

The participants are no longer inexperienced newcomers with limited experience in writing about their past on their resumes [B3]. Both their hard and soft skills are growing rapidly [D4].

3.3.3. Theme #9: Career Striving Solidly Delineates a Differentiated Development Trajectory, with Traces to Follow from Higher Education to Working

I’ll be motivated to do what I want, and I’m ready to put in more time than others to achieve my goals [E5-2-9].

3.3.4. Theme #10: Young Workers Persistently Explore the Actual Work Environment and Seek Better Possibilities for Themselves

If I don’t pass the exam again next year, I might consider changing my environment… Some schools first start with temporary positions and then open official ones, so there’s a chance. I might prefer to go to schools like that [A3-6-4].

3.3.5. Theme #11: Successful Experiences Are Affected by Setting Personal Goals and Engaging in Consistent Practice and Completion, Which Deepen Self-Confidence

Through these goals, I feel that when they trust me, yes, if I gain their trust, they would be willing to communicate with me, and they would be open to making changes together. So, if my influence is recognized, I would feel affirmed… Therefore, in my sense of achievement or successful experiences, I notice something similar, and it boosts my confidence (D5-9-2).

3.3.6. Theme #12: Pursuing Self-Fulfillment and an Increasing Sense of Competence Drive Goal Setting During Transitions

3.3.7. Theme #13: The Desire for Autonomy Arises During the Transition and Drives the Pursuit of Personally Meaningful Goals After Entering the Workplace

It all comes down to doing things I love, having autonomy, feeling happy, and a sense of meaning. The sense of autonomy is more significant than competence, and competence is more important than other factors (B3-10-3).

