Romantic Relationship Quality and Eating Disorder Symptoms in Late Pregnancy: The Serial Mediating Role of Depression and Body Dissatisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

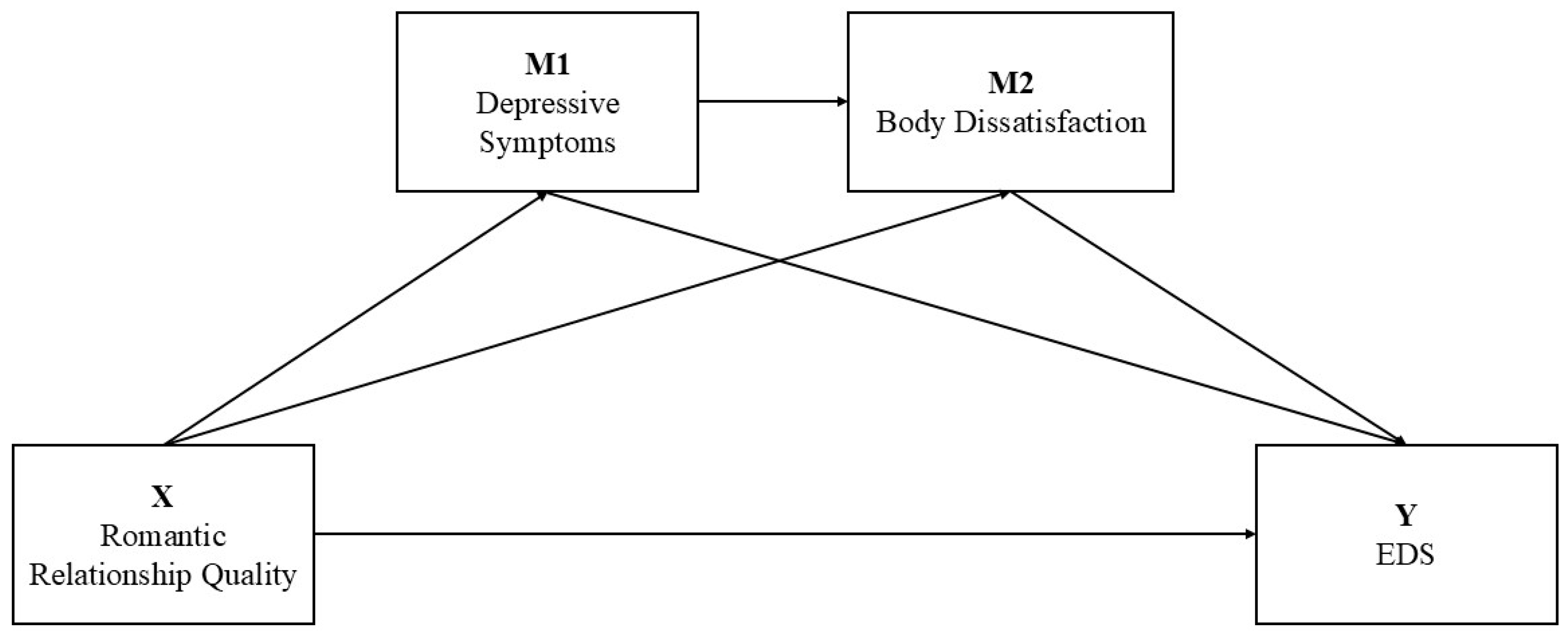

The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dyadic Adjustment Scale 7

2.2.2. Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

2.2.3. Body Image in Pregnancy Scale

2.2.4. Eating Disorder Examination–Questionnaire Short

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Testing for Multicollinearity