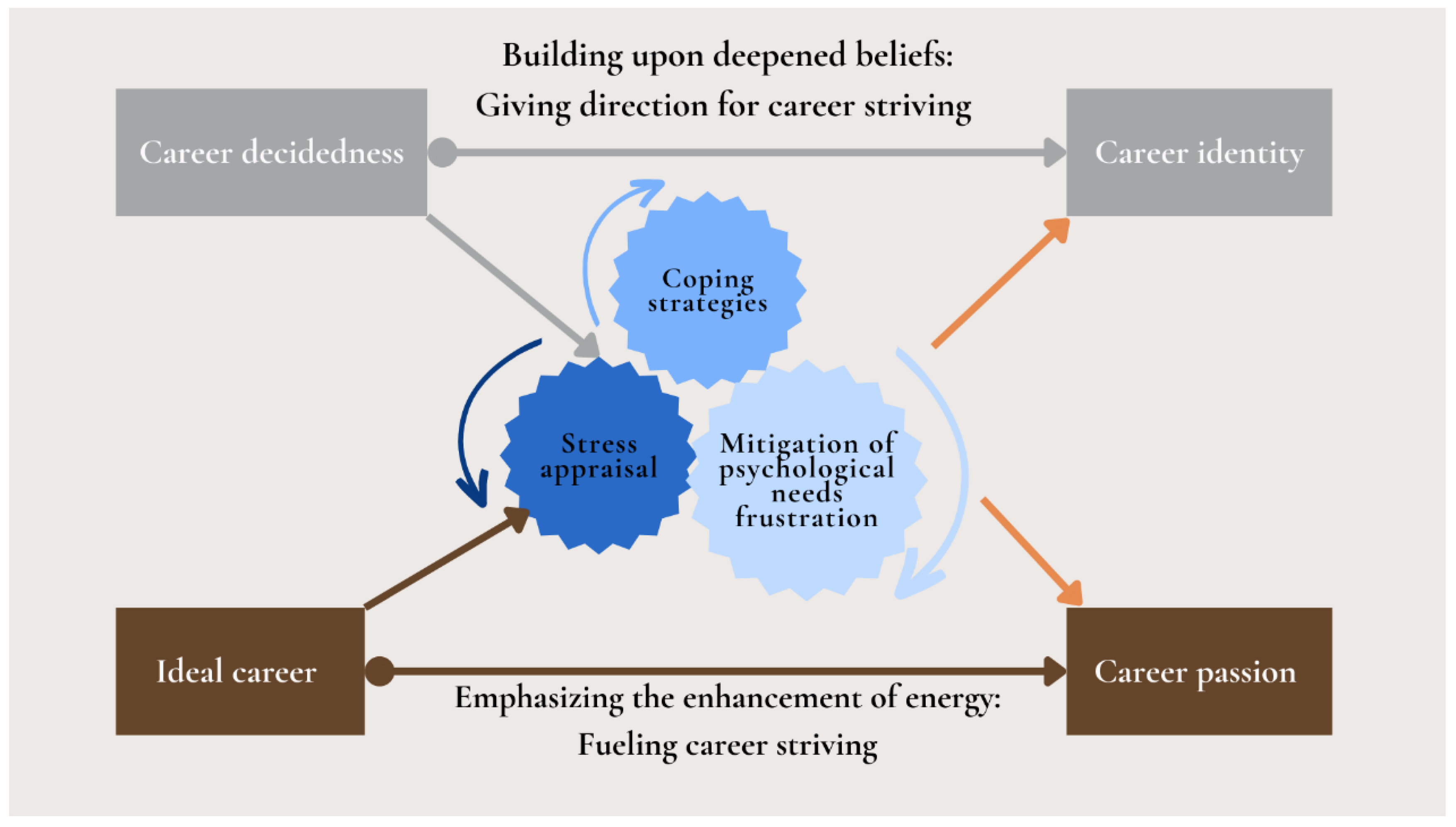

3.4. Stress Coping Model: Psychological Mechanisms When Facing Pressure

3.4.1. Theme #14: Experiencing New Career Insights and Reshaping Beliefs Through Dealing with Pressure and Adaptation

If I don’t achieve my goals, I might doubt my abilities and feel a sense of helplessness and disappointment… I feel that the work environment has a significant influence on who I am now. It provides an outlet for expressing myself, sharing my feelings, and even seeking support [C-2-9].

3.4.2. Theme #15: Developing Flexibility to Balance Ideals and Realities During the Process of Coping with Pressure

Live in the present, enjoy the moment! When something happens, I try to understand and solve it. I used to question my abilities and whether I could do it, but now I just go ahead, give it a try, and then adjust if needed [D4-2-9].

3.4.3. Theme #16: Social Networks Provide Support and Consultation for Coping with Pressure and Problem-Solving

I tend to confide in friends and family when I encounter such difficulties or challenges. It helps me release the pressure and not keep everything bottled up. I used to keep things to myself, but now I can’t bear the feeling of suppressing it. I find comfort in talking to my bandmates. Being listened to is so important [B4-13-2]!

3.4.4. Theme #17: Understanding the Current Situation and Unchangeable Conditions Through Reframing or Gaining Additional Meaningful Perspectives

I imagine myself now as if I am in the fundraising or children’s theater, running a company (this is the participant’s ideal career). There are many things that others haven’t done before, but I am willing to try, and I want to see what the outcome will be. These are all creative processes that others can’t do or haven’t thought of, but for me, it’s about creating something. Oh, this may be related to my future entrepreneurial endeavors. I feel like I am accumulating the necessary experiences for that [A1-14-2].

3.4.5. Theme #18: The Role of a Sense of Competence in Being Motivated to Face Difficulties and Setbacks in Stressful Situations

Throughout my growth process, I firmly believed that I had the ability to overcome challenges. I have confidence in my own capabilities. [A1-7-4]

3.4.6. Theme #19: Persisting Beliefs Derived from Positive Feedback and Confidence Gained Through Overcoming Adversity in Past Growth Experiences

My future is within my grasp, and I refuse to give in… I could have left that environment; many in my class transferred schools, but I felt I didn’t want to, I didn’t want to… It’s like, it’s like feeling a little weak, but I believe I can overcome it all, conquer everything, even the negative forces. Back then, when I was so young, it was this refusal to accept defeat, this belief that I could endure—those thoughts were there long before. (B1-5-4)

3.4.7. Theme #20: Adaptability in Coping Reveals a Psychological Inclination for Career Crafting Through Effective Stress Management

I don’t give up; I try to improve myself and have the belief in creating something new [E5-10-6].

Yeah, I believe it’s not the environment, the world, or society that changes us; we have the opportunity to change it all… I think it’s about daring to pursue what we want… it’s gradually brewing [D5-9-6].

4. Discussion

4.1. Toward the Establishment of Career Striving Theory

4.2. Limitations and Strategies to Address Them

4.3. Future Directions for Exploring the Mechanisms Behind Career Striving

4.3.1. Differentiating the Determinants, Functions, and Consequences of Self-Dialogue and Dialogue with Others in Career Striving

4.3.2. Focusing on Transforming Needs Frustration into Needs Satisfaction

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Guide and Sample Interview Questions

- Pre-graduation career preparation:Can you describe your career goals during your final year of university?How did you prepare for your career while still in higher education?What kinds of proactive steps did you take during university to prepare for your future career (e.g., internships, networking, extra training)?How did you stay motivated or sustain your efforts while managing academic and career-related demands?

- Transition to workforce:What were your experiences transitioning from university to your first full-time job?How did your expectations match the reality of your first job?In what ways did you take initiative or act proactively during the transition to help yourself adjust or succeed in your new role?Were there any steps you took to shape your opportunities or overcome initial challenges when starting work?

- Early career experiences:Can you describe a challenging situation you faced in your first job and how you dealt with it?How have your career goals evolved since you started working?What proactive behaviors have you demonstrated to advance or reshape your career in your current role or workplace?Can you provide an example of a proactive step you took to advance your career?How do you maintain your career motivation or continue striving for long-term goals during this stage?

- Career identity and passion (reflective cross-stage themes)How do you perceive your career identity now compared to when you first graduated?