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

3.3. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Strengths and Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychological Association. (2010). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychological Association. Available online: http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/principles.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Ansell, E. B., Grilo, C. M., & White, M. A. (2012). Examining the interpersonal model of binge eating and loss of control over eating in women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(1), 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, E., Stamoulou, P., Tzanoulinou, M. D., & Orovou, E. (2021). Perinatal mental health; the role and the effect of the partner: A systematic review. Healthcare, 9(11), 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldoni, F., Giannotti, M., Casu, G., Luperini, V., & Spelzini, F. (2020). A dyadic study on perceived stress and couple adjustment during pregnancy: The mediating role of depressive symptoms. Journal of Family Issues, 41(11), 1935–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannatyne, A. J., Hughes, R., Stapleton, P., Watt, B., & MacKenzie-Shalders, K. (2018). Signs and symptoms of disordered eating in pregnancy: A Delphi consensus study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, R., Galligan, R., & Meyer, D. (2021). Disordered eating from pregnancy to the postpartum period: The role of psychosocial and mental health factors. Appetite, 156, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskin, R., Meyer, D., & Galligan, R. (2020). Psychosocial factors, mental health symptoms, and disordered eating during pregnancy. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(6), 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Başgöl, Ş., Koç, E., & Çankaya, S. (2024). The relationship between postpartum mothers’ dyadic coping and adjustment and psychological well-being. Current Psychology, 43(23), 20668–20676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, P., Ferrara, M., Niccolai, C., Valoriani, V., & Cox, J. L. (1999). The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: Validation for an Italian sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 53(2), 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, G. A. (2023). Beyond BMI. Nutrients, 15(10), 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairo Notari, S., Notari, L., Favez, N., Delaloye, J. F., & Ghisletta, P. (2017). The protective effect of a satisfying romantic relationship on women’s body image after breast cancer: A longitudinal study. Psycho-Oncology, 26(6), 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S., Milanese, C., Sartirana, M., El Ghoch, M., Sartori, F., Geccherle, E., Coppini, A., Franchini, C., & Dalle Grave, R. (2017). The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire: Reliability and validity of the Italian version. Eating and Weight Disorders, 22(3), 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. Y., Lee, A. M., Koh, Y. W., Lam, S. K., Lee, C. P., Leung, K. Y., & Tang, C. S. K. (2020). Associations of body dissatisfaction with anxiety and depression in the pregnancy and postpartum periods: A longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A., Skouteris, H., Wertheim, E. H., Paxton, S. J., & Milgrom, J. (2009). The relationship between depression and body dissatisfaction across pregnancy and the postpartum: A prospective study. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E. C. V., Castanheira, E., Moreira, L., Correia, P., Ribeiro, D., & Graça Pereira, M. (2020). Predictors of emotional distress in pregnant women: The mediating role of relationship intimacy. Journal of Mental Health, 29(2), 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, G., Barberis, N., Cannavò, M., Infurna, M. R., Bevacqua, E., Guarneri, C., Sottile, J., Tomba, E., & Falgares, G. (2025). Exploring the association between childhood emotional maltreatment and eating disorder symptoms during pregnancy: A moderated mediation model with prenatal emotional distress and social support. Nutrients, 17(5), 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, W. R., Barra, J. V., Neves, A. N., Marôco, J., & Campos, J. A. D. B. (2020). Sociocultural pressure: A model of body dissatisfaction for young women. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 36(11), e00059220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, J. C., Bueso-Izquierdo, N., Lara-Cinisomo, S., Lozano-Ruiz, A., & Caparros-Gonzalez, R. A. (2022). Partner relationship quality, social support and maternal stress during pregnancy and the first COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 43(4), 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, P. (2003). Famiglia e capitale sociale nella società italiana. San Paolo Edizioni. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C. G., & Beglin, S. J. (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(4), 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., Broadbent, J., Richardson, B., Watson, B., Klas, A., & Skouteris, H. (2020). A network analysis comparison of central determinants of body dissatisfaction among pregnant and non-pregnant women. Body Image, 32, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, P., Contreras, L., Cassaniti, M., & D’Arista, F. (2002). La Dyadic Adjustment Scale: Una misura dell’adattamento di coppia. Minerva Psichiatrica, 43(2), 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gideon, N., Hawkes, N., Mond, J., Saunders, R., Tchanturia, K., & Serpell, L. (2016). Development and psychometric validation of the EDE-QS, a 12 item short form of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q). PLoS ONE, 11(5), e0152744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, S., Freitas, F., Freitas-Rosa, M. A., & Machado, B. C. (2015). Dysfunctional eating behaviour, psychological well-being and adaptation to pregnancy: A study with women in the third trimester of pregnancy. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(5), 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grano, C., Zagaria, A., Spinoni, M., Solorzano, C. S., Cazzato, V., Kirk, E., & Preston, C. (2025). Body understanding measure for pregnancy scale (BUMPS): Psychometric properties and predictive validity with postpartum anxiety, depression and body appreciation among Italian peripartum women. Body Image, 52, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habarth, J. M., Wickham, R. E., Holmes, K. M., Sandoval, M., & Balsam, K. F. (2019). Heteronormativity and women’s psychosocial functioning in heterosexual and same-sex couples. Psychology & Sexuality, 10(3), 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haynos, A. F., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2011). Anorexia nervosa as a disorder of emotion dysregulation: Evidence and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(3), 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L. M., Oram, S., Galley, H., Trevillion, K., & Feder, G. (2013). Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 10(5), e1001452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunsley, J., Best, M., Lefebvre, M., & Vito, D. (2001). The seven-item short form of the dyadic adjustment scale: Further evidence for construct validity. American Journal of Family Therapy, 29(4), 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir, S. S., Thome, M., Steingrimsdottir, T., Lydsdottir, L. B., Sigurdsson, J. F., Olafsdottir, H., & Swahnberg, K. (2017). Partner relationship, social support and perinatal distress among pregnant Icelandic women. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 30(1), e46–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knoph Berg, C., Torgersen, L., Von Holle, A., Hamer, R. M., Bulik, C. M., & Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. (2011). Factors associated with binge eating disorder in pregnancy. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(2), 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozinszky, Z., & Dudas, R. B. (2015). Validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for the antenatal period. Journal of Affective Disorders, 176, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, K., Lehnig, F., Nagl, M., Stepan, H., & Kersting, A. (2022). Course and prediction of body image dissatisfaction during pregnancy: A prospective study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22(1), 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M. G., Taborelli, E., Easter, A., Bye, A., Eisler, I., Schmidt, U., & Micali, N. (2022). Effect of maternal eating disorders on mother-infant quality of interaction, bonding and child temperament: A longitudinal study. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 31(2), 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Miniati, M., Callari, A., Maglio, A., & Calugi, S. (2018). Interpersonal psychotherapy for eating disorders: Current perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 2018, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, L., Hicks, R. E., & Rosenrauch, S. (2018). Sociocultural pressure as a mediator of eating disorder symptoms in a non-clinical Australian sample. Cogent Psychology, 5(1), 1523347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, P. N., Norona, J. C., Lenger, K. A., & Olmstead, S. B. (2018). How do relationship stability and quality affect wellbeing?: Romantic relationship trajectories, depressive symptoms, and life satisfaction across 30 years. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(7), 2171–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, M., Lampis, J., Murdock, N. L., Schweer-Collins, M. L., & Lyons, E. R. (2020). Couple adjustment and differentiation of self in the United States, Italy, and Spain: A cross-cultural study. Family Process, 59(4), 1552–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røsand, G. M., Slinning, K., Eberhard-Gran, M., Røysamb, E., & Tambs, K. (2011). Partner relationship satisfaction and maternal emotional distress in early pregnancy. BMC Public Health, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortt, J. W., Capaldi, D. M., Kim, H. K., & Laurent, H. K. (2010). The effects of intimate partner violence on relationship satisfaction over time for young at-risk couples: The moderating role of observed negative and positive affect. Partner Abuse, 1(2), 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M. L., Ertel, K. A., Dole, N., & Chasan-Taber, L. (2015). The role of body image in prenatal and postpartum depression: A critical review of the literature. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 18(3), 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J. A., & Rholes, W. S. (2017). Adult attachment, stress, and romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeldt, B., Skårderud, F., Kvalem, I. L., Gulliksen, K. S., & Holte, A. (2022). Bodies out of control: Relapse and worsening of eating disorders in pregnancy. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 986217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa-Gomes, V., Lemos, L., Moreira, D., Ribeiro, F. N., & Fávero, M. (2022). Predictive effect of romantic attachment and difficulties in emotional regulation on the dyadic adjustment. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 20(2), 676–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanier, G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38(1), 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, L. R., Schetter, C. D., Westling, E., Rini, C., Glynn, L. M., Hobel, C. J., & Sandman, C. A. (2012). Perceived partner support in pregnancy predicts lower maternal and infant distress. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(3), 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J., Ellis, A., Roberts, S., Gillespie, K., Bannatyne, A., & Branjerdporn, G. (2024). Disordered eating instruments in the pregnancy cohort: A systematic review update. Eating Disorders, 33(4), 512–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiles, D. L., Ma, L., Fitterman-Harris, H. F., Naseralla, E. J., & Rudolph, C. W. (2022). Body dissatisfaction and romantic relationship quality: A meta-analysis. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 40(6), 1706–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweatt, K., Garvey, W. T., & Martins, C. (2024). Strengths and limitations of BMI in the diagnosis of obesity: What is the path forward? Current Obesity Reports, 13(3), 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderkruik, R., Ellison, K., Kanamori, M., Freeman, M. P., Cohen, L. S., & Stice, E. (2022). Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in the perinatal period: An underrecognized high-risk timeframe and the opportunity to intervene. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 25(4), 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, B., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., Broadbent, J., & Skouteris, H. (2017). Development and validation of a tailored measure of body image for pregnant women. Psychological Assessment, 29(11), 1363–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. (2001). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 79, 373–374. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., Luo, B., Ren, J., Deng, X., & Guo, X. (2023). Marital adjustment and depressive symptoms among Chinese perinatal women: A prospective, longitudinal cross-lagged study. BMJ Open, 13(10), e070234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, S., Gu, W., Zhou, N., Liang, L., Wang, M., Gao, R., Yoong, S. Q., & Wang, W. (2025). Linking self-esteem and marital adjustment among couples in the third trimester of pregnancy: The mediating role of dyadic coping. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 25, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Educational Level | ||