References

- Ahmed, S. K. (2025). Sample size for saturation in qualitative research: Debates, definitions, and strategies. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 5, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J., & Hirschi, A. (2023). Career proactivity: Conceptual and theoretical reflections. Applied Psychology, 72(1), 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J., & Tims, M. (2017). Crafting your career: How career competencies relate to career success via job crafting. Applied Psychology, 66(1), 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alacovska, A., Fieseler, C., & Wong, S. I. (2021). ‘Thriving instead of surviving’: A capability approach to geographical career transitions in the creative industries. Human Relations, 74(5), 751–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Abadi, H., Coetzer, A., Roxas, H. B., & Pishdar, M. (2023). Informal learning and career identity formation: The mediating role of work engagement. Personnel Review, 52(1), 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auletto, A. (2021). Making sense of early-career teacher support, satisfaction, and commitment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 102, 103321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avargil, S., Saleh, A., & Kerem, N. C. (2025). Exploring aspects of medical students’ professional identity through their reflective expressions. BMC Medical Education, 25(1), 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhate, B., & Dirani, K. M. (2022). Career aspirations of generation Z: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Training and Development, 46(1/2), 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K. (2021). Leaders’ adaptive identity development in uncertain contexts: Implications for executive coaching. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 19(2), 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Blustein, D. L., Lysova, E. I., & Duffy, R. D. (2023). Understanding decent work and meaningful work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branje, S., De Moor, E. L., Spitzer, J., & Becht, A. I. (2021). Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: A decade in review. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 908–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chami-Malaeb, R. (2022). Relationship of perceived supervisor support, self-efficacy and turnover intention, the mediating role of burnout. Personnel Review, 51(3), 1003–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P. C., Guo, Y., Cai, Q., & Guo, H. (2023). Proactive career orientation and subjective career success: A perspective of career construction theory. Behavioral Sciences, 13(6), 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C. P. (1998). Understanding career development: A convergence of perspectives. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 50(3), 437–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coxen, L., van der Vaart, L., Van den Broeck, A., & Rothmann, S. (2021). Basic psychological needs in the work context: A systematic literature review of diary studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 698526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, P., Buys, N., Tilbury, C., & Crawford, M. (2013). The relationship between goal orientation and career striving in young adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(7), 1480–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curşeu, P. L., Semeijn, J. H., & Nikolova, I. (2021). Career challenges in smart cities: A sociotechnical systems view on sustainable careers. Human Relations, 74(5), 656–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, M., Watt, H. M., & Richardson, P. W. (2022). Profiles of teachers’ striving and wellbeing: Evolution and relations with context factors, retention, and professional engagement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(3), 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Corso, J., & Rehfuss, M. C. (2011). The role of narrative in career construction theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B. J., Sargent, A. M., & Steger, M. F. (2008). Career development strivings: Assessing goals and motivation in career decision-making and planning. Journal of Career Development, 35(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, W. E., Baruch, Y., & Ashleigh, M. J. (2020). Striving for sustainable graduate careers: Conceptualization via career ecosystems and the new psychological contract. Career Development International, 25(2), 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, V., & Smith, J. A. (2017). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In C. Willig, & W. Stainton-Rogers (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative psychology (2nd ed., pp. 191–211). Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantinelli, S., Esposito, C., Carlucci, L., Limone, P., & Sulla, F. (2023). The influence of individual and contextual factors on the vocational choices of adolescents and their impact on well-being. Behavioral Sciences, 13(3), 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C., Cai, Y., Yang, Q., Pan, G., Xu, D., & Shi, W. (2023). Career adaptability development in the school-to-work transition. Journal of Career Assessment, 31(3), 476–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X., Gao, L., & Yu, H. (2023). A new construct in career research: Career crafting. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. (1986). The constitution of society. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graça, M., Pais, L., Mónico, L., Santos, N. R. D., Ferraro, T., & Berger, R. (2021). Decent work and work engagement: A profile study with academic personnel. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16(3), 917–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L. M., & Kraimer, M. L. (2020). Goal-setting in the career management process: An identity theory perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(1), 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakvoort, L., Dikken, J., Cramer-Kruit, J., Molendijk-van Nieuwenhuyzen, K., van der Schaaf, M., & Schuurmans, M. (2022). Factors that influence continuing professional development over a nursing career: A scoping review. Nurse Education in Practice, 65, 103481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, N., Sengoku, S., Kubota, Y., Kitahara, S., Lim, Y., & Kodama, K. (2021). Age-dependent influence of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations on construction worker performance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., & Koen, J. (2021). Contemporary career orientations and career self-management: A review and integration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., & Pang, D. (2025). Exploring the “inner compass”: How career strivings relate to career self-management and career success. Applied Psychology, 74(1), e12562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., & Spurk, D. (2021). Striving for success: Towards a refined understanding and measurement of ambition. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 127, 103577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., Zacher, H., & Shockley, K. M. (2022). Whole-life career self-management: A conceptual framework. Journal of Career Development, 49(2), 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V. T., Garg, S., & Rogelberg, S. G. (2021). Passion contagion at work: Investigating formal and informal social influences on work passion. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 131, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holding, A. C., St-Jacques, A., Verner-Filion, J., Kachanoff, F., & Koestner, R. (2020). Sacrifice—But at what price? A longitudinal study of young adults’ sacrifice of basic psychological needs in pursuit of career goals. Motivation and Emotion, 44, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., Lee, J. C. K., & Frenzel, A. C. (2020). Striving to become a better teacher: Linking teacher emotions with informal teacher learning across the teaching career. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, J. L., Smith, J. A., Jesiek, B. K., Zoltowski, C. B., & Oakes, W. C. (2019). Identity in engineering adulthood: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of early-career engineers in the United States as they transition to the workplace. Emerging Adulthood, 7(6), 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaldi, S., Scaratti, G., & Fregnan, E. (2022). Dwelling within the fourth industrial revolution: Organizational learning for new competences, processes and work cultures. Journal of Workplace Learning, 34(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D. (2016). Re-conceptualising graduate employability: The importance of pre-professional identity. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(5), 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L. J., Yap, S., Khei, Z. A. M., Wang, X., Chang, B., Shang, S. X., & Cai, H. (2022). Meaning in stressful experiences and coping across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 53(9), 1015–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z., Jiang, Y., & Nielsen, I. (2021). Thriving and career outcomes: The roles of achievement orientation and resilience. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(1), 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z., Wang, Y., Li, W., Peng, K. Z., & Wu, C. H. (2023). Career proactivity: A bibliometric literature review and a future research agenda. Applied Psychology, 72(1), 144–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, J. M. (2004). Emotion in career contexts: Challenges for theory and research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(3), 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klehe, U. C., Fasbender, U., & van der Horst, A. (2021). sus: Integrating research on career adaptation and proactivity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutscher, G., & Mayrhofer, W. (2023). Mind the Setback! Enacted sensemaking in young workers’ early career transitions. Organization Studies, 44(7), 1127–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langerak, J. B., Koen, J., & van Hooft, E. A. (2022). How to minimize job insecurity: The role of proactive and reactive coping over time. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 136, 103729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lataster, J., Reijnders, J., Janssens, M., Simons, M., Peeters, S., & Jacobs, N. (2022). Basic psychological need satisfaction and well-being across age: A cross-sectional general population study among 1709 Dutch speaking adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(5), 2259–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipscomb, S. T., Chandler, K. D., Abshire, C., Jaramillo, J., & Kothari, B. (2022). Early childhood teachers’ self-efficacy and professional support predict work engagement. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(4), 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, C., Hawlitschek, P., & Deiglmayr, A. (2025). From aspiration to passion–Investigating the role of career choice motivation and self-concept for teacher enthusiasm in early stages of teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 165, 105102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlveen, P., & Luke, J. (2023). Life development and life designing for career construction. In W. B. Walsh, L. Y. Flores, P. J. Hartung, & F. T. L. Leong (Eds.), Career psychology: Models, concepts, and counseling for meaningful employment (pp. 121–142). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, G., Igic, I., Grote, G., & Hirschi, A. (2023). Facing change with stability: The dynamics of occupational career trajectories. Journal of Career Development, 50(4), 883–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, F. (1998). The development of a career identity. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 20, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, F., & Lengelle, R. (2012). Narratives at work: The development of career identity. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 40(2), 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musenze, I. A., Mayende, T. S., Wampande, A. J., Kasango, J., & Emojong, O. R. (2021). Mechanism between perceived organizational support and work engagement: Explanatory role of self-efficacy. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 37(4), 471–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K., Randall, R., Yarker, J., & Brenner, S. O. (2008). The effects of transformational leadership on followers’ perceived work characteristics and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study. Work & Stress, 22(1), 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, P. A., Horberg, E. J., Chen, P., & Savani, K. (2022). Should you pursue your passion as a career? Cultural differences in the emphasis on passion in career decisions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(9), 1475–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsen, A. H., Marescaux, B. P., & Kujanpää, M. (2025). Crafting for autonomy, competence, and relatedness: A self-determination theory model of need crafting at work. Applied Psychology, 74(1), e12570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otu, M. S. (2024). Effect of purpose-based career coaching on career decision-making. Current Psychology, 43(31), 25568–25594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patillon, T. V., Petersen, I. L. L., Moisseron-Baudé, M., Arnoux-Nicolas, C., & Bernaud, J. L. (2025). Adaptation of the meaning of life and meaning of work counseling program in Denmark with youth facing multiple life transitions. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, W. (2019). Career theory for change: The influences of social constructionism and constructivism, and convergence. In J. A. Athanasou, & H. N. Perera (Eds.), International handbook of career guidance (pp. 73–95). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, A. (2025). Enhancing professional identity formation in health professions: A multi-layered framework for educational and reflective practice. Medical Teacher, 47(6), 943–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retkowsky, J., Nijs, S., Akkermans, J., Jansen, P., & Khapova, S. N. (2023). Toward a sustainable career perspective on contingent work: A critical review and a research agenda. Career Development International, 28(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowold, J., & Kauffeld, S. (2008). Effects of career-related continuous learning on competencies. Personnel Review, 38(1), 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L. (2020). Career construction theory and counseling model. In S. Brown, & R. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (3rd ed., pp. 165–200). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I., & Heckhausen, J. (2019). Conceptualizing individual agency in the transition from school to work: A social-ecological developmental perspective. Adolescent Research Review, 4, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, I. (2013). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (4th ed.). Teachers College. [Google Scholar]