| Middle school diploma | 42 | 18.1 |

| High school diploma | 72 | 31.2 |

| Bachelor’s/Master’s degree | 69 | 29.9 |

| Post-Lauream degree | 48 | 20.8 |

| Work Status | ||

| Housewife/Unemployed | 92 | 39.8 |

| Occasional worker | 27 | 11.7 |

| Employed | 112 | 48.5 |

| Income | ||

| Low | 21 | 9.1 |

| Medium | 144 | 62.3 |

| High | 66 | 28.6 |

| Planned Pregnancy | ||

| Yes | 156 | 67.5 |

| No | 75 | 32.5 |

| Primiparous | ||

| Yes | 139 | 60.2 |

| No | 92 | 39.8 |

| Medically Assisted Procreation | ||

| Yes | 11 | 4.8 |

| No | 220 | 95.2 |

| Pre-Pregnancy Body Mass Index | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 23 | 10.0 |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 131 | 56.7 |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 52 | 22.5 |

| Obesity (>30.0) | 25 | 10.8 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Romantic Relationship Quality | -- | ||||

| 2. Depressive Symptoms | −0.39 ** | -- | |||

| 3. Body Dissatisfaction | −0.33 ** | 0.44 ** | -- | ||

| 4. EDS | −0.18 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.57 ** | -- | |

| 5. Pre-Pregnancy BMI | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.21 ** | 0.23 ** | -- |

| M | 4.23 | 0.55 | 2.29 | 0.52 | 24.13 |

| SD | 0.69 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 5.47 |

| Range | 1.54–5.14 | 0–2.50 | 1.06–4.00 | 0–2.67 | 14.7–45.5 |

| Skewness | −1.10 | 1.14 | 0.42 | 1.14 | 1.41 |

| Kurtosis | 1.71 | 1.13 | 0.06 | 1.22 | 2.66 |

| Outcome | Predictors | R2 | F | β | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive Symptoms | Romantic Relationship Quality | 0.153 | 20.526 | −0.39 | −6.41 | <0.001 | −0.38, −0.20 |

| Pre-Pregnancy BMI | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.842 | −0.01, 0.01 | |||

| Body Dissatisfaction | Romantic Relationship Quality | 0.271 | 28.083 | −0.20 | −3.19 | <0.001 | −0–26, −0.06 |

| Depressive Symptoms | 0.36 | 5.88 | <0.001 | 0.27, 0.54 | |||

| Pre-Pregnancy BMI | 0.22 | 3.91 | <0.001 | 0.01, 0.04 | |||

| EDS | Romantic Relationship Quality | 0.357 | 31.423 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.515 | −0.05, 0.11 |

| Depressive Symptoms | 0.16 | 2.61 | <0.01 | 0.04, 0.27 | |||

| Body Dissatisfaction | 0.48 | 7.75 | <0.001 | 0.31, 0.52 | |||

| Pre-Pregnancy BMI | 0.13 | 2.34 | <0.05 | 0.01, 0.02 |

| Effect | BootSE | Bootstrapping 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | −0.13 | 0.04 | −0.22, −0.05 |

| Direct effect | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.07, 0.11 |

| Indirect effect (X→M1→Y) | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.12, −0.01 |

| Indirect effect (X→M2→Y) | −0.10 | 0.03 | −0.16, −0.03 |

| Indirect effect (X→M1→M2→Y) | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.11, −0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Costanzo, G.; Barberis, N.; Bevacqua, E.; Infurna, M.R.; Falgares, G. Romantic Relationship Quality and Eating Disorder Symptoms in Late Pregnancy: The Serial Mediating Role of Depression and Body Dissatisfaction. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101392

Costanzo G, Barberis N, Bevacqua E, Infurna MR, Falgares G. Romantic Relationship Quality and Eating Disorder Symptoms in Late Pregnancy: The Serial Mediating Role of Depression and Body Dissatisfaction. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101392

Chicago/Turabian StyleCostanzo, Giulia, Nadia Barberis, Eleonora Bevacqua, Maria Rita Infurna, and Giorgio Falgares. 2025. "Romantic Relationship Quality and Eating Disorder Symptoms in Late Pregnancy: The Serial Mediating Role of Depression and Body Dissatisfaction" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 10: 1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101392

APA StyleCostanzo, G., Barberis, N., Bevacqua, E., Infurna, M. R., & Falgares, G. (2025). Romantic Relationship Quality and Eating Disorder Symptoms in Late Pregnancy: The Serial Mediating Role of Depression and Body Dissatisfaction. Behavioral Sciences, 15(10), 1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15101392