- Stremersch, J., Van Hoye, G., & van Hooft, E. (2021). How to successfully manage the school-to-work transition: Integrating job search quality in the social cognitive model of career self-management. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 131, 103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S. E., & Al Ariss, A. (2021). Making sense of different perspectives on career transitions: A review and agenda for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 31(1), 100727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tight, M. (2024). Saturation: An overworked and misunderstood concept? Qualitative Inquiry, 30(7), 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hallen, R., De Pauw, S. S., & Prinzie, P. (2024). Coping,(mal) adaptive personality and identity in young adults: A network analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 36(2), 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hooff, M. L., & van Hooft, E. A. (2023). Dealing with daily boredom at work: Does self-control explain who engages in distractive behaviour or job crafting as a coping mechanism? Work & Stress, 37(2), 248–268. [Google Scholar]

- Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(3), 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tuin, L., Schaufeli, W. B., & Van Rhenen, W. (2020). The satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs in engaging leadership. Journal of Leadership Studies, 14(2), 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., & Li, Y. (2024). Career construction theory: Tools, interventions, and future trends. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1381233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Mei, M., Xie, Y., Zhao, Y., & Yang, F. (2021). Proactive personality as a predictor of career adaptability and career growth potential: A view from conservation of resources theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 699461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendling, E., & Sagas, M. (2024). Career identity statuses derived from the career identity development inventory: A person-centered approach. Psychological Reports, 127(5), 2552–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S. C., & Mohd Rasdi, R. (2019). Influences of career establishment strategies on generation Y’s self-directedness career: Can gender make a difference? European Journal of Training and Development, 43(5/6), 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P., & Chen, C. P. (2024). Advances in social constructionism and its implications for career development. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1485935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S., Shu, D., & Yin, H. (2021). ‘Frustration drives me to grow’: Unraveling EFL teachers’ emotional trajectory interacting with identity development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, W. J. J., & Yang, Y. (2020). Labor market uncertainties for youth and young adults: An international perspective. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 688(1), 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R. A., & Collin, A. (2004). Introduction: Constructivism and social constructionism in the career field. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(3), 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R. A., Valach, L., & Collin, A. (2002). A contextualist explanation of career. In D. Brown, & Associates (Eds.), Career choice and development (4th ed., pp. 206–252). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, D., Kern, M., Tschan, F., Holman, D., & Semmer, N. K. (2021). Emotion work: A work psychology perspective. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8(1), 139–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Wang, X. H., Nerstad, C. G., Ren, H., & Gao, R. (2022). Motivational climates, work passion, and behavioral consequences. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(9), 1579–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Yu, K., Li, W. D., & Zacher, H. (2025). Sustainability of passion for work? Change-related reciprocal relationships between passion and job crafting. Journal of Management, 51(4), 1349–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Career Development Stage | Thematic Dimension | Theme | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: Pre-graduation career preparation | Direction of career striving: Evolving career identity | Theme 1: Career direction is still being explored during university and continues into early work life | Career exploration activities in university support self-understanding, but are insufficient to form a clear, stable career direction at graduation. |

| Motivation for career striving: Emerging career passion | Theme 4: Career passion originates from an idealized career vision during higher education | Passion formed in the university context motivates future vocational pursuits and serves as an early driver of career striving. | |

| Stage 2: Transition into the workforce | Direction of career striving: Evolving career identity | Theme 2: Pre-professional identity evolves as university-acquired knowledge and skills are applied in the workplace | The integration of learned knowledge and early work experience contributes to the development of a vocational self-concept and evolving career identity. |

| Motivation for career striving: Strengthening career passion | Theme 5: Practical success reinforces the pursuit of ideal career goals | Early work achievements boost self-confidence and strengthen motivation to pursue career establishment. | |

| Stage 3: Early career establishment | Direction of career striving: Stabilizing career identity | Theme 3: Career identity crystallizes through compromise between ideals and workplace reality | Young workers develop more functional and realistic career goals by reconciling early aspirations with real-world constraints. |

| Motivation for career striving: Persistent career passion | Theme 6: Striving is fueled by a desire to break free from past limitations | Motivation is reinforced by a need to overcome familial or educational constraints, propelling continued career development and striving. |

| Psychological Mechanisms Promoting Career Striving | Theme | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Self-recognition through accomplishments | Theme 7: Career striving is contingent upon continuously recognizing one’s own capabilities through the successful experiences of accomplishing work tasks and career goals | Successful work experiences affirm young workers’ capabilities and foster a sense of mastery. |

| Drive for learning and development | Theme 8: Continuous learning and personal growth are fundamental aspects of career striving | Young workers exhibit a strong drive for continuous learning and skill development, as essential for career advancement. |

| Developmental trajectory across stages | Theme 9: Career striving solidly delineates a differentiated development trajectory, with traces to follow from higher education to working | Career striving is shaped by workplace experiences that provide opportunities for self-assertion and peer comparison. |

| Exploratory goal orientation | Theme 10: Young workers persistently explore the actual work environment and seek better possibilities for themselves | A proactive exploration of career opportunities helps young workers define their career paths and measures of success. |

| Goal setting and consistency | Theme 11: Successful experiences are affected by setting personal goals and engaging in consistent practice and completion, which deepens self-confidence | Setting and achieving personal goals fosters a cycle of success that builds confidence and reinforces motivation. |

| Pursuit of fulfillment and competence | Theme 12: Pursuing self-fulfillment and an increasing sense of competence drive goal setting during transitions | A sense of competence influences the setting and achievement of personal and professional goals. |

| Autonomy development | Theme 13: The desire for autonomy arises during the transition and drives the pursuit of personally meaningful goals after entering the workplace | The transition to the workforce ignites a desire for autonomy, shaping the pursuit of personal goals. |

| Psychological Mechanisms When Facing Pressure | Theme | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Insight development under pressure | Theme 14: Experiencing new career insights and reshaping beliefs through dealing with pressure and adaptation | Coping with pressure leads to new self-insights and realistic self-concepts. |

| Balancing ideals and reality | Theme 15: Developing flexibility to balance ideals and realities during the process of coping with pressure | Young workers learn to manage between their ideals and workplace realities, enhancing their coping strategies. |

| Social support and consultation | Theme 16: Social networks provide support and consultation for coping with pressure and problem-solving | Social support systems are vital for coping with workplace stress. |

| Cognitive reframing | Theme 17: Understanding the current situation and unchangeable conditions through reframing or gaining additional meaningful perspectives | Reframing challenges as growth opportunities supports career striving. |

| Sense of competence in adversity | Theme 18: The role of a sense of competence in being motivated to face difficulties and setbacks in stressful situations | A strong sense of competence drives proactive behavior in the face of challenges. |

| Confidence from past growth | Theme 19: Persisting beliefs derived from positive feedback and confidence gained through overcoming adversity in past growth experiences | Positive feedback reinforces self-confidence and resilience against adversity. |

| Coping and career crafting | Theme 20: Adaptability in coping reveals a psychological inclination for career crafting through effective stress management | Proactive coping strategies facilitate career crafting and personal fulfillment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, P. Striving for Career Establishment: Young Adults’ Proactive Development Under Career Identity and Passion Dynamics. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1402. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101402

Yang P. Striving for Career Establishment: Young Adults’ Proactive Development Under Career Identity and Passion Dynamics. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1402. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101402

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Peter. 2025. "Striving for Career Establishment: Young Adults’ Proactive Development Under Career Identity and Passion Dynamics" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1402. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101402

APA StyleYang, P. (2025). Striving for Career Establishment: Young Adults’ Proactive Development Under Career Identity and Passion Dynamics. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1402. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101